“Hokey Pokey” is a perennial wedding reception favorite - “put your left foot in, put your left foot out . . . .”

“Jigaboo” is an archaic insult, a pejorative term for a black person, perhaps a notch or two below the n-word.

What could the two expressions possibly have in common?

Surprisingly, perhaps, forces were set in motion that would influence the history of both expressions on the very same day, May 31, 1830. On that day, two plays debuted in two different theaters

in London. One show called “Hokee Pokee; or, the King of the Cannibal Islands,” staged at the Tottenham Street Theatre, featured a “well known song,” entitled “The King of the Cannibal Islands.”

Another show called “The Progress of a Lawsuit; or, the Travels of a Sailor,” at the Surrey Theatre, featured a copycat song, “All in the Tonga Islands,” the lyrics to which also related to cannibalism

and also included the expression, “Hokey Pokey.”

The two plays and their corresponding songs helped cement “Hokey Pokey’s” place in the language and pop-culture. The original song, “The King of the Cannibal Islands,”

is likely the origin of the expression, “Hokey Pokey.” “Pokey” may be derived from the name of the Governor of Oahau, Hawaii, “Boki,” who famously visited London in 1824 as part of King

Kamehameha II’s entourage. Newspapers frequently spelled his name “Poki.”

The copycat song, “All in the Tonga Islands” (also known as “The Tongo Islands” or “The King of the Tonga Islands”), also helped popularize the expression

“Hokey Pokey” and secure its permanent place in the language and pop-culture. In addition, the song may have influenced (decades later) the song that was the origin of the word “Jigaboo.”

“All in the Tonga Islands” was about a stranded Western sailor who married an island Princess with “rings . . . upon her toes.” Decades later (1909), that plot element

wound up in a song entitled, “I’ve got Rings on My Fingers, or Mumbo Jumbo Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea,” about a stranded Irish sailor named Jim O’Shea, who marries several island women. The sailor’s

island name, “Ji-ji-boo,” was replaced in common usage by “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo,” and changed meaning to become a derogatory term for a black person.i

For more on the history of “Jigaboo” and “Zigaboo,” see my earlier post, “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” - How the Name of a Stranded Irishman Became a Pejorative Term for Black People

- the History and Origins of “Jigaboo.”

As used in the lyrics of the two songs, “Hokey Pokey” was gibberish, intended to evoke the sound of an exotic, unfamiliar island language. But it quickly came to be used as the

name of the fictional King, his island, or minor characters in cannibal-themed plays. It was later used to refer to actual leaders of tropical, Caribbean or Pacific islands. It was also used more generally to refer to any

minor potentate, leader, politician or person in position of power, perceived to be of an inferior quality; anyone who presumed to have more power or prestige than they deserved, or anyone treated with more deference or respect

in their position than they deserved - an inferior, or cheap imitation of a “real” king.

In the immediate aftermath of the debut of the two “Hokey Pokey” songs, the expression was popular enough that it was borrowed for seemingly unrelated purposes; the name of a drink,

a horse race and several different horses. In 1880s California, “Hokey Pokey” emerged as the name of a form of stud poker.

Beginning in the 1870s, “Hokey Pokey” was the name of a frozen dessert sold by street vendors, wrapped in paper, with a rectangular shape - a cheap, inferior imitation of real

ice cream. Some have speculated that frozen “Hokey Pokey” was derived from Italian (“Oh! che poco costa!” - “Oh! how little it costs!”)ii

or from “Hocus Pocus,” ultimately from Latin (“Hoc est corpus meum” - “this is my body”) or mock-Latin (“Hax, Pax, Max Deus Adimax,”iii

an incantation against the bite of a rabid dogiv). But it is possible that using “Hokey Pokey” transferred the sense of being an inferior or phony

imitation from “Hokey Pokey, the King of the Cannibal Islands.”

Similarly, “Hokey Pokey” may have influenced the later use of “hokey,” standing alone, in the sense of “obviously contrived, phony”v

or “obviously fake, phony.”vi I have not found any smoking gun proving the connection (and there are competing explanations), but there is a long

history of using “hokey pokey” in a similar sense and similar contexts, meaning fake, contrived, or phony, suggesting that the notion is at least plausible.

Mr. Wakley now thought that the farce had gone on long enough, and getting rid of Miss O’Key, politely informed Dr. Eliotson of the facts of the case, thereby insinuating that the whole affair was a species of “hokey pokey,” only fit for the court of the King of the Cannibal Islands.”

The Torch, September 8, 1838, page 301.

Zeph Davis didn’t agree with the world at all . . . . “He particularly resented the universal surrender of the race to the spirit of Christmas.

“It’s all hoky poky,” said Zeph.

“Billy’s Christmas” (from the Chicago Times-Herald), Poultney Journal (Poultney, Vermont), December 13, 1895, page 1.

One Senior girl says evolution is a lot of junk. She says what Mr. Darwin wrote is simply full of Hokey Pokey diddle de rum . . . .

The Sedalia Democrat (Sedalia, Missouri), May 23, 1926, page 7.

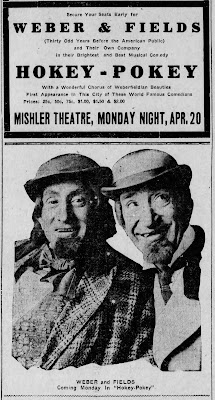

The “Hokey Pokey” dance craze dates to 1942. The earliest references are of British soldiers doing the dance, which was first known as “Cokey Cokey.” It was later

“said to have been introduced [in the United States] . . . by English sailors -- who claimed they picked it up from our own Southern Negroes.”vii

There is some dispute about who wrote the version widely sung today, although a recording of the original British version, “The Cokey Cokey,” by Jimmy Kennedy, sounds suspiciously similar to a recording of the later, American version, “The Hokey Pokey,” by Larry Laprise, who generally gets the lion’s share of the credit. For more on the history of the Hokey Pokey dance craze, see my earlier post, “Hokey Pokey or Hokey Cokey? Wrong! It’s the Cokey Cokey. What’s that all about?”viii

“Hokey” and “Pokey”

As used in “The King of the Cannibal Islands” and “All in the Tonga Islands,” the expression “Hokey Pokey” was gibberish, apparently meant to evoke the

sound of the language spoken on the “Cannibal Island” or the Tonga Islands. Among the gibberish words are other words suggestive of Pacific Islands. “Kaihula” sounds vaguely Hawaiian, and “Tongaree”

suggests an allusion to the Tonga group of islands.

The King of the Cannibal Islands

Hokee pokee wonkee fum,

Puttee po pee kaihula cum,

Tongaree, wongaree, ching ring wum,

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

All in the Tonga Islands (“The Tongo Islands”)

I sailed from Port one summer’s day,

And to the South seas made my way;

I got wrecked in No-bottom bay,ix

All in the Tongo islands.

. . .

Swango, Tongo, hoki poki, hingri chin-gri, soki moki,

Swango, Tongo, hooki pooki,

All in the Tongo Islands.

The two components of “Hokey Pokey” may have been drawn separately from pre-existing words. “By the Hokey” was a common minced oath at the time.

The Catholics of Ireland (no disparagement) are more addicted to this habit than the Protestants, particularly the Presbyterian and Methodistical portion of the community; but a few, even

of the most puritanical of the latter, sometimes indulge, we suppose by way of relief; but, on such occasions, they contrive to evade the laugh of the scorner, by mincing the matter; thus, for “By the hokey!” –

read holy. “By the holy farmer!” - read father, &c. &c.

The Clubs of London, Volume 2, London, Henry Colburn, 1828, page 239.

“Pokey” may have been an allusion to Boki (sometimes spelled “Poki”), the Governor of Oahu and an attendant of King Kamehameha II, who had visited London five years

earlier, in 1825.

Governor Boki and his wife Kuini Liliha (popularly known in the press at the time as “Madame Boki”) visited England a few years earlier, in 1824. They were there as part of the

entourage of the visiting King Kamehameha II, the King of the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii).

|

Boki and Liliha, printed by C. Hullmandel; Drawn on stone from the Original Painting by John Hayter, London, 1824. Wikimedia Commons. |

The King’s name, and those of his attendants, appeared frequently in press accounts of their activities during the stay. When King Kamehameha and his wife tragically died of the measles

during their visit, the names of the highest ranking, surviving members of the delegation, Governor and Madame Boki, appeared even more frequently.

Then, as now, Boki’s name was generally spelled with a “B,” but at that time, it was also frequently spelled with a “P,” even by The Times of London, one of England’s most influential newspapers.

Their Sandwich Majesties. - . . . The King and Queen arrived about 11 o’clock, accompanied by their Prime Minister, Poki, and his wife, and the rest of their suite.

The Times (London), May 31, 1824, page 2.

The London Morning Post editorial position favored the “B,” and they even took it upon themselves to police the correct

spelling of the name.

The Late KING of the SANDWICH ISLANDS.

The leaden coffin containing the remains of his Majesty, was last night placed in the splendid case that has been furnished by Mr. Jarvis, in Long Acre. . . .

The Governor Boki (not Poki), the Admiral Kapihe, Madame Boki (who is in a state of convalescence) . . . are in constant attendance.

The Morning Post (London, July 17, 1824, page 3.

The two words together could have been a corruption of hocus pocus, which was known and in common use in 1830. There has been speculation about a connection between the two expressions since at least as early as 1866.

“Hokey-Pokey, interj. a corruption of hocus-pocus.”

The Dictionary of Reduplicated Words in the English Language, London, Asher and Co., 1866.

Hokey pokey seems a slang version of hocus pocus; hocus pocus is nothing less than a parody on the words of Our Lord, in the Vulgate, “Hoc est corpus.” The expression would thus go back

to the Reformation.

The Western Daily Press (Bristol, England), December 28, 1885, page 3.

The connection seems obvious, but there have not been any examples discovered of “Hokey Pokey” used to mean anything akin to hocus pocus immediately before, during or shortly after 1830, so the connection does not appear to have been on the minds of people at the time.

And decades later, there were those who made the connection to Boki (Poki), or at least his home islands.

Sandwich Islands - “Hokey-Pokey’s” Attempt to Sell his Sovereignty to America. - The King of Owhyee [(Hawaii)] and its dependencies - a Potentate long celebrated in a popular British melody - has in these latter times been converted to Christianity; but, spiritual advantages apart, we

imagine that he would be a happier man if his dominions still retained the title the “Cannibal Islands,” and if his name still began with Hokey-Pokey.

“Items from English Papers,” The Daily British Whig (Kingston, Ontario), December 23, 1853, page 2.

And, in any case, the expression “Hanky Panky,” and not “Hokey Pokey,” was used to refer to sleight-of-hand and stage magic during the period in which “Hokey

Pokey” appeared in association with exotic island kings.

Defendants accused of causing a public disturbance by singing too loudly on their way home from a pub were carrying some cups and balls for performing “hanky-panky.”

The constable here produced a wooden doll, some cups and balls, &c., in a very mysterious manner, at the same time eyeing the melodist in a very suspicious manner.

Defendant - Thems the things what we performs with, just a little of the hanky-panky business at public-houses.

The Times (London), August 23, 1834, page 3.

In an imagined hearing on the application for a booth at a county fair, the board questions the dramatists’ use of magic in their productions.

Punch. - You have degraded the drama by the introduction of card-shufflers and thimble-rig impostors.

Russ. - We denies the thimble-rigging in totum, my lud; that was brought out at Stanley’s opposition booth.

Punch. - At least you were a promoter of state conjuring and legerdermain tricks on the stage.

Russ. - Only a little hanky-panky, my lud. The people likes it; they loves to be cheated before their faces. One, two, three - presto - begone. I’ll show your ludship as pretty a trick of putting a piece of money in your eye and taking it out of your elbow, as you ever beheld.

Punch, Volume 1, week ending September 5, 1841, page 88.

Charles Erskine, Twenty Years Before the Mast, Boston, Charles Erskine, 1890, page 152. Erskine circumnavigated the globe with Charles Wilkes during the United States’ Ex-Ex Expedition, 1838 - 1842. Chief Vendovi had killed and reportedly eaten members

of the crew of the American merchant ship, Charles Daggett, of Salem, Massachusetts, a decade earlier.

The “Cannibal Islands”

The “cannibal islands” of the song were fictional, but generally associated with islands of the South Pacific or East Indies. A century earlier, however, the expression had been

commonly used to refer to islands of the Caribbean or West Indies.

CARIBBE Islands, Islands in the West-Indies, called also Cannibal Islands, from the Peoples feeding on human Flesh.

N. Baily, An Universal Etymological English Dictionary, 7th Edition, London, J. J. and P. Knapton, 1735. Caribee Islands.

The Caribbee or Cannibal Islands derive their common name from certain savage people who formerly inhabited them, and were said to eat human flesh, though there is not sufficient reason to believe,

that either those people, or any other, were guilty of that inhuman practice, except on particular and extraordinary occasions.

Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Volume 26, August 1756, page 367.

Decades later, the location of islands referred to as “Cannibal Islands” moved from the West to the East. In 1813, for example, a magazine promoting missionary work distinguished

illiterate “cannibal islands” from Asian countries with written languages.

One would think, from the objections of some, that these translations were thrown away upon cannibal islands, and set up as a spectacle for savages to stare at. The languages of Asia are

written languages. Can there be a language written without being read?

The Panoplist and Missionary Magazine, Volume 9, Number 9, November 1813, page 422.

And in 1830, an of a mutiny aboard the Cyprus, by convicts bound for Australia on the ship, described the intent of the mutineers, at one point, of sailing to the “Cannibal Islands.”x

The islands were in the South Pacific, and were not one of the islands otherwise mentioned in the account - New Zealand, Otaheite (Tahiti), the Friendly Islands (Tonga). Other island groups in the general vicinity included

Fiji and Samoa, but it is impossible to say which islands were intended.

A viral joke published throughout Britain during 1843 (and reappearing in the United States a decade later), suggested that the Marquesas Islands were “Cannibal Islands.”

Flattering Preference.

Two natives of the Marquesas (Cannibal) islands have been carried to France. The story runs, that on the voyage one of their fellow passengers asked which they liked best, the French or

the English?

“The English,” answered the man, smacking his lips, “they are the fattest.”

Cambridge Independent Press, August 26, 1843, page 2; The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin, Ireland), August 26, 1843, page 1 (and

many others); Washington Telegraph (Washington, Arkansas), October 27, 1852, page 1.

Herman Melville characterized the Marquesas as “Cannibal Islands” in Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life During a Four Months’ Residence in a Valley of the Marquesas

(1846), his most popular book during his lifetime. In one scene, he depicted a shipboard reception of the King and Queen of the Marquesas in which, “the marine guard presented arms, while the band struck up ‘The

King of the Cannibal Islands.’” In another, he offers criticism of the diplomatic recognition of the King of Hawaii, and wonders why other, similarly situated island potentates, should not be granted the same

honor.

Now, if the farcical puppet of a chief magistrate in the Sandwich Islands be allowed the title of King, why should it be withheld from the noble savage Mehevi, who is a thousand times more

worthy of the appellation? All hail, therefore, Mehevi, King of the Cannibal Valley, and long life and prosperity to his Typeean majesty!

Typee, Chapter 26.

After the song became popular in the early 1830s, it became common to make comic allusions to the “Cannibal Islands” and/or “Hokey Pokey” whenever any island small

island nation or its leader was mentioned in the news.

“Hokey Pokey”

On Monday, May 31, 1830, “The King of the Cannibal Islands” was featured in a “burlesque” called, “Hokee Pokee; or, The King of the Cannibal Islands,” at

the Tottenham-Street Theatre (sometimes referred to as the West London Theatre)xi, London. On the same night, a second cannibal-themed song, “All in the

Tonga Islands,” had its premier in a play entitled, “The Progress of a Lawsuit; or, the Travels of a Sailor,” at the Surrey Theatre in St. George’s Fields, Londonxii;

a performer named T. P. Cooke, known for his portrayal of nautical characters, sang the song.

The lyrics of both songs featured the expression, “Hokey Pokey,” and reviews of the two shows are the earliest references to the expression in print.

A new operatic extravaganza, by Mr. Freeman, called Hokee Pokee, or the King of the Cannibal Islands, founded upon the well known song of that name, is to be produced at the Tottenham-street Theatre this evening.

The Sun (London), May 31, 1830, page 3.

[T]he only song allotted to Mr. Cooke was a silly parody of the vulgar and silly song, ‘The King of the Cannibal Islands,’ called, ‘All in the Tonga Islands,’ and

encumbered with the same ‘Hoki Poki’ chorus of the original.

Morning Advertiser (London), June 1, 1830, page 2.

“The Progress of a Law-Suit” received generally good reviews - “Hokee Pokee,” not so much.

TOTTENHAM-STREET THEATRE.

Last night two new pieces were produced at this theatre, - The Midnight Murder and a burlesque called Hokee Pokee. The former was a melo-drama of some interest, and was favourably received

by the audience. The latter, however, experienced a very different fate, which it certainly deserved. It was completely condemned.

SURREY THEATRE.

Last night, a new piece was presented at this theatre, entitled The Progress of a Law Suit, or the Travels of a Sailor, and was produced for the purpose of . . . to afford that first of histrionic

seamen (T. P. Cooke . . .), an opportunity of displaying his powers in a new nautical character. . . . The story is rather lengthy, and could be compressed with advantage to the piece. It was however well received by a crowded

audience, and gave out for repetition amidst considerable applause.

The Standard (London), June 1, 1830, page 3.

At the Surrey, a dramatic satire upon the lawyers, called “The Progress of a Lawsuit; or, a Story of Real Life,” was produced, and pronounced sufficiently entertaining for temporary

purposes. Tottenham Street exhibited a melodrama of some interest,the nature of which may be judged from its title, “The Midnight Murderer;” a burlesque, called “Hokee Pokee,” followed, at the close of which the audience very unequivocally expressed their hope that it would not be repeated.

The Edinburgh Literary Journal, Number 83, June 12, 1830, page 348.

Little is known of the plot of “Hokee Pokee.” Reviews of the play were short and dismissive, without any detail. But if the play followed the plot told by the lyrics of the song,

the reason it was condemned may have to do with gruesome subject matter. The song, “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” features no fewer than 150 deaths, 100 beheadings, and 50 cannibalized wives. The song, “All

in the Tonga Islands,” on the other hand, features a wedding, merely the threat of cannibalism, and a timely escape. In addition, the protagonist of “Tonga Islands” is a Western sailor, not a cannibal king,

with whom the audience may have more easily related.

The lyrics to “The King of the Cannibal Islands” (or at least the nonsensical refrain), first published in 1830, appear to have been set in stone from the beginning. References

to “Hokey Pokey, Wonkee Fum [(or something similar)]. . . The King of the Cannibal Islands” appear in print regularly beginning in 1830 and continuing through the early 1900s.xiii

The 1830 lyrics tell a darkly comic, cautionary tale of a cannibal king - be careful what you seek, it may haunt you in the end. It all starts out innocently enough.

Oh, have you heard the news of late,

About a mighty king so great,

If you have not, ‘tis in my pate,

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

He was so tall near six feet six,

He had a head like Mister Nick’s,

His palace was like Dirty Dick’s,

‘Twas built of mud for want of bricks,

And his name was Poonoowingkewang,

Flibeedee flobeedee buskeebang;

And a lot of Indians swore they’d hang

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

Hokee pokee wonkee fum,

Puttee po pee kaihula cum,

Tongaree, wongaree, ching ring wum,

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

“The King of the Cannibal Islands,” An Original Comic Song, by A. W. Humphreys. Air - Vulcan’s Cave.xiv

The Apollo, Volume 2, London, H. Arliss, 1830, page 22.xv

The rest of the song soon devolves into cannibalism, revenge, mass murder, beheadings and hauntings - perhaps all of the reasons the play it was featured in was so roundly condemned.

The King has one hundred wives who “soon drove him mad” and “every week he was a dad.” When fifty of his wives “gave up the ghost,” he has them all “roasted

soon, and all demolish’d before noon.” The remaining wives run away, each one with a different chief. The King “sent for all his guards with knives, to put an end to all their lives, the fifty chiefs and

fifty wives.” He had their heads carved off one by one, and “laugh’d to see the fun.” But afterward, they haunt him in his dreams - “Every night when he’s asleep, his headless wives and

chiefs all creep, and roll upon him in a heap.”

In 1835, a stage play based on the lyrics of the song limited the number of rival suitors to “three rebel chiefs,” and the number of the Cannibal King’s wives to one. When

the rebel chiefs attempt to kidnap the wife, the King beheads her, after which a fairy reanimates the headless woman - madcap hilarity ensues.xvi

Curiously, despite the published lyrics consistently relating to the King of the Cannibal Islands and his one-hundred wives, an image accompanying those lyrics (in a song book believed to

have been published in about 1835) illustrate a different story entirely.

The image appears above lyrics of “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” but the scene appears to illustrate the plot of a different song. There are no wives, no Cannibalism, no

beheadings and no nightmares, as in “The King f the Cannibal Islands,” but an apparent engagement of a Western sailor and and island princess, straight out of the plot of “The Progress of a Law-Suit,”

in which the “Sailor was loudly encored in a song about his marriage with a daughter of the King of the Tonga Islands.”xvii

The image seems to depict the plot of the song, “All in the Tonga Islands. An islander, perhaps a King or Chief, joins the hands of a Western sailor with that of a young island woman, perhaps his daughter.xviii The happy couple stand in front of a bamboo

stick, in an apparent allusion to the tradition of jumping over a stick or broom as a means of signifying an informal wedding ceremony.

|

The London Melodist: or, Songster’s Companion, London, Deprose & Co., undated [1835?], page 15. |

“The Tongo Islands”

The play, “The Progress of a Lawsuit, or the Travels of a Sailor,” featured cannibalism humor and a song by a “jolly sailor” about his “marriage

with the daughter of the King of the Tonga Islands.” The complicated plot of the play involves a businessman, his wife, her former lover to whom her husband is indebted to the sum of 1000 lb.

An evil lawyer demands payment of the debt and has the husband thrown in jail, against the wishes of his client (the wife’s ex-lover). The wife’s sister’s secret husband’s riches help set everything

right in the end.

In addition to the various legal, financial and interpersonal relationships that drive the plot, some exotic color was introduced through the character of a “jolly sailor” dressed

in a cloak of a Pacific Islander and telling tall tales about his travels.

The business of the drama is assisted by the humours of a jolly sailor, who has been in all the quarters of the globe, and makes his appearance in a cloak or mat of a New Zealand, or Sandwich

Island, or Tonga Island Chief, and tells, or rather spins, long yarns about his adventures in his travels.

Having found a good listener, he tells him that in Africa they call their National Assemblies palavers, and that the natives of the Sandwich Islands eat human flesh; on which the listener aptly observes, that our national Councils might also be called palavers, and that

he would not like a Sandwich of that kind. These repartees were highly applauded, as they could not fail to be.

. . . The Sailor was loudly encored in a song about his marriage with a daughter of the King of the Tonga Islands. . . .

The Morning Chronicle (London), June 1, 1830, page 3.

A song published in 1836, under the title “The Tongo Islands,” appears to be a version of that song. It includes the expression, “hoki poki,” as mentioned in a contemporary

report of the original play, tells of the marriage of a Western sailor and an island Princess, and the final verse even compares lawyers with cannibals, in keeping with the theme of the original play, “The Progress of

a Lawsuit.”

Tongo Islands.

As sung by Mr. Phillimore, at the Warren Theatre.

I SAILED from Port one summer’s day,

And to the South seas made my way;

I got wrecked in No-bottom bay,

All in the Tongo islands.

The king he made a chief of me,

They called him Ro-ra-ki-ro-kee.

We got as thick as thick could be,

And every night drank strong byshee.

Says he, “Will you be my son-in-law,

Marry the princess Was-ki-taw?”

Says I, “Your majesty hold your jaw,

I will accept of the princess’ paw.”

Swango, Tongo, hoki poki, hingri chingri, soki moki,

Swango, Tongo, hooki pooki,

All in the Tongo Islands.

My bride was fair, you may suppose;

She had a feather through her nose,

And rings she had upon her toes,

All in the Tongo islands.

. . .

For though the lawyers here we dread,

Who eat us up alive, ‘t is said,

Yet there they knock you on the head,

And swallow you, after you are dead.

The New Song Book, Containing a Choice Collection of the Most Popular Songs, Glees, Choruses, Extravaganzas, Hartford, Ezra Strong, 1836, page 18.

The intervening verses describe the bride, their home, and their life on the island; the native chiefs become jealous of him and threaten to eat him; he escapes and returns home, where life

is better, at least in part, because the lawyers eat us alive, instead of after we’re dead.

The same song appears in later song collections with minor differences in most of the verses,xix but without the original

second verse which gives a lengthy description of the Princess bride, or any mention of the “rings on her toes.” In addition, although the 1836 version of the song makes the protagonist an American (when he returns

home, he returns to “Columbia’s ground”), later versions leave the nationality of the sailor indefinite (when he returns home, he returns to his “native ground.”).

The song’s plot, about a marriage between a stranded Western sailor and a South Seas island Princess who had “rings upon her toes,” would be echoed nearly eight decades later,

in a song entitled, “I’ve Got Rings on My Fingers, or Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea.”xx

Hokey Pokey in Pop-Culture

The Song

For many decades, the two songs remained in the repertoire of the English-language stage, and audiences were familiar with their lyrics. The similarity of subject matter between the two songs

(South Seas islands and cannibalism) and overlap of lyrical elements (“Hokey Pokey” and cannibalism) caused some to confuse or conflate the two songs into one in their recollections.xxi

Although the song, “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” was described as “well known” in May of 1830, no references to the song prior to that date have been found.

But within months of the common debut of the two plays, mentions of the title of the song, “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” appear in newspapers and magazines; and before the end of the year, the lyrics and

title appear in printed volumes of comic songs.

A report on the goings-on at a local police court, a reporter contrasts the treatment of singers who sang about certain current events with that of singers of generic popular songs.

Two ballad-singers were last week sent to prison . . . for singing songs alluding to the above disgraceful robbery, although no notice is taken of the itinerant vocalist who collects a mob

in the public-street, by telling his hearers that “his heart is breaking for the love of Alice Grey,” requesting “the gentle Moon to rise,” or reciting the adventures of the “King of the Cannibal Islands.”

The Standard (London), September 6, 1830, page 4 (reprinted in the United States, United States Gazette (Philadelphia), October 22, 1830, page 3).

Six years later, itinerant minstrels were still singing the song on the streets of London.

“Hokee Pokee Whankee Fum, the King of the Cannibal Islands,” struck up some wandering minstrel in the street.

The Comic Magazine, Third Series, London, National Library Office, [1836] page 131.

A music critic in a Scottish literary journal approved of the honest “character and grotesque oddity” of the popular Cannibal song, as compared to the pretentious, “puerile

warbling” of some artists who aspire to higher artistic accomplishments.

[W]e would rather a thousand times listen to “Hokey pokey wonky pong, &c., King of the Cannibal Islands,” in which there is at least some character and grotesque oddity, without any anomalous pretence or purile warbling.

The Edinburgh Literary Journal, Number 102, October 23, 1830, page 250.

Sheet music for the new song was available for purchase before the end of October.

Just published, price 6d., arranged for the Piano-forte,

. . . The King of the Cannibal Islands,’ 6d.; . . . .

Published by Duncombe, at his only Shop in London, 19, Little Queenstreet, Holborn; by Sutherland, Edinburgh; and by Wiseheart, Dublin.

The Observer (London), October 31, 1830, page 1.

The difference between two references to “Hokey Pokey,” in successive volumes of a three-volume collection of songs lyrics published in 1830, apparently illustrates the increased

popularity of the song. In Volume II of The Apollo, “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” said to be sung to the tune of an earlier song, “Vulcan’s

Cave.”xxii In Volume III of The Apollo, the song, “The Wake of Teddy the Tiler”, is said to be sung to the tune of “The King of the Cannibal Islands.” In addition, as early as June 6, 1830, a new song, “Chinaman’s

Boat,” in new play, was said to be sung to the tune of “Hokee Pokee” (presumably “The King of the Cannibal Islands”).xxiii

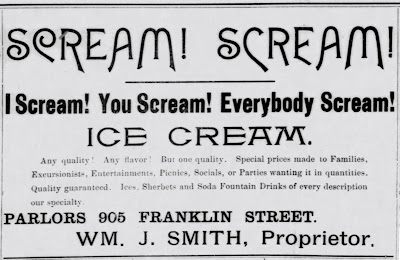

The Drink

In November of 1831, a “beer-shop” opened in the London borough of Hackney, named “Hokee Pokee” and serving drinks called “Hokey Pokey.”

March of Intellect. A beer-shop has recently been opened in Wells-street, Hackney, called “The Hokee Pokee and a Pot of Mild;” where ales are sold, bearing the following quaint

names, at per pot, viz.: “Hokee Pokee, sixpence; Ram Jam, fivepence; Tom and Jerry, fourpence; and Tiddley-wink, three-pence; drawn mild in your own pots.”

Jackson’s Oxford Journal (Oxford, England), November 26, 1831, page 1.

Something called “Hoky Poky” was apparently served at Queen Victoria’s wedding reception.

. . .

Her majesty led the way, sir, to cocoa and bohay, sir,

Tay-tay and coffee-tay, sir - the prince he was our host;

Of eggs there was no stricture, the beef it was no fixture,

And the hoky-poky mixture diluted well the toast.

. . .

“A Full, True, and Particular Account of Her Majesty’s Marriage with his Royal Highness Prince Albert,” Patricius Terentius Thadaeus O’Toole, Fraser’s Magazine

for Town and Country, Volume 21, Number 125, May, 1840, page 589.

The Races

A horserace called the “Hokee Pokee Stakes” was run every year from 1831 through at least 1845, and numerous horses were named “Hokey Pokey” (or variant spellings)

for many decades.

Hokey Pokey Rulers

Although “Hokey Pokey” in the original song appears to have been meaningless gibberish, intended to represent the sound of an unfamiliar island language, it soon came to be widely

used as he name of the king in the song, or as a placeholder name of any ruler of any remote South Seas or Pacific island. “Hokey Pokey” or the “King of the Cannibal Islands” would also be used more

generally, as a point of comparison for the legitimacy or sophistication of any ruler, politician or leader.

In 1831, for example, Robert Taylor, who was twice convicted of blasphemy, delivered a sermon in which he discussed the difficulty of missionary work in the region, due to the difficulty in

translating and explaining figurative language in religious works.

“We stick to the Cross, we suck the blood, and we loll our tongues in the very wounds of our Redeemer.”

There can be no doubt at all, that this is figurative language. Only one cannot help sympathising with the liability of its being misunderstood, when preached by our missionaries to convert

the blubber-lipt and copper-coloured souls of our brothers and sisters in the pacific Ocean, - such as “Hokey, Pokey, Wankee, Fum, And the King of the Cannibal Islands.”

Especially when ‘til taken into the account, that the missionaries themselves could no more explain the meaning of those figures of speech to the cannibals, than the cannibals could

to them.

“A Sermon, Preached by His Highness’s Chaplain, The Rev. Robert Taylor, B. A., at the Rotunda, Blackfriars-Road, April 3, 1831,” The Comet, Volume 1, Number 16, November 18, 1832, page 245.

When the Reform Act of 1832xxiv went into effect in Great Britain, a political song celebrated King William IV’s approval

of the new law - to the tune of “The King of the Cannibal Islands.”

The Glorious Bill of Reform.

Tune - “Hokee Pokee,” or “The King of the Cannibal Islands.”

Oh! have you heard the great event,

About the King in Parliament,

Giving, at last, his royal assent

To the glorious Bill of reform, Sirs? . . . .

The Examiner (London), June 10, 1832, page 11.

In 1833, in an article critical of oppressive slave laws in southern states of the United States, the author compared the legitimacy of any government that would permit such travesties to

that of the “King of the Cannibal Islands.”

One question to Europe, or such parts of it as this may ever reach. Is it creditable that a resident from such a country as this, should be received by any government, except on the same

kind of terms as a messenger from the King of the Cannibal Islands?

Review of James Stuart’s, “Three Years in North America,” The Westminster Review, Number 36, April 1833, page 351.

In 1833, an article critical of the English public’s eagerness to lend public assistance in the event of tragedies reported in exotic, far-flung places, and relative lack of empathy

with domestic problems.

Our philanthropy is equally remarkable. The more distant from us is the object of our solicitude, the greater is the interest we feel. Our operatives may starve at home, children may be

sold as slaves to the cotton spinners of Lancashire - sailors may be dragged as slaves to fight for their country, and be hanged as felons if they re-assume their birthrights, which they have defended with their blood - we

heed not all this; but if a South Whaler was to bring home authentic intelligence of a disastrous hurricane, with applications for relief from the dominions of “Hoky Poky, the King of the Cannibal Islands,” we should prick up our ears, call a general meeting, and raise a munificent subscription.

“Chit Chat,” Metropolitan Magazine, January 1833, page 28.

That same year in the same magazine, an article critical of England’s failure fully capitalize on its nominal possession of Hawaii was equally critical of England’s aristocracy

for having given the full royal treatment to the supposedly undeserving King Kamehameha II and his entourage a decade earlier.

It may be recollected that some years back, we had a certain set of savages brought over here, who were introduced as kings and queens of the Sandwich Islands. hey were feted, attended upon

by noblemen, and, in short, it was as splendid an instance of gullibility and tom-foolery as ever was witnessed in the most credulous of all the islands in the known world. Hoky Poky, the king of the Cannibal Islands, would receive an equally kind reception if he really were an existent being, and would condescend to make an appearance.

These black comets, however, took their departure, and of the whole of them one only is left,xxv

(Mrs. Boki,) who may be seen in a state of nudity and dead drunk upon the beach of Woahoo [(Oahu)], every day of her waning existence.xxvi

“The South Seas,” Metropolitan Magazine, April 1833, page 131.

Later that same year, a review of a play attended by a famous sea captain and some Lords of the Admiralty referred to the King and Queen of Tahiti (Otaheite) as “Hokee Pokee and his

wife (or whatever was the name)”.xxvii

The expression and dismissive tone might also applied to Westerners. It was played by a band hired to play on election day, in a manner the reporter found to be derisive.

The band employed by the two worthy Baronets amused themselves throughout the day (we suppose in derision of the absurd attempt of their employers to oppose Lord Eliot’s return) by

playing - “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” with its “Hokey Poky” chorus . . . .

The Royal Cornwall Gazette, Falmouth Packet, and General Advertiser (Truro, England), August 11, 1837, page 2.

In 1849, the expression was applied to George Byng, 7th Viscount Torrington, who was criticized for the cruel exercise of authority as Governor of the island nation of Ceylon.

King Torrington of the Cannibal Islands.

His lordship was originally a lord of the bedchamber (a kind of old-fashioned utensil not very distinguished), and subsequently a director of a railroad, in which last capacity, we presume,

he acquired that taste for collisions which has marked his administration. Of his recent cruelties it would be idle to complain seriously, since the Whigs seem rather to consider them honourable than otherwise; but as he

has more resembled the celebrated King of the Cannibal Islands than any other governor that has come under our notice, we think his career ought to be done justice to, in such a song as that which preserves to posterity the

character of this great prototype: -

Air, - “The King of the Cannibal Islands.”

Oh! have you heard the news of late,

About a great Whig potentate,

Sent out to rule a foreign state,

As king of the Cannibal Islands?

. . .

“Enough,” they say’s “as good as a feast,”

But what is enough of blood for a beast?

To a murdered mob he must add a priest,

This king of the Cannibal Islands.

. . .

Hokey, pokey, winkey fum,

to what strange plights must a country come,

That leaves a colony under the thumb

Of this king of the Cannibal Islands.

The Puppet Show, Volume 3, Number 52, March 3, 1849, page 84.

In preparation for the London Exhibition of 1851 (considered by some as the “first real World’s Fair”xxviii),

one wit imagined appropriate places for certain dignitaries to arrange lodging. The King of Denmark might stay at the “Copenhagen House,” the Emperor of China at “the old site of the ‘Chinese Collection,’”

the King of Holland would stay at the “Princes of Orange” and other small kings at the “Crown and Sceptres,” and the American president “will be at (or in) the ‘Shades,’ in Oxford-street.”

But, he imagined, it would not be easy to find a place willing to house cannibals; and they might also need to take precautions to prevent local chimney sweeps from being mistaken for members of dark-skinned delegations to

the Exhibition.

The great difficulty seems to be, at present, to obtain quarters for Hokey-pokey-twankay-fum, the King of the Cannibal Islands. His carnivorous propensities are too well known to make waiters and chambermaids feel that they will be quite safe from his ravenous maw. . . .

With a degree of consideration that cannot be sufficiently admired, the chef de police, Mr. Mayne, has given orders that none of the sweeps in their glittering attire shall be seen out on

the day, lest they should be confounded with some of the gentlemen of the suite of Hokey Pokey, the Newab of Gudderampore, and the Rajah of Paugalabad. - United Service Gazette.

Manchester Examiner and Times, December 7, 1850, page 10.

Alternate versions of the same joke appeared in condensed versions in other papers.

Great Meeting of Sovereigns. - It is said that the Emperors of Austria and Russia, the King of Prussia, and other European monarchs, have engaged lodgings in London to attend the World’s

Fair. It is still doubted whether his ungracious Majesty, Hokey Pokey, &c., King of the Cannibal Islands, can be accommodated, on account of his loving his neighbors well enough to eat them. “Old King Kole” will be thar. The King of the Sandwich Islands will not.

Wilmington Journal (Wilmington, North Carolina), January 10, 1851, page 6.

When Queen Emma Kaleleonalani, the wife of King Kamehameha IV, visited Britain in 1867, a widely reprinted item claimed (perhaps tongue in cheek) that a band played “King of the Cannibal

Islands” as the Hawaiian national anthem.

It is related that when Emma, Queen of the Sandwich Islands, visited Dublin Castle, during her recent tour in Great Britain, the Lord Lieutenant ordered the leader of the regimental band

to play the Hawaiian national air, when he at once struck up with the soul stirring strains of, “Hokey-pokey Winky-wang, King of the Cannibal Islands.”

Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee), April 27, 1867, page 2.

When the Fiji islands were ceded to Great Britain in 1874, several newspapers referred to the deposed King of Fiji as “Hokey Pokey” or “the King of the Cannibal Islands.”xxix

Now that Her Majesty Queen Victoria has taken the place of the latest successor “Hokey-poky-winky-wang, the King of the Cannibal Islands,” who has acquired much celebrity in song and story, it is quite probable that it will have a beneficial effect upon

the future of his carnivorous majesty’s realm.

Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee), November 9, 1874, page 1.

The joke reared its head again when the Chief of Police of Fiji visited Philadelphia two decades later.

|

“Chief of Police from the Land of Hokey-Pokey-Winky-Wum,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 11, 1896, page 3. |

Hokey Pokey Characters

“Hokey Pokey” and “The Progress of a Lawsuit” were not the first stage productions to be staged in England featuring cannibal characters. Daniel Defoe’s adventure

tale, Robinson Crusoe, inspired a long line of stage productions, particularly popular (but not exclusively) as Boxing Night or Christmas-time pantomimes. Robinson

Crusoe pantomimes were staged regularly beginning as early as 1781.

From 1781 through about 1816, the Robinson Crusoe pantomimes were typically performed under the title, “Robinson Crusoe, or Harlequin Friday.” Beginning in 1817, they were frequently entitled, “Robinson Crusoe, or the Bold Buccaneers.”

The plays typically included a number of “savages,” sometimes referred to as cannibals, and most performances apparently ended with a popular “savage dance.”

After 1830, pantomimes with the “King of the Cannibal Islands” in the title were occasionally performed.

“The King of the Cannibal Islands.”

The pantomime, which was produced on Boxing Night (December 26 [1837]), was named the “King of the Cannibal Islands; or, Harlequin and the Fairy’s Cave.” It ran for ten

or twelve nights, and seems to have been very successful for the time.

The Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, February 16, 1889, page 9.

In the Christmas Harliquinade at Edinburgh, Scotland in 1840, “Hokey Pokey” was the name of the King of the Cannibal Islands, although the plot and song were revised from earlier

versions. The lyrics portray the king’s ruthless means of dealing with his “refractory Cabinet Ministers, viz, by swallowing them wholesale.”

The Premier goes first with a fine ragout;

The Chancellor next, and his woolsack too -

While the Lord Lieutenant makes Irish stew

for the King of the Cannibal Islands.

The Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland), December 31, 1840, page 3.

The King was also not above eating his own son, Prince Fuzzi Muzzi, at least not when he is very hungry. But luckily, “the royal offspring is saved by the joyful news, that ‘two

tender whites are on the island.” The timely appearance of the Fairy Marena saves the day, frees the prisoners and deposes the King and Queen, with a promise to restore them when or if they “overcome their Anthropophagistic

propensities.”xxx

Other pantomimes featured characters with names based on the lyrics of the song.

Theatre Royal, Adelphi. - Great Attraction. - The best Pantomime. . . . the new Pantomime of Harlequin and Poonoowingkeewangflibbeedeeflobeedeebuskeebang; or, The King of the Cannibal Islands, with splendid Scenery and Transformations.

The Morning Post (London), December 30, 1845, page 4.

The author of the pantomime this season is Mr. William Travers, and the title - familiar to the ears of every little boy in the kingdom - is as follows: - Okee Pokee Wonkee Fum. How do you Like your Taters Done? or, Harlequin and the Gorilla King of the Cannibal Islands.

The Morning Chronicle (London), December 26, 1861, page 3.

In the play, “L’Africaine; or, Queen of the Cannibal Islands” (F. C. Burnand, 1865), “Hokey Pokey Winky Wang” was the title conferred on the character, Vasco

di Gamma, when he married Selika, the Queen of the Cannibal Islands.

As early as 1860, the name name “Hokey Pokey” was frequently used as the name of a stock character in generations of Robinson Crusoe plays. Henry Byron wrote at least two separate Robinson Crusoe plays, “Robinson Crusoe, or Harlequin Friday, and the King of the Caribee Islands” (1860)

and “Robinson Crusoe; or, Friday and the Fairies” (1868). In the former, a character named “Hoop-de-dooden-doo” was the “King of the Caribee Islands,” and “Hokee Pokee” and

“Wanky Fum” were “Vagabond Indians, all rags and tattoos.” In the latter, “Hokypokywankyfum” was the “King of the Cannibal Islands.” In 1883, the senior class of Harvard University

staged a production of Robinson Crusoe, which (judging by the names of the characters) appears to have been based on Byron’s 1860 script.

James Burnley wrote a version of Robinson Crusoe in 1877, in which scene seven took place in the “Royal Wigwam of King Hokey Pokey.” A man named Charles Millward wrote another version for the same theater in 1878, with a “King Hokey Pokey”

and his wife, “Queen Winkey-Wang.” J. J. Blood wrote a Crusoe pantomime in 1888, with a character called “King Hokey-Pokey . . . who rules a tribe of very amusing blacks.”

Roger Wheeler wrote a version entitled, “Robinson Crusoe, a Musical Extravaganza in Verse in Four Acts,” in 1925, which was first performed in Boston. His version include two

cannibal characters, “Hokey Pokey” and “Flubdub,” who kidnap Friday for dinner, who is rescued in the nick of time by Robinson Crusoe. That play’s make-up and costuming instructions describe

“Hokey Pokey’s” appearance.

Hokey Pokey. Black sleeve. Tight shirt and tights. Short trunks over which is worn a straw skirt, vari-colored neckpiece. Skin cloak draped over back. Large feet. Make-up black with fright

wig and earrings.

Roger Wheeler, Robinson Crusoe, a Musical Extravaganza in Verse in Four Acts, Boston, Walter H. Baker Company, 1926, page 8.

In traditional English pantomimes, the “principal boy” was generally played by a woman, as was the case in most productions of “Robinson Crusoe.”

Women were strictly forbidden from ditching their long skirts, even on the stage, unless they were playing a male role. So, the short skirts and knee-high boots of the principal boy offered

Victorian gents the chance to catch a rare glimpse of a female leg.

“A Brief Introduction to British Pantomime,” Emily McLean, The Historic England Blog.xxxi

The women playing Robinson Crusoe did not necessarily attempt to portray themselves as realistic men. I have not found any images of “Hokey Pokey” or “Wanky Fum,”

but an image of Charles Lauri as “Man Friday” may give a sense of how ridiculous their make-up and costumes may have been.

|

“Miss Vesta Tilley, as

Robinson Crusoe,” “Miss Ada Blanche, as Robinson Crusoe,” and “Mr.

Charles Lauri, as Man Friday, in ‘Robinson Crusoe.’” |

How do you like your ‘taters done?

King Kalakaua of Hawaii, who reigned from 1874 to 1891, is reported to have played the song ukulele on at least one occasion, substituting the “Sandwich Islands” for “Cannibal

Islands.” In her memoir, Isobel Field (a step-daughter of Robert Louis Stevenson)xxxii recounted the entertainments at King Kalakaua’s supper

parties.

In a small place like Honolulu, teeming with gossip, the King’s late supper parties were whispered about as orgies, not only by the Missionaries, but among a number of those who were

much offended at not being invited to join them.

Though we were served sandwiches and champagne frappe, these were not drinking parties but a gathering of congenial spirits, chosen by the King, I realize now, for our ability to entertain

him. . . .

Kalakaua, sitting in a big red velvet chair, laughed heartily applauding our efforts. He would occasionally pick up a ukulele or a guitar and sing his favorite hawaiian song, Sweet Lei-lei-hua,

and once he electrified us by bursting into

Hoky poky winky wum

How do you like your taters done?

Boiled or with their jackets on?

Sang the King of the Sandwich Islands.

Isobel Field, This Life I’ve Loved, New York, Longman’s, Green and Co., 1938, page 175.

The King’s version of the song, with the line about how one likes their “taters done,” reflects an alternate set of lyrics that had been known since at least 1833. It is

unclear where, when or in what context it originated, but it was in circulation in Australia as early as 1833, and appears in print in both England and the United States decades later.

Ann Roberts, a dab [(skilled persons)xxxiii] at culinary preparation, was charged by her master with continually annoying

him, and quoting extracts from the times of Heliogabulus down to the King of the Cannibal Islands; in proof of her depth of research, one of her quotations of a particularly queer nature was the following: -

“Hokey, Pokey, Wankey fum,

How do you like your ‘tatoes done?

Give to me a mealy one,

Says the King of the Cannibal Islands;”

and no persuasion, no rhetoric could erase it from the tablet of her memory, in consequence she was brought before their Worships, who sent her to study at Gordon’s laboratory for two

months.

The Sydney Morning Herald, June 10, 1833, page 6.

The comic notion of listing several means by which a cannibal might prepare a meal was not new. In 1831, for example, a humorous bit about poetry of the “Jokey Pokey people”

from “Jokey Pokey Land” imagined cannibals discussing several ways to prepare human flesh, as opposed to potatoes.

Specimen the third: A song of triumph.

The foe-man he is dead! . . . Let’s chop off his head And eat him!

How shall we cook him? Spitchcock or toast him? Boil or roast him? Or stew him in cocoa-nut jam? Take him and hook him to yonder pole; We’ll have him hot And eat the whole: If we can

not - He’ll be nice to-morrow with salad of yam.

“No Article This Month,” The New Monthly Magazine, Volume 32, Number 127, July 1, 1831, page 84.

Perhaps the “potato” version of the song used potato as a proxy for people in a comic song about cannibals, similar to the 1840 Christmas Harliquinade in Edinburgh, in which the

revised lyrics suggest the Premier would make a “fine ragout” and the Lord Lieutenant an “Irish Stew.” But regardless of origin or meaning, the potato version remained familiar for decades.

The author of the pantomime this season [at the Pavilion] is Mr. William Travers, and the title - familiar to the ears of every little boy in the kingdom - is as follows: - Okee Pokee Wonkee Fum, How do you Like your Taters Done? or, Harlequin and the Gorilla King of the Cannibal Islands.

The Morning Chronicle (London), December 26, 1861, page 3.

In 1868, a song billed as, “Plantation Medley” included snippets of then familiar songs, each one blending into the next. The long forgotten “Hokey Pokey” and “how

do you like your taters done” appear alongside still familiar songs like “Camptown Races” and “Oh, Susannah.”

Plantation Medley

As sung by Ben Wheeler and Byron Christy.

. . .

De Camptown racetrack ten miles round, Du dah, du dah;

De Camptown ladies sing dis song, Du dah, du dah day.

I’se gwine to run all night, I’se gwine to run all day.

I’ll bet my money on de bob tailed. -

Boys of Kilkenny, they’re fine rovin’ blades . . .

. . .

- Oh Susannah, don’t you cry for me, I’m goin’ to Alabama wid my -

- Hokey, pokey, wanky, wum, How do you like your taters done?

Mealy ones or flowr’y one for -

- Ole King Crow, he’s de biggist tief I know,

He neber says nofin’, but - cah! cah! cah!

Christy’s New Songster and Black Joker, as sung and delivered by the World-Renowned Christy’s Minstrels, New York, Dick & Fitzgerald, 1868, pages 39-41.

Similar alternate lyrics appear in the sheet music for a song called, “Hokey Pokey,” sung in a stage play entitled, “Ernani.” This version suggests several preparations

for the “taters,” reminiscent of Bubba’s ode to shrimp in Forrest Gump.

O hokey pokey winky wum, how do ye like your taters done? I’m putting of them on to bile [(boil)], with cod liver ile [(oil)], I like em fried, I like em biled [(boiled)], I like em

mashed in cod liver ile [(oil)], O hokey pokey winky wum, How do ye like em done?

Hokey-Pokey, The Celebrated Trio Sung in “Ernani,” by Miss Lydia Thompson, Mr. Harry Beckett, and Mr. Hill, New York,

Wm. A. Pond & Co., 1869.

The potato line survived in pop-culture as part of a counting-out rhyme. Counting-out rhymes are chants used to determine participation in children’s games, like “Eeny, meany,

miney, moe.”

Hoky poky, winky wum,

How do you like your ‘taters done?

Snip, snap, snorum,

High popolorum, Kate go scratch it,

You are out!

Henry Carrington Bolton, The Counting-Out Rhymes of Children, New York, D. Appleton & Co., 1888, page 110.

Commentary accompanying the rhyme suggests the “first line is derived from a College song: “King of the Cannibal Islands,” and wonders whether “hoky poky signif[ies]

hocus pocus (=hoc est corpus)?”

Further illustrating how deeply the two, original “Hokey Pokey” songs had penetrated and persisted in the pop-culture, two other counting-out rhymes on the same page include other

lyrical elements borrowed, ultimately, from “The King of the Cannibal Islands” or “All in the Tonga Islands.”

Inky pinky, forie fum,

Cudjybo-peep, illury cum,

Ongry fongry, forie fy,

King of the Tonga Islands.

Kentucky

Hokey, pokey, hanky, panky,

I’m the Queen of Swinkey Swankey;

And I’m pretty well, I thanky.

Michigan.

The Counting-Out Rhymes of Children, page 110.

The alternate lyrics appear in a novel, entitled, Captured by Cannibals, published in 1889.

’Okey pokey winkey fum,

How d’ye like your praties done?

Saoked in vinegar, boiled in rum?

The King of the Cannibal Islands!’

Joseph Hatton, Captured by Cannibals, New York, James Pott and Co., page 133.

An alternate version of the song was published 1860, in a collection of songs sung at Amherst College. This version describes several ways in which human meat might be prepared for the King

of the Cannibal Islands - “Woman pudding and baby sauce, Little boy pie for a second course,” and describes the one meal that did him in - “He died of eating his Clergymen cold.”

The last words of the Monarch bold,

Were not bequeathing his lands or gold,

but warning all against Clergymen cold,

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

Chorus. - Hokee pokee, &c.

Songs of Amherst (published by the Class of ’62), Northampton, Metcalf & Co., 1860, page 48.

“Hokey”?

This may be a stretch, but the origin of “Hokey Pokey” as a cheap imitation of a king, and its later use as the name of a cheap imitation of ice cream, suggested to me that there

may be a connection between the word, “hokey,” standing alone, in the sense of “obviously contrived, phony”xxxiv or “obviously

fake, phony.”xxxv Some sources connect “hokey” to the stage-slang word, “hokum,” which in turn is believed related to “hocus

pocus” and influenced by “bunkum.”

As early as 1917, “hokum” was defined as theatrical slang for “’sure fire stuff,’ or dramatic material that, because it has always been tried with success, can

be fallen back on in a crisis by the performer.”xxxvi But as early as 1921, it could also mean the same as “bunk,”xxxvii

the short form of “bunkum,” which means “insincere or foolish talk,” derived from Senate debates in the early 1800s, by a Senator from Buncombe County, North Carolina.xxxviii

I have not found the smoking gun proving the connection, but there is a long history of using “hokey pokey” in a similar sense and similar contexts, meaning fake, contrived, or

phony.

In 1838, for example, the expression “hokey pokey” was used to describe a demonstration of a phony phenomenon called “animal magnetism,” in which the application of

magnetized nickel supposedly causes a “patient” to become “violently flushed” and their eyes to convulse “into a startling squint.” To test the supposed reaction, they replaced the piece

of nickel with a piece of lead.

Accordingly, the lead was used as unsparingly as it is in shallow water on board a ship, but with no effect, until one of the bystanders said, with much sincerity of feeling, “Do not apply the nickel too strongly,” when, wonderful to relate, all the previous symptoms returned with added force.

Mr. Wakley now thought that the farce had gone on long enough, and getting rid of Miss O’Key, politely informed Dr. Eliotson of the facts of the case, thereby insinuating that the whole affair was a species of “hokey pokey,” only fit for the court of the King of the Cannibal Islands.”

The Torch, September 8, 1838, page 301.

In a widely reprinted Christmas story, first published in the Chicago Times-Herald in 1895, the protagonist, Zeph, referred to the “spirit of Christmas” as “all hoky poky,”xxxix much as Scrooge would

have referred to it as “humbug.”

“My Mom nearly lost seven’y-one pounds in two secon’s last summer!

That’s a lotta Hokey Pokey!

Kansas City Times, June 15, 1928, page 24.

In response to a letter-to-the-editor critical of women drivers, an angry reader called his argument “Hokey Pokey.”

Sir - In reading over the mail bag, I read a letter signed Hokey Pokey. That is what it is, just hokey pokey or drivel.

Courier-Post (Camden, New Jersey), July 16, 1932, page 8.

Lester Berrey and Melvin Van den Bark’s American Slang Dictionary (2d Edition, 1952) lists “hokey-pokey” and “hokum” next to one another under the headings “Nonsense” and “Deception,” so the meanings are close enough to consider

a connection. I offer it here as a plausible origin. You be the judge.

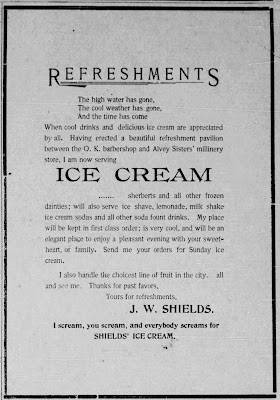

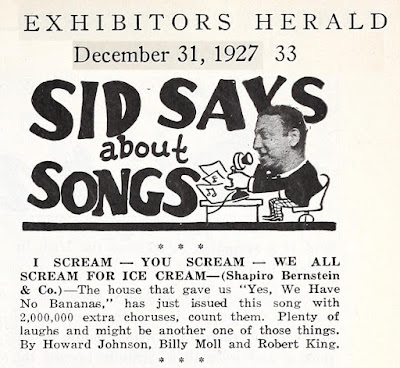

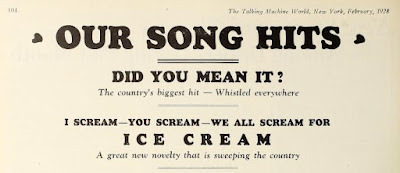

“Hokey Pokey” Frozen Treat

“Hokey Pokey” was at one time the name of a frozen dessert product sold by street vendors. Hokey Pokey was generally sold in rectangular slaps and wrapped in, or served on, paper;

the precursor to the now-familiar paper-wrapped ice cream squares, frequently Neapolitan. The description of what constitutes “Hokey Pokey” varies by time and place, but it was generally said to be an inferior

product to actual ice cream.

References to Hokey Pokey frozen treats first appear in print in London in 1878, where it was introduced by Italian street vendors.

A cheap imitation of the Neapolitan ice is known in the rough quarters, where it finds favour by the homely title of hokey-pokey. This consists of very bad cream and watery lemon ice cut

into square tablets, folded in white paper, and sold at the rate of two a penny.

Leeds Mercury, August 24, 1878, page 11 (and many other newspapers on the same date).

An American visiting London at about the same time noted the sale of “Hokey, pokey” ice cream, but also reported that the expression was used to sell “almost every thing.”

“Hokey, pokey, hokey pokey! Come and try my hokey pokey, shouts a frenzied man in yellow trousers and broad brimmed hat, “only a ha’ penny a cup!” I see that hokey

pokey in this instance is cream. The term is applied to almost every thing by London peddlers. “Hokey pokey,” bawls a little, dark faced man, with a bundle of hats in his arms: “a hat with a box for four

pence! Four pence for a hat!

Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), October 29, 1878, page 1.

If true, the general use of “hokey pokey” to sell anything may support the suggestion that “hokey pokey,” as used by street vendors, was derived from the Italian for

“Oh! how little it costs!.”

“Hokey Pokey.” - In Old London Street Cries and the Cries of To-day Mr. Andrew Tuer says that no explanation has hitherto been forthcoming of the ice vendor’s cry, “Okey pokey.” I take it that when the street trade in ices came in the Italian was first in

the field, and it is probable that he tried to attract attention to the comparative cheapness of his delicacies by the cry of “Oh! che poco costa!” (“Oh! how little it costs!”). He would want a cry,

and, knowing little English, might presumably employ one in his native tongue, which was perhaps caught up and shortened by his English rival into its present form.

Notes and Queries (London), 6th S. XII, November 7, 1885, page 366.

Whether applied generally at the time or not, the name would soon come to be applied exclusively to frozen treats.

Frozen Hokey-Pokey was introduced in New York City by 1880, also introduced by Italians.

Every day during the hot weather from fifty to 100 hokey-pokey ice cream carts can be seen in park row, says the New York Sun. The dealers are Italians. The hokey-pokey is made largely

of corn starch and milk. The principal manufactories are located in Goerk street. On hot days many of these itinerant venders retail twenty-five quarts of hokey-pokey at 1 cent a plate. The plates are made of brown paper.

Hamlin News Gleaner (Hamlin, Kansas), August 17, 1880, page 2.

And had penetrated the interior by 1885, when it was on sale in both St. Louis and Cincinnati.

Hokey-Pokey is being introduced in St. Louis.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 10, 1885, page 18.

Business Chances

The receipt with full directions and privilege of manufacturing and selling Hokey Pokey or Solidified Ice Cream; a handsome salary to any one entering the business even in a small way; cleared

in Philadelphia last summer over $17,000; parties running St. Louis are not clearing less than $100 per day. For terms and circular ad. Marshall Jones & co., 112 N. 3d st., St. Louis, Mo.

St. Louis Post Dispatch, May 16, 1885, page 7.

In Cincinnati, an early article about Hokey-Pokey frozen treats in the city invoked the lyrics of the “King of the Cannibal Islands” in introducing the new product to its readers.

Even if the word did not come from the old song, in the first instance, perhaps it caught on as the name of the inferior frozen product because of the sense of “Hokey Pokey” as an inferior king.

Hokey-pokey, winkey wung;

Polly-me-kue, come homily, cum;

Hangery, wangery, chingery, chang,

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

“Hokey-pokey! What the devil is hokey-pokey?” asked the Enquirer man.

Nobody knew.

An Irishman said it was Italian for ice-cream.

Somebody else said it was a sort of candy.

“Let’s try it?” and the Hokey-Pokey man was hailed.

“Give us some hokey-pokey,” and the descendant of the Caesars opened the ten-gallon ice-cream freezer that was fastened on a wheelbarrow, to which two extra wheels had been added,

making an original combination of cart and wheelbarrow. He drew fort he condiment, neatly wrapped, and received the essential coin in return.

It tasted rich and good, and spoons and saucers were not needed to consume it. It is solidified ice-cream, and you can eat a cake as you would a banana or pineapple, holding it in the paper

and throwing this away when consumed.

The Cincinnati Enquirer, July 13, 1885, page 8.

Hokey-Pokey! hokey-pokey!

Here’s the hokey-pokey man,

With his little cart and can,

Painted green and seeming neat

As the hokey-pokey’s sweet.

Where’s your money? Have you any?

You can purchase for a penny

Hokey-pokey, sweet and cold, -

For a penny, new or old. . . .

St. Nicholas, Volume 21, Number 8, June 1894, page 734.

In Boston, “hokey-pokey cart” became a euphemism for trash collectors’ push carts.

When the little push carts first appeared some sarcastic city father dubbed them “hokey-pokey” carts, on account of their close resemblance to the familiar ice-cream dispenser

which our Italian fellow-citizens wheel around in summer, and from which they retail rainbow-colored cakes of cream.

Boston Globe, May 4, 1891, page 8.

|

Boston Globe, May 4, 1891, page 8. |

|

Boston Globe, December 4, 1892, page 1. |

The Hokey-Pokey Man.

Written for the Evening Star.

Of all the horrid nuisances (deny it if you can),

The very horridest of all is the hokey-pokey man;

He rings his bell at morning, and he rings it in the night,

And when you say, “Please go away,” he rings and says, “All right.”

Oh, the hokey-pokey man!

He’s the terror of the mothers, he’s the children’s dear delight;

He rings his bell at morning, and he rings it in the night;

And when you say: “’Tis nasty stuff, not fit for boys to eat,”

He thrusts a package in your hand, and says: “Good! Very good, and sweet.”

Oh, the hokey-pokey man!

“Oh, can’t I mama? Please, five cents! Oh, mama, some I will!”

The children tease and threaten till they get their stomach’s fill;

And the vile old hokey-pokey man stands smiling in your face,

And says: “Yes, mum, ‘tis good for ‘em; I sells it every place.”

Oh, the hokey-pokey man!

And, though he sees the children a-squirm with stomach-ache,

He rings his hokey-pokey bell and cries: “Please, hokey-pokey take!”

And rings it in the morning, and rings it in the night,

Till life becomes a torment and one’s soul is filled with spite.

Oh, the hokey-pokey man!

. . .

I hope I’ll be forgiven, but I trust the day is near

When some one, just as crazed as I, will lay him on his bier.

I have a dangerous vision; maybe ‘tis a summer dream,

Wherein the horrid man is drowned in hokey-pokey cream.

Oh, the hokey-pokey man!

Washington, June 15, ’87. Marie Le Baron.

Evening Star (Washington DC), June 25, 1887, page 2.

Due to lack of oversight and lax or poor hygiene standards, much of what was written about “Hokey Pokey” over the years was about illness or death of its customers, and attempts

to ban its sale.

“Hokey Pokey” Kills Child.

Ice-cream sandwiches are held accountable for the death of Alma Gates, 13 years old, in Harlem today. The attending physician reported that there was evidence of ptomaine poisoning. The

parents of the girls said that Alma bought three “hokey-pokey” ice-cream sandwiches on Tuesday and ate them all herself.

The Baltimore Sun, April 15, 1904, page 10.

. . . The growth of the penny ice cream industry has caused the department to make a thorough crusade against the use of poisonous coloring and flavoring matters. Not only is the so-called “hokey pokey” said to be made of materials unfit for human consumption, but also much of the ice cream and soda that is peddled about the city.

The Standard Union (Brooklyn, New York), August 19, 1904, page 9.

Lynn, Aug 29 - Three cases of ptomaine poisoning, resulting from the eating of ice cream sold by hokey-pokey venders, have been reported to the board of health. The sufferers are all little children who purchased penny ice cream sandwiches on Monday.

Boston Globe, August 30, 1906, page 7.

To combat the problem, St. Louis established the office of “Hokey Pokey” inspector.

|

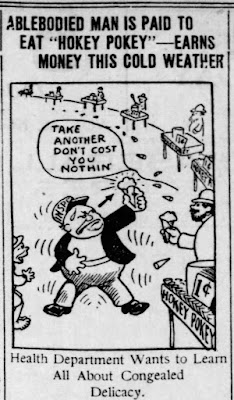

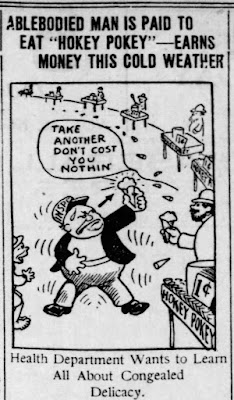

"Ablebodied Man is Paid to Eat 'Hokey Pokey' - Earns Money this Cold Weather." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 20, 1908, page 2. |

But under the heading of no good deed goes unpunished, when the “Hokey Pokey” inspector actually banned “Hokey Pokey” as dangerously unhealthy, some thought that perhaps

reform efforts had gone too far - depriving poor children one of the most beloved of the few diversions available to the “back street boy.”

Microbes in the “Hokey Pokey.”

In our steady progress toward the perfect uplift we have now reached the point where the offspring of poor but honest parents on the back streets may no longer be permitted to patronize the

“hokey pokey” cart, for State Factory Inspector Davies declares that the “hokey pokey” dispensed by the “hokey pokey” man, in quantities to suit the modest pocket allowances of the children

of the humbler class, is nothing less than “frapped microbes,” and is a menace to their health.

“Hokey pokey,” be it known, has all the appearance, flavor, and drawing quality of ice cream. Indeed, so far as the children who patronize the “hokey pokey” man are

concerned, they prefer it to any ice cream that ever was made. It comes in colors to rival the sunset, and is altogether fascinating, alluring, and seductive to the small boy and the little girl of the back streets. . . .

The Chicago Inter-Ocean, May 21, 1908, page 6.

The warnings and the ban, however, were not expected to change the behavior of the children, because “hungry childhood has scant reverence for the warnings of science when confronted

by something good to eat.”xl

“Hokey Pokey” Poker

Beginning in 1886, “Hokey Pokey” was a form of poker, first played in California. It’s not clear that all games that went by the name were the same game, as descriptions

vary. It was generally described as a variant of what they called “stud-horse poker,” but with more cards dealt up than in the original. It was invented to circumvent perceived loopholes in anti-gambling laws.

Efforts to evade prosecution were successful in places, and unsuccessful in others. Some jurisdictions revised the law to ban “Hokey Pokey,” by name.

The Hokey-Pokey Players.

[P]rior to the arrest of the defendants on the charge of conducting a game prohibited by law, they, the defendants, were apprised from an official source that they were about to be arrested,

and would be arrested at a certain hour named, and that some understanding or agreement was entered into between the defendants and some official, or officials, that this case should be a test case, and that by some understanding,

tacit or otherwise, the game being played at the time of the arrest was changed in some of its features so as to differ from the methods generally adopted in said game known as Hokey Pokey.

The Sacramento Bee, September 3, 1886, page 3.

Hokey Pokey is Different from Stud-Horse Poker, because in the latter game you conceal one of the five cards, and in hokey-pokey the first card is concealed and the others exhibited.

Sacramento Bee, September 4, 1886, page 5.

An article from San Francisco several months later, where multiple jury decisions established the legality of the game in that city, explain the game further.

“Hokey-Pokey.”

A Gambling Game that Has Spread Like Wildfire.

Dealers Who Have a “Sure Thing” on Players.

How such a peculiar name as “Hokey-Pokey” ever became saddled to the gambling craze of the hour is a veritable mystery, equaled only, perhaps, by Topsy’s idea of her origin.

. . .

I remember it started a few weeks after stud-horse poker was stopped by the police. Stud was a great game; played like hokey-pokey, only in the latter game four cards are dealt each of the

players instead of five. . . .

He reserved the right, however, and he made it his strong point that the game would charge for the cards used and the drinks consumed. To meet these expenses, a dealer was put into the game,

and each deal he was supposed to take out a small portion of the “pot” or wagers made by the players. This system, which is the real hokey-pokey of today, proved very successful for the house, met apparently for

a while with the consent of the authorities, and began to be played throughout the State. In the Western Hotel at Sacramento the next game was started, and that was its main introduction to the public.

. . . The lower courts decided that “Hokey-Pokey” was not against the laws.

The San Francisco Examiner, February 13, 1887, page 8.

Does “Hokey Pokey” refer to the game being a poor imitation of actual poker, or of stud-horse poker? Or does a comment in one witness’ testimony about the game suggest a

cooler origin. Is it “Hokey Pokey” because it’s similar to a game called “freeze-out” - like frozen “Hokey Pokey”?xli

On cross-examination the witness said that he regarded that the proprietor got a percentage, as he runs the bar. He admitted that he had seen persons playing “freeze-out” at other places receive checks for drinks, and thought the principle about the same.

Sacramento Bee, September 4, 1886, page 5.

It is possible that the name was applied to the card game because of some similarity, or that it alluded to it being an imitation of stud-horse poker, or both. It may also have been a completely

unrelated use of a funny name by whoever invented the game.

Do the “Hokey Pokey”

The “Hokey Pokey” dance craze first took root among soldiers in WWII. Jimmy Kennedy wrote a song called the “Cokey Cokey” in early 1942, which was soon referred to

as either the “Hokey Pokey” or “Hokey Cokey.” When introduced in the United States the following year, it was called the “Hokey Pokey,” and it retained that name as it spread across the

country in USO dances and shows. In Britain, the dance is still generally referred to as the “Hokey Cokey” (“Cokey,” by the way, was then slang for a cocaine addict, which may put the shaking and turning

in another light).

In 1949, an American named Larry LaPrise wrote a song he called the “Hokey Pokey,” which he performed along with his trio at ski resort in Sun Valley, Idaho. Many consider his

composition to the the familiar song we know today as the “Hokey Pokey” (or “Cokey”). He filed for copyright protection of his song in 1950 and earned many royalties over the years. He claimed to

have based the song on a French song he learned from his father.

Laprise’s claim to have written the song, however, is strained in light of the fact that an earlier recording of Kennedy’s song sounds suspiciously similar to his own song.

Compare, Lou Preager and His Orchestra’s 1945 recording of Kennedy’s, “The Cokey Cokey,” with the Sun Valley Trio’s 1950 recording of Laprise’s, “The Hokey Pokey.”

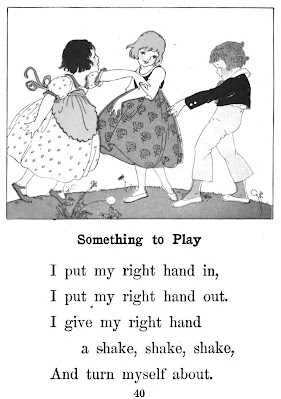

But although a song and dance, by that name and with the line about it being “what it’s all about, first appeared in 1942, the basic dance move instructions to put one’s

foot, etc., in and then out and to shake them about, date to at least the 1840s. The earliest known reference to them is in the book, Popular Rhymes of Scotland, 2d Edition (1842). The instructions for the movements were known in the United States during early 1900s, appearing in numerous music books and children’s

activity guides.

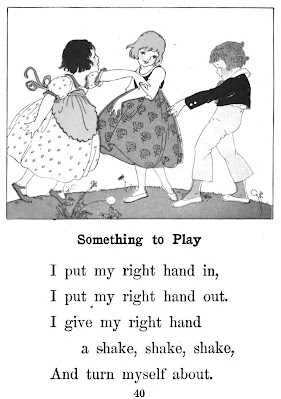

|

Fannie Wych Dunn, Everyday Classics, Primer-Eighth Reader, New York, Macmillan, 1917, page 41. |

For a more detailed and in-depth look at the history of the “Hokey Pokey” (or “Cokey”) dance craze, see my post: