When Charo

famously cooed, “coochie, coochie,” in her many guest-spots on The Love Boat in the late-1970s, she was

only the latest in a long line of entertainers who shook their hips in a

“coochie-coochie.” At the time, the

expressions, “coochie-coochie” (1894) and “hoochie-coochie” (1895), meaning a belly

dance-like erotic dance, was about eighty years old.

The Random House Unabridged Dictionary defines “hootchy-kootchy,”

“hoochie-coochie” or “cooch dance” as:

A sinuous, quasi-Oriental dance

performed by a woman and characterized chiefly by suggestive gyrating and

shaking of the body.

The danse du ventre (French for “stomache

dance”) or “mussel dance” (from “Musselman”, an archaic term for Muslim person)

became internationally famous during the Exposition

Universelle (World’s Fair) in Paris in 1889; whose other lasting gift to

the world is the Eifel Tower. The dance

became a fixture in American pop-culture during and after the World’s Columbian

Exposition – the Chicago World’s Fair – in 1893; which also introduced the Ferris

Wheel, the X-Ray and the Midway Plaisance.

A dancer

named “Little Egypt” frequently gets credit for popularizing the dance at the

fair, although she would have been only one of many dancers who danced various

forms of ethnic dances at several ethnic villages on the Midway Plaisance (if she were

even there).

But whoever danced the dance there - there is no evidence that they called it the "coochie-coochie" during the fair. During the fair, sources generally referred to the dance as danse du ventre, "mussel dance" (or muscle dance), "midway dance," or any of a number of geographic or ethnic designations, such as Egyptian, Algerian, or Oriental. It was only later that the exotic, erotic form of dancing popularized at the Chicago World's Fair became known as “coochie-coochie,” and finally “hoochie-coochie.” The earliest examples of “coochie-coochie” in print are from about one year after the fair closed; the earliest examples of “hoochie-coochie” appeared about one year thereafter. So where did "coochie-coochie" come from?

But whoever danced the dance there - there is no evidence that they called it the "coochie-coochie" during the fair. During the fair, sources generally referred to the dance as danse du ventre, "mussel dance" (or muscle dance), "midway dance," or any of a number of geographic or ethnic designations, such as Egyptian, Algerian, or Oriental. It was only later that the exotic, erotic form of dancing popularized at the Chicago World's Fair became known as “coochie-coochie,” and finally “hoochie-coochie.” The earliest examples of “coochie-coochie” in print are from about one year after the fair closed; the earliest examples of “hoochie-coochie” appeared about one year thereafter. So where did "coochie-coochie" come from?

From about

one year before the fair until about two years after the fair, such dances were

frequently called the “kouta-kouta.” The

dancer who introduced the “kouta-kouta” in 1892, claims to have learned the

dance in India, where she had worked for an “opera” company that operated

mostly in India and the Far East. She

danced the “kouta-kouta” in places as far flung as New York City, Indianapolis,

Washington DC and Chicago before bringing the dance to London in early

1894. During and after the fair, the

name “kouta-kouta” was also used more generally in reference to other dancers,

many of whom had performed at the fair. One reference, from 1896, even used the apparently transitional

name, “kutcha-kutcha.”

The

transition from “kouta-kouta” to “coochie-coochie” and “hoochie-coochie” may

have been influenced by a general familiarity with familiar song lyrics like,

“kutchy, kutchy,” used in at least two songs during the 1880s, and “ “hoochie,

coochie, coochie,” from “The Ham-Fat Man,” a staple of minstrel shows during

the 1860s, and origin of the word “ham,” as applied to bad actors.

“Hoochie-coochie”

may have been influenced further by a linguistic template favoring rhyming

reduplication expressions that begin with “H”, like “helter skelter,” hocus

pocus,” and “hodge podge”[i];

and earlier such dancing girl-related expressions like, “hurdy gurdy,” “honky

tonk” and “hula-hula,” all of which were in use before “hoochie coochie.”

Tracing the

separate histories and origins of the dance, the names of the dance, and

various dancers who helped make the dance famous, touches on several disparate

threads of pop-culture, celebrities of the day, and famous personages whose

names and personalities are still well known.

President

Theodore Roosevelt, P. T. Barnum’s grandchildren, and “Little Egypt” were all

involved in one early, notorious incident in which the “coochie-coochie” (by

that name) was at issue.

NOTE: This is Part

I of II, covering: The Seely Dinner; the Kouta-Kouta; Before the Fair; and The Fair.

The Seely Dinner

Between Christmas of 1896 and New Year’s Day of 1897, President

Theodore Roosevelt (President of the New York City Police Commission, still two

years from climbing San Juan Hill and four years from ascending to the

Presidency of the United States) took time out of his busy holiday schedule to

respond to a crisis in the Police Department. Captain Chapman had been accused

of official misconduct, and the high social

position of the accusers added fuel to the fire.

Famed restaurateur and hotelier Louis Sherry, Clinton

Barnum Seeley and Herbert Barnum Seeley (P. T. Barnum’s grandchildren) and

several prominent talent agents were among the accusers and witnesses. Theodore Roosevelt, himself, was rumored to

have been present during the incident; a claim he denied (he said he wasn’t

even invited[ii])

and no proof of it ever surfaced; but I am not above fanning the tabloid flames

more than a century later.

Roosevelt acted swiftly, setting a “trial” date (a police department

hearing, as opposed to a criminal trial) for January 7, 1897, although the

hearing would be postponed until January 14.

Despite the high-placed accusers and serious accusations, Captain

Chapman promised a vigorous defense:

Capt.

Chapman said yesterday that he would prove that the woman

danced with nothing on but stockings which reached to a point about two

inches above her knees.

The Sun (New York), January

1, 1897).

Captain Chapman stood accused of raiding Clinton Barnum Seeley’s

bachelor party without cause. The

accusers’ allegations were straight-forward:

Mr.

Seeley declares that the dancer known as “Little Egypt”

did not dance in a nude condition.

Ibid.

But “Little Egypt” admitted that the dance was “indecent” – but that

she did not dance alone:

Howard

B. Seeley, she says, danced the couchee-couchee

with her, and that revelry ran beyond the decency point. She also says that another woman also danced

in indecent dress. – New York

Advertiser, Dec. 31.

Alexandria Gazette (Virginia), January 2, 1897, page 1.

|

| The Washington Times (Washington DC), April 11, 1920. |

Facts brought out a trial suggested that the raid was instigated by

talent agents whose own dancers were snubbed in planning the dinner; and that

the police jumped at the chance to raid the party, in part, because of friction

with Teddy Roosevelt who was in the process of trying to clean up the

department.

At the time, the expression, “coochie-coochie,” as the name of a

dance, was only a couple years old.

Before then, the dance was generally referred to as the “mussel dance”

(sometimes “muscle dances”, from “Musselman”, an archaic term for Muslim

person), the danse de ventre (French

for “belly dance”), or “kouta-kouta,” the expression that gave way to “coochie-

coochie.”

|

The Dream City: A Portfolio of

Photographic Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition, St. Louis, N. D.

Thompson Publishing Co., 1893 (pages unnumbered).

|

The Kouta Kouta

In May of 1892, a “character actress” and “skirt dancer” named Avita

(sometimes Vita, or Ada Vita), the “Vital Spark,” introduced the “Kouta-Kouta”

(sometimes Koota-Koota) in a production of “Elysium”:

A

novelty in dancing, it is announced, will be seen in “Elysium” at Herrmann’s

Theatre next week. It is called the “Koota-Koota,” whatever that may mean, and is danced by

Avita, an English character actress, who is said to have performed it before

the Rajah during her visit to the East Indies. Isn’t that real nice?

The Evening World (New

York), May 13, 1892, page 5.

Avita had been performing in New York City and Boston since at least

November 1891, sometimes billed as a “skirt dancer”; the kind of dancer who

might kick up her skirt in a “can-can” or while singing “Ta-Ra-Ra

Boom-de-ay!” Her appearance in “Elysium”

is the first time her dance is called the “kouta-kouta.”

Two years later, when she was in London, she described her background

and how she came to learn the “kouta-kouta”; she also says that she danced the

dance at the Chicago World’s Fair:

The “Kouta-Kouta”

Dancer.

“Vita’s” dance at the Trocadero

is on the honi soit

order. It is apparently suggested by

the danse du ventre that came

westwards with the last Paris Exhibition, but it does not go the lengths that

it did there. Still it is novel and

daring, and will cause a lot of talk. In

the course of a few minutes’ chat that I had with “Vita” the other day she told

me that she was born in San Francisco twenty-two years ago, and inherited her

love of the stage from her mother, who was a famous dancer in Italy. She was educated in Paris at the Convent of

the Sacred Heart, and afterwards went back to San Francisco.

“How did you come to go on the

stage?”

“Oh, I was always fond of the

stage, and never happier than when appearing in amateur theatricals.”

“And this dance?”

“I learnt it in India when I was with the Stanley Opera

Company.[iii] The favourite dancing girl of one of the

Rajahs taught me all about it, and when I danced it in

the Chicago Exhibition you cannot imagine what a furore it caused. In England I am sure it will excite just as

great interest. Don’t you think so?”

Today (London), Volume 1,

January 20, 1894, page 21.

The Middle-Eastern dance was appropriate in the story of “Elysium”; an

adaptation of a French play which was based on Mario Uchard’s book, Mon Oncle Barbassou[iv]

(My Uncle Barbassou[v]). After reports of Uncle Barbassou’s death in

“the East” surface, his nephew goes out to take possession of his inheritance,

which includes a harem of eight beautiful women (four in the novel). The nephew falls in love with the most virtuous

harem girl; Uncle Barbassou shows up alive (he had just been trying to evade

his first wife). Although the virtuous

love-interest refused to dance, other “gems of the Orient,” as the harem girls

were called, were dancers – and one of them danced the “Koota-Koota”:

The

scene in the harem, which is called Elysium, is enlivened with the “Koota-Koota” dance by Avita, a “Rose” dance by

Gertrude Reynolds, and songs in café chantant style by Mlle. Ottilie.

The Times Picayune (New

Orleans, Louisiana), June 19, 1892, page 16.

Intriguingly, but perhaps merely coincidentally, one of the harem

girls was named “Koochi.” Avita played a

character named “Zoura” and Jenny Goldthwaite played “Koochi,”[vi] and when “coochie-coochie” became a common

expression two or three years later, it was no longer in the context of the

play; so any connection to the character named “Koochie” seems unlikely.

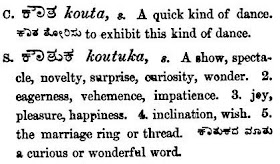

If Avita’s claims to have learned the dance in India is to be

believed, and the name of the dance did come from India, there is a

plausible linguistic connection to the Kannada or Canarese language, spoken by the Kannada people of Southern India:

Of course, it would be more interesting if the meaning were more in the nature of the word, “koota” or “kuta,” which can have a more salacious meaning:

Professor S. N. Sridhar, Professor of India Studies at Stony

Brook University, confirmed that “koota” still has one of at least three different

meanings; a social club, where

members gather together (the Association of Kannada Kootas of America (AKKA) lists 37 member “Kootas” throughout North America); a form of

horoscope used in planning

marriage compatibility; or sexual intercourse. A Kannada/English Dictionary published in

1894 also lists the word, “kuta,” as being “an imitative sound . . . the noise

of boiling water.”[vii] It is possible, I suppose, that any one or

several of the alternate meanings may be behind the name of the dance Avita brought to New York City in 1892.

|

| William Reeve, A Dictionary, Canarese and English, Bangalore, Wesleyan Mission Press, 1858. |

|

| William Reeve, A Dictionary, Canarese and English, Bangalore, Wesleyan Mission Press, 1858. |

Avita stayed with Elysium for about two months, and then went out on

tour with Reilly & Wood’s show, “Hades and the 400”; a satire on New York’s

elite – the “400” – with costumes seemingly inspired by Heironymous Bosch:

|

| The Indianapolis Journal, September 11, 1892, page 16. |

Between September 1892 and December 1893, she brought the

“kouta-kouta” to Indianapolis, New York City, Washington DC, and presumably

points in between, including Chicago; before going to London in early

1894.

Avita was doing more than the “kouta-kouta” with Reilly & Wood;

she also played nanny to one of the owners’ children. Charles Borani, one of “the Disappearing

Demons, Bros. Borani” who appeared on the bill with Vita was married, but his

wife was not around and his daughter traveled with the show. In a contested divorce proceeding, he claimed

that his wife was a drunk and took lovers; she accused him of having at least

two co-respondents, Avita and the famous Spanish dancer,

Carmencita; and Avita claimed to be just the nanny. He won the case and married Avita within the

year – but only after she got her own divorce:

|

| The Evening World (New York), December 20, 1893, page 1. |

When Avita left “Elysium,” she was replaced by another dancer with an

interesting past; Omene, the subject of raciest picture I have ever seen

published in a mainstream magazine published in the 1890s.

|

| Metropolitan Magazine (New York), volume 5, number 2, March, 1897, page 218. |

Omene’s career started as the”Circassian” assistant to a mock-Japanese

magician, Yank Hoe. They performed their

act in London before coming the United states in 1889. One of his tricks was to place a potato on

her throat, and cut it with a sword.

By June 1891, she was headliner in her own right, as an exotic

dancer:

“The

Tar and Tartar” company, at Palmer’s is treating New-Yorkers to the novel

sensation of a genuine Oriental dance. Omene, the Circassian

dancer, who began her engagement on Monday night, is a type of the

dancing girl of the East. Her dancing is

as different from that of the Spanish skirt variety as the latter is from the

Italian ballet variety. Omene is

remarkably graceful in her contortions and promises to be as popular in her way

as Carmencita.

The New York Times, June 24, 1891.

Her sexual style soon landed her in hot water:

“Too

Risque.”

Omene,

the new Turkish dancer, has been withdrawn from the “Tar and the Tartar.” Her

“Dance of the Harem,” although graceful and, from description, like the hula-hula of Hawaii, was considered too

“risqué.” There is no kick in the dance; it is a

swaying, continuous wriggle. The

original costume consisted of thirty-five yards of silk gauze and nothing

more. This was wrapped around the body

so as to form the semblance of a garment that partially enveloped the bust and

reached down to and encircled her knees.

The effect was as though she was dressed in short Turkish trousers. The legs from the knees down disdained any

impediment, while through the diaphanous material around about the dancer the

undulating, swaying outlines of her body were visible.

The Morning Call (San

Francisco), July 5, 1891, page 11.

But she put the notoriety to good use:

Omene,

the ex-Tar and Tartar dancer, is advertised now as a young woman whose dancing

and posturing had to be suppressed by the management.

Los Angeles Herald, July 18,

1891, page 1.

A magazine article from 1897 refers to Omene as the only beautiful one of

the famous danse du ventre artists;

the article also gives a different spin on the history of the dance in the

United States – older, and from a different source:

The

danse du ventre, which has raged more or less fiercely since the Columbian

Exposition in 1893, first came into public notice at the Paris Exposition of

1890. Until recently the dance had sunk

to the lower class of variety shows and stag dinners, but recent developments

of the Seeley dinner episode has had the effect of reviving it. Little Egypt has achieved the most notoriety

in this respect, and the dance is rather frowned upon now than otherwise. Fatima is another well-known exponent of the

wriggle, while Omene – really the only beautiful woman of the entire lot – has

done the dance at times.

The

negroes of the South have long performed this dance as a part of the Voudoo

ceremonial, and it was familiar to those who frequented houses of ill fame in

the South years before it came into public notice.

Metropolitan Magazine (New

York), volume 5, number 2, March, 1897, page 218.

The Metropolitan Museum published

a blog-post[viii]

that chronicles episodes from Omene’s colorful life; her invented Turkish

heritage (court records identified her as Madge Hargreaves), her stormy

relationship with her mock-Japanese magician husband “Yank Hoe” (court records

identified him as Ercole Castignone), her ill-fated affair with the Marquis

Edmundo de Olivieri, her widely reported visit to Chicago’s “Suicide Club” (the

only woman ever allowed inside), and death in Montreal in 1899.

Omene was also a shrewd businesswoman.

She followed the money out West to mining camps in Montana and

eventually to Alaska, during the Yukon Gold Rush. She also owned a half-interest in the Olympia

Theater in Seattle, where she sometimes shared the bill with Edison’s Wonderful

Projectoscope:

I imagine her as a sort of “Miss Kitty” of Gunsmoke fame – a

saloon-keeper/dancehall girl with a heart of gold (Google it, kids).

|

| Omene Cabinet Card (New York Public Library Digital Collection) |

Although Avita and Omene were two successful danse du ventre entertainers, they were not the first. And, although the dance became known in Paris

in 1889, it was danced in Paris at least as early as 1866.

Before The Fair

Our

Paris and Continental Correspondence.

Paris,

April 6, 1866.

The

next packet boat expected at Marseilles from Alexandria will bring over a dozen

or sixteen Egyptian dancers, who have been hired, or, more properly, bought, at the last fair at Fanta. This entirely new style of cargo is destined

for one of our great Paris theatres – that of the Port St. Martin.

The Evening Telegraph

(Philadelphia), April 24, 1866, page 2.

In the United States, non-dancing, exotic Middle Eastern beauties

became a staple of “museums” and side-shows as early as 1865, in the form of

the “Circassian

Beauty; first displayed by P. T. Barnum. [ix] Omene, herself, was sometimes billed as

a “Circassian Beauty” in advertisements for her partner “Yank Hoe’s” magic

shows.

Evening World (New York),

August 15, 1889.

“Nautch” dancing was a form of erotic dance that enjoyed some success long

before the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

Reports from travelers in India described the tradition:

The

nautch girls are a caste in India – pariahs, it

may be, but very beautiful. They never

marry and accumulate great wealth. . . .

It cannot be supposed that in the house of a respectable Hindoo merchant

in Delhi any improprieties would be allowed in a nautch, but it has been

surmised that in less respectable places the performance is carried into the

regions of indelicacy, and that, by the conclusion of the performance, the nautch girls retain but little of their costume except

the jewelry which adorns the person. . . .

Their pleasures may well be imagined to degenerate into orgies which are

fortunately unknown in Western lands.

The New York Herald, May 24,

1869, page 5.

|

| Dance of the Nautch Girls (1858) (New York Public Library Digital Collection). |

In 1870, Niblo’s

Garden in New York City presented the play, “The Black Crook,” which

included a “Nautch Girls Dance.”[x] As early as 1884, P. T. Barnum traveled with a troupe of

“Nautch girls, with pliant and voluptuous, though dusky, limbs”.[xi] Perhaps that is where his grandsons

acquired an appetite for erotic dance.

In 1888, Thomas Stevens reported seeing Nautch dancers performing at

what he called “Kootub Minar” (now generally spelled Qutub Minar / Qutub – Koota – hmmmm?) while on his round-the-world bicycle

trip:

An idea

seems to prevail in many Occidental minds that the Nautch dance is a very

naughty thing; but nothing is farther from the truth. Of course it can be made naughty, and no

doubt, often is; but then so can many another form of innocent amusement.

Thomas Stevens, “Around the World on a Bicycle. Through India XXVII”, Outing, volume 11, number 4, January

1888, page 362.

In 1884, the image of "Oriental" dancing girls was familiar enough to readers of the satirical magazine, Puck, that a cartoonist could depict the home of a Mormon polygamist as a Middle Eastern harem:

In 1886, General Custer’s widow saw the Italian-American dancer,

Bonfanti (whom she had seen in “The Black Crook” 26 years earlier), dance an

erotic Egyptian dance – the “Bee Dance,” which was apparently something like

the “dance of

the seven veils”:

She

sways and undulates over the stage with a gauze scarf in executing the bee

dance of the Almas . . .

New York Tribune, January 2,

1886, page 5.

Gustav Flaubert saw the “bee dance” in Egypt in 1849 and the dance was danced in the United States as early as 1867, although it

seemed to enjoy a brief renaissance in the late-1880s.

In 1892, one year before the Chicago World’s Fair, a new erotic

dance fad based on the “bee dance” swept the nation – it was the “Serpentine Dance”:

Numerous

young ladies and gentlemen are claiming the honor of inventing or first

introducing it. They forget that it is

only a development of Pharaoh’s favorite “bee dance,” still to be met with on

the banks of the Nile. . . . The exertion of working the 80 yards of China silk

into graceful folds is about equal to the muscular exercise involved in a

performance with the Indian clubs, and the foot dancing is necessarily

confined to a small space, for fear of entanglement.

Pittsburg Dispatch

(Pennsylvania), September 17, 1892, page 9.

The captivating movements of the dance intrigued early film pioneers. The Lumiere Brothers and Thomas Edison captured the movements of one of its most famous practitioners, Loie Fuller, on film. You

can see her today on YouTube.

But the poster may be more interesting than the film:

Like many other prominent dancers, Loie Fuller led a colorful

life. She “married” a man named William

B. Hayes by civil contract (he claimed to be a nephew to President Rutherford

B. Hayes); sued him for bigamy when she found out that he was already married;

and was sued by his real wife for $3,300 in an effort to recover money that he

had given to Loie to help her open a burlesque company in Cuba; all in a day’s

work for a hard-working Victorian dancer.

In 1888, P. T. Barnum’s circus traveled with a troupe of “Moorish”

dancers. Although the dance was not

described, it may well have been similar to the danse du ventre that came to prominence the following year in

Paris:

Barnum’s

at its Biggest. The children and a good

many of the grown folks discovered that the Bedouins look exactly as they do in

illustrated Bibles and Sunday school books, but when four girls with short

Moorish dresses danced on a high platform to voluptuous music, the resemblance

ceased.

The Sun (New York), April 3,

1888, page 2.

|

| Waco Evening News (Texas), October 9, 1888. |

The hit Broadway musical comedy, “A Brass Monkey,” of 1888 (the show

that helped popularize the expression, “Razzle-Dazzle”) included a “Dance of

the Orient,” reflecting at least a passing familiarity with, or interest in, Eastern dance styles.

And, when the “stomach dance” became a big hit in Paris the following year, the satirist Bill

Nye (not the science guy), reporting from Paris, immediately recognized its box-office

potential:

I paid

my money and visited the concert and stomach dance

of Algeria. The hurdy-gurdy

of the transmission country and the can-can of

the continent are not knee-high to this great exhibit. It is barbaric. It is heathenish. It is unique.

If a New York man with money will take the troupe over to America, he

will make more money than anybody. . . .

She is

attired in a cool costume of white mosquito netting and a Marseilles quilt,

which she lays aside when she begins.

She also wears gold anklets when the weather is cool, and a silk scarf

in each hand as she proceeds with the dance, allowing joy to be entirely

unconfined. . . . her corset bill is very small. . . . Several people from

America went away while she danced, but a Frenchman and I remained. I stayed because, as a newspaper reporter, I

have become accustomed to sights which would shock other people, and the

Frenchman, remained because he was a Frenchman.

The Indianapolis Journal,

July 14, 1889, part 2, page 12.

|

| Bill Nye “shocked” by the Danse du ventre in Paris. |

With the “nautch dance”, “bee dance,” “serpentine dance” and

“oriental” dancing, generally, finding success on the legitimate stage; and

with P. T. Barnum traveling around with exotic dancers; the public was primed

for a more brazen style of erotic dance; and they got it with Avita and

Omene. And then, the “Midway dance,” or

“kouta-kouta,” took the country by storm during the Chicago World’s Fair of

1893. And Bill Nye (not the science guy) enjoyed his second opportunity to see the dance:

As a brief aside, Bill Nye may have been a patron of the fine arts (or just an accidental genius). The composition of his Midway Plaisance sketch (a dancer in the background, with a headdress and arms in the air, framed above the neck and scroll of a double bass in the foreground) is similar in many respects to Degas's 1882 painting, "Blue Dancer," which was featured on the BBC's "Fake or Fortune" series.

|

| "Bill Nye at the Fair," The Sunny South (Atlanta, Georgia), September 30, 1893, page 3. |

|

| Fake or Fortune? Edgar Degas' Blue Dancers, BBC.com News, September 14, 2012. |

The Fair

To celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus

“discovering” the New World, the city of Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian

Exposition 1893. The centerpiece of the

fair was the “The Highway Through the Nations” located on the Midway Plaisance; an Epcot Center-style

row of exhibit spaces, each highlighting the culture of different countries and

regions from around the world.

The word “midway,” meaning the entertainment area of a fair or

carnival, is derived from the Midway

Plaisance of the Chicago World’s Fair.

The name Midway Plaisance,

itself, however, predates the fair:

Midway Plaisance was the name given by

the founders of the South Park system of Chicago . . . to a strip of wooded

land one mile in length . . . connecting the two great parks of the south

division of the city, Jackson [(the site of the World’s Columbian Exposition)]

on the east, and Washington on the west.

The word “plaisance as used in this connection signifies “pleasure way,”

and as such it was accepted and used by Chicago people up to the commencement

of preparatory work upon the World’s Fair.

John J. Flinn, The Authorized

Official Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893.

Some accounts of the Midway accuse the organizers of giving the Midway

a racist or Darwinian organization, with “primitive” cultures at one end giving

way progressively to more and more “civilized” or familiar cultures.[xii] The official map of the Midway, however shows

no such bias.

The South Seas Islanders Village and Javanese Village were both closer

to the fair entrance than the Austrian and German Villages. The Dahomey Village (Ghana) and the Chinese

village were both closer to the fair entrance than the Hungarian Concert Café

and the American Military Camp. Whatever

the order was, it does not appear to be “Darwinian,” or overtly racist; unless

Darwin liked South Seas Island music better than Hungarian music; which he may

have. And, the two Midway concessions

closest to the entrance to the fair were the Blarney Castle and the Diamond

Match Company on the other. I’m not sure

that the organizers believed that the gift of gab and instant fire were the

pinnacle of human achievement.

|

| John J. Flinn, Official Guide to the Midway Plaisance, 1893. |

Exotic

Dancers

Several of the villages provided dance exhibitions, some more shocking

than the others. “Ten pretty girls known

as the ‘Troupe of the Bella Bayah’” danced, at the Persian Theater. The Tunisian and Algerian Village featured

“haughty odalisques and sultanas brought from a Moorish Harem” as well as

“dancing girls” who performed in a hall with seating for 1,000. There were Irish pipers and jig dancers,

Hungarian dancers, Dahomeyan (Ghanaian) dancers, Brazilian dancers, Moroccan

dancers and Javanese dancers. But the

ones who caused the biggest stir were the dancers of the Egyptian Theater in

the “Streets of Cairo” exhibition.

The revised Official Guide to the Midway, issued in August of 1893,

about half-way through the fair’s run, featured an image of the “Egyptian”

dancers as the focal point of the cover illustration. When the fair opened, organizers imagined it

as a lofty educational and industrial enterprise. But after the first six weeks of the fair

proved to be a financial disaster, however, the powers that be brought in some

professional help – a “snake oil salesman” - literally.

The fair managers turned over the promotion of the fair to a

successful patent medicine salesman who brought in a number of amusement managers

and circus managers to save the fair:

They discussed the

business for three days and unanimously decided that the fair was but a big

show and that show rules applied to it and that the show features would have to

be brought out somewhat stronger if the thing was expected to pay. There was a midway there then, but it was

decided that it did not have enough drawing powers and that it should be

increased ten to twenty-fold; that for every hootchy-cootchy [(the story was

written seven years after the fair, using terminology that was apparently not

current during the fair)] or other dancer, elephant, wild bear or monkey that

was to be found on the streets of Cairo there should be at least ten more added

and everything else in proportion and that as far as possible everything should

be run ‘wide open.’ To use a show term.

It was decided that all the rest of the fair should be allowed to take

care of itself if it would, but forced if it would not, until a change came in

the condition of things, for it seemed to be sure that as the reformation from

a fair to a show took place the thing would pay.

The Evening Star (Washington

DC), May 5, 1900.

The new guidebook, written several weeks after the fair-management

shake-up, featured the most notorious of the fair’s dancers prominently on its

cover. Although it might seem odd that

the fair would publish a new official guidebook so close to the end of the fair

(It opened on May 1, 1893 and closed October 30, 1893), the new guidebook would

prove useful for more than a year after the fair closed. Although the fair, proper, closed as

scheduled in October, 1893, the Midway Plaisance, along with many of its

attractions stayed open until early 1895:

The Java village, the streets of Cairo,

old Vienna and the Dahomey [(Ghanaian)] people only came to their closing

exhibition in the Midway plaisance on Chicago’s lake front last week! It seems

incredible that they should still have delighted sightseers a full year after

the exposition closed. – Philadelpia

Ledger.

The Philipsburg Mail

(Philipsburg, Montana), January 10, 1895 (citing the Philadelphia Ledger).

One reviewer was unimpressed, devoted plenty of ink to describing, in

salacious detail, exactly what it was that he did not like about it:

Over in the Cairo theater may be found

the other extreme. The performance is

begun by a dusky beauty in a peacock blue skirt with gold fringe about the

bottom, and old gold ribbons hanging from the top. She wears a waist to match, but it has only

two points in front, just enough for a fastening. The skirt hangs upon the hips, and the

betting man offers three to one the dancer will lose it, but it looks like a

cinch, and he can get no takers. The skirt

and the waist are not on speaking terms, and the yawning breach is bridged by

an unmentionable nether garment, which permits a free lay of the abdominal

muscles. This garment also covers the

decolette charm in the bodice. There are

bracelets about the dancer’s ankles strings of beads hang from her neck, and a

flock of brass beer checks have made a nest in her hair. . . .

Fatima, the girl in blue, doesn’t prance

up and down the stage, or go into mad gyrations, or try to kick a hole in the

ceiling. She keeps time in timid little

steps, and occasionally sidles about the stage in slow, gliding circles. It seems to be her pet ambition to disjoint

herself at the hips, though a man in yesterday’s audience thought she was

suffering from an overdose of green apples.

At any rate, her anatomy below the waist and the knees performs a series

of violent tremors, spasms and contortions.

She literally humps herself in this wild agony, and occasionally turns

her back to the audience to give ocular proof.

Tiny cymbals fastened to the dancer’s fingers like castanets keep up a

clanging accompaniment. It is long after

the audience is weary of the monotonous performance before Fatima shows signs

of exhaustion. The cymbals stop to take

breath, the eye-lids drop, a languourous tremor sweeps thro’ the swaying body

and the dancer is about to drop asleep.

Unfortunately the tambo player wakes up at this inopportune time and

starts a new bar of music. That banishes

sleep, and the poor girl has to do it all over again.

Sensibilities are Shocked.

This is the dans du ventre. It might

fracture Anglo-Saxon susceptibilities even to name it in English. Many ladies seem to get their money’s worth

before it is half over, for they leave the theater. The dans

du ventre is quite a strain on American sensibilities, but many want to see

it as one of the oriental curiosities of The Fair. It is not likely to become popular in this

country, and yet it may be well in our virtuous dignity to remember that this

was said a few years ago of the can-can, which is now familiar as the skirt dance.

Several varieties of this dance are given

in the street in Cairo, but the distinctions are two subtle for American

perception. They appear to consist in

differently colored dresses. In one

example two girls do team work, which seems to be a scheme to take a mean

advantage of the ignorance of the audience and let a novice practice on

it. The oriental orchestra gets weary on

the slightest provocation. At the end of

each dance it sneaks out to see a man and take a nap, and a new band files in.

The Sunday Inter-Ocean (Chicago,

Illinois), June 4, 1893.

Another contemporary witness missed the more “naughty dances” that he

heard were to be seen at night, but briefly described the “muscle dance”:

You hear a great deal of talk about

naughty dances on the Midway. I passed

through this resort in the day time, and didn’t see any of the naughty dances –

if such there be. They do say, however,

that a night on Midway will reveal several things not seen in the day. I saw the muscle dance in the Turkish theatre. As an exhibition of control over the muscles

of the body the dance was a howling success, but as a thing of beauty it was

not in it. But that does not affect the

price of a ride on the camel.

Asheville Daily Citizen

(Asheville, North Carolina), October 13, 1993.

The Princeton Union

(Princeton, Minnesota), September 14, 1893, page 6.

Another eye-witness to the dance was also (at least officially)

unimpressed; he also criticized what he saw as hypocrisy in the widespread

moral outrage about the dance:

The “Midway” owes a good deal of its

attractiveness to the ferociously virtuous old ladies and epicene old gentlemen

who made its popularity by denouncing it.

It looks almost as if it were a “put up job” between the social purity

people and the fakirs, to boom the thing by “indexing” it. . . . The objects to which curiosity has been thus

directed are the dancing girls of various Oriental nations: Turkish, Algerian,

Egyptian. Modesty in dress or undress

really seems to be a matter of latitude – of climate – of custom. The Oriental woman would not bare her bosom

below the armpits, as American and English women – prudish enough in other

respects – do, nightly at balls of the best society. The Turkish dancing girl does not display

every line of her form in gauzy tights as do the ladies of the ballet, every

night upon the stage.

The Yellowstone Journal,

October 24, 1893 (Miles City, Montana).

|

| The Algerian Theater, Photographs of the Midway Plaisance (1904). |

We may forgive these writers for apparently conflating “Turkish” and

“Egyptian” dancers. In 1893, Egypt had

been part of the Turkish-controlled Ottoman Empire for centuries, and had only

recently been occupied by England, although it would technically remain part of

the Ottoman Empire until World War I. My

Norwegian great-grandfather fell victim to the same sort of mistake when he was

listed as Swedish, of all things, on his arrival documents. Norway was, at the

time, under Swedish control. I know that

when I was young, I probably loosely referred to all residents of the Soviet

Union as Russian, the Russian dominance obliterating the notion of “union.”

But some writers could and did distinguish from among some of the

various “exotic” dances on display in Chicago and other fairs afterwards.

|

| The Sunday Inter-Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), June 4, 1893. |

Nearly all of the references to the “kouta-kouta” dance at the

fair were published during the year following the fair’s end; with the earliest

accounts appearing within just a couple months of its October 31 closing date. During the fair, nearly all of the accounts

that I have seen refer to the dance variously as the danse du ventre, “mussel

(or muscle) dance” or “Egyptian/Turkish/Algerian/pick-your-exotic country

dance.”

I have seen only two references to the "Kouta Kouta," or the like, from during the run of the fair.

In August 1893, the Isabella Theater at 61st and Cottage Grove, in the "World's Fair District" of Chicago, featured a dancer billed as Princess Kuta Kuta doing the "Dans de Vauntre":

An advertisement for her return engagement at a recreation of the pleasures of the Midway two years later gives an idea of her charms and her "Pungent Dance":

And again during the fair, an advertisement for a new-fangled midway attraction was hyped as being "miles ahead of the Kota Dance”:

In August 1893, the Isabella Theater at 61st and Cottage Grove, in the "World's Fair District" of Chicago, featured a dancer billed as Princess Kuta Kuta doing the "Dans de Vauntre":

|

| Chicago Tribune, August 20, 1893, page 29. |

This Season's Grand Triumph.

Theater Turned Into an

Oriental Bower of Beauty . . .

Positive Engagement and First Appearance of

LA BELLE ROSA,

Star Dancer and Peerless Beauty of the Turkish Village at the World's Fair.

PRINCESS KUTA KUTA,

"Light of the Harem" and Unrivaled Oriental Dancer.

Theater Turned Into an

Oriental Bower of Beauty . . .

Positive Engagement and First Appearance of

LA BELLE ROSA,

Star Dancer and Peerless Beauty of the Turkish Village at the World's Fair.

PRINCESS KUTA KUTA,

"Light of the Harem" and Unrivaled Oriental Dancer.

And again during the fair, an advertisement for a new-fangled midway attraction was hyped as being "miles ahead of the Kota Dance”:

FOR SALE.

THE

STRONGEST GRAFT ON EARTH IS

NELSON’S X-RAY

For

looking through a person’s body. It’s

taking three and four thousand dollars weekly; it’s bankrupting all other

attractions; it’s a novelty; it’s a sensation; it’s the best advertised

attraction the world has ever known. For

men only; it’s a thousand miles ahead of the Kota Dance;

can give a hot speil on it. Rich and

racy for side show. Work it on stage;

can use any man or woman for subject; just stand in front of the light, let

them look through you. . . . [T]ake a nice looking lady, charge 10c. to look

through her.

The New York Clipper, September 12, 1893, page 449.

Shortly after the fair

closed, M. B. Leavitt’s “spectacular production” of “The Spider and Fly,”

featured a song about the “kouta-kouta” dancers at the Chicago World’s Fair:

Naughty

Doings in the Midway Plaisance

. . .

On the

Midway, the Midway, the Midway Plaisance,

Where

the naughty girls from Algiers do the Kouta-Kouta dance.

Married

men without their wives give a longing glance

At all

the naughty doings on the Midway Plaisance.

. . .

An old

man said, “I’d like to get an introduction there;”

He sent

his card around by way of chance,

And on

it wrote, “Oh, darling, my naughty angel fair,

Teach

me to do your ‘Kouta-Kouta’ dance.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 23, 1894, page 5.

San Francisco Call, March 21 1894.

For "Coochie-Coochie" (late-1894) and "Hoochie-Coochie (1895), and the deep history of pre-Fair "Kutchy, Kutchy" and "Hootchy, Cootchy, Cootchy, I'm the Ham-Fat Man," see PART II - the History and Etymology of the "Hoochie-Coochie" Dance.

[NOTE: This post was updated on September 4, 2017 to add reference to the newly-discovered "Princess Kuta Kuta" advertisements from Chicago in 1893 and 1895.]

[ii] The Sun (New York), January 14, 1897,

page 2.

[iii]

The “Stanley Opera Company” appears to have been a British touring company

active in India and the Far East.

Although I could find very few references to the “Stanley Opera Company”

in American sources, a British newspaper archive gets numerous “hits” for the

company; most of them references to its touring in India, with a few references

to its appearances in China and Japan.

[iv]

Mario Uchard, Mon Oncle Barbassou,

Paris, Ancienne Maison Michel Levy Freres, 1877.

[v]

Maro Uchard, My Uncle Barbassou,

London, Vizetelly & Co., 1888,

[vi] The New York Clipper, May 21, 1892, page

105.

[vii]

Ferdinand Kittel, A Kannada-English

Dictionary, Mangalore, Basel Mission Book and Tract Depository, 1894.

[viii]

“Forgotten Scandal: Omene, the Suicide Club, and Celebrity Culture in 19th-Century

America, Metmuseum.org, May 4, 2016.

[ix]

See, for example, “The

Circassian Beauty Exhibit”, Lost Museum Archive, CUNY.edu.

[x] The New York Herald, December 28, 1870,

page 2.

[xi] Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), September

27, 1884, page 5.

[xii]

See, for example, Josh Cole,

Cultural and Racial Stereotypes on the Midway, Historia, page 19 (citing Robert Muccigrosso, Celebrating the

New World: Chicago’s Columbian Expositino of 1893 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, Inc.,

1993), 164).

Thank you for this incredible research

ReplyDelete