When the Chicago White Sox faced

the New York Giants in the 1917 World Series, the games reflected the patriotic

mood of the country in the wake of its entry into World War I:

The most impressive moment of the

afternoon was when, just before play was begun, the band began to play “The

Star-Spangled Banner.” The whole great

throng rose to its feet as a man and uncovered until the national air was

completed.

They were not white sox. They were red, white and blue sox.

Richmond Times Dispatch (Virginia), October 7, 1917, Sports Page 1

(Game 1 of the 1917 World Series).

The Chicago White Sox, featuring

legendary outfielder, Shoeless Joe Jackson, found themselves back in the World

Series for the first time in more than ten years. They won the American League pennant that

year with a franchise record 100 wins (against only 54 losses) – a record that still stands. They were an offensive and defensive

juggernaut; leading the league in both runs scored and ERA (2.16). They would beat the Giants in six games that

year. When they returned to the World

Series in 1919, after an off-year in 1918, they would lose to the Cincinnati

Reds – ON PURPOSE! No longer “red, white and blue sox”; they were the “Black Sox”.

But 1917 was a happier time in

Chicago, the home of “jazz.” Before game 2 of the 1917 World Series, the band “jazzed up” a national anthem and the crowd rose in unison, the men taking off their hats, with some of the ladies likely putting their hands over their hearts. It may have been the first major, public, national event at which all of today’s basic

national anthem rules of etiquette were widely followed; a pop-version of a patriotic song, and standing, removing hats and placing the hand over the heart for the playing of the Star-Spangled Banner.

“Jazz” music, and the word “jazz,” itself, were both new at the time; and had only recently become a household word outside of Chicago and the far-West. The practice of standing and

removing hats during the national anthem was also new enough at the time to garner specific attention in the press. The now-customary

practice of placing hands over the heart was barely

three months old. An unreliable pitcher,

the playboy grandson of a former President of the United States, and the wife

of a Brigadier General may each have played a role in the development of one or another of these now-familiar customs.

[UPDATE September 5, 2016: See my new post, A Stand-Up History and Origin of the National Anthem at Sporting Events, for examples of the anthem at the baseball games from as early as 1890.]

The Star-Spangled

Banner and the World Series

The World Series is nearly as old

as the custom of singing the Star-Spangled

Banner at the series. The World

Series has been played annually since 1903 (with the exception of 1904, when the owner of the New

York Giants took his ball and went home).

Although Major League Baseball’s official historian dates the first performance

of the Star-Spangled Banner at a

World Series game to September 5, 1918,[i]

evidence suggests that the custom dates back to at least 1913; and may extend

back even further:

Until this year it has been the

custom to start each game of the world’s series by playing “The Star-Spangled

Banner.” During this series, the Boston

rooters asked that they be allowed to open the seventh inning with the national

anthem. That might have been good form

in Boston, but Brooklyn citizens missed the usual opening.

The Washington Times (DC), October 12, 1916, page 10 (see video of the 1916 World

Series between the Red Sox and the Brooklyn Dodgers here).

The World Series was only about

twelve years old at the time. How long

does it take for something to become “custom”?

I imagine at least a few years – and perhaps all of the way to the

beginning in 1903.

We know it was performed at least in 1915; even

though President Woodrow Wilson and his fiancé, Mrs. Galt had no idea – they

were behaving badly:

[B]oth the President and Mrs. Galt

appeared to be so much interested in each other that they not only overlooked

some of the most stirring points of the game, but also the fact that the band

was playing “The Star Spangled Banner.”

The Sun (New York), October 10, 1915, page 1 (see a video game re-creation of

the 1915 World Series between the Phillies and the Red Sox here).

A band also played the anthem before a game

of the 1913 World Series between the Giants and the Phillies:

Stand Up for Anthem.

As the big band

finished its part of the entertainment it played “The Star-Spangled Banner,”

and before the few measures were rendered the great crowd rose as one man to

its feet, doffed its headgear, while even the players stopped their warming up

and stood with bared heads while the nation’s anthem was being played. In the same connection it was notable that in

the great array of pennants and bunting at the Polo grounds there was no

American flag in sight.

The Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), October 8, 1913, Daily Sport Extra,

page 10.

I could not find any specific

reference to the Star-Spangled Banner at any World Series earlier than 1913.

That we would still be singing

the Star Spangled Banner before baseball games one-hundred years later was not

a foregone conclusion; the Star Spangled Banner wasn’t even our national anthem

(at least not officially) at the time – nor would it be, until 1931.

In 1917, the band “jazzed up” one

of the “national airs.”

“Jazzing Up” the National Song

The unconventional singing of the

national anthem can generate controversy.

Jose Feliciano, for example, was famously (and unfairly) booed for his swingin’, Latin-tinged

acoustic performance before game 5 of the 1968 World Series. I guess some people unaccustomed to the style

of music felt that it did not have the appropriate dignity.

Over the years, I have rolled my

eyes at a succession of young pop-divas throwing musical curveballs. I am not as uptight about the lack of decorum

or dignity in their performances, as I am amused by their attempts to squeeze

more runs into one song than two teams typically score in an entire

series. A nice, clean, fastball –

straight over the plate – is usually a safer bet. But my personal favorite may be the least

conventional – Jimmy

Hendrix’ Star-Spangled Banner at

Woodstock in 1969.

Surprisingly, perhaps (given the

vehemence of the negative reaction to Jose Feliciano in 1968), the practice of

“jazzing up” the “national” song during the World Series is nearly as old as the

custom of singing the national anthem at the World Series itself. Before game 2 of the World Series, the band “jazzed”

up the “national hymn,” America – at

least they had the good taste to play the Star-Spangled

Banner straight:

The band found a sunny spot on the

field back of third base to-day and kept up a musical barrage fire for the

phalanx of song pluggers who annoyed the inoffensive atmosphere with noises

before the game. When the band began jazzing up “America” with many variations the

Chicagoans stood with heads bared.

The band was playing it for

one-stepping purposes, but the citizenry labored under the impression that it

emanated from patriotic motives. The

error is surprising in view of the fact that Chicago is

the home of the jazz. In New York

the boys would have intuitively grabbed themselves partners and started reeling

up and down the field.

Afterward the band in all sincerity

played “The Star Spangled Banner” and again the crowd stood at attention. This time the musicians thoughtfully left off the jazz notes.

Chicago Examiner, October 8, 1917, page 9, column 2.

Since the United States did not

have an official “National Anthem” in 1917,[ii]

“jazzing up” up America was nearly

the same as “jazzing up” the Star-Spangled

Banner. Although the Star-Spangled Banner had long been considered

the de-facto “national anthem” (it was referred to as such, at least

informally, as early as 1843[iii]),

it shared top-billing with, America,

in many people’s minds.

The United States Army and Navy,

however, gave top-billing to the Star-Spangled

Banner by as early as 1916; the general public was not quite up to speed

yet:

As I understand,

our Government and, above all, our people recognize two patriotic songs, “The

Star Spangled Banner” as an anthem and “America” first and foremost as our

national hymn. On the other hand, our

military and naval departments, much less our people, pay formal tribute to

“The Star Spangled Banner,” which is our national anthem.

University Missourian (Columbia, Missouri), April 20, 1916, page 3.

That there is a

lamentable ignorance, or else a worse indifference, regarding the conventions

and duties of citizenhood, is very evident when a large number of American

citizens take no notice of the playing of America’s national anthem, the Star

Spangled Banner, and do not even bother to remove their hats when the music

begins. . . . Maybe, some people do not

know what the national anthem is. Some

think it is “America,” but it is not, now-a-days.

The Maui News (Wailuku, Hawaii), May 4, 1917, page 4.

During the 1917 World Series, the

United States was in the midst of a wave of patriotism brought on by its entry

into World War I. People were just then

becoming accustomed to thinking of the Star-Spangled

Banner as the national anthem, and were learning the proper etiquette;

standing and removing one’s hat.

After game 1, a patriotic

journalist gushed:

The most impressive moment of the

afternoon was when, just before play was begun, the band began to play “The

Star-Spangled Banner.” The whole great

throng rose to its feet as a man and uncovered until the national air was

completed.

They were not white sox. They were red, white and blue sox.

Richmond Times Dispatch (Virginia), October 7, 1917, Sports Page 1.

Through the magic of YouTube, you can watch video

of game 1 here. The numerous flags

and (presumably) red-white-and-blue bunting draped throughout Comiskey Park

testify to the patriotic mood of the time.

You can see also see video of games 3 and 4 at

the Polo Grounds in New York.

Before game 3:

A few minutes before the Chicagos

took the field to practice Mayor Mitchel was escorted across the field by a

platoon of police to the mayor’s box in the grandstand. The band then played “The Star Spangled

Banner” while the thousands stood with bared heads.

Evening Star (Washington DC), October 10, 1917, Base Ball Extra.

In game 4:

While the White Sox were taking their

fielding workout the band played “The Star Spangled Banner,” while the

spectators stood with bared heads.

Before play began the Giants

assembled at second base, and each, with a flag of the allies of the United

States, marched toward the plate, while the band played “My Country, ‘Tis of

Thee.”

Evening Star (Washington DC), October 11, 1917, Base Ball Extra.

Chicago, Jazz, and the White Sox

It is not surprising that Chicago

was the site of the first “jazzed up” version of a “national” song before a

World Series game. Chicago was, after

all, the birthplace of the word, “jazz,” as applied to the new musical

genre. The word was borrowed from

“Western slang,” in which “jazz” meant pep or vim. Coincidentally, the Chicago White Sox were

present in California at the precise moment that the word, “jazz,” emerged from

the primordial slang-soup and crawled into the mainstream print-media.

The word, “jazz,” is attested

from as early as 1912; when it was first reported as the name of a pitcher’s

new, can’t-miss curveball. Before his

first start of the 1912 season, Ben Henderson, a pitcher for the Pacific

League’s Portland Beavers (a notorious drinker who had once been blacklisted for

violating the reserve

clause) hyped his new curve; the “jazz” (or “jass”) ball. Although the pitch did little to salvage his

career (see my earlier post, Ben Henderson’s Trouble With the Curve),

the word survived and eventually thrived.

The word disappears from the

written record at the moment Ben Henderson disappeared (he went AWOL on a

drunken binge, shortly after introducing his “jazz” ball); emerging again one

year later at spring training for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. This time, the word had more staying power.

In March, 1913, “Scoop” Gleeson

wrote of the Seals’ pre-season enthusiasm:

Everybody has come back to the old

town full of the old “jazz” and they promise to knock the fans off their feet

with their playing.

What is the “jazz”? Why, it’s a

little of that “old life,” the “gin-i-ker,” the “pep,” otherwise known as

enthusiasalum [sic]. A grain of “jazz” and you feel like going out and eating

your way through Twin Peaks.

San Francisco Bulletin, March 6, 1913 (see also, my earlier post, Is Jasbo Jazz, or Just Hokum and Gravy).

Years later, “Scoop” Gleeson

claimed to have learned the word from another sportswriter, “Spike” Slattery,

during spring training in 1913. Both

Gleeson and Slattery made regular use of the word “jazz” throughout the rest of

1913.

The Chicago White Sox were also

there. In fact, Art Hickman, an early,

successful “jazz” bandleader, picked them up at the station. Bert Kelly, an early jazz banjo player who

may be responsible for first applying the word “jazz” to a musical genre, may

have been there too (he is known to have been there during spring training in

1914).[iv]

The word “jazz,” in the sense of

vim or pep, was used in several Western states into at least 1916. Meanwhile, Bert Kelly left San Francisco and moved

to Chicago, where, in 1914 (or 1915) he claims to have been present at a wild

movie industry party (Chicago’s Essanay Studios were one of the leading studios

of the day) at the moment the word “jazz” was first applied to music.[v] Within two or three years, “jazz” music was

all the rage; and even the “national hymn” was fair game for reinterpretation.

Today, we take it for granted

that most people will stand and remove their hats during the Star-Spangled Banner. It seems to have been a notable occurrence in

the 1910s, however; accounts of the 1913 and 1917 make special mention of the removal

of hats and the baring of heads. In 1913,

the practice of removing one’s hat for the playing of the Star-Spangled Banner was still relatively new and not well established.

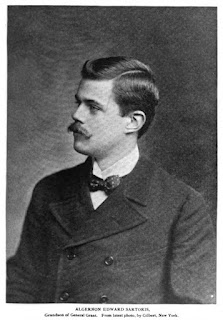

Removing Hats and Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant’s grandson, Algernon Edward Sartoris, was reportedly, “the first man in Washington to set the example of removing his hat when the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ was being played.”[vi] It is not clear, however, when he may have popularized the practice. At the time (1898), Algernon was just 21 years old. Although best known as an heir to an English country estate and “leader of cotillions, ornament of afternoon teas, club man and dilettante,”[vii] Algernon was an officer in the Army during the Spanish-American War; at same time that the practice of standing and removing one’s hat during the Star-Spangled Banner first received significant notice in the press. As a high-profile Washington socialite, he could well have helped popularize the practice there, before shipping out.

Ironically, Sartoris – Ulysses Grant’s

grandson – served under Captain Fitzhugh Lee, a former Confederate Cavalry

General and nephew of Grant’s Civil War nemesis, Robert E. Lee. Algernon Sartoris, however, was no career

soldier (are there any career soldiers named Algernon?). He signed up to impress his childhood

sweetheart and fiancé, Edith Davidge; whose failure to love him for the man he

was eventually drove him away. But

first, it drove him into the Army; and from there to Cuba – and later the

Philippines. She was unimpressed.

|

| The St. Paul Globe (Minnesota), April 24, 1904 |

After the war, she encouraged him

to seek honest work doing honest labor.

He appeased her by signing on at the bottom rung of the ladder at Westinghouse Electric Light Works in Pittsburgh; where he schlepped a lunch pail to work every

day in coveralls, and worked twelve-hour days, six days a week, for $1 a day; manly

yes – but perhaps not the ideal career choice for a former “ornament at

afternoon teas” who could still afford to be an ornament at afternoon teas. He soon left the drudgery of the factory, left

his fiancé behind, and boarded a ship for France to marry his other childhood

sweetheart, Mlle. Cecilia Noussiard, of Paris.

Although Algernon Sartoris may

have popularized the doffing hats during the Star-Spangled Banner in society circles in Washington DC, in all

likelihood, he did not originate the custom.

A plaque in Tacoma, Washington marks the spot where Rossel G. O’Brien, a

Civil War-era Brigadier General, is said to have first proposed the

stand-and-remove-your-hat rule at a meeting of the local chapter of a national

Civil War veterans’ group in 1893.[viii]

If true, O’Brien was apparently an early proponent of the rule, and may even be

responsible for introducing the rule to Tacoma.

It is unlikely, however, that the rule originated with him; or that his

proposal ignited a national trend.

[(Coincidentally, the man who coined the word "Dude" was a also a fixture in Tacoma high-society in 1893. Perhaps he and the General crossed paths. See my earlier post on the History and Etymology of "Dude.")]

In 1898, at the height of the Spanish-American

War, and in the middle of an intra-service squabble between reservists and

regular Army officers at Army posts in Kansas, a high-ranking, career military

officer said that rule originated at United States Military Academy at West

Point. He also said that our sacred,

patriotic custom of standing and removing one’s hat during the playing of the

national anthem was first introduced by – wait for it – foreigners:

No little

amusement has been excited among army officers at the articles which recently

have appeared commenting on the fact that volunteer soldiers stationed at

different posts in this vicinity have been seen to remove their hats when the

national airs have been played by the military bands, and adding that no

regular army officer was ever seen to do this.

An army officer

yesterday, of high rank, speaking on this subject, said: “The custom of

removing the hat when the national airs are being played has been in vogue for

many years among the men of the regular army.

I can remember the time when the practice was not observed

generally. It first started in the West

Point Military academy, and was introduced there through example of various

officers of foreign armies who visited the place.

“It was noticed

that whenever any of our national airs were played the foreigners invariably

would remove their hats and stand until the music ceased. This patriotic example was contagious, and it

was not long before the beginning of a national anthem by the post band was the

signal for every cadet in the hall to rise and stand uncovered. Since then the practice has spread until

today it is an uncommon thing to see a regular army officer who does not

observe it.”

The Topeka State Journal (Kansas), July 4, 1898, page 4.

It's not clear from his comments how long the custom of standing and removing hats had been followed at West Point, but we know that they stood for the "Star Spangled Banner" at West Point as early as 1889. At an unveiling ceremony for portraits of Generals Grant, Sherman and Sheridan at West Point:

The address was followed by "The Star Spangled Banner," played by the band, the audience standing.

The Chicago Tribune, October 4, 1889, page 2.

The unveiling ceremony was attended by an international Pan-American delegation who were in the middle of an American tour. Two months later, the same delegation witnessed a very different kind of protocol at the close of a joint session of Congress in Washington DC, attended by the President, Vice President, the Supreme Court and all members of the House and Senate. They played the "Star Spangled Banner" at the end of the session, and instead of having everyone stand still, they left the room during the song:

The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), December 12, 1889, page 6.

The unveiling ceremony was attended by an international Pan-American delegation who were in the middle of an American tour. Two months later, the same delegation witnessed a very different kind of protocol at the close of a joint session of Congress in Washington DC, attended by the President, Vice President, the Supreme Court and all members of the House and Senate. They played the "Star Spangled Banner" at the end of the session, and instead of having everyone stand still, they left the room during the song:

Washington's Grand March was rendered by the marine band. The martial strains having ceased, the vice president declared the joint assembly dissolved, and to the stirring air of the "Star-Spangled Banner" the invited guests slowly left the chamber.

But ten years later, with the rules of ettiquette more firmly established, and as the Spanish-American War

rolled on, the practice was picked up by other foreigners; in places

liberated from Spanish rule – or at least that’s how news reports seemed to paint it:

“HATS

OFF” IN PORTO RICO

That

is the Fashion When the Band Plays

“Star-Spangled

Banner.”

Special Cable Despatch to The Sun.

Ponce, Porto

Rico, Aug. 4. – The Reception of the American Army in Porto Rico continues in

an “Oh, be joyful” way. From Guayama, a

town where the Spanish were said to be gathering and intrenching, the people

sent word to Ponce that all the Spaniards had gone and the populace were

waiting to receive the Americans. One

company of troops was sent there and had a big reception. The American flag had already been hoisted

and everybody gathered around it. When

the soldiers came the people sang the “Star-Spangled Banner” in a mixture of

Spanish and English.

At Ponce every

time the band plays the “Star-Spangled Banner” the police run about and make

everybody remove his hat.

The Sun (New York), August 4, 1898, page 3.

An American officer stationed in

the Philippines wrote:

The natives are

very musical and every evening there is lots of music in the air. The other day I stepped in to listen to a

very good string quartet. You should

have seen them open their eyes when I played a “Hot

time” for them; they seem to think that this is our national air. Yesterday Aguinaldo’s band came

in and serenaded us. They played “Dixie”

“Yankee Doodle” and many other such pieces, ending with the “Star Spangled

Banner,” removing their hats first.

Barbour County Index (Medicine Lodge, Kansas), February 22, 1899,

page 1.

But not everyone was so

respectful; or at least not for long:

No better

illustration of the changed condition of affairs [(in the Philippines)] can be

cited than the conduct of the natives who frequent the American army band

concerts on the Luneta of evenings.

These concerts invariably conclude with the “Star Spangled Banner,”

during the rendition of which every American present removes his hat and stands

at “attention.” Formerly this custom was

imitated by the natives, but now the Filipino who pays any more respect to the American

national anthem than to “A

Hot Time in the Old Town” is a striking exception.

Guthrie Daily Leader (Guthrie, Oklahoma), March 11, 1899, page 1.

Back in the United States, a report of the Army-Navy football game in 1899 reveals that standing and removing hats was already mandatory at the United States military and naval academies. The sight of cadets standing for the national anthem appears to have been a novel sight at the time; civilians at the game liked what they saw and followed suit:

The Indianapolis Journal, December 11, 1899, page 4.

An admiral quoted in the same article said, "For nearly forty years I have saluted the flag of the United States uncovered and in the attitude of reverence;" suggesting that the custom of removing hats for the flag, and perhaps one or both of the national "airs," was already deeply rooted in military tradition.

Among civilians, the custom slowly gained wider acceptance in the years after the Spanish-American War. In some places you had to remove your hat quickly – or suffer the consequences:

An Inspiring Incident.

While the Annapolis players in the football game between the military and naval cadets were tumbling about the filed on the occasion of the recent game awaiting the appearance of their rivals, the band which came with them began to play the "Star-spangled Banner." At once every cadet within sound of the music, sailor or soldier, stood at "attention" and uncovered, as is the rule at those schools. Every other military or naval officer present obeyed the instincts of his training. There-at the audience of nearly 25,000 persons stood in silence and in an attitude of respect until the music ceased. It need not be said that it was an impressive scene and a lesson that will be long remembered.

While the Annapolis players in the football game between the military and naval cadets were tumbling about the filed on the occasion of the recent game awaiting the appearance of their rivals, the band which came with them began to play the "Star-spangled Banner." At once every cadet within sound of the music, sailor or soldier, stood at "attention" and uncovered, as is the rule at those schools. Every other military or naval officer present obeyed the instincts of his training. There-at the audience of nearly 25,000 persons stood in silence and in an attitude of respect until the music ceased. It need not be said that it was an impressive scene and a lesson that will be long remembered.

An admiral quoted in the same article said, "For nearly forty years I have saluted the flag of the United States uncovered and in the attitude of reverence;" suggesting that the custom of removing hats for the flag, and perhaps one or both of the national "airs," was already deeply rooted in military tradition.

Among civilians, the custom slowly gained wider acceptance in the years after the Spanish-American War. In some places you had to remove your hat quickly – or suffer the consequences:

The Christmas

decorations of bay leaves, pine needles and red ribbons and bells were still in

place. On a platform over the telephone

booths sat the Seventh Regiment band, and when the gong rang at noon it struck

up “The Star Spangled Banner.” Men who

didn’t remove their hats on hearing the first bar had them removed for them and

shot into the circumambient air, whence they returned to be once more violently

agitated and finally to disappear into the fourth dimension or the gallery.

The Sun (New York), January 1, 1905, page 13.

By 1909, some zealots even wanted

to pass a law making it mandatory – thereby making a mockery of the “land of

the free”:

One acrimonious

patriot wants a law passed compeling people to remove their hats when “The Star

Spangled Banner” is played. Desirable as

it is to thus show honor to the flag, a law compelling it would be a denial of

the sentiment of the famous hymn.

Tombstone Epitaph (Tombstone, Arizona), August 22, 1909, page 2.

And again in 1913:

Some one has

proposed that a law be passed compelling American citizens to salute their

flag. That is an excellent way to get

the flag torn up. Compulsory patriotism

like hired friendship is a mighty treacherous sentiment.

Tulsa Daily World (Oklahoma), February 19, 1913, page 4.

Although the custom of standing

and removing hats for the playing of the Star-Spangled

Banner gained ground throughout the early 1900s, it was not universally

observed. Even as late as 1913, standing

for the anthem in a theater might get you in trouble:

Because he

displayed his patriotism by standing in a local theater during the playing of

“The Star Spangled Banner,” J. Frank Wahl, formerly a sergeant of Company L, 2d

Infantry, National Guard of the District of Columbia, according to his own

story, was ejected from the theater.

The alleged

ejection of Mr. Wahl occurred Sunday afternoon near the close of the

performance. Several musicians on the

stage were performing for the last act played several patriotic selections, the

medley ending with “The Star Spangled Banner.”

. . .

It was while Mr.

Wahl was standing that the special policeman of the theater, he stated, came

down and caught hold of his collar and pulled him into the aisle.

“What’s the

matter?” Wahl said he asked the special policeman. He declares the man replied that he would

have to get out of the theater, and further that he was going to put him out.

Evening Star (Washington DC), October 21, 1913, page 2.

Progress was slow. In 1916, the director of a Marine Corps band

explained why he included special instructions in the program notes for people

to stand and remove hats during the national anthem:

I simply placed

this notice on the program to call the attention of some folks to the need for

paying proper deference to the national anthem.

Many of those

who attend the concerts of the Marine band do this, but others get up and walk

away, many sit still, and some men seem ashamed to remove their hats until some

one does it, then the rest follow.

The Daily Telegram (Clarksburg, West Virginia), July 21, 1916, page

6.

Men removed their hats; but what did

women do – other than standing?

Apparently nothing. But that all changed in the summer of 1917.

Hands Over the Heart

The rule, to stand and remove one’s

hat during the Star-Spangled Banner,

grew out of a military custom of standing and removing their hats. But, as most military veterans today would

recognize, that is no longer the custom.

The original custom, now practiced by civilians, changed sometime

between 1898 and 1914:

Not so very long

ago it was the proper slant on things patriotic for a soldier to stand at

attention, remove his hat, place it over his left shoulder and wonder what he

was going to have for “chow,” as the band played the national air and the

colors were brought in out of the weather for the night. Now enlisted men and officer alike remain

covered while the band plays “O say can you see,” only saluting with the right

hand to the hat brim when the last note of the famous Francis Scott Key battle

song reaches them across the alkali parade ground.

El Paso Herald (Texas), May 15, 1914, page 3.

Civilians were encouraged to

follow the older, hat-in-hand tradition; including the practice of placing the

hat on the left shoulder:

Civilians, are

expected to stand at attention with hats removed when the colors are passing or

being passed and when the national air (the “Star Spangled Banner”) is being

played.

El Paso Herald (Texas), May 15, 1914, page 3.

Men should

remove their hats, and keep them over the left shoulder until the flag has

passed.

The Commoner (Lincoln, Nebraska), July 1, 1917, page 10.

When performed using the right

hand, placing the hat on the left shoulder puts the right hand just about where

the “heart” is generally believed to be – at least for the purposes of “putting

your hand on your heart.”

Women, however, were not asked to

remove their hats. Hat-fashion of the

day may have made the suggestion impractical; large, complicated hats and small,

precarious hats were frequently attached

to the hair by an array of pins, combs, and other accoutrement.

There was also no precedent. All of the rules emerged from the military,

which was then an exclusively male institution.

What to do? – what to do?

In 1917, Katherine H. Harvey, president

of the Woman’s Relief Association, National Guard of the Disctirct of Columbia,

and wife of Brigadier General William E. Harvey, commander of the District National

Guard, decided what should be done:

The inspiring

sight of women standing “at attention,” with the right hand over the heart, may

soon be seen in the theaters and open-air places of Washington, where the

national anthem is played. And in this

Washington is expected to set a patriotic example for the nation.

Mrs. Katherine

H. Harvey . . . suggested today that Washington women do something more than

merely stand when “The Star-Spangled Banner” is played.

If the men of

the military service are required to salute, she says, the women of the nation,

too, should have a salute, of their own, denoting devotion to the flag. . .

.

[She said,] “Of

course, we always show our respect for the anthem by standing, but there is

always a tendency to put on one’s gloves or hat or otherwise prepare to leave. Few, indeed, stand at attention!

“Let us, the

women of the Capital, make this a national custom.”

The Washington Times, July 27, 1917, page 4.

And they did.

It’s a good thing too. Men’s fashions changed, and hats are no

longer the norm – now I

have a place to put my hand. And, it

provided a nice alternative to the straight-armed “Bellamy

salute,” the creepy salute that accompanied the Pledge of Allegiance until

Nazi-Germany spoiled it for everyone else.

|

| Pledge of Allegiance - 1941 |

Conclusion

The tradition of playing the Star-Spangled Banner before (or during) a World Series game dates to at least 1913 World Series between the Giants and the Phillies. The tradition may even date back to the first World Series in 1903; as suggested by reports critical of playing of the Star-Spangled banner to open the seventh-inning of World Series games in Boston in 1916.

The 1917 World Series may have been the first major, public, national event at which all of today’s basic national anthem rules of etiquette were widely followed. Patriotic fervor had the men ready, primed and willing to follow the lead of Algernon Sartoris, Rossel G. O’Brien, and unnamed foreign military officers, by standing and removing their hats for the playing of the Star-Spangled Banner. Many of those men may have placed their hats over their left shoulder, as was customary – resulting in their right hand being placed over their heart (hat-wearing was nearly universal at the time, so there were likely very few men in attendance who would not have had a hat to take off). The women in attendance stood “at attention;” and many of them may have placed their hands over their hearts, as encouraged by Katherine Harvey just a few months earlier.

The 1917 World Series may have been the first major, public, national event at which all of today’s basic national anthem rules of etiquette were widely followed. Patriotic fervor had the men ready, primed and willing to follow the lead of Algernon Sartoris, Rossel G. O’Brien, and unnamed foreign military officers, by standing and removing their hats for the playing of the Star-Spangled Banner. Many of those men may have placed their hats over their left shoulder, as was customary – resulting in their right hand being placed over their heart (hat-wearing was nearly universal at the time, so there were likely very few men in attendance who would not have had a hat to take off). The women in attendance stood “at attention;” and many of them may have placed their hands over their hearts, as encouraged by Katherine Harvey just a few months earlier.

The people of 1917 were also open

to avant-garde or pop-arrangements of

revered, patriotic tunes; without making too much of a fuss over it.

Play Ball!

[i] See, Doug Miller, “Key Connections:

Star-Spangled Banner, Baseball Forever Linked,” MLB.com, September 14, 2014.

[ii]

See, “Key Connections: Star-Spangled Banner, Baseball Forever Linked,” MLB.com, September 14, 2014.

[iii] The Madisonian (Washington DC), January

24, 1843, page 2 (“I wish to see an expression of the American Press with

regard to the propriety and good taste of naming one of our ships of war after

the lamented patriot and poet – the author of our national anthem – the Star Spangled Banner.”).

[iv]

See my earlier post, Is Jasbo Jazz, or Just Hokum and Gravy.

[v]

See, Is Jasbo Jazz, or Just Hokum and Gravy. Kelly gave two accounts; one, from 1919,

reported that the first use had been in 1915; a second, from a letter he wrote

to clear up the origin of the word, “jazz,” reported that the first use was in

1914.

[vi]

“A Washington Widow; Mrs. Nellie Grant Sartoris, Bride-elect of General

Douglass,” The Salt Lake Herald, June

26, 1898, page 20.

[vii]

“The Tangled Romances of General Grant’s Grandson Unraveled at Last,” The Saint Paul Globe, April 24, 1904,

page 31.

[viii]

See “Tacoma

Man the Reason We Stand for Star Spangled Banner,” Paula Wissel, KPLU.org, July

4, 2013.

Edited on 9/28/2017 to add references to the "Star Spangled Banner" played before the Pan-American delegation in 1889.

Edited on 9/28/2017 to add references to the "Star Spangled Banner" played before the Pan-American delegation in 1889.

No comments:

Post a Comment