|

Sep. Winner 1868.

|

In its simplest, most familiar form, the song, “Ten Little Indians,” appears to be an innocent children’s counting song.

One little, two little, three little Indians,

Four little, five little, six little Indians,

Seven little, eight little, nine little Indians,

Ten little Indian boys.

Ten little, nine little, eight little Indians,

Seven little, six little, five little Indians,

Four little, three little, two little Indians,

One little Indian boy.

HooplaKids YouTube; KidsCamp YouTube; Muffin Songs YouTube; LIV Kids YouTube.

Yet there are some who worry that the song was derived from earlier problematic versions of the song, in which ten little boys (Indians or N[-words]) disappear or die off, one at a time,

in ten ludicrous and macabre ways. But most people have the timeline confused. The familiar, simple, innocent version is not derived from the problematic versions - it’s the other way around. The simple version predates

the problematic versions by nearly two decades.

The Gibson family singers published the original sheet music in 1849, with lyrics and music nearly identical to the familiar children’s song as sung today.

One litle two little three little Ingins,

four little five little six little Injins,

seven little eight little nine little Ingins,

ten little Ingin boys.

Gibson Family (1849)

Septimus Winner wrote the original problematic version, with “Injun boys,” at a neighborhood children’s party in about 1864, and published sheet music for the song in the

first few months of 1868. Months later, an English songwriter named Frank Green adapted Winner’s melody to lyrics with “N[-word] boys.” That song was introduced on stage in 1868 at St. James Hall, London,

by George Washington “Pony” Moore of the Christy Minstrels.

Winner’s version differs in significant ways from the original. Whereas the Gibson family’s version is limited to simply counting up and then counting down, Winner’s version

has ten verses with the counting chorus between each verse. The chorus is similar to the original, but with only two counting segments (1-5 and 6-10), instead of the traditional four (1-3, 2-6, 7-9 and 10). And he changed

the melody.

One little, two little, three little, four little, five little “Injun” boys;

Six little, seven little, eight little, nine little, ten little “Injun” boys.

Mark Mason (one of Sep. Winner’s pseudonyms), Ten Little Injuns, Philadelphia, Sep. Winner & Co., 1868.i

Winner’s ten verses were a completely new addition to the song. The first nine verses describe the disappearance or death of one boy at a time, reducing the number to one. In the

tenth verse, the last boy gets married and raises ten more boys, bringing the number back up to ten.

The verses were new, but not without precedent. They appear to be based on a song about “Ten Little Blackbirds,” from a children’s book published in 1858. Winner’s

song borrowed the countdown disappearance format, and even borrowed several rhyming word-pairs exactly.

Nine little blackbirds sitting on a gate,

One flew away, and then there were eight.

Eight little blackbirds flying up to heaven,

One flew away, and then there were seven.

Children’s Holidays: A Story-Book for the Whole Year (1858).

Nine little Injuns swinging’ on a gate,

One tumbled off, and then there were eight.

Eight little Injuns never heard of heaven,

One kicked the bucket, and then there were seven.

Septimus Winner, Ten Little Injuns (1868).

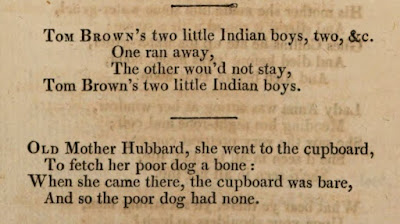

Like Winner’s version, the Gibson family’s version was also based on earlier material. It appears to be an elaboration on a traditional English nursery rhyme, “Tom Brown

had two little Indians,” which appeared in print as early as 1810. The two Indians in the nursery rhyme disappear, but not in cruel or unusual ways. They were portrayed as independent actors, leaving on their own accord

and in their own self interest.

Tom Brown’s two little Indian boys, two, &c.

One ran away,

The other wou’d not stay,

Tom Brown’s two little Indian boys.

So, if anything, the modern, children’s song is based on a more-or-less positive portrayal of two independent boys seeking their own freedom, and not on the later, problematic, racist

versions of the song.

A precursor to “Ten Little Blackbirds” also shares similarities with “Tom Brown’s Two Little Indian Boys” - there were two, and they each leave independently.

There was two birds sat on a stone;

One flew off, and then there was one;

The other flew after, and then there was none.

The Monthly Mirror (London), Volume 2, August 1796, page 250.

There is more to the story. There is some indication that there may have been more extensive counting versions before the Gibson family’s 1849 version. Their sheet music even says

that it was “arranged by,” not written, by them. And a few problematic versions appear as early as 1859, mostly in connection with criticism of the abolitionist, John Brown, apparently influenced by the similarity

of his name to “Tom Brown” of the traditional English nursery rhyme. Those versions, however, appear to be one-off, political commentary, without the ten disappearing verses, and likely unrelated to Septimus Winner’s

song of a decade later.

Most of the commentary about the origin of Ten Little Indians and Ten Little N[-words] reflects a lack of awareness of the traditional nursery rhyme, the original, Gibson family version of the song, and the song,

Ten Little Blackbirds. As such, they assume that the problematic versions came first, giving rise to discomfort singing an otherwise innocent version of the song

supposedly “based on” the racist song.

But if the original versions were more-or-less innocent, and the problematic versions merely later aberrations which have since been largely abandoned, perhaps a return to the original should

be welcomed not discouraged.

You be the judge.

Traditional English Nursery Rhyme

Tom Brown’s two little Indian boys, two, &c.

One ran away,

The other wou’d not stay,

Tom Brown’s two little Indian boys.

This rhyme appeared in a collection of traditional nursery rhymes as early as 1810, suggesting it may date to the 1700s, or earlier. Given England’s presence in India, the West Indies

and North America at the time, it is not clear to which ethnic group the “Indian boys” of the nursery rhyme belonged.

Grammer Gurton’s Garland: Or, the Nursery Parnassus, London, Harding and Wright, 1810, page 37.

The “two little Indian boys” of this rhyme appear to pre-figure “[X] little Indians” of the later songs, and the disappearance of the original “two little Indian

boys” may be inspiration for the successive disappearances in some of the later versions of the song. Although the “&c” (et cetera) in the first line suggests the possibility of additional, sequential verses with successive numbers of boys, all of the other early examples of the song I have seen are

limited to the one verse with two boys, without any additional verses or signals suggesting additional verses.

The verse appeared in print in the United States in 1833, in a collection of “Mother Goose Melodies,” and in 1842, in a collection of “Early English Poetry, Ballads, and

Popular Literature of the Middle Ages,” and a collection of “Nursery Rhymes of England.”

Mother Goose Melodies, 1833, page 51.

Nursery Rhymes of England, 1842, page 110.

This short, simple rhyme remained in print in various other collections of “Mother Goose” rhymes for more than a century. And although it appears to have been outpaced in popularity

by later, more extensive versions of counting songs, this version remained familiar to some. For example, in article about the Mono Indians along the San Joaquin river in California, the writer used it to illustrate the difficulty

of photographing children. He may, however, have conflated the nursery rhyme with later versions of the “Ten Little Indians” song, which were frequently characterized as “college songs,” not thought

of as nursery rhymes.

A little later I made an attempt to corral some of the boys and girls for a photograph, but when I placed some and went for others, I would return only to find that the first party had escaped.

Like Tom Brown’s two little Indian boys, celebrated in college song,

One ran away,

And the other wouldn’t stay.

“A Day with the Mono Indians,” W. B. Noble, D. D., Out West, Volume 20, Number 5, May 1904, page 413.

Extended Counting

Early references to “Tom Brown’s two little Indian boys” all start and stop with two. Apart from the cryptic “&c.” in one of those references, there is

no indication that the traditional nursery rhyme involved counting up or down beyond two. In the 1830s, however, at least two comments appeared in print suggesting that there may have been traditional versions involving counting

up or down beyond two.

In March of 1832, Lord Plunkett (William Plunkett, 1st Baron Plunkett), then the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, was embroiled in a controversy about nepotism, having (allegedly) improperly appointed a number of family members to offices drawing emoluments from the public

treasury. Numerous newspaper articles listed the family members, their appointments, and the amounts of money said to be involved. The London Evening Mail reportedly printed commentary about the affair, apparently based on “Tom Brown’s Two Little Indian Boys.” This is the earliest example I have seen

of any such song that goes up to the full number of ten.

Like as are the Whigs to magpies in chatter, they are far liker them in thieving. . . . And there is my countryman, Plunkett, with the whole tribe of his high-born family. . . . I was like

to die of laughing at a song about the one little Plunkett, two little Plunketts, and so on to the ten little Plunkett-boys, which I read in the Evening Mail, at the Athenaeum some days ago. Remmy is a droll hand at a bit of fun; but, on reflection to myself, I could not

help thinking all such things pleasant, but wrong. . . .

Dawson was very good; he made a capital speech, in which he proved that if Lord Plunkett was not Lord Bacon in point of talent, he had some points of resemblance to that great man.

“Epistles to the Literati, No. 111, Letter of William Holmes, Esq., M.P., to Archibald Jobbry, Esq., Ex-M.P.,” Fraser’s for Town and Country, Volume 5, Number 27, April 1832, page 376 (reprinted, The Examiner (London), April 8, 1832, page 11).

It is unclear whether the reference to a “song” about the “ten little Plunkett boys” refers to an article in the Evening Mail actually counted off Plunketts as in a song, perhaps written by someone called “Remmy,” or whether the writer (William Holmesii)

was merely suggesting that a list of Plunketts in Dawson’s speech reminded him of such a song.

The Evening Mail is available in an online British newspaper archive. I was unable (in a brief search) to locate the “song”

Holmes described having read. But the Evening Mail did report George Robert Dawson’siii speech

about Plunkett’s alleged misdeeds. Dawson listed no fewer than six Plunketts, two in-laws and another who supposedly benefited from Lord Plunkett’s suspect appointments.

The following was the account of the offices and emoluments enjoyed by this family: - Lord Plunkett, Chancellor, 8,000 l.; the Hon. P. Plunkett, Purse Bearer, 800 l. . .; the Hon. D. Plunkett, Prothonotary of the Common Pleas, 1,500 l. . . . the Hon. J. Plunkett, Assistant Barrister in the county of Meath, 700 l. . .; the Hon. and Rev. F. Plunkett, Dean of Down, 2,500 l.; the Hon. and Rev. Wm. Plunkett, Vicar of Bray (loud laughter), 800 l.; Mr. M’Causland, jun., 2,000 l.; Mr. Long, 500 l.; Mr. Wm. M’Causland, brother-in-law of Lord Plunkett, and father of the young

man, 1,500 l.; besides various other lucrative situations . . . .

Evening Mail (London), March 7, 1832, page 7.

In any case, the reference to a song about “one little . . . two little . . . ten little . . . boys” suggests the possible existence, at that time, of a traditional counting

song similar to the modern version of the song.

Also in 1832, the poet and novelist, Letitia Elizabeth Landon, made a comment apparently alluding the a “little Indians” counting song. In a letter to Thomas Crofton Croker

(published years later), she was apparently discussing drafts of works she was sharing with him for comments.

1832. Dear Mr. Croker, I sent ‘two little, three little Indian boys,’ for which I have been very industrious in picking out notes.

“Correspondence between Miss Landon and Thomas Crofton Croker,” edited by T. F. Dillon Croker, Sharpe’s London Magazine of Entertainment and Instruction for General Reading, Volume 20, New Series, 1862.

The published letter does not explain her remark, and a cursory search through both volumes of The Works of L. E. Landon (1841) reveals no obvious work that might correspond to her cryptic

reference. She may have been referring to her draft articles as the “little Indian boys” in question (two little, three little articles?). But her use of those words, and her choice to set them apart in quotes,

seem to reflect the potential existence then of something like the modern counting song, even before the Gibson family published their arrangement of the familiar words and melody in 1849.

Gibson Family - 1849

The Gibson Troupe of singers published the first known version of the now-familiar “Ten Little Indians” song in 1849. The song leads off with a line similar to the traditional

English nursery rhyme, but with the name changed to “John.” The melody and rhythm is nearly exactly the same as the one modern version, except that the melody goes up instead of down in the last line.

Interestingly, the title page information does not claim authorship of the song, but merely that it was “arranged by J. Gibson,” raising the question of whether this longer version,

in one form or another, may have been in existence prior to publication of their version. In any case, the lyrics and melody show that the basic version of the song most people in the United States still learn at a young

age dates to at least 1849, two decades before Septimus Winner’s problematic versions.

“Old John Brown,” Solo and Chorus, Arranged by J. Gibson.

Old John Brown had a little Ingin,

Old John Brown had a little Ingin,

Old John Brown had a little Ingin,

One little Ingin boy.

One little two little three little Ingins,

four little five little six little Ingins,

seven little eight little nine little Ingins,

ten little Ingin boys.

Ten little nine little eight little Ingins,

seven little six little five little Ingins,

four little three little two little Ingins,

One little Ingin boy.

Sheet music viewable at Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries.iv

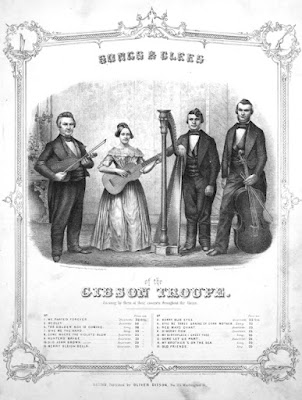

I could find very little information about the “Gibson Troupe” or Gibson family singers. In concert, they played the “violin, guitar, harp and the violincello,”

as pictured in the cover art for their sheet music.

“Mr. Gibson, senior” was said to be a “distinguished composer of music. Fall River Monitor (Massachusetts), April 14, 1849, page 2. Their performance in Greenfield, Massachusetts in November, 1849 was said to be “one of the

best that has ever been given in this place.” The Recorder (Greenfield, Massachusetts), November 26, 1849, page 2. And following a concert in Meadville, Pennsylvania, one listener was so enraptured by the sound of Sarah Gibson’s voice, that he composed a poem in honor of it. The

poem appeared next an advertisement for an upcoming concert in Pittsburgh.

IMPROMPTU

On hearing Sarah Gibson, of the “Gibson Family,” sing.

By G. V. Maxham.

Methinks I hear the sweet-voiced Robin singing,

As I have heard her sing before,

When from a distant, sunny shore

She came the pleasant May and blossoms bringing;

. . .

Begone, ye doubts within my brain upspringing,

I’m sure it is a blessed robin singing!

Meadville, Pa., Oct. 28th, 1850.

Pittsburgh Daily Post, March 4, 1851, page 2.

The critics were unanimous (at least those whose reviews their agent shared to promote upcoming performances).

The Gibson’s are Coming.

We have received a note from the Agent saying that the Gibson Family, “of the Old Bay State,” will give a Vocal Concert in this place int he course of a few days. We copy the

following from the many complimentary notices of these Vocalists by the press:

“The Gibsons are the best Quartette now singing.” - Boston Post.

“They are one of the best quartette companies now singing.” - Boston Atlas.

“The Gibsons are certainly a model quartette, and will undoubtedly improve the taste of quartette choirs who may hear them. Our choirs, especially in the country, are sadly deficient

in articulation, and the faculty of throwing the whole soul into the music they are performing, whether sacred or secular. As modes of articulation and expression we recommend all singers to hear the Gibsons.” - Philadelphia Ledger.

Portage Sentinel (Ravenna, Ohio), November 4, 1850, page 2.

References to the Gibson family disappear by the mid-1850s, but if they are the ones who helped popularize “Ten Little Indians,” their legacy still persists to this day. References

to their version appeared a few years after publication.

In 1853, for example, the mother in a children’s book sang an alternate version of the song to distract her daughter from her burned hand.

Susy Miller, she burnt her little finger,

Susy Miller, she burnt her little finger;

Susy Miller, she burnt her little finger.

One little finger burnt;

One little, two little, three little fingers,

Four little, five little, six little fingers;

Seven little, eight little, nine little fingers - Nine little fingers burnt!

Little Susy’s Six Birthdays, by her Aunt Susan, New York, Anson D. F. Randolph, 1853, page 108.

An 1859 review of a book by a man named John Brown described the song bearing his name (no relation). By way of explanation, “amphisbaenic” means “serpentlike,”

moving forwards then backward - there is no suggestion of the disappearances or deaths in later, problematic versions of the song.

We are all familiar with that John Brown whom the minstrel had immortalized as being the possessor of a diminutive youth of the aboriginal American race, who, in the course of the ditty, is

multiplied from “one little Injun” into “ten little Injuns,” and who, in succeeding stanza, by an ingenious amphisbaenic process, is again reduced to the singular number. As far aw we are aware, the

author of this “genuine autobiography” claims no relationship with the famous owner of tender redskins. The multiplicity of adventures of which he has been the hero demands for him, however, the same notice that

a multiplicity of “Injuns” has insured to his illustrious namesake.

The Atlantic, Volume 3, Number 20, June 1859, page 770 (review of, Sixty Years' Gleanings from Life's Harvest, a Genuine Biography. By John Brown, Proprietor of the University Billiard-Rooms, Cambridge, New York: Appleton & Company. 1859).

In 1859, a freshman at Yale used the song as a literary device to frame his essay on the history of North American Indians on the continent.

The Freshmen are being initiated into the “art of composition.” Having received, from the Professor of English literature, the following subject, to exercise their youthful minds,

viz: “The North American Indians; an account of the probably concatenation of fortuitous events that threw them, on the shores of this wide spreading continent, &c., &c.,” they evidently “laid themselves.”

One of their number introduced his composition by the following extract from the author of the “King of the Cannibal Islands,” or Shakspeare -

The Yale Literary Magazine, Volume 24, Number 8, July 1859, page 383.

And in 1867, one year before Septimus Winner’s more elaborate versions of the song appeared in print, the Gibson family’s version appeared in a Yale songbook.

Ferd Garretson, Carmina Yalensia, A Complete and Accurate Collection of Yale College Songs, New York, Taintor Bros., 1867.

John Brown - Abolitionist

In October 1859, the abolitionist John Brown led a raid on the United States’ arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. His plan was to arm, inspire and lead an insurrection and

rebellion against the institution of slavery. It failed. But his name was adapted in a satirical version of the old song, with N[-word] substituting as the unit of counting. The song was intended to illustrate how Southern

interests exaggerated the uprising for political purposes. It mirrored, for the most part, the Gibson family version, counting up to and down from ten, but with the “Democratic Press” claiming “ten thousand little n[-word] boys, all armed with pitchforks eighteen feet long and commanded by twenty thousand Abolitionists.”

It has served the purpose of one section of the moderate and southern party to exaggerate the late insurrection, with the view of bringing the abolitionists and the free-soilers into greater

odium, and so damage their chances at the state and presidential elections. A witty exposure of this system appears in the ‘New York Evening Post:’ -

The Monthly Christian Spectator, Volume 9, December 1859, page 767 (reprinted widely beginning as early as October 27, 1859, perhaps

originating with the New York Evening Post.).

The association of his name to the song was likely due to the similarity between his name and the name “Tom Brown” in the traditional nursery rhyme, or “John Brown,”

as the nursery rhyme had coincidentally been adapted by the Gibson family a decade earlier. Other mentions of John Brown illustrate a general awareness of the similarity of his name to the one in the old song or rhyme.

Boot-black No. 1 to Boot-black No. 2 - Oh, Davy! look er ‘ere! ‘Ere’s a picter of Old John Ossalwatamus Brown!

Boot-black No. 2 - What! Old Brown what had a little Injun?

No. 1 - No, zer blasted fool! Hits Old Kansas Brown What’s tried to run orf with all Gov. Wise’s Virginny n[-words],

and got cotched at it, and is going to be hung next week at 9 o’clock.

New York Tribune, November 11, 1859, page 7.

We notice that the Alton papers are in a squabble over a poem published in the columns of one of them, glorifying the valor, christianity and immortal martyrdom of John Brown. This is not

the Old John Brown that “had a little Injun,” nor any other Brown except “Old Ossawatamie,” of Harper’s Ferry notoriety, deceased.

Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis, Missouri), November 23, 1862, page 2.

John Brown was not the only person whose name was worked into a version of the song. Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant) was rumored to have fathered multiple children out of wedlock

with a Native-American woman, his name received similar treatment.

The Times-Democrat (Lima, Ohio), August 12, 1868, page 2.

Early Macabre Version

There was at least one John Brown verse or rhyme, in which counted boys disappear or die in gruesome ways, and published before Septimus Winner’s versions. In 1856, the following

rhyme made it into print. The number of children is three, not the traditional two and not the later ten. It is the only such reference I found.

The man must have a hard heart indeed, who can read unmoved the following touching little ballad:

“Poor John Brown and his three little Indian boys,

One was shot and one was drowned,

One was lost and never was found -

Poor John Brown and his three little Indian boys.”

Yankee Notions, Volume 5, Number 2, February 1856, page 60.

Ten Blackbirds

A decade before Septimus Winner published his song about the ten disappearing Indian boys, a children’s book included a song about ten disappearing blackbirds.

Ten little blackbirds sitting on a vine,

One flew away, and then there were nine.

Nine little blackbirds sitting on a gate,

One flew away, and then there were eight.

Eight little blackbirds flying up to heaven,

One flew away, and then there were seven.

Seven little blackbirds sitting on some sticks,

One flew away, and then there were six.

Six little blackbirds sitting on a hive,

One flew away, and then there were five.

Five little blackbirds sitting on a door,

One flew away, and then there were four.

Four little blackbirds sitting on a tree,

One flew away, and then there were three.

Three little blackbirds sitting on a shoe,

One flew away, and then there were two.

Two little blackbirds sitting on a stone,

One flew away, and then there was one.

One little blackbird sitting all alone,

He flew away, and then there was none.

Children’s Holidays: A Story Book for the Whole Year, New York, D. Appleton & Company, 1858, pages 23-25.

The song shares four rhyming word-pairs with Winner’s Injuns song; gate/eight, heaven/seven, door/four and alone/none. It shares three rhyming word-pairs with Frank Green’s N[-words] version; sticks/six, hive/five and alone/none.

It is not clear whether this song was original to the 1858 book in which it appears, but I did not find any earlier references to the song. There was, however, a traditional nursery rhyme

about two blackbirds sitting on a hill, which may have been a precursor to this song.

The Only True Mother Goose Melodies, Boston, J. S. Locke & Company, 1833, page 91.

This song was itself similar to another, perhaps earlier nursery rhyme, about two non-specific birds sitting on a stone, flying away one at a time.v

The Monthly Mirror (London), Volume 2, August 1796, page 250.

Grammer Gurton’s Garland: or, the Nursery Parnassus, a Choice Collection of Pretty Songs and Verses, London, R. Triphook, 1810, page 11.

There are several, later references to Ten Little Blackbirds. An alternate version appeared in 1876. Most of the verses are about different birds, with different methods of leaving, but the first verse is nearly identical, but with the blackbirds sitting on a “pine”

instead of a “vine.”

American Young Folks (Topeka, Kansas), March 1, 1876, page 6.

Ten Little Blackbirds was used in an ad campaign for hair-growth tonic, in which losing one’s hair was compared to birds

flying away.

Cosmopolitan (and numerous other newspapers and magazines) 1899.

Violin World, 1917.

The song was included in an elementary school English textbook in 1919, with blanks for students to fill in the appropriate verb for the number of birds left (nine “were”s and

one “was”).

A passing reference to the song compared falling autumn leaves to departing birds.

One by one the leaves are falling. “Ten little blackbirds sitting in a line.” The dropping off process has begun.

The Lexington Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), March 1, 1923, page 4.

A slightly altered version appeared in Nebraska in 1924.

Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), May 25, 1924, page 7C.

And in 1940, someone compared the countdown to Christmas with the old “jingle” about blackbirds flying away.

Each day the number will grow less, much like the old blackbirds-sitting-on-a-line jingle, until only one is left.

The Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama), November 26, 1940, page 8.

But regardless of how ancient the song is, or how well known or widespread, it appears that Septimus Winner may have been aware of the song when he wrote “Ten Little Injuns”

in about 1864.

Septimus Winner

By his own account, in a letter written in 1893, Septimus “Sep” Winner wrote his version of Ten Little Injuns “to amuse a children’s party” at his home in Philadelphia.vi His comment agrees

with an account that appeared in his hometown newspapers in 1877.

We all remember the delightful little ditty, unique in its absurdity - “Ten Little Injuns” - that he scribbled off for a family party at his house. Somebody suggested that he

publish it, and he laughed at the idea. But he did publish it, and millions have laughed at the drollery of it since.

Monongahela Valley Republican (Monongahela, Pennsylvania), September 20, 1877, page 1 (crediting the Philadelphia Press); Appleton Post (Appleton, Wisconsin), September 13, 1877, page 1 (crediting the Philadelphia Bulletin).

A biography written by someone with access to his diaries placed the date of the composition in 1864.

One afternoon during the hard days of the Civil War, in 1864 to be exact, Sep. Winner had a party at his home for the children of the neighborhood, and it was at this party that the youngsters

prevailed upon Mr. Winner to write a humorous song for them. This he consented to do, and in a very short time composed the piece he entitled Ten Little Injuns. It brought much merriment and broad smiles to the children present, which made Mr. Winner and everybody happy. His wife, and some of the parents of the children

present at the party, asked Winner to read it to them, which he did. They became rather enthusiastic about it and suggested that he publish it. This at first he refused to do as he considered it too childish, but finally

consented. It became very popular, and was sung for many years following.

Charles Eugene Claghorn, The Mocking Bird, The Life and Diary of Its Author, Sep. Winner, Philadelphia, The Magee Press, 1937, page 38.

The song may have been written in 1864, but all signs point to its being published for the first time in 1868.vii The New

York correspondent of a London newspaper, in a report dated February 10, 1868, mentioned the song was sung during a performance of the play, Under the Gaslight,viii in Septimus Winner’s hometown of Philadelphia.

Philadelphia. - Under the Gaslight now in the third week of performances at the Arch-Street Theatre, continues to draw immense houses

nightly. . . . Mr. Craig makes quite a character of Bermudas, and his song of the “Ten Little Injuns” is enthusiastically encored.

The Era (London, England), March 1, 1868, page 6.

Later that summer, a comment made in connection with the parody of the song based on President Grant’s rumored mixed-race children suggests that the original version of the song was

sung in New York at about the same time it was sung in Philadelphia.

Gen. Grant’s “love of little children” is being celebrated by his friends in the following significant lines. It is a parody on an old song which a prominent Radical friend

of ours will remember to have heard “performed” by the San Francisco Minstrels in New York last winter.

The Omaha Herald (Omaha, Nebraska), July 31, 1868, page 2.

The “San Francisco Minstrels” were performing in New York at the time, and had been there continuously for more than a year, so the reference to the performers is believable.

But the comment was ambiguous, in that it refers to it as a parody of an “old song,” not a new one. It may refer to the earlier Gibson family version of the song. And the lyrics of the Grant parody were more

similar to the Gibson version than the Winner chorus.

But the fact that it was being sung on stage in New York at about the same time Septimus Winner’s version was published, suggests the version referred to may have been the newer version,

even if they were mistaken about the lyrics of the chorus. The songs were, after all, similar, and may have been conflated by the listener or the writer.

The earliest reference to published sheet music for the song appeared in February 1868, a few weeks after the song was reportedly sung in Philadelphia. And the song was soon advertised

for sale in Vermontix and Massachusetts.x

Ten Little Injuns, comic song, sung as an encore by Master Shepard. Price 35c.

The Buffalo Commercial, February 25, 1868, page 2.

Rutland Daily Herald (Rutland, Vermont), March 27, 1868, page 3.

The July 1868 issue of a children’s magazine published the words and music of the song, with an attribution to Septimus Winner. The magazine, Our Schoolday Visitor, was published by Daughaday & Beeker of Philadelphia, Sep. Winner’s hometown.

Our Schoolday Visitor, for July, has been received, and is full of good things, in pictures, prose and poetry. . . . The contents

for July comprise the following:

. . . “Ten Little Injuns,” Funny Song and Chorus, with Piano or Organ accompaniment, by Sep Winner.

The Highland Weekly News (Hillsboro, Ohio), July 2, 1868, page 2.

The earliest version of the lyrics I have been able to find in online archives was apparently published in 1868. An annotation with the lyrics says it was published by Septimus’ brother

and former partner, Joseph E. Winner, who ran his own publishing house in the same city. The lyrics were printed in the first issue of the Singer’s Journal, a bi-weekly catalog of popular songs. Each issue included lyrics to about fifty songs, with an offer to send the sheet music to any of the songs for $0.40.

These early lyrics show that the chorus was different from the Gibson family version of 1849, and that it was likely based on “Ten Little Blackbirds,” which had appeared in print ten years earlier - it borrowed

the disappearing countdown format, and borrowed four rhyming word-pairs, gate/eight, heaven/seven, door/four and alone/none.

TEN LITTLE INJUNS.

Music published by J. E. Winner, 545 N. 8th St., Phil.

Ten little Injuns standing in a line,

One toddled home, and then there were nine.

Nine little Injuns swingin’ on a gate,

One tumbled off, and then there were eight - 1st Cho.

Eight little Injuns never heard of heaven,

One kicked the bucket, and then there were seven.

Seven little Injuns cutting up their tricks,’

One broke his neck, and then there were six. - 1st Cho.

Six little Injuns kicking all alive,

One went to bed, and then there were five.

Five little Injuns on a cellar door,

One tumbled in, and then there were four. - 1st Cho.

Four little Injuns out on a spree,

One dead drunk, and then there were three.

Three little Injuns out in a canoe,

One tumbled overboard and then there were two. - 1st Cho.

Two little Injuns foolin’ with a gun,

One shoots th’other, and then there was one.

One little Injun livin’ all alone,

He got married and then there were none. - 1st Cho.

One little Injun with his little wife,

Lived in a wigwam the balance of his life.

One daddy Injun, one mammy squaw,

Soon raised a family of ten Injuns more.

Henry De Marsan’s New Comic and Sentimental Singer’s Journal, New York, Number 1 [1868], page 6.

The verses count down the number of “Injun boys” from ten to one. All of them leave in one way or the other, some of them die, and some suffer an ambiguous result - leaving

the scene, but it’s not clear whether or how badly they might be hurt, or have just left the scene or otherwise been separated from the group.

One toddles home; one tumbles off a gate; one kicks the bucket; one broke his neck while “cutting up” tricks; one went to bed; one tumbled into a cellar; one was dead drunk;

one tumbled overboard while out in a canoe; one was shot (apparently by accident) while “foolin’ with a gun”; and the final one got married, after which he lived with his wife in a wigwam for the rest of

his life, and raised a family of “ten injuns more.”

The only one who is clearly dead is the one who “kicked the bucket.” The idiom, meaning to die, having been in use since at least the 1780s. Toddling home and being “dead

drunk” are not generally life threatening. Falling off a gate, tumbling into a cellar and falling out of a canoe could be dangerous, but not necessarily life threatening. Breaking one’s neck or being shot with

a gun seem like serious accidents, perhaps more dangerous at that time than they would be now, and could easily result in death. Going to bed isn’t particularly dangerous, but in context, where the lyric says they were

“all alive” and then “one went to bed,” might suggest that he died in his sleep. Not a good result, but not particularly gruesome.

The lyrics appeared in Henry De Marsan’s New Comic and Sentimental Singer’s Journal, published in New York City.

Henry De Marsan’s New Comic and Sentimental Singer’s Journal, New York, Number 33, page 225.

The periodical the lyrics appeared in, The Singer’s Journal, is available for viewing on the HathiTrust online archive. The issues are not dated on their face, but a careful reading of the covers of all sixty, available issues may give an idea of about when the first

issue came out.

The cover pages of most of the issues (1-4 and 22-60) state that they were published “fortnightly,” with some specifying every other Saturday. A few issues (Nos. 18-21) state

that they were being published weekly, and several issues (5-17) do not include any statement of the frequency of publication.

Also, the final eight issues (52-60) include advertisements for the publisher’s 1871 Valentines, which would be nearly two months of advertising for Valentines. During the previous

year, only five issues (or a little more than a month) had included advertisements for their 1870 Valentines. Assuming that fifty-six of the issues were published every other week, with four issues published weekly, the entire

run of sixty issues would have lasted 784 days. And further assuming that the final issue fell on Valentine’s day, 1871 at the very saltest, counting backwards from then would suggest a start date somewhere around December

20, 1868, at the very latest, although it is possible that it could have started slightly earlier. In any case, it seems likely the journal would have started publication in the second half (most likely the last quarter)

of 1868.

The lyrics printed in De Marsan’s Singer’s Journal are nearly identical to the lyrics printed in full sheet music published by Sep. Winner in 1868, the lone exception being what happened to one of the final three boys; instead of being “out in a canoe”

with “nothing for to do, One went to bed and then there were two.” The sheet music version is the earliest example I have seen of musical accompaniment for the song. The song was attributed to “Mark Mason,”

which is one of Septimus Winner’s several pseudonyms (other names he used include, Alice Hawthorne, Percy Guyer, Eastburn, Apsley Street, Marion Florence and Leon Dorexi).

Mark Mason (Sep. Winner pseudonym), Ten Little Injuns, Philadelphia, Sep. Winner & Co., 1868.xii

The chorus in both the Singer’s Journal and sheet music versions differs from the older Gibson family version. And since the Gibson family version is the version generally learned and sung today and over the past century, the version sung today is

not the one Septimus Winner wrote. The distinction may matter to people who do not want to sing a song “based on” or “derived from” a racist song, because if they sing the Gibson family version, they

are not singing such a song. The Septimus Winner version, which disappears and kills off its protagonists, is not the version known and sung today. It did, however, inspire another racist version - one based on the same

melody, but replacing the protagonists with a different ethnic group and a more problematic name.

Frank Green

George Washington “Pony” Moore of the Christy Minstrels blackface troupe introduced a new version of the song in St. James Hall, London, England in August 1868.

In the present entertainment, Mr. Moore’s opportunities lie in a new comic song, entitled “Ten little N[-words],” which is uproariously successful . . . .

The Weekly Dispatch (London), August 30, 1868, page 10.

The song was still popular months later.

The Christy Minstrels are in full feather just now at St. James’s Hall, and appear to be making mints of money. Mr. Joe Brown’s dancing, Mr. Wallace’s lecture on Anatomy,

and Mr. Moore’s “Ten Little N[-words],” are the most noticeable features in the lively part of the entertainment.

Echoes, No. 1, January 9, 1869, page 12.

Hopwood & Crew published the sheet music; “written by Frank Green” with “music by Mark Mason” (Winnerxiii).

Frank W. Green was an English song writer and playwright, responsible for such ditties as, “Dolly Varden” and “The Snow is on the Hills,” and for the stage plays, Dumb Belles of Fairyland, Cinderella

in Quite Another Pair of Shoes (a “burlesque”), Hearts of Oak; or the Middy Ashore (a “nautical extravaganza”) and “Carrot and Parsnip; or, The King, the Tailor, and the Mischievous F.”

(an “extravaganza”).

The cover art includes an image of Moore in blackface and cartoons illustrating the ten verses. I have only seen the cover page of the sheet music, but the images appear to match (with

one exception) lyrics later published in the United States in issue number 20 of De Marsan’s Singer’s Journal. The image for eight does not match the lyrics as printed in the Singer’s Journal. However, its does seem to match the original “Injun” lyrics, in which eight little boys had “never heard of heaven,” and one boy “kicked the bucket,” leaving seven. The

difference may reflect the differences between England’s experience in Africa, where Christianity was not widespread, and the United States where it was widespread among African-Americans.

The methods of disappearance and death in Frank Green’s version are even more ludicrous and violent than those in Winner’s “Little Injun” version. The lyrics illustrated

in the cover page artwork are reminiscent of the dark humor of Edward Gorey’s popular Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963); “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs,” “B is for Basil assaulted by bears,” “L is for Leo who swallowed some tacks,” “M is for Maud who was swept out to sea”

and “Z is for Zillah who drank too much gin.” But like the earlier, “Injun” version, Frank Green’s N[-word] version ends on an optimistic note; the one who got married lives “all his days

a happy little life,” along with his wife; they dwell by the shore and “soon raised a family of ten.”

In addition to the disappearing countdown format Green copied from Winner, Green appears to have borrowed rhyming word-pairs from “Ten Little Blackbirds,” sticks/six, hive/five

and alone/none.

Henry De marsan’s New Comic and Sentimental Singer’s Journal, New York, Number 20 [1868 or 1869]xiv, page 126.

Ten went out to dine, “one choked his little self,” leaving nine.

Nine cried at his fate, while “one cried himself away,” leaving eight.

Eight slept until eleven, “one over slept himself,” leaving seven.

Seven cut up sticks, while “one chopped himself in halves,” leaving six.

Six played with a hive, and “a bumble bee killed one,” leaving five.

Five went in for law, but “one got in chancery,” after which there were four.

Four went out to sea, “a red herring swallowed one,” leaving three.

Three walked in the zoo, but “a big bear cuddled one,” leaving just two.

Two sat in the sun, but “one got frizzled up,” leaving just the one.

One got marred, after which there were none.

The one who got married lives “all his days a happy little life,” along with his wife; they dwell by the shore and “soon raised a family of ten” more.

The Christy Minstrels were still singing the song in England years later, when they insinuated themselves into a libel suit involving a London wine merchant and a line in a novel about bad

wine.

Gilby, a London wine merchant, whose beverages enjoyed the distinction of being abused in Rhoda Broughton’s last novel, on account of which he obliged her to omit several pages from

the first edition,xv has been craftily defied by Christy’s Minstrels. One of their number sang -

Ten little n[-words] drinking sherry wine,

One drank -

[Here another held up a placard with the single word “Gilby’s” on it, and the singer went on)

then there were nine.

Gilby was furious, but his lawyers told him he could do nothing, for neither of the minstrels had uttered a complete libel.

Boston Evening Transcript, January 1, 1877, page 8.

Several months after the debut of the song in 1868, an even more macabre version of the song (if that’s possible) was sung in a Christmas pantomime of Robinson Crusoe, first performed at the Covent Garden Theatre, December 26, 1868. The song detailed the various ways the King of the Cannibals ate nine of ten little children -

the last one was “but skin and bone,” so they kept him and fed him, “until he’s fatter grown.”xvi

Ten little n[-words], looking bery fine,

De king he gobbled one of ‘em, den dere was nine,

Nine little n[-words] - dreadful was their fate,

De king he eat another one, den dere was eight.

Eight little blackymoors couldn’t spell eleven,

De King make one a sandwich, den dere was seven.

Seven little blackymoors studied poli-tics,

De King thought one looked berry nice, and soon dere was six.

Six little n[-words] looking all alive,

One looked so berry plump dat soon dere was five.

Five little pickaninnies looking berry raw,

De King cooked one to cure him, den dere was four.

Four little ne-ger-roes hunting for a flea,

One ob em cotched it, den dere was three.

Three little innocents playing with de flue,

One flew down him monarch throat, den dere was two.

Two little n[-word]sizzies, thought they’d cut and run,

Berry soon I caught ‘em up - den dere was one.

One little n[-word], he was nought but skin and bone,

So we’re keeping him and feeding him, until he’s fatter grown.

Act 1, Scene 8, Henry J. Byron, Robinson Crusoe; or, Friday and the Fairies!, London, J. Miles and Co., 1869.

“The music of the several airs and melodies in the pantomime published by Messrs. Hopwood & Crew,” the same publishers who published Frank Green’s version. The chorus

between the verses, however, were completely different. This version doesn’t seem to have ever caught on.

But Frank Green’s version did catch on, particularly in England, where it remained the dominant version of the song. His version was not unknown in the United States, but (based on

the frequency of results in online archives) the Indian version remained much more common in the United States; perhaps because the Gibson family version was introduced in the United States and known for decades before Frank

Green’s version was written and introduced in England.

The predominance of the Indian version in the United States may also have been the result of a a more widespread sensitivity and aversion to the use of the N-word. A comment in a review

of a children’s picture book sold in the United States in 1873 may illustrate the point. The book was based on Frank Green’s lyrics, yet the reviewer replaced the N-word with “black boys,” “so

as not to hurt anybody’s feelings.”

I don’t know when I’ve laughed inwardly more than I did at a book that a dear little girl had in our meadow yesterday. The pictures are enough to split the sides of the soberest

Jack-in-the-Pulpit that ever lived; so funny, and so bright with color that, for a moment, it seemed to me as if the autumn landscape had suddenly turned into a great big illuminated joke. The book is English -I’d wager

my stalk on that; but it is republished by Mr. Scribner’s publishing house in New York. It is called “The Ten Little N[-words];” and I’ll tell you the thrilling story it illustrates, if you’ll

allow me to change one little word throughout the poem, so as not to hurt anybody’s feelings:

St. Nicholas, Volume 1, Number 2, December 1873, page 101.

The Atlantic divide of the predominant ethnicity of the counted boys continued decades later, with the publication of an Agatha Christie crime novel. Its title was “Ten Little N[-words]”

when released in England in late-1939, but “And Then There Were None” when released in the United States in early 1940. A stage version of the book went under its original UK title in England in 1943, but opened

as “Ten Little Indians” on Broadway in 1944.

Ten characters in her book die off, one-by-one, in ways similar to those described in Frank Green’s song, with a couple differences; the one who “cried himself away” when

there were nine left was replaced by the one who “overslept himself” with eight left in the earlier version, and the one who overslept was replaced by one who stayed in Devon while eight were “traveling

in Devon,” leaving seven. I guess oversleeping and crying one’s self to death don’t make for a very suspenseful story. The other differences is with the final boy, who instead of getting married and raising

ten children, hangs himself - “and then there were none.”

The “traveling in Devon” verse was not original to Christie in 1939. It was in the children’s book published in 1873, as described in St. Nicholas children’s magazine. It’s not clear who added that lyric or when, although the place of Devon suggests a British origin.

The St. Nicholas reviewer said the book they saw as published by “Scribner’s.” McLoughlin Brothers also published

a similar, full color children’s book based on the song at about the same time.

“The Ten Little N[-words].”

The above is the title of an exceedingly attractive little picture book for children, published by McLaughlin Bros., of New York. The story is told in rhyme, set to smile easy going music,

and the colored wood cuts are both humorously and carefully done. The “Rebus A B C” is another book of similar nature, published by the same firm.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 4, 1874, page 4.

Books of the same title, but not specified as to whether McLoughlin’s or Scribner’s, appear in advertisements from Vermont to Iowa, and presumably other points in between and

beyond.

The Woodstock Post (Woodstock, Vermont), February 27, 1874, page 4.

The Muscatine Journal (Muscatine, Iowa), December 16, 1874, page 4.

Reading Times (Reading, Pennsylvania), February 12, 1875, page 2.

I have not seen a copy of either the Scribner’s (1873) or the McLoughlin Brothers (1874) books, and am not sure whether Scribner’s actually published such a book, or the reviewer

misstated the publisher. There is, however, an undated color image bearing the McLoughlin Brothers name. The image is available in the Wikicommons, mislabeled (I believe) as a picture book written by Frank Green in 1869.xvii

Although the rest of the 1874 book is unavailable, there is a full copy of the same story published by McLoughlin Bros. twenty years later. The cover was different, so the rest of the artwork

may be new as well, but it may give some sense of what what the 1874 (or 1873) original may have looked like. The words are nearly identical to the ones paraphrased in the St. Nicholas review of 1873. The major change was the switch from chancery court to a criminal court when counting from five to four; chancery courts are a thing in Britain, and

not the United States, so it may have been a change intended for an American audience. The book also included sheet music with Septimus Winner’s melody.

Front and Back Covers

“One choked his little self”

“ One overslept himself” and “One got left [in Devon]”

“One chopped himself in halves” and “A Bumble-Bee stung one”

“One got in prison” and “A Red Herring swallowed one”

“The big Bear hugged one” and “One got frizzled up” in the sun.

One “got married, and then there were none.”

One “Lived many years a happy little life.”

Summary

The simple, counting-rhyme “Ten Little Indians” learned by most young American children is nearly identical to a song published and sung in the United States by the Gibson Family

Troupe of singers in 1849, under the title, “Old John Brown.” It appears to have been an elaboration on an earlier, traditional English nursery rhyme, “Tom Brown’s Two Little Indians.”

Septimus Winner wrote and published a now-problematic, similar song, in the United States in 1864, which he published in early-1868, as “Ten Little Injuns.” His song has ten

verses, in which nine of ten “Injun boys” disappear or die off, one-by-one. And his chorus is not the same song as written by the Gibsons and still sung today. Winner’s chorus has a different melody and

the words count from one to five and six to ten, instead of one to three, four to six, seven to nine, and ending at ten.

Frank Green adapted Winner’s music to new lyrics in England in the second half of 1868. His new lyrics were about “Ten Little N[-word] Boys,” and introduced nine new methods

of disappearance or death. Greens version was later published in the United States and adapted into children’s picture books.

Both Green’s and Winner’s verses appear to have been based on a song published a decade earlier, “Ten Little Blackbirds,” in which ten blackbirds disappear in a variety

of ways. Between the two of them, Green’s and Winner’s lyrics share no fewer than six rhyming word-pairs with the earlier, blackbirds song. “Ten Little Blackbirds” may have been influenced by earlier

nursery rhymes about “two little blackbirds sitting on a hill” and/or “two birds sitting on a stone.”

Interestingly, this brief, early ancestor of Winner’s and Green’s problematic versions of the song includes (essentially) the final line of those songs; the line used as the

title of the American release of mystery novel Christie wrote based on Green’s lyrics, and of the US release of Rene Clair’s 1945 film adaptation of the book.

And Then There Were None.

The Monthly Mirror (London), Volume 2, August 1796, page 250.

|

Kinderlieder aus Sachsen, Leipzig, G. Schoenfeld, 1905, page 10.

|

i https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015096611119&view=1up&seq=1&skin=2021

ii http://historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/holmes-william-1779-1851

iii http://historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/dawson-george-1790-1856

iv https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/13371?show=full

v For more background on this rhyme, see my earlier post, Birds, Bottles and Flies - the Early History of “Ninety-Nine Bottles of Beer on the Wall,” https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2022/11/birds-bottles-and-flies-early-history.html

vi St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 2, 1894, page 36 (a letter by Sep Winner, from a collection of letters

solicited by a neophyte songwriter from experienced songwriters, requesting information on the origin of popular songs)..

vii The March 1868 date of earliest performance is consistent with the twenty-eight-year copyright renewal date for the song in the

United States, notice of which was published in April 1896. Musical Record, Number 411, April 1896, page 18 (“The following-named musical works have been re-entered for copyright before the expiration of their first

term of twenty-eight years, and Certificates of such re-entries have been given by A. R. Spofford, Librarian of Congress. . . . Ten Little Injuns, Song and Chorus, By Sep. Winner . . . .”).

viii The play, Under the Gaslight, is also historically significant as the play that introduced

the trope of a protagonist-in-distress being tied to a railroad track and rescued by an heroic protagonist. Interestingly, in the original and many of the early copycat scenes, the hero was a heroine and the person in distress

a man. See my earlier post, Snorkeys, Red Caps and Railroad Tracks - a Melodramatic History of Amputee Baseball and the Tied-to-the-tracks

Trope. https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2021/04/snorkeys-red-caps-and-railroad-tracks.html

ix Rutland Daily Herald (Rutland, Vermont), March 27, 1868, page 3.

x Fall River Daily Evening News (Fall River, Massachusetts), June 8, 1868, page 3.

xi Charles Eugene Claghorn, The Mocking Bird, The Life and Diary of Its Author, Sep. Winner, Philadelphia, The Magee Press, 1937, pages 61-35 (“A list, though incomplete, of the songs by Mr. Winner, together with the names

he used in publishing them . . . follows: . . . .”); The Philadelphia Times, May 16, 1899, page 6 (“’The Mocking Bird’ and ‘What is Home Without a Mother’

were written under the nom de plume of Alice Hawthorne . . . . He also had as noms de plume, ‘Marion Florence,’ ‘Percy Guyer,’ ‘Leone Dore’ and ‘Apsley Street’ . . . .”).

xii https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015096611119&view=1up&seq=1&skin=2021

xiii The Musical Record, Number 425, June 1897, page 33 (“The following-named musical works

have been re-entered for copyright before the expiration of their first term of twenty-eight years, and Certificates of such re-entries have been given by A. R. Spofford, Librarian of Congress. . . . Ten Little N[-words].

Words by Frank Green. Music by S. Winner. . . . Oliver Ditson Company.”).

xiv The Singer’s Journals are undated, although the catalogue record on HathiTrust online archive dates the sixty issues, numbered

1-60 as dating from 1868 through 1882. An annotation on the cover of the first four issues suggest it is “fortnightly” or once every two weeks. Numbers 5-17 do not state a frequency. Issues 18 through 21 state

weekly. Thereafter, “fortnightly” again. If, as argued above, Number 1 was published in about November or December 1868, Number 20 would have been published about nine or ten months later, or about August-October

1869.

xv Compare, “I think he is quite capable of poisoning us with Gilbey’s champagne and grocers’ sherry” (Rhoda Broughton,

Joan, Volume III, London, Richard Bentley and Son, 1876, page 225), with, “I think he is quite capable of poisoning us with bad champagne and acid sherry” ((Rhoda Broughton, Joan, London, Richard Bentley and Son, 1877, page 386).

xvi Robinson Crusoe pantomimes and other “King of the Cannibal Island” pantomimes, plays

and musical comedies were standard fare in British theaters during the Christmas season during the 1800s. The song was sung by a character named Hokypokywankyfum, a stock character those types of shows. The name of the character

was derived from the original “King of the Cannibal Island” lyrics in the 1820s, which may be the origin of the expression “Hokey Pokey.” The expression may have been influenced by the name of a Hawaiian

diplomat and Governor of Oahu, Poki, who accompanied King Kamehameha II during his trip to London a few years before the song became popular. See my earlier post, “Hokey Pokey” and Madame Boki - Hawaiian Royalty

and the History and Origin of “Hokey Pokey,” (https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2022/04/hokey-pokey-and-madame-boki-hawaiian.html).

xvii https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frank_Green_TLN_1869.jpg

.jpg)

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

.JPEG)

%20ten.JPEG)