The trolley car wire came down to the ground,

And laughed in ghoulish glee,

And said: “I guess you fellows have found

That you can’t play horse with me.”

-- Philadelphia Inquirer.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 8, 1895, page 6.

The Los Angeles Dodgers’ nickname is short for “Trolley Dodgers,” a vestige of their origins in Brooklyn, where new-fangled electric trolleys killed hundreds of pedestrians during their first years of service. Brooklyn began construction of its electric trolley system in 1891. The name first appeared in print early in the 1895 season.

Brooklyn players are now known as trolley dodgers, and probably Dave Foutz is looked upon as the trolley pole, remarks an exchange. (Season started april 18 – versus Giants).

Brooklyn Times Union, April 26, 1895, page 6.[i]

Early Sports ‘n’ Pop-Culture History Blog has previously posted a full history of the circumstances surrounding the dangers of the new trolley system and its relation to the new name. See, “The Grim Reality of the Trolley Dodgers.” https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2014/04/the-grim-reality-of-trolley-dodgers.html.

It has long been assumed that the name, as applied to the team, was borrowed from a local nickname for people from Brooklyn, generally. But the evidence was inconclusive.

Dodging electric trolleys was in the news in Brooklyn as early as 1892.

Brooklyn’s trolley cars made a field day of it yesterday. There was a collision, which incomprehensibly failed to kill anybody, and there was the killing of an eight-year-old boy, who couldn’t dodge a car under full headway.

The Evening World, July 11, 1892).

But the earliest example I had found of the nickname, as applied to residents of Brooklyn generally, was from 1897, two years after first use of the team nickname, leaving open the question of which came first, the team name or the local nickname.

New evidence, however, may provide an answer. In January of 1893, a comedian named Frank Moran addressed an audience in Cincinnati as his “beloved trolley-wire dodgers.”

Frank Moran addressed the audience at The People’s last week as “My beloved trolley-wire dodgers,” and he came near calling the turn.

Cincinnati Enquirer, January 8, 1893, page 19.

Frank Moran had appeared at Hyde & Behman’s Theater in Brooklyn a few weeks earlier and would return to Brooklyn to perform at the Gayety Theater a few weeks later.

Moran was a “topical” orator, whose act borrowed from local politics and events in whatever city he appeared. Cincinnati had had an electrical trolley system since 1890, and Brooklyn was in the process of expanding its electric trolley system. Both Cincinnati and Brooklyn had recently had accidents related to the trolley-wire, so he may have used the same expression in his act in both cities.

While it is possible that Moran originated the expression, it is also possible that he learned it in Brooklyn and added it to his act. Although it may be impossible to identify with any certainty who coined the expression, or when, it seems likely that “trolley dodgers,” or at least “trolley-wire dodgers,” was known in Brooklyn two years before the name was first applied to the baseball team. Frank Moran could have coined the expression, but even if he didn’t, he may have helped popularize the expression through his many appearances in Brooklyn.

Moran may have used the expression in every city he visited dealing with the dangers of their new electric trolley systems. The name took root and flourished in Brooklyn, in part because Brooklyn would expand its trolley system into the most extensive electric trolley systems in one of the most densely populated cities, and in part because of its location near the culture and media center of New York City, which could amplify the use of the name in nearby Brooklyn.

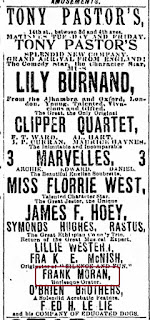

Frank Moran

Frank Moran was a well-known blackface minstrel and comedian. He was frequently described as an “orator,” and sometimes billed as a “burlesque orator.” He was best known for his political “stump speeches,” giving rise to his nickname, “Senator” Frank Moran.

|

| The New York World, May 7, 1893, page 23. |

His act appears to have consisted of a mix of old and new jokes. In 1893, he was described as having “uttered the same ‘stump speech’ for 30 years.”[ii] Yet his material was “topical,” reflecting “The Situation” in whatever city he was performing; the Daily Show with Frank Moran, if you will.

Hyde and Behman’s Theatre.

Harry Williams’ Own Specialty Company was the magnet which drew great audiences to Hyde and Behman’s Theatre yesterday afternoon and last night. . . . Senator Frank Moran, the popular topical orator, showed that he was well posted on events in this city, during his quarter of an hour talk, on “The Situation.”

Brooklyn Standard Union, November 14, 1893, page 2.

Hyde & Behman’s Theater.

Harry Williams’ company contains many performers well known to followers of the vaudeville. . . . Frank Moran makes allusion to Brooklyn politics and institutions which are more or less acceptable.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 14, 1893, page 5.

How everybody did laugh at the local hits on the recent election made by “Senator” Frank Moran, whose negro stump speech was one of the most delightful features of the performance. Comedian Moran has won the title of “senator” on his ability as a stump orator.

The Boston Globe, November 13, 1894, page 4.

His brand of political humor was apparently popular in Philadelphia.

Frank Moran delivered a side-splitting stump speech advocating a tax on immigrants. . . .

The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 17, 1894, page 5.

But it wasn’t universally appreciated; at least not in New Orleans.

The stump speech of Mr. Farnk Moran, of the minstrels, is said to be the funniest thing ever heard in Philadelphia. As soon as the people here understand it they will laugh at it. In the meantime he must be patient.

New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 3, 1883, page 2.

Even in Brooklyn, where he returned year after year, his caustic humor rubbed some people the wrong way; at least the class of people who filled the tightly-packed boxed seats.

Frank Moran, who delivers stump speeches at Hyde and Behman’s Theatre, should consider that audiences have some rights. The class of people who occupy private boxes at the Adams street theatre do not care to be designated as “sardines.” Mr. Moran is long enough in the business to know the difference between playing in Brooklyn and Yapville.

The Brooklyn Citizen, November 30, 1892, page 2.

A few days after insulting the “better” class of people in Brooklyn, he left for an engagement in Philadelphia.

The illustrious “Senator”Frank Moran will distinguish himself on popular topics of the day. As a black-face orator he is without an equal.

Philadelphia Inquirer, December 4, 1892, page 11.

Frank Moran would be back in Brooklyn within two months, for a stint at the Gayety Theater beginning January 30, 1893.[iii] Between his stops in Philadelphia and Brooklyn, he made a swing out West, including a stop in the “Queen City” of Cincinnati (also known at the time by the less euphonious, alternate nickname, “Porkopolis”).

Cincinnati Electric Trolley System

Frank Moran was a big hit when Harry Williams’ Own Specialty Company opened a one-week engagement at the People’s Theater in Cincinnati on January 1, 1893.

The attraction at the People’s Theater this week is Harry Williams’ Own Specialty Company. . . . Frank Moran, the premier stump orator, put the audience in roars of laughter.

Cincinnati Enquirer, January 2, 1893, page 5.

One week later, a reviewer recalled one of the jokes that had helped elicit those laughs; he had addressed the audience as “my beloved trolley-wire dodgers.”

Cincinnati audiences were familiar with the dangers of electric trolleys. The city had had an electric trolley system for at least three years,[iv] and had experienced multiple recent tragedies in which electric trolley-wires had been a factor.

TEAM OF HORSES

They started over Eighth street, and were just crossing Walnut street when one of the trolley wires of the Colerain avenue line broke and fell over the horses’ backs. They received a terrible shock, and became crazed with their pain and fright. They plunged forward, and the wire next struck Coachman Hutchinson in the face. He was nearly paralyzed by the shock and threw up one hand to get the wire over his head, while with the other he tried to hold the horses.

The wire went over the coachman’s head and struck Dr. Whittaker, catching him under the jaw. The horses then gave a frantic plunge forward. The wire twisted around the hub of the vehicle, and all the occupants were hurled to the street. Dr. Whittaker was dragged over the top of the Victoria and fell stunned and bleeding on the street. Miss Joy was thrown out on the left side, and was picked up under an express wagon that was standing near the scene of the accident.

The Cincinnati Enquirer, October 27, 1892, page 4.

And even when not directly involved in an accident, the mere existence of trolley wires could create dangerous situations. On January 6, 1893, during the course of Frank Moran’s run at the People’s Theater, three men died of injuries in an incident caused, in part, by electric trolley lines interference with a railroad safety gate.

Three men died when crossing the railroad tracks as two steam locomotives passed in opposite directions at the Queen City Avenue crossing. A crossing guard shouted a warning, but the victims didn’t respond. The accident might otherwise have been prevented by a safety gate that would have barred crossing, but the gate had been “taken away, as the poles when raised hit the trolley wires.”[v]

The Queen City Avenue railroad crossing, the scene of the deadly railroad accident claiming three lives in Cincinnati on January 6, 1893. The Queen City Avenue trolley tracks and overhead trolley-wires can be seen crossing the tracks. The Cincinnati Enquirer, January 7, 1893, page 1.

Two years later, residents of Cincinnati were still dodging trolley-wires.

A broken trolley wire caused no little excitement among the passengers and for a time rendered the position of a motorman on an East End electric car decidedly uncomfortable yesterday afternoon. The car was proceeding along Eastern avenue in the direction of the city when one of the trolley wires broke and fell dangling into the vestibule of the car, emitting flashes of fire whenever it came in contact with the wood or iron-work. The motorman was kept busy dodging the live wire, but escaped uninjured.

Cincinnati Enquirer, March 28, 1895, page 10.

Trolley-Wires

My previous post about the origins of the name of the Los Angeles Dodgers focused primarily on the dangers of relatively “high speed” collisions (by 1890’s standards) with electric trolleys. But this early use of “trolley-wire dodgers” suggests that the dangers of electrocution from trolley wires may have been at least as much of a concern at the time. Contemporary accounts of trolley-wire accidents shed light on what it was like to deal with the dangers of adapting to the new technology.

One of the team of William Kelly, a contractor . . . drawing a truck and driven by John Moran, was touched by the end of the broken wire and received a shock that made it plunge with pain and fright.

A conductor who tried to remove the wire by using his doubled up coat as a guard also received a shock.

The wire was finally removed by the united efforts of the conductors and drivers of ten stalled cars. They lassoed the end of the wire with a rope and then fastened it securely to a post.

The New York Evening World, May 2, 1894, page 1.

A loose trolley-wire could cause injury even when it didn’t electrocute anyone.

[T]he trolley wire, the petitioner alleges, being in poor condition, broke and let the pole fall on the cars, “making,” the petitioner says, “a loud, crackling noise, and encircling the cars with vivid flashes of light.” As soon as the wire fell, and before the motor car stopped, the motorman left his place and ran to the rear end of the car, crying to Mrs. Harrington in a loud voice: “Look out for the live wire!” He then jumped in an excited manner to the ground. Mrs. Harrington, it is alleged, was put in great fear by the cries and action of this man, and by the loud noise and vivid flashes of light caused by the wire; and believing her life to be in danger If she remained on the car, she impetuously attempted to alight from the car, and was hurled to the ground, and received a fracture of the bones in her left foot, besides spraining her left ankle, bruising her left arm, and greatly shocking her nervous system.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 5, 1894, page 12.

And even when they weren’t loose, overhead wires were still something that had to be dodged, at least by people sitting on top of a horse-drawn carriages.

All hands then boarded the tally-ho [coach] and the homeward journey was begun. George Mason held the ribbons, and dexterously guided the prancing steeds, while “Billy” Blackford, who sat beside him, was kept busy dodging trolley wires and electric sparks.

Ironically, when citified women of the 1890s grew accustomed to the dangers of the new technology, they apparently developed fears of more innocuous things not encountered in the city.

She does not heed the cable car

Which goes with speed intense;

She cares not for the trolley wire

Whose voltage is immense.

The old excursion steamer brings

No terror to her brow,

But when she’s in the country she will run across acres of ground and climb barb wire fences to escape the affable though inquisitive gaze

Of an aged, docile cow.

-- (Washington Star.

Buffalo Courier, August 14, 1894, page 4.

Calling the Turn

The final piece of the puzzle, in deciphering Frank Moran’s “trolley-wire dodgers” comment, is the archaic idiom, “to call the turn.” “To call the turn” could mean either, “to make an accurate guess, estimate, or prediction,” or “to pick a suspect out of the police line-up and formally identify him as guilty of a crime,”[vi] or more simply, “to solve a problem, identify a criminal.”[vii] The expression is believed to have been derived from “calling the next turn of the wheel in the game of Faro.”[viii]

Examples of both senses of the expression, from the same period, may provide some insight into how it was used.

Men in positions of trust become defaulters, and men once wealthy are driven to penury in the hope of “calling the turn” on the unreal price of certain commodities as fixed from time to time by other gamblers of greater resources. The glittering temptation seduces men from every walk of life.

Galena Weekly Republican (Galena, Kansas), December 28, 1883, page 6.

Some technical purists are calling the turn on people who say “the United States is a nation,” alleging that it is bad grammar, and that we should say “the United states are a nation.”

Logansport Pharos-Tribune, July 28, 1893, page 18.

But what did the Cincinnati reporter mean in saying that Frank Moran “came near calling the turn,” when addressing his audience as “trolley-wire dodgers”? Did he mean that the name was nearly an accurate characterization of the audience, or that in calling out the trolley-wires he nearly identified the trolley company as the true culprits? We may never know.

Conclusion

But what we do know, is that the expression “trolley-wire dodgers” predates the first use of “trolley dodgers” as the nickname of Brooklyn’s professional baseball team (now the Los Angeles Dodgers) by more than two years. The expression may have been coined by the blackface comedic “orator,” the “Senator” Frank Moran. And even if Moran did not coin the expression, he may have used it in his act in Brooklyn in late-1892 or early-1893, which could have helped popularize the expression in Brooklyn, where trolley accidents and deaths were a tragic part of life during the early years of the electric trolley.

Go Dodgers!!!

[ii] Omaha Daily Bee, January 30, 1893, page 5.

[iii] The Brooklyn Standard Union, January 31, 1893, page 4.

[iv] The Cincinnati Enquirer,January 5, 1890, page 2 (“Guarding Against Accident. City Electrician French has recommended to the B. P. A. that guard wires be placed over all electric road trolley wires to prevent further accident to telephone and telegraph lines.”).

[v] The Cincinnati Enquirer, January 7, 1893, page 1.

[vi] Dictionary of American Underworld Lingo, New York, Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1950, page 39.

[vii] Eric Partridge, Slang To-Day and Yesterday, New York, Routledge, 2015 (reprint of original, published in 1933).

[viii] Jonathan Green, Cassel’s Dictionary of Slang, 2nd Edition, London, Weinfeld and Nicolson, 2005.

No comments:

Post a Comment