The simile, “like taking candy from a baby,” has been used idiomatically for more than a century, as a benchmark of how easy it is to accomplish something. The idiom first appeared regularly in sports reporting, to illustrate how easy it was for one team beat up on a weaker opponent.

Sports Use

In 1904, for example, New York Giants’ fans looked forward to beating up on the Pittsburgh Pirates to win the pennant. It was an aspirational statement, the Giants having fallen short to the Bucs in 1903.

But the cartoon proved prophetic, and the Giants took the National League title that season, 19 games ahead of the fourth place Pirates. This example used “small boy” instead of “baby,” but the meaning is the same.

|

“Getting the honors. This year looks like ‘taking candy from a small boy,’” The Evening World (New York), May 9, 1909, page 9. |

The earliest example I could find (1892) used “child” instead of “baby.”

The score, Topeka 16, Pana 0, shows that Pana was not in the game yesterday at Athletic park. Topeka took the game hands down and won so easily that it was almost like a man taking candy away from a child.

The Topeka Daily Capital (Topeka, Kansas), September 10, 1892, page 4.

Examples using the now-more familiar “baby” showed up in print a few years later.

Folk also fielded and batted well. Columbus has, without a doubt, drawn a prize in this player. He is tricky too, and made Mobile give up one run yesterday in the ninth inning that seemed like taking candy from a baby.

Columbus Daily Enquirer-Sun (Columbus, Georgia), June 11, 1896.i

The Third ward kid foot ball team beat the Fourth ward team this afternoon 18 to 4. The Third warders say winning the game was like taking candy from a baby.

Arkansas City Daily Traveler (Arkansas City, Kansas), January 8, 1898, page 5.

When William Heffernan of South Africa landed in America last year he was touted as the champion welter-weight and middle-weight boxer of New Zealand and South Africa, and a man fit to do battle with the greatest glovemen of the world in those classes. [But] from the moment he put up his hands it was plain to the least critical observer that the stranger could not “make good.” Ryan laughed at him and went to work very pleasantly to put it all over Bill. . . . It was like taking candy from a child for Ryan.

The Buffalo Times (Buffalo, New York), March 22, 1898, page 1.

When the boys went to sleep on the bases he made some one hit and that man was out. It was like taking candy from a baby. It was high way robbery and he ought to be indicted.

The Iola Daily Record (Iola, Kansas), May 27, 1899, page 1.

“Like taking candy from a baby” is generally used in a positive sense, to express how easy it is to accomplish something. But the expression borrowed from an earlier line of similar expressions, generally framed in a negative sense, comparing the mean person at issue with a proto-typical mean person. One such mean person was the one who would steal acorns from a blind pig.

The “meanest man” . . . according to tradition is he who will “steal acorns from a blind hog.”

Chicago Tribune, April 6, 1890, page 34.

Precursors and early variants were used as a personal insults, shaming people who do something considered bad or evil, with unflattering comparisons to the meanest of the mean and lowest of the low, where the mean and low people were illustrated by people who would take various combinations and permutations of things of value from various combinations and permutations of types of vulnerable people.

Someone might be said to be so mean, that they would [take/steal] [something of value] from [someone who was vulnerable and/or innocent]. The thing of value might be gingerbread, licorice, cornbread, candy, money or other valuable item (or at least valuable to the person from whom it was taken). The vulnerable person might be a child or baby (frequently more specifically, a black or sick child), a blind person, a bum, a dead person or a church.

In 1830, for example, anti-Jackson partisans thought that anyone who praised Andrew Jackson was capable of much worse.

The effort upon Fulton would be useless; he is so immodest, and so lost to shame, as openly to praise Duff Green and Gen. Jackson, and he who would countenance them, would, in my opinion, rob a beggar of his rags, or steal rusty nails from a dead man’s coffin.

The Arkansas Gazette (Arkansas Post, Arkansas), September 22, 1830, page 1.

In 1837, pro-Jackson partisans thought that anyone who would ridicule Andrew Jackson was capable of much worse.

In that paper of yesterday may be seen an article copied from the Cincinnati Post, proposing, in ridicule, the erection of a statue to Gen. Jackson, presenting him in such a light as would be an outrage to the whole nation. Men who will indite and publish such articles, are base enough to open a new-made grave and steal the “coppers from a dead man’s eyes,” - meriting the execration of every American citizen.

The Mississippi Free Trader (Natchez, Mississippi), April 4, 1837, page 2.

Many of the early examples in print reflect the newspaper publishers’ attempts to shame their customers to pay their bills. An early example includes several colorful precursors to “taking candy from a baby.”

We believe the man who will cheat a printer – who will advertise his goods and nostrums in a newspaper and then refuse or neglect to pay for it, would, if an opportunity offered itself, steal pennies from a dead man’s eyes and rob his saddlebags of cold victuals. Yea, we verily believe such a man would not hesitate to steal a ‘snifter’ from a sleeping loafer’s rum-jug.

The Enterprise and Vermonter (Vergennes, Vermont), December 4, 1839, page 3.

An early example of something approaching the traditional format appeared in a British newspaper’s plea for payment (the problem of unpaid subscriptions appears to have been universal). But the specific means of insulting the subscriber may be distinctly American, as the British newspaper attributed it to an American newspaper.

An American editor states that a person who refuses to pay the printer for his newspaper would rob a church.

Liverpool Mercury, December 16, 1842, page 8.

The traditional form appeared in an American newspaper the following year, when a “man ‘out west’” upped the ante, lumping non-payment to a printer in with a laundry list of increasingly cruel acts, two of which took the traditional form.

Plagiarism.

A man ‘out west’ uses the following severe but merited language in speaking of literary theft: -- “An individual who would cabbage the literary labors of another, and attempt to palm them upon the public as the result of his own labors, would refuse to pay the printer; would steal acorns from a blind sow; would take a “n[-word]” boy’s cold pone out of his saddle bags, or even rob the grave of its dead”!!!

Richmond Weekly Palladium, September 2, 1843, page 4.

The first of those two examples, being mean enough to “steal acorns from a blind pig/sow/hog,” would become a common, idiomatic expression, long before “taking candy from a baby.”

Numerous examples appeared in print throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, and a few scattered examples appeared in print in the first half of the twentieth century.

|

The Belleville Telescope (Belleville, Kansas), April 17, 1903, page 4. |

One example even appeared in a letter to the editor as late as 1989.

Hey there, Gazette. Tell J. J. Kilpatrick, when you see him, that when stealing becomes too easy, thieves can become too inept to fall off logs or steal acorns from a blind pig.

Cedar Rapids Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), February 20, 1989, page 10.

“Like stealing acorns from a blind pig” would also be used on occasion in the positive sense, similar to“like taking candy from a baby.” In the Minto Cup lacrosse championship series in Canada in 1912, Westminster beat up on Cornwall, 15-7 in the first game and 16-6 in the second. This cartoon, illustrating the ease of Westminster’s win, was published after the first game and before the second.

|

The Province (Vancouver, British Columbia), October 5, 1912, page 10. |

As for the second of the two early examples, “taking pone/cornbread from an n[-word] boy,” only very few examples of taking pone or cornbread have been found in print. The [something of value] in most variants was something sweet, like gingerbread, or a specific type of candy, like licorice or a sugar whistle.

Taking something of value from an “n[-word)],” usually a sick baby, was common in early examples.

Was ever such impudence uttered by human lips; reader, just think of a set of rascals who would steal a pewter spoon from a “n[-word] baby,” asking honest men to deposite money in their keeping.

Vicksburg Daily Whig (Vicksburg, Mississippi), February 6, 1843, page 2.

But not every early example was problematic. Just a few years after the earliest “acorn” and “cold pone” versions, a widely reprinted story about a man who cheated a young girl out of a five cents came very close to the now-familiar expression, with “gingerbread” in place of “candy.”

“Verily, there are some persons mean enough to steal gingerbread from a baby!”

Hartford Courant (Connecticut), January 22, 1847, page 2.

Beginning in the 1850s, several widely reprinted stories returned to the racially-specific vulnerable person, generally sick, and frequently using language reflecting the casually racist attitudes of the day.

One such story was a cautionary tale about what can happen to people who cheat the printer.

The man who pays the printer was to see us to-day; he is in excellent health and find spirits, and we are told that 25 acres of his valuable land . . . . The man who cheats the printer, left town last week, in company with the woman who flogs her husband – they were joined a short distance from the town by the fellow who stole a stick of liquorice from a sick negro baby.

Plymouth Pilot (Plymouth, Indiana), May 28, 1851, page 3 (reprinted in Indiana (1851), Wisconsin (1857), New York (1857), and Pennsylvania (1873)).

A similar story made the rounds over the next couple decades. But in this case, the person who cheated the printer was painted as even lower than the others. A person claiming to be mean enough to perpetrate a number of heinous crimes against humanity suggests they are nevertheless not low enough to cheat the printer.

A subscriber in sending us a remittance for his subscription says: “I might murder my grandmother, I might flog my wife, I suppose possibly I might smother a blind baby, I know I could steal ginger bread from a sick n[-word] baby – but I have not got so low as to cheat a poor devil of a printer.” – Plum Creek Pioneer.

Lincoln County Tribune (North Platte, Nebraska), May 15, 1886, page 1 (reprinted in Kansas (1891), Idaho (1891 and 1892) and Kansas (1894).

Some of the reprinted versions added “might vote the Democratic ticket” into the things that are worse than cheating the printer.

But not every example of taking something of value from someone vulnerable compared its meanness with that of cheating a printer, and not every example was race-specific. As early as 1856, the “mean enough to” trope was used to characterize any of a number of bad things people might do.

In a story about a thief who stole quilts, blankets and a silk skirt from an old woman:

To steal a hog, after cutting its throat in the owner’s pen, is no doubt very mean; but the individual who would steal bed clothes and petticoats would be mean enough to rob a sucking baby of its gingerbread, or lick the possum fat off an old blind n[-word]’s last piece of pone.

Monongahela Valley Republican (Pennsylvania), March 7, 1856, page 2.

In a letter to the editor about a local school ordinance:

I wish to say a few words about our noble school law, to show the readers of the Courant that stealing gingerbread from a baby can be beat.

Hartford Courant, September 20, 1858, page 2.

The popular humorist, Josh Billings (a contemporary of and frequently compared to Mark Twain) noted (writing in his trademark style, using back-woods dialect/phonetic spelling):

The meanest man I ever nu was the one that stole a sugar whistle from a sick n[-word] baby, to sweeten a kup of rye coffee with.

Sioux City Register (Iowa), February 20, 1864, page 2.

In a story about watermelon thieves:

Robbing hen roosts, or pocket-picking might be called respectable compared with this. Such a man would be mean enough to commit a highway robbery on a crying baby, and rob it if its gingerbread – steal bad coppers off a collection plate – and lick the molasses of a blind n[-word]’s last pancake, that he might satisfy the cravings of his piggish appetite for dainties.

The United Opinion (Bradford, Vermont), September 21, 1866, page 2.

In an article about the sin of avarice:

The avaricious man: He won’t subscribe for a county paper. He would steal from a defenseless woman. He would filch money from a blind man’s pocket and bamboozle an orphan to get its last dollar.

Bolivar Bulletin (Tennessee), February 9, 1867, page 2.

A newspaper accused of being “radical” would rather have been, “accused of robbing a blind woman’s hen-roost, or stealing milk from a sick baby; whipping our father’s grand mother, or knocking the crutch from a palsied man. The Tennessean (Nashville), June 28, 1867, page 2.

The negative formulation of “[take/steal/rob] [something of value] from a [vulnerable/innocent person]” remained in circulation for many decades, slowly disappearing after the positive sense came into common use, and was codified in the now-familiar form, “like taking candy from a baby.”

General Use

The now-familiar idiom, “like stealing candy from a baby,” came into general use only after several years of its use in regular use in sports reporting. The earliest, non-sporting example I’ve seen is a comment from a burglar.

“I went up, and there was no third floor front hallman. It looked too easy.

“’This is like taking candy from a child,’ I thought, as I rubber-shoed down the hall in the direction of a certain suit of rooms that I had in mind - a prima donna’s suite, the key to the main door of which was in the office rack.”

Evening Star (Washington DC), December 2, 1899, page 18.

Other examples followed during the first decade of the 1900s.

The mill man who has been struggling with the problem of belt fastenings should see the lacing machine that makes a wife lace and a perfect hinge joint. As an admiring spectator at the exhibit said, when he saw how it was done, “It is just like taking candy from a baby.”

The Wood Worker, Volume 20, Number 5, July 1901, page 40.

A political example from 1902 borrowed from the language of con-artists.

“Like stealing candy from a baby,” says the bunco man, as he takes the money from Reuben. “Like stealing candy from a baby,” says the public, as Gen. Tracy takes money from Guden in return for telling him that he is still Sheriff.

Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), March 11, 1902, page 6.

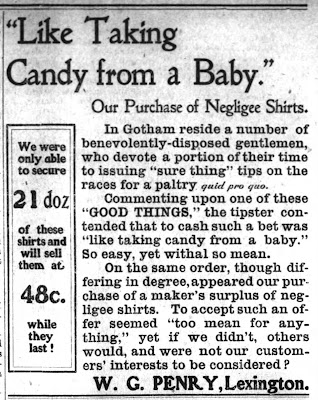

A retail example borrowed from the language of New York horse race-touts.

|

The Dispatch (Lexington, North Carolina), October 1, 1902, page 5. |

Jack London used the expression in his 1907 memoir, The Road, in describing a prison barter system he ran while serving thirty days in the Erie County Penitentiary.

Once a week, the men who worked in the yard received a five-cent plug of chewing tobacco. This chewing tobacco was the coin of the realm. Two or three rations of bread for a plug was the way we exchanged, and they traded, not because they loved tobacco less, but because they loved bread more. Oh, I know, it was like taking candy from a baby, but what would you? We had to live.

Jack London, The Road, New York, The Macmillan Company, 1907, page 101.

By 1911, the expression was so common that it was described as the “slang of the day,” in an article in the New York Times on the “Holy Ghosters” religious colony, “Shiloh,” in Durham, Maine.

The population at Shiloh numbered 200 soon after the first temple was built, and has held near that figure ever since. They represent almost all States in the Union, and several foreign countries. Many of them were well to do when they joined the colony, but their goods, chattels, and all worldly wealth is turned in for the common good. They seem to give away their farms and their bankbooks willingly, too. In the slang of the day, “it’s like taking candy from a baby.”

The New York Times, October 29, 1911, Magazine Section (Part Five), page 1.

It may be easy to take candy from a proverbial baby, but how easy is it to take candy from an actual baby?

The Mythbusters claim to have “Busted” the myth, but their “grip-strength” methodology is pretty sketchy.

You be the judge. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdutKqgmUrs

i “Meaning and Early Instances of the Phrase ‘Like Taking Candy from a Baby,’” Pascal Treguer, wordhistories.net, September 29, 2018. https://wordhistories.net/2018/09/29/taking-candy-baby/

No comments:

Post a Comment