The Grim Reality of the “Trolley Dodgers”

A History and

Etymology of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Nickname

As William Shakespeare’s Juliet

famously asked, what’s in a name? As it

turns out, what’s in the Los Angeles Dodgers’ name is quite a bit more than meets

the eye. It is well known that Los

Angeles imported the name from Brooklyn and that the name is a shortened form

of “Trolley Dodgers,” a name that hearkens back to a network of trolley lines

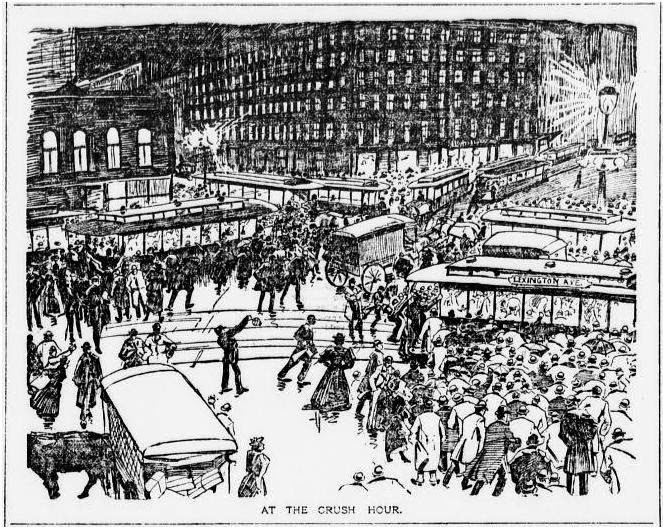

that criss-crossed Brooklyn in the 1890s; a sweetly anachronistic name that

conjures quaint images of men with big moustaches and bowler hats, women in

long, flouncy dresses and ostrich feather hats, and little boys in blue sailor

suits side-stepping cute yellow trolleys on the way to a baseball game.

The innocent-sounding name,

however, masks the grim reality. In

mid-1890s Brooklyn, trolley dodging was not merely a way of life; it was a

matter of life and death.

Little Zetta Lumberg, aged four, was this morning said to be dying at St. Mary's Hospital, Brooklyn. She was knocked down by trolley car No. 118, of the Fulton street line, last night.

As the child crossed the street at Saratoga avenue there was a maze of trolley cars and vehicles. She dodged behind an uptown car just as another trolley car came flying down the other track.

As the child crossed the street at Saratoga avenue there was a maze of trolley cars and vehicles. She dodged behind an uptown car just as another trolley car came flying down the other track.

The Evening World (New York) October 3, 1893.

The “trolley dodger” name was

first applied to the Brooklyn baseball team in 1895. Some sources incorrectly date

the first use of “trolley dodger” to 1891, when the team moved to its new

ballpark, Eastern Park, which is incorrectly said to have been surrounded by several trolley lines. In 1891, however, there would have been no need to “dodge” trolleys. All of the trolley cars in Brooklyn in 1891 were slow-moving, horse-drawn trolleys; no dodging necessary.

That would all change in 1892,

however, when the first of many electric trolley lines were installed on

Brooklyn’s streets. The new, faster,

more-powerful vehicles barreling through crowds of people raised in a horse-and-buggy

culture was a recipe for disaster. It took three years of maiming and death, a trolley strike, and a trolley reform movement for the “Brooklyns” or “Bridegrooms” (as they were known

at the time) to earn their new nickname, the

“Trolley Dodgers.”

[(For additional background, see my supplemental post,

The Introduction of Electric Trolleys

In 1881, Werner von Siemens

introduced his electric-powered tramway at the first International Exposition of Electricity in Paris (an event that would, curiously, inspire

the first-known science fiction story about an invasion

of the Earth by Martians). The first

electric trolley was tested

in the United States 1888. By 1890,

a speaker at the Convention of the American Street Rail Association noted that

of the 3,150 miles of street railroad track in the United States (trolleys and

cable cars), 2,354 miles were operated by horses, 260 miles by electricity, 255

miles by cable, 221 miles by steam, with the remaining miles being part of the

New York and Brooklyn elevated railways.

When referring to a paper on the subject of street car horses that was

to be read at the convention, he predicted that “electricity was making

such rapid strides he did not believe that at any subsequent convention the

street car horse would be considered.” St. Paul Daily Globe (Minnesota) October 16, 1890.

Brooklyn, however, still did not

have the electric trolley in 1890. The

only electric trolley service available in Brooklyn was the Coney Island and

Brooklyn line, which ran from the Brooklyn city limits at Prospect Park (then at the southern edge of the

city of Brooklyn) to Coney Island. The

neighborhoods of Flatbush, Flatlands, Gravesend and New Utrecht were all

independent towns or cities in 1890.

Flatbush, Gravesend and New Utrecht were not annexed until

1894; Flatlands was annexed in 1896.

|

| Map of the City of Brooklyn - 1889 |

Electric trolleys would quickly

encroach on Brooklyn from all sides, however. In November 1890, the New York

State Railroad Commission approved an application to switch from horse and

steam power to the “electric single trolley wire system” on the Fort Hamilton

to Brooklyn line, several lines in New Utrecht, and a line from Bay Ridge to

Gravesend Bay. The Sun (New York)

November 19, 1890. The Jamaica Electric

Railroad also had a line that terminated at the Brooklyn city limits in

1891. It was only a matter of time before

the electric trolley extended into Brooklyn proper.

In April of 1891, General Slocum, a

Civil War hero in the Battle of Atlanta (and goat at the Battle of Gettysburg),

petitioned the city for permission to build electric trolley lines on the

streets of Brooklyn. The Sun (New York) April 23, 1891. The city initially denied his request, based at

least in part on the perceived dangers of electric trolleys and their presumed negative effects on

property values:

Brooklyn taxpayers should

appear to-morrow at the Chamber of Commerce to oppose this invasion of their

streets. If General Slocum gets a

footing in Brooklyn, Deacon Richardson and Mr. Lewis, of the Brooklyn City Railway

Company, and Mr. Culver and Mr. Corbin naturally will demand and will get the

same privileges, and Brooklyn streets will be finally overrun by the worst

system of propulsion yet invented.

New York Tribune, June 10, 1891.

The Brooklyn property owners’

fears were well-founded. Electric trolleys

had already proven to be dangerous in other cities. The electric trolleys could travel at speeds of up to fifteen miles per hour, about three times faster than typical, horse-drawn traffic. The high speeds, combined with chaotic traffic patterns of the time, made life more dangerous in the streets. Newspaper accounts from before the approval

of trolleys in Brooklyn, illustrate the twin dangers of collision and

electrocution:

The third fatal accident since

the introduction of the new electric railroad system in this city [(Newark, New

Jersey)] occurred at 9 0’clock this morning.

Mrs. Mary Albrecht . . . started to cross Springfield avenue when a

downtown car struck her and threw her with frightful force against one of the

electric poles in the street. When

picked up one leg had been broken at the thigh, and her skull had been so badly

fractured that she died shortly after her admission to the German Hospital.

The Evening World (New York)

December 31, 1890;

A broken trolley wire on the

Brooklyn and Jamaica Electric Railroad was responsible for the killing of three

horses on Wednesday night. . . . William Grimms, a Woodhaven farmer, was on his

way to market in his wagon, to which two fine horses were attached. Just as they were crossing the railroad track

both horses suddenly staggered and fell to the ground side by side. . . . [A] one-horse car on the Cypress Hills road,

which uses a portion of the same tracks as the electric road, was driven up,

and the horse attached to it shared the fate of the two others. It touched the broken electric wire and fell

as if it had been struck by lightning.

The Sun, October 9, 1891.

The electric trolleys were

finally approved in early 1892:

Within a year or less a

revolution is to take place in the surface railroad system in Brooklyn by the

substation of the electric trolley system in place of horse power. . . . [T]here is very little doubt that the

resolutions will be approved by the mayor and all obstacles to the introduction

of the electric trolley in Brooklyn removed.

The Sun, December 22, 1891.

Brooklyn’s Trolley Ordinance

passed into law in January 1892 when the Mayor refused to veto the bill; he had

vetoed an earlier version of the ordinance, but it had passed over his veto. The Evening World (New York), January

23, 1892. Construction began on the

first line by mid-March, 1891. The

electric trolley would soon take over the entire city:

Brooklyn will soon be bound by

the trolley system. Nearly every surface

road in the city has made application to the Common Council and the State

Railroad Commission for the privilege of changing their motive power from

horses to the overhead electric system.

The Evening World, April 2, 1892.

|

| From thejoekorner.com |

The Death-Toll Mounts

Accidents and deaths occurred almost

immediately and the death-toll climbed steadily as the number of trolley lines

multiplied. A small sampling of

contemporary news coverage gives a sense of the danger:

“Eternal vigilance is the price

of liberty.” Eternal vigilance is

certainly needed as the price of protection from the death-dealing and hideous

trolley abomination.

The Evening World, June 23, 1892;

Another accident due to the

careless management of a trolley electric car is brought to the attention of

Brooklyn people to-day.

The Evening World, June 24, 1892;

Run into by a trolley car. This

time in Brooklyn. The record of events

keeps furnishing arguments against the perilous railway system, as applied on

city streets.

The Evening World, June 27, 1892;

The Trolley’s Fatal Score. Score three more deaths for the trolley.

The Evening World, August 22, 1892;

[A] new precaution is necessary for the suffering Brooklynite. In addition to being always

prepared to dodge the trolley wire, he must always be careful to step clear of

the trolley rail.

The Evening World, September 20, 1893;

In these times when the

trolley-cars’ slaughter from one to two people a day, the public is apt to

condemn the whole system.

The Evening World, December 20, 1893.

The trolleys were considered so

dangerous that having no accidents on the first day of operation of a new line

was apparently newsworthy:

The trolley system was put in

operation on one more of Brooklyn’s surface roads this morning. . . . This is

the first introduction of the system on Fulton street, and the swiftly moving

cars attracted a great deal of attention.

Up to noon no accidents were reported.

The system will be operated on several other roads within a few weeks.

The Evening World, November 7,

1892.

It is hard to imagine today, with

more than a century of higher-speed traffic and modern traffic laws behind us,

that the introduction of electric trolleys could create such chaos in the

streets of the mid-1890s. Early film

footage, however, provides a small glimpse of the hectic, nearly lawless

traffic patterns of the time.

|

| Fire Brigade - Brooklyn, 1893 |

|

| A Trip Down Market Street - San Francisco, 1906 |

Trolley Strike

In January of 1895, Brooklyn's trolley operators and conductors went on strike. Trolley service was interrupted completely for a time, although replacement drivers provided for limited service later during the strike. The national guard was called out, there was some violence, but in the end, management was able to break the strike after about one month.

Issues raised during the strike revealed some of the factors that contributed to the trolley dangers. Drivers complained that the trolley time-schedules were too tight, turn-around times too short, and that the schedules made it difficult for drivers to take their thirty-minute meal breaks and held them overtime, past the statutory ten-hour limit. Management's policy of firing drivers who fell behind on the nearly impossible time-schedules prompted drivers to drive at unsafe speeds.

Although the streets were made safer in the short term at the beginning of the strike, the danger mounted again as replacement drivers took over:

Issues raised during the strike revealed some of the factors that contributed to the trolley dangers. Drivers complained that the trolley time-schedules were too tight, turn-around times too short, and that the schedules made it difficult for drivers to take their thirty-minute meal breaks and held them overtime, past the statutory ten-hour limit. Management's policy of firing drivers who fell behind on the nearly impossible time-schedules prompted drivers to drive at unsafe speeds.

Although the streets were made safer in the short term at the beginning of the strike, the danger mounted again as replacement drivers took over:

The strike situation is

doubtless somewhat tedious for Brooklyn citizens, but there is at least one

consolation –while the trolley cars are not running they can’t kill

anybody. Brooklyn street know a safety

they have not known for some years heretofore, and Brooklyn mothers can see

their children start to school or to lay without the heart-straining thought

that the little ones may be brought back on a stretcher dead or maimed. . . .

It is a question, however,

whether the temporary suspension of operations by these instruments of death

will reduce the yearly returns of the murdered and maimed. It has been a bad enough killing machine in

the hands of men whom the companies’ officers have declared to be skilled and

experienced operators and whom they have paid fair wages.

Now the cars are being handed

over to new men, gathered from various parts of the country, unfamiliar, most

of them, with the trolley system, and all of them untrained in the running of

cars amid the difficulties and dangers of Brooklyn’s crowded streets; paide,

besides, less wages and less regularly employed than the men who have run the

cars in the past.

The Evening World, January 16, 1895. When the end of the strike was thought to be

near at hand, one paper reported:

. . . the Brooklyn trolley

strike is about ended. The companies

seem to be in a position to run their cars.

They are not skillfully operated, and throughout yesterday there were

many collisions, and there was much bumping together but there was no accident

of a serious nature.

|

| Dr. Octavius' Dirty Work - Spiderman 2 |

Alexandria Gazette (Virginia) January 28, 1895. Again, one day without serious

accident appeared to be newsworthy.

The following cartoon, from a trolley

strike in 1905 (with imagery seemingly inspired by Dr. Octavius in Spiderman 2),

illustrates the public’s perception of the dangers associated with strike

replacements:

|

| The Washington (DC) Times, March 29, 1905. |

A serious accident during a trolley strike in 1920 illustrates the specific danger posed by replacement drivers to fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers:

Another serious accident

occurred today on the lines of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit company, whose

employes [(sic)] have been on strike for two weeks. Two trolleys collided near Ebbets field

during the rush to the ball park this afternoon and thirty persons were

reported injured.

The Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, September 11, 1920.

When the Brooklyn trolley strike

of 1895 finally ended in late February, a gallows-humor cartoon reflected the

expectation that nothing had changed:

|

| The Evening World, February 27, 1895. |

As it turns out, nothing had changed; public backlash, however, would soon change matters.

Resistance and Reform

Within a few week following the end of the trolley strike, the public organized mass-meetings, attended by 5,000 to 10,000 people, to protest the dangers of the trolleys. The first meeting was held in early April, 1895, and continued, periodically, through May. The meetings, led by a coalition of priests, ministers, and rabbis, pressed for changes in operational policy. Their proposals included speed limits and the installation of safety fenders on the

front of

the trolleys. In May, 1895, a crowd of

more than 5000 people listened to a song entitled, “The Trolley Dirge,” in

which a clang of a trolley gong was followed by a chorus of childish

shrieks. “It is a horrible thing, but

not more so than the horrible work of the trolley which now has a record of 108

killed and over 500 more maimed for life.” Christian

Work, May 23, 1895. But the death

toll continued to rise; it stood at 133 dead by the end of the year. Christian Work, January 2, 1896.

The political response was nearly immediate. On April 14, 1895, the Mayor signed a new trolley ordinance. The new ordinance limited speeds to six miles per hour in the most crowded districts and eight miles per hour in other neighborhoods (the original electric act of 1882 had included a ten mile per hour speed limit, but due to the lack of any speed indicator and the failure of enforcement, speeds had routinely been higher), created a team of trolley inspectors to enforce the speed limits, and required the use of fenders on the trolleys. In May, several trolley executives lost their jobs for their part in contributing to the trolley dangers, and in August, the city instituted criminal proceedings against trolley executives who had violated the statutory, ten-hour shift for trolley car operators.

The political response was nearly immediate. On April 14, 1895, the Mayor signed a new trolley ordinance. The new ordinance limited speeds to six miles per hour in the most crowded districts and eight miles per hour in other neighborhoods (the original electric act of 1882 had included a ten mile per hour speed limit, but due to the lack of any speed indicator and the failure of enforcement, speeds had routinely been higher), created a team of trolley inspectors to enforce the speed limits, and required the use of fenders on the trolleys. In May, several trolley executives lost their jobs for their part in contributing to the trolley dangers, and in August, the city instituted criminal proceedings against trolley executives who had violated the statutory, ten-hour shift for trolley car operators.

|

| A trolley with safety fenders attached. |

The cities of Baltimore and Buffalo, which were both early adopters of trolley fenders, reported success in reducing the rate of injury. Brooklyn began installing fenders in July of 1895. The Evening Star, July 6, 1895. Peninsula Enterprise (Accomac, Virginia) September 7, 1895. In Philadelphia, the safety fenders may have been too successful:

The

fun of dodging trolley cars, which has added so much to the agility of

Philadelphians during the last couple of years, has just been augmented

by the positive delight of falling in front of them. Small boys are

whitening the hair of every motorman in town by dropping unexpectedly in

front of the cars just for the exhilarating experience of being tossed

in the bed of a fender.

Shenandoah Herald (Woodstock, Virginia) October 11, 1895.

By August of 1896, there were no longer any electric trolleys in the United States that operated at speeds in excess of ten miles per hour. Western Electrician, August 15, 1896.

But speed limits, fenders and inatentive operation were not the only problems with electric trolleys. Another major problem was the complete lack of traffic safety standards or universal rules of the road. Mid-1890s Brooklyn, and everywhere else for that matter, did not have traffic codes. The slow pace of the horse-and-buggy culture had simply never needed any standardized traffic rules. The faster, more powerful electric trolleys, and later the automobile, would eventually lead to the introduction of standardized rules of the road that helped ameliorate the dangers of the new technologies.

By August of 1896, there were no longer any electric trolleys in the United States that operated at speeds in excess of ten miles per hour. Western Electrician, August 15, 1896.

But speed limits, fenders and inatentive operation were not the only problems with electric trolleys. Another major problem was the complete lack of traffic safety standards or universal rules of the road. Mid-1890s Brooklyn, and everywhere else for that matter, did not have traffic codes. The slow pace of the horse-and-buggy culture had simply never needed any standardized traffic rules. The faster, more powerful electric trolleys, and later the automobile, would eventually lead to the introduction of standardized rules of the road that helped ameliorate the dangers of the new technologies.

In 1903, New York City (including Brooklyn, which had been

annexed in 1898) adopted the first set of modern traffic codes. The codes had first been proposed by William Phelps Eno

(who later worked on traffic codes for London and Paris) in 1901. His proposals included such revolutionary

ideas as, keeping to the right, passing on the left, making right turns from

near the right curb and left turns from near the middle of the street, and

signaling before stopping or slowing.

Interestingly, his suggestion for the signal before stopping or slowing

was to raise the buggy whip. The New York

Tribune, February 4, 1900. He

believed that enacting, following and enforcing a few simple traffic rules

could eliminate ninety percent of all traffic accidents. The now ubiquitous and indispensible stripe down the middle

of the road was invented in 1911 and the first traffic lights in

1912, although neither were widely adopted until years later.

It must have been an incredibly

difficult transition for a horse-and-buggy culture to adapt to the presence of

large, mechanical machines (first electric trolleys and later automobiles) running

down the middle of their streets. Change

was slow. An indication of the slow pace of change is a

report from the June 15, 1918 issue of Good

Roads magazine that St. Louis was considering the noteworthy step of making

pedestrians, as well as vehicles, subject to the traffic code. Brooklyn

in the mid-1890s was just beginning to deal with the changes and was

paying the price that would eventually lead to much-needed reforms.

Trolley Dodgers

The name “trolley dodgers”

first appeared in print in early May of 1895:

The “Rainmakers” and the

“Trolley Dodgers” are the latest terms used by base ball writers to designate

the Phillies and Brooklyns respectively.

The Scranton Tribune, May 11, 1895.

The reference to the “Rainmakers” appears to have been a reaction to a

suggestion by a New York sportswriter less than two weeks earlier that, “[f]rom

now out the Philadelphias will be known as the “Rainmakers” in Gotham.” The World (New York) May 1, 1895. The name appears to have been prompted by a series of rain-outs of games with scheduled with the

Phillies. The reference to the “trolley

dodgers” also appears to be a response to a newly minted nickname.

Barry Popick’s etymology blog, The

Big Apple, cites one earlier reference to “Trolley Dodgers” from the

previous week:

“Trolley dodgers” is the new

name which Eastern baseball cranks [(fans)] have given the Brooklyn club.

The San Francisco Chronicle on

May 4, 1895. The fact that two, independent

sources report that the name is “the latest term” or “the new name” suggests

that the name was new, and unfamiliar to sportswriters (and likely their

readers) at the time. Clearly someone

had used the name before the San Francisco papers picked it up on May 4, 1895,

but probably not long before. Although

1895 was long before the “information age,” they did have the telegraph that

permitted nearly instantaneous dissemination of news, so a sportswriter who

followed baseball would be familiar with developments in the game soon after

they happened.

Several other sources would

repeat the news of Brooklyn’s new name throughout the rest of the season, using

precisely the same language (“‘Trolley dodgers’ is the new name which Eastern

baseball cranks have given the Brooklyn club”), indicative of novelty, as had

been used in the San Francisco article.

See, e.g. Atchison (Kansas) Daily

Globe, August 30, 1895; Warren (Pennsylvania) Ledger, September 3, 1895; The Roanoke Times (Virginia) September 13, 1895. The repeated reporting that the name was new,

in so many different outlets, suggests that the name was, in fact, new in 1895

and had not been known or used during the previous season. The name was still new enough in 1896

baseball season, that a magazine piece explained:

As a playful descriptive term

for the members of the Brooklyn Baseball club, the name “Trolley-dodgers” has

been adopted by some of the New York papers.

Western Electrician, August 29, 1896.

The name, "Trolley Dodgers," however, had already achieved widespread, frequent use in many different newspapers during the 1896 season. It was also used as the name for the Brooklyn Skating Club’s hockey team in 1897, in the earliest non-baseball use of the term that I could find. The Sun, February 6, 1897. Unless earlier uses are discovered, it seems safe to say that the name probably originated near the beginning of the 1895 season. In any case, it seems certain that the name could not have arisen prior to the introduction of electric trolleys in 1892.

A biography of physicist Nicola Tesla, who worked with Edison on electrical power generators in New York in 1885, asserted, without citation, that the name "trolley dodger" had been adopted by a group trolley protestors. Margaret Cheney, Tesla: Man Out of Time (1981), page 33. Although the timing of the appearance of the name in May, 1885, during the high-point of trolley reform activism, is consistent with the claim, I found no clear evidence of the name used in any of the contemporary accounts of the anti-trolley meetings.

The name, "Trolley Dodgers," however, had already achieved widespread, frequent use in many different newspapers during the 1896 season. It was also used as the name for the Brooklyn Skating Club’s hockey team in 1897, in the earliest non-baseball use of the term that I could find. The Sun, February 6, 1897. Unless earlier uses are discovered, it seems safe to say that the name probably originated near the beginning of the 1895 season. In any case, it seems certain that the name could not have arisen prior to the introduction of electric trolleys in 1892.

A biography of physicist Nicola Tesla, who worked with Edison on electrical power generators in New York in 1885, asserted, without citation, that the name "trolley dodger" had been adopted by a group trolley protestors. Margaret Cheney, Tesla: Man Out of Time (1981), page 33. Although the timing of the appearance of the name in May, 1885, during the high-point of trolley reform activism, is consistent with the claim, I found no clear evidence of the name used in any of the contemporary accounts of the anti-trolley meetings.

“Trolley Dodger” as a Term for a Resident of Brooklyn

There are no known examples of

the term “trolley dodger” being applied as a general euphemism for Brooklyn

residents prior to 1895. The verb, “to

dodge,” however, appears with some frequency:

Brooklyn’s trolley cars made a

field day of it yesterday. There was a

collision, which incomprehensibly failed to kill anybody, and there was the

killing of an eight-year-old boy, who

couldn’t dodge a car under full headway.

The Evening World, July 11, 1892;

In addition to being always prepared to dodge the trolley wire,

he must always be careful to step clear of the trolley rail.

The Evening World, September 20, 1893; in a report about two

Irishmen (I think I learned a song like that in grade school) who were hit by a

trolley, written in a manner to suggest an Irish brogue:

We were dodgin’ the dorned throlleys at every corner, and couldn’t get

clear of thim. We will never go near

Brooklyn again.

New York Tribune, November 27, 1893; in a one-liner joke:

“There’s no use in talking,”

remarked a man who had just dodged a

broken trolley wire; “even in this country a man must show respect for

lineal descent.”

The Evening Star (Washington DC) January 29, 1894; in an article

about a fat policeman who was outrun by a woman who was avoiding a trolley:

As for the fat policeman, he dodged off the track, mopped his brow,

and observed; “Well, if women don’t beat the devil!”

The Sun, March 18, 1894; in a satirical article about the

advantages of Brooklyn as a vacation destination;

Dodging

trolley cars,

I may say in conclusion, is, after all, great fun, and is much less dangerous

than football.

The Sun, September 30, 1894; in an article about the life of an old

man from the country who has not spent time in the city;

He hasn’t had to dodge trolley or cable cars, or live in

2x2 flats, or lie awake Saturday nights wondering if a side door will be open

on Sunday.

The Evening World, December 17, 1894; in a humor piece that

imagined how Napoleon Bonaparte would react during a visit to modern-day New

York City:

Dodging

a trolley car. Mr. Bonaparte (loquitur) – Sacre! This is

worse than the Russians.

The Washington Times, March 24, 1895; in an article about

Brooklyn’s postmaster Sullivan, who had arranged for mail to be delivered

continuously through the day using the electric trolley system:

Uncle Sam “would be too busy dodging trolley cars” in Brooklyn to

tip his hat to postmaster Sullivan.

St. Paul Globe May 27, 1895;

Kansas City (Missouri) Journal, May 19, 1895; with the introduction of more cable cars in

mid-town Manhattan, the streets of New York were also becoming more dangerous:

People seldom kill themselves in the city of Brooklyn. When they get tired of life they simply quit dodging trolley cars.

Cable car dodging at this point

bids fair to become as prominent a feature of metropolitan life as trolley car dodging is in Brooklyn.”

The Sun, October 20, 1895.

|

| The Sun, October 20, 1895. |

Despite frequent references to

dodging trolleys, there were no references to a “trolley dodger.” It would not be a stretch, of course; someone

who dodges trolleys might easily be called a trolley dodger. But as easy as it would have been to coin and

use the phrase before 1895, there is no record of any such use. The term seems to have been coined in early

1895, whether by a sportswriter with reference to the baseball team, a group of trolley protestors, or organically based on the common association of Brooklyn with dodging trolleys.

The earliest reference that I could find using "trolley dodger" in a non-sporting context was a joke that appeared in the June 3, 1897 edition of The American Stationer. The narrator of the joke is described as a,

“young ‘Trolley Dodger’ (misnomer for Brooklynite),” who is attending a Quaker

church service with his best girl. To

lighten the mood, he tells her a humorous story about what had happened at an

early Quaker service. The story revolves around a “son of ‘Ould

Oirland,’” presumably Catholic, who is unfamiliar with the rituals of a

Friends’ Meeting House, which, as related in the joke, involve parishioners

jumping out of their seats to shout when, “the spirit moved.”

“Trolley dodger” is used here in a neutral,

certainly non-pejorative, sense. Placing

the narrator in Brooklyn may have been designed to account for the presence of

an Irishman at a Friends’ Meeting House; Brooklyn being home to a large Irish

immigrant population. Other non-sports

related references to “trolley dodger” from after 1897 similarly lack a

pejorative tone. The phrase seems to

have been embraced by Brooklynites, and never really understood as an insult.

Conclusion

The name “trolley dodgers” would

not and could not have been used to describe the baseball team or anyone else

from Brooklyn until 1892. The frequent appearance

of the verb “to dodge,” in association with trolleys in Brooklyn between 1892 and 1894, and the lack

of evidence of “trolley dodger” during the same period, suggests that the

phrase had not achieved a significant level of use, if any at all, before

1895. The description of "trolley dodger" as the "new" name of the Brooklyn team shortly

after opening day in 1895, and the repeated reporting of the name as “new” throughout 1895 and into 1896, suggests that the name was likely first applied

to the team in 1895. The name seems to

have been extended to people from Brooklyn only later, and then not in a pejorative

sense.

The dark history of the Dodgers

name should not caution against embracing the name. Instead, the courage and persistence of our

Brooklyn forbears in facing, surviving, and ultimately taming the trolley

menace should elevate our appreciation of the name, “Dodgers,” from a sweetly

anachronistic, dated vestige of an earlier age (like the Padres or Brewers) to

that of a proud, heroic figure, more like the Pirates and Braves.

Go Dodgers!!!

OK, I’m not going to leave you

hanging. If you are curious about the

1897 “trolley dodger” joke, here it is in all of its glory:

A young “Trolley Dodger”

(misnomer for Brooklynite) was taking his best girl to church Sunday night

last. It was to a Friends’ church, and

to relieve the monotony of the occasion and to make his remarks apropos to the

time as well as himself interesting to his companion he told her the following

store: The scene is laid in a Friends’

meeting. All were according to custom

waiting for “the Spirit to move.” At

last, at last, I say, a member of the sect jumped from his seat and exclaiming

“I am married!” sat down. Whereupon an

Irishman, who was present for the novelty of the thing or by mistake, shouted

out, “The d—d you are!” Then all was as

quiet as the soul when the spirit has departed.

Soon the same Friend was again touched by the Spirit, and by bounding

from his seat he fervently shouted, “I am married, I am married to a daughter

of the Lord,” and down he sat again.

Then the wit of the son of “Ould Oirland” came into play, and moved by

an entirely different spirit he jumped up and said: “Say, mister, if thot’s

the’ case it’ll be er long toime afore yer see yer father-in-law.”

No comments:

Post a Comment