The History of the Unicycle

Who invented the Unicycle? And

when?

Good question.

The History of the Unicycle

It is widely presumed that the

unicycle was invented by someone who removed the rear wheel from an

old-fashioned “ordinary” or “penny-farthing” bicycle (the one with the with a

large front wheel and small rear wheel).

The suggestion is plausible. There were, in fact, riders who reportedly

converted two-wheelers into one-wheelers by removing the rear tire:

Mr.

O. H. Whetmore, the champion amateur fancy bicycle rider of the country . . .

does feats which appear incredible, until they are actually accomplished before

the eyes of every one. In the parade he

removes the small wheel from his bicycle, and presents the singular spectacle

of a man ambling along, mounted on top of a big wheel.

The Springfield Globe-Republican (Springfield, Ohio), June 21,

1885, page 5.

Other sources note that Alfredo

Giovanni Battista Scuri of Turin, Italy (variously described as a gymnastics

coach[i]

or circus performer[ii] -

perhaps both) received an early patent on a unicycle. Legend has it that Scuri “invented” his unicycle

when his bicycle broke in half during a performance; he completed the show on

one wheel; Eureka! [iii] Whether the story is true or not, the express

language of his patent suggests that there was already a whole “class of

velocipedes” with one wheel, even before he received his patent:

My

invention relates to improvements in that class of velocipedes called “monocycles,”

in which one wheel is employed, that serves both as a propelling and steering

wheel. . . .

G. Battista Scuri, US Patent

242,161, May 31, 1881 (filed April 7, 1881).

And, in any case, the earliest

images of unicycles appeared more than twelve years earlier:

|

| Scientific American, Volume 20, Number 7, February 3, 1869, page 101. |

If anyone deserves specific

credit, by name, for “inventing” the unicycle, it may be Frederick Myers, of

New York City. He received the earliest known patent on a unicycle on March 2,

1869; just a few weeks after a unicycle appeared in Scientific American. Patents at the time were not

marked with the filing date, so it is difficult to determine when the patent

was filed, or when he conceived his unicycle; but it seems likely that it could

have been before the earlier image from February:

My

invention is designed to provide a velocipede capable of supporting a rider

upon one wheel, and being propelled by the power of the rider, applied to the

axle of the said wheel by his feet, through the medium of a treadle-mechanism,

the rider being supported on a saddle, at or near the top of the wheel, in a

manner similar to that of the two-wheel velocipedes now in use.

F. Myers, US Patent 87,355, March

2, 1869.

Although his patent is the

earliest, Myers was not the only person working on one-wheeled velocipedes; and it is not clear that Myers’ design was

the first unicycle. His design appears fairly complex; not at all like the

simple concept of a seat, pedals and a wheel one might expect from the first of its kind.

Scientific American described the "one-wheeled velocipede" as "an English invention," but without naming an inventor. The unicycle illustrated in its February 13, 1869 issue (shown above), looks more-or-less like a modern unicycle; but with a twelve-foot diameter (nearly four meters) wheel and pedals with "stilts," enabling a rider to pedal the gigantic wheel. With a large wheel, and cadence of 50 revolutions per minute, the inventor expected the contraption to reach speeds of up to twenty-five miles per hour. Presumably, this large-wheeled, stilt-pedal unicycle was a modification of an earlier, simpler model.

By the end of 1869, the United States patent office had issued more than a dozen patents for various kinds of one-wheeled unicycles or monocycles.

Scientific American described the "one-wheeled velocipede" as "an English invention," but without naming an inventor. The unicycle illustrated in its February 13, 1869 issue (shown above), looks more-or-less like a modern unicycle; but with a twelve-foot diameter (nearly four meters) wheel and pedals with "stilts," enabling a rider to pedal the gigantic wheel. With a large wheel, and cadence of 50 revolutions per minute, the inventor expected the contraption to reach speeds of up to twenty-five miles per hour. Presumably, this large-wheeled, stilt-pedal unicycle was a modification of an earlier, simpler model.

By the end of 1869, the United States patent office had issued more than a dozen patents for various kinds of one-wheeled unicycles or monocycles.

In any case, the physics of

bicycles focused the attention of engineers on two likely avenues of progress;

a larger front wheel, and fewer wheels. In

the late 1860s, velocipede pedals were generally direct-drive pedals; attached

to the hub of the front wheel, with no gearing and no chain drive. A larger front tire promised higher speeds; and

using fewer wheels promised less friction and greater efficiency:

Undoubtedly

the fewer the mechanical appliances interposed between the power and the

proposed result – the force exerted and the force delivered – the more

satisfactory will be product of the two elements. This theory is specially applicable to the

velocipede. Four-wheeled vehicles

propelled by the physical power of the rider are old; the three-wheeled

carriage is more modern; the two-wheeled vehicle, now so popular, may perhaps

be compelled to make way for the one-wheeled contrivance; and surely this

latter is bringing the theory of wheel-riding to its ultimate – perhaps

carrying it beyond its proper limit.

Scientific American, Volume 20 (n.s.), Number 14, April 3, 1869,

page 221.

The same article suggests that both

unicycles and high-wheeled “ordinaries” were already in existence. In the article, “Soule’s

Simultaneous-Movement Velocipede,” which looked, more or less, like a modified

“penny-farthing,” was described as, “in effect a unicycle”:

The

machine shown in the accompanying engraving is, in effect, a unicycle, the

small following wheel being only one point of suspension for the reach, and

acting only as a truck or friction wheel. . . .

The reach supporting the seat is hinged to the lower end of an upright

pivot secured in a yoke at the top of the forked brace, the lower end of which

are boxes for the reception of the ends of the driving-wheel axle. This arrangement allows the wheel to be

guided to the right or left, and also to be projected under the seat of the

rider, or further in front. By this

arrangement, when great speed is desired and the state of the rode will permit,

the rider may bring the wheel directly under him, and in descending grades he

can project it in front to guard against the danger of being thrown over.

Scientific American, Volume 20 (n.s.), Number 14, April 3, 1869,

page 221.

The caption of a picture of a velocipede published in January, 1869, suggests that one-wheeled velocipedes were one of many types of velocipedes with anywhere from one to four wheels:

|

| The Plymouth Weekly Democrat (Plymouth, Indiana), January 28, 1869, page 4. |

Further evidence that the concept

of a unicycle, if not actual unicycles, may have been fully developed and

well-known before 1869 comes from an unlikely source; a book of comic poetry

published in 1869 (apparently in January 1869).

The book includes two poems, written in a mock-German-American dialect;

both poems are about unicycles; and the illustrations show the familiar form of a simple unicycle:

Herr

Schnitzerl make a philosopede,

Von of de pullyest kind;

It

vent mitout a vheel in front,

Und hadn’t none pehind.

Von

vheel vas in de mittel, dough,

Und it vent as shure ash ecks,

For

he shtraddled on de axel dree

Mit der vheel petween his lecks.

Charles G. Leland, Illustrations

by Frank Beard, Hans Breitmann und His

Philosopede, New York, Jesse Haney, 1869. [iv]

But which was first? We may never

know. The “ordinary” or “penny farthing”

was certainly more successful. High-wheeled

bicycles dominated the market into the 1880s, when chain-drive “safety” made riding

safer, easier, and more accessible.

Although unicycles are known to have existed since as early as 1869, the

first indication of their widespread use is in the mid-1880s.

|

| Memphis Daily Appeal (Tennessee), April 22, 1869. |

Unicycle Exhibitions

In October of 1884, for example, the

Capital Bicycle Club of Washington DC held a bicycle tournament:

Messrs. Dinwiddie and Seely then gave

a wonderful and thrilling exhibition of skill and courage in the management of

the “monocycle.” The exhibition was a

novel one, unsurpassed perhaps in the world, and called forth enthusiastic

applause.

The Evening Critic (Washington DC), October 18, 1884, page 4.

In the spring of the 1884,

Professor W. D. Wilmot, of Boston, Massachusetts, toured the American West,

giving exhibitions in from Omaha, Nebraska, to Bozeman Montana, Fargo, North

Dakota and Minneapolis, Minnesota, and presumable places in between.

In Omaha:

An old lady remarked: “If I had not

seen it with my own eyes, I would not have believed it; but there goes a wheel

running away with a man.” This fact was

demonstrated last evening by Mr. Wilmot removing the saddle, backbone and small

wheel, and riding the large wheel, or monocycle, around the rink. Mr. Wilmot wears a medal given to the

champion bicycle rider of the world.

Omaha Daily Bee, March 17, 1884, page 5.

In Montana:

The skating amphitheatre was crowded

last night to witness the performance of Prof. Wilmot on the bicycle. . .

. The feats performed were simply

remarkable, chief among which was the riding of the single wheel, and that

without any seat.

The skating amphitheatre was crowded

last night to witness the performance of Prof. Wilmot on the bicycle. . .

. The feats performed were simply

remarkable, chief among which was the riding of the single wheel, and that

without any seat.

The Bozeman Weekly Chronicle (Montana), May 7, 1884, page 3.

More than 500 people turn out nights

at Helena to witness the wonderful feats of Prof. Wilmot on the monocycle and

the byccicle race with Armitage. A mile

was made in 3:51.

St. Paul Daily Globe (St. Paul, Minnesota), May 8, 1884, page 2.

In North Dakota:

Wilmot exhibition in Bismark. The highlight was riding the “single wheel or

monocycle, made by running the rear wheel, back-bone and saddle, and thus

riding around the rink as, as has been aptly said, ‘without visible means of

support.’ Prof., Wilmot is indeed “a cuss on wheels” and has a just claim to

the championship in bicycle riding as far as heard from.”

Bismarck Tribune, May 16, 1884, page 8.

The spate of unicycle exhibitions

in the United States followed on the heels of exhibitions given in Europe one

year earlier:

Mr. Sari of Milan [(is “Sari”

the same person as “Scuri” who received a patent in 1891?)] is said to be a skillful monocycle

rider. He astonished a select circle of

amateur riders in Paris recently with an exhibition of surprising feats. Several Parisian riders have endeavored to

obtain a mastery of the monocycle, but only one has succeeded in any marked

degree, and there is said to be only one skilful rider in England.

The Sun (New York), January 28, 1883, page 6.

Although unicycle riders

astounded the crowds in the early 1880s, unicycles actually date to the dawn of

modern cycling, in 1869.

1869 – the Dawn of Modern Cycling

The first indication of the

existence of unicycles follows close behind the first, successful two-wheeled

“velocipedes.” A German Baron named Drai

invented a two-wheeled laufmaschine

(literally, “running machine”), or “Draisine,” in about 1817. The Draisine was operated by running on the

ground and coasting (imagine a caveman

motorcycle or child’s

Like-a-Bike). At some point during

the early 1860s, someone (most likely a Frenchman named Lallement; although that is under dispute) attached

foot-pedals and a crank to the front wheel of an old Draisine, resulting in the

first pedal-powered bicycle.[v] Lallement received a patent for his invention

in 1866. By 1869, there was a full-on

bicycle craze in the United States.

But it all started in France:

Improvement

in the Velocipede.

Within a few months the vehicle

known as the velocipede has received an unusual degree of attention, especially

in Paris, it having become in that city a very fashionable and favorite means of

locomotion. To be sure the rider “works

his passage,” but the labor is less than that of walking, the time required to

traverse a certain distance is not so much, while the exercise of the muscles

is as healthful and invigorating. A few

years ago, these vehicles were used merely as playthings for children, and it

is only lately that their capabilities have been understood and

acknowledged. Practice with these

machines has been carried so far that offers of competitive trials of speed

between them and horses on the race course have been made.

Scientific American, Volume 19 (n.s.), Number 8, August 19, 1868,

page 120.

Although the bicycle was relatively

new in 1869, it had already been used and improved. The Hanlon Brothers, a well-known acrobatic

troupe, received their first bicycle-related patent in July of 1868, for an

improved seat and adjustable crank:

|

| Scientific American, Volume 19 (n.s.), Number 8, August 19, 1868, page 120. |

A number of other "improvements" never quite caught on:

|

| Scientific American, June 12, 1869. |

|

| Scientific American, May 29, 1869, page 337. |

|

| Scientific American, March 6, 1869 - Ice Bike. |

|

| Scientific American, March 6, 1869. |

|

| Scientific American, April 10, 1869, page 228 - a bicycle built for two. |

One-Wheeled Velocipedes

The velocipede craze motivated

numerous engineers to look for the next big thing. Many of their proposals required only one

wheel. Many of these unicycles, often called “monocycles,” had the rider sitting inside the

wheel. Several of the designs look

pretty cool; but I imagine none of them worked very well (this motorized

one might be more practical).

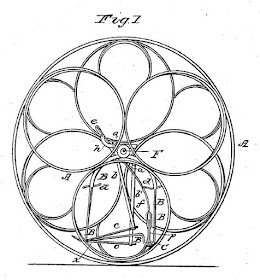

My favorite one of the lot is

Hemmings’ “Unicycle or Flying Yankee Velocipede,” which was featured in

Scientific American in March of 1869:

Several others also looked pretty

interesting:

One-wheeled, sit-on-top unicycles

are even older than the earliest sit-inside models. The earliest I have found is a proposed design from from England, in

February 1869:

|

| The Sun (New York), February 4, 1869. |

Two days later, a newspaper reported that:

A man in Dayton, Ohio, has invented

a velocipede with one wheel. The only

fault found with it is that it can’t be made to go.

Vermont Daily Transcript, February 6, 1869, page 2.

The article, however, is silent

on whether it was a sit-on-top or sit-inside unicycle. In any case, it doesn’t seem to have worked

very well. But others were also working

on one-wheeled machines.

Frederick Myers received his

patent on March 2, 1869. Thomas Ward,

also of New York City, received a patent on April 6, 1869. Ward’s unicycle looked more like a modern

unicycle; and the text of the patent suggested that such one-wheeled

velocipedes were already known:

The invention relates to certain

improvement on that class of one-wheeled velocipedes in which the driver’s seat

is arranged above the wheel, it being pivoted to the axle of the same.

Thomas W. Ward, US Patent 88,683,

April 6, 1869.

But the question remains; did these

innovators modify a pre-existing “ordinary,” or did they jump straight to a

unicycle, in order to reduce friction and increase efficiency. The answer depends on when such high-wheeled

bicycles, themselves, were invented.

Unicycles were known to exist, or at least the concept of a unicycle

existed, as early as February, and perhaps January, of 1869; and likely

earlier. So, when was the high-wheeled

“ordinary” invented?

Most sources credit Eugene Meyer

of France with inventing high-wheeled bicycles in 1869. Meyer received a patent on individually adjustable wire spokes in August 1869, which made large wheels lighter, stronger and more practical:

David V. Herlihy, Bicycle: the History, Yale University Press, 1869.

Although makers had understood all

along that larger wheels would improve gearing and enhance speed, they found

that wooden wheels simply could not be safely constructed beyond about forty

inches in diameter.

The picture of “Soule’s Improved Velocipede,” for example, showed a high wheel in April of 1869. Although Soule reportedly claimed that his design had, “advantages over the ordinary two-wheeled

vehicle,” it is not clear whether “ordinary,” in that context, referred to earlier high-wheeled bicycles, or to any earlier two-wheeler.

The concept of unicycles (if not actual unicycles) predates Eugene Meyer's wire-spoke patent by at least six months. And, at least one fictional, if not functional, unicycle even predates Frederick Myer's early unicycle patent. Illustrations of the fictional unicycle show a fully-realized, simple design.

The concept of unicycles (if not actual unicycles) predates Eugene Meyer's wire-spoke patent by at least six months. And, at least one fictional, if not functional, unicycle even predates Frederick Myer's early unicycle patent. Illustrations of the fictional unicycle show a fully-realized, simple design.

Hans Breitmann’s Philosopede

Among modern-day “Witches,” or

practitioners of the Wiccan religion, Charles G. Leland is a sort of

prophet. In 1899, he published one of

Wicca’s standard texts, Aradia, or the

Gospel of the Witches. He gathered

the material for the book from a “witch informant” in Italy, where he had lived

since 1888. But long before he moved to

Italy and became a devotee of Stregheria,

he was a famous writer; famous mostly for his Hans Breitmann Ballads; stories and verse written in a mock German-American

dialect.

The first of the Hans Breitmann ballads Hans Breitmann's Bardy (Party), was published in about 1857. His first collection of ballads, Hans Breitmann's Party, with Other Ballads, came out more than a decade later, 1868. The collection appears to have been a success. His second collection of verses, Hans Breitmann's Christmas, which was available for purchase as early as May 1869, included Schnitzerl's Philosopede, in two parts, without illustrations. The two parts included a brief prologue (Brolock!) and a longer poem, Hans Breitmann and His Philosopede.

The prologue appeared at least as early as February 12, 1869; and appeared in numerous newspapers and periodicals during the following months. Scientific American published the prologue, as Hans Breitmann's Shtory About Schnitzerl's Philosopede, crediting the New York Sun. Although the New York Sun from that period is available for online search, I have been unable to determine the date on which it appeared in The Sun. The Sun, coincidentally (or not?), is also the newspaper that printed Scientific American's image of a one-wheeled velocipede more than a week before the date of the issue in which it appeared in Scientific American (did Scientific American release their issues before their nominal publication date; or had they shared the image with The Sun before release?). The editor of The Sun is mentioned by name in the closing lines of Part II of the poem; perhaps suggesting some connection.

At some point, Parts I and II were published together, in one volume with illustrations, as Hans Breitmann und His Philosopede. It is not apparent whether both parts were published together before the prologue was widely published on its own, or whether Part II was added later, and published later. Although the title page of the book simply lists the year of publication, 1869, an advertisement located near the back of the book suggests that the book may have been published as early as January, 1869:

The first of the Hans Breitmann ballads Hans Breitmann's Bardy (Party), was published in about 1857. His first collection of ballads, Hans Breitmann's Party, with Other Ballads, came out more than a decade later, 1868. The collection appears to have been a success. His second collection of verses, Hans Breitmann's Christmas, which was available for purchase as early as May 1869, included Schnitzerl's Philosopede, in two parts, without illustrations. The two parts included a brief prologue (Brolock!) and a longer poem, Hans Breitmann and His Philosopede.

The prologue appeared at least as early as February 12, 1869; and appeared in numerous newspapers and periodicals during the following months. Scientific American published the prologue, as Hans Breitmann's Shtory About Schnitzerl's Philosopede, crediting the New York Sun. Although the New York Sun from that period is available for online search, I have been unable to determine the date on which it appeared in The Sun. The Sun, coincidentally (or not?), is also the newspaper that printed Scientific American's image of a one-wheeled velocipede more than a week before the date of the issue in which it appeared in Scientific American (did Scientific American release their issues before their nominal publication date; or had they shared the image with The Sun before release?). The editor of The Sun is mentioned by name in the closing lines of Part II of the poem; perhaps suggesting some connection.

At some point, Parts I and II were published together, in one volume with illustrations, as Hans Breitmann und His Philosopede. It is not apparent whether both parts were published together before the prologue was widely published on its own, or whether Part II was added later, and published later. Although the title page of the book simply lists the year of publication, 1869, an advertisement located near the back of the book suggests that the book may have been published as early as January, 1869:

The extensive circulation and great

popularity which Haney’s Journal has attained, and the general desire of our

readers, encourage us to announce that, with the January No., 1869, it will be

Enlarged to DOUBLE its present size . . . .

The same advertisement appears in a separate book published in 1868, and in a a magazine dated in October 1868; consistent with a book published in early 1869.

If the book actually was published in January 1869, the concept of a unicycle (if not actual unicycles), dates to the beginning of 1869, if not earlier. If the "ordinary" was invented any time after January 1869, the concept of a unicycle may actually precede the "ordinary".

If the book actually was published in January 1869, the concept of a unicycle (if not actual unicycles), dates to the beginning of 1869, if not earlier. If the "ordinary" was invented any time after January 1869, the concept of a unicycle may actually precede the "ordinary".

The book is a work of art, so it

is difficult to judge whether it is a case of art imitating life, or vice versa. But the illustrations in the book clearly

show a simple, workable design for a unicycle; a wheel, pedals, a seat, and

handlebars. If unicycles did not exist

before this book was published, it could certainly have inspired someone to

build one.

Part I, the Brolock! (Prologue), is a

short poem about a man named, Schnizerl; he builds a unicycle – and dies a

horrible death:

So

vas it mit der Schnitzerlein

On his

philosopede.

His

feet both shlipped outsidevard shoost,

Vhen at his extra shpeed.

He

felled upon der vheel of coorse?

De vheel like blitzen flew!

Und

Schnitzerl he vos schnitz in vact,

For it shlished him grod in two.

Part II is an

epic poem about Hans Breitmann and the unicycle he builds after Schnitzerl's gruesome death. Schnitzerl shows him how; his ghost draws him a picture with his disembodied hand:

Breitmann builds the unicycle,

rides it around town, falls down, gets up, demonstrates its potential for high speed,

runs into a tree branch and rolls down a hill.

Surprisingly, he did not break any bones:

He rollet de rocky road entlong,

He pounce o’er shtock und shtone;

You’d dink he’d knocked his outsides

in,

Yet nefer preak a pone.

A group of doctors pump him full

of schnapps and suggest all manner of ridiculous cures. When Breitmann recovers,

they all take the credit.

In the end, Breitmann discusses

the potential military application of the unicycle with “Dana of the Sun” (Charles Anderson

Dana, owner of the New York Sun

newspaper).

The punchline of the book comes

in the final lines and its final illustration:

Dey dalk in Deutsch togeder,

Und volk say de ent vill pe

Philosopedal changes

In de Union cavallrie.

Gott help de howlin safage!

Gott help de Indi-an!

Shouldt Breitmann choin his forces

|

| General Sheridan on a Unicycle. |

The poem was topical; General

Sheridan had been fighting Indians in the West since 1866. During the winter of 1868-69, he was in the

middle of prosecuting a campaign against the Cheyenne, Kiowa and Comanche

tribes.

|

| General Sheridan in Uniform. |

I seem to remember a balloon ascension in

F-Troop; but no unicycles. The

Buffalo Soldiers’ bicycle trek from Missoula, Montana to St. Louis was

real, but much later (1897).

Conclusion

The invention of the unicycle

grew out of the velocipede craze of 1868-1870. Unicycles may have been invented independently of high-wheeled "ordinary" or "penny-farthing" bicycles; the earliest images, descriptions and patents for one-wheeled velocipedes predate Eugene Meyer's wire-spoke patent by at least six months. Although it is possible that the first unicycle may have resulted from someone removing a rear wheel from an early high-wheeled bicycle, it seems equally likely that it was invented independently, perhaps by an unnamed Englishman (if Scientific American is to be believed), in an effort to improve the efficiency of the velocipede in accordance with well-known physical considerations.

-------------------

UPDATE: May 24, 2015.

UPDATE: May 24, 2015.

The term, "monocycle" appears in a French patent issued to M. Hamond in 1832. The brief notice of issuance describes the monocycle as a vehicle (voiture) with one wheel. See J.B.

Duvergier, Collection complète des lois, décrets d'intérét général,

traités interanationaux, arrêtés, circulaires, instructions, etc. , Année

1832, Paris, Société du Recueil Sirey, 1833, page 382. Although the notice does not clarify whether it related to a horse-drawn vehicle or self-propelled vehicle, it seems likely that it was a horse-drawn vehicle.

The French website, ParisVelocipeda, mentions Hamond's "monocycle" in an article about the history of tricycles. Although the word "tricycle," for a three-wheeled velocipede, dates to 1868, "tricycle" was used to describe three-wheeled, horse-drawn vehicles. "Monocycle" is mentioned as another velocipede-related word that had been used much earlier for a different technology.

The French website, ParisVelocipeda, mentions Hamond's "monocycle" in an article about the history of tricycles. Although the word "tricycle," for a three-wheeled velocipede, dates to 1868, "tricycle" was used to describe three-wheeled, horse-drawn vehicles. "Monocycle" is mentioned as another velocipede-related word that had been used much earlier for a different technology.

[i]

Christian Eckert, Geschichte und

Erfindung des Einrades (History and Invention of the Unicycle)http://christianeckert.eu/index.php/geschichte-und-erfindung-des-einrades.html

[iv] The first poem in the book, entitled Brolock!, appeared in the February 13, 1869 issue of Scientific American under the title, Hans Breitmann's Shtory About Schnitzerl's Philosopede, credited to the New York Sun. The same poem was also reprinted in numerous other newspapers, under the title, Schnitzerl's Philosopede, as early as February 12, 1869 (Perrysburg (Ohio) Journal. It is not clear whether Schnitzerl's Philosopede preceded Breitmann's Philosopede (in book form, with both poems), or came later; although a comment in an advertisement in the back of the book (a reference to the January issue of Haney's Journal) suggests that the book may have been published as early as January 1869.

[v]

Carsten Hoefer, A Short Illustrated History of the Bicycle,

page 3 (crazyguyonbike.com).

No comments:

Post a Comment