The History and Etymology of “White Elephant” Gift Exchanges,

"White Elephant Sales" and “Yankee

Swaps”

“White elephant” gift exchange

and “Yankee swap” are two different phrases for the same event; a party in which a number of people exchange gifts, with the opportunity

of swapping gifts in an effort to get a better gift. A “white elephant” is a possession that is

not worth the trouble of keeping; so in a “white elephant” gift exchange, the

more useless or funny the gift is, the better.

Hilarity ensues.

Although the two expressions mean, more or less, the same thing, they have separate, independent

origins; origins that are also separate and independent from the origins of the group gift exchange

party.

The “swap party” or “swapping

party” dates to at least 1901, and perhaps earlier. They were not known as “white elephant

parties” or “white elephant swaps” until about 1907, even though the

expression, “white elephant,” had been around since about 1851. The expression, “Yankee swap” may be even

older than “white elephant, but that term was not applied to “swap parties” until

well into the twentieth century.

Swapping Yankees

The expression “Yankee swap”

relates to the reputation of “Yankees” to trade. Depending on the time and the context, the

word “Yankee,” could be applied to New Englanders, Easterners, Northerners, or

Americans. In 1855, Walt Whitman wrote a

glowing review (anonymously) of his own collection of poetry, Leaves of Grass. In the review, Whitman lists the “Yankee

swap” as one of the “essences of American things,” right up there with George

Washington and the Constitution:

. . . the essences of American

things . . . the sturdy defiance of ’76, . . . the leadership of Washington,

and the formation of the Constitution – the Union always calm and impregnable –

the perpetual coming of immigrants - . . . the noble character of the free

American workman and workwoman – the fierceness of the people when well-roused

– the ardor of their friendships – the large amativeness – the Yankee swap . .

. .

The United States Review, Volume V (September, 1855), page 205 (see

also Carolyn Wells, Rivulets of Prose:

Critical Essays, New York, Greenberg, 1928, pages 1-7).

In 1825, a Scottish magazine

published an outsider’s perspective of the New England Yankees’ propensity to

swap:

Every thing is a matter of serious

calculation with your genuine Yankee. He

won’t give away even his words – if another should have occasion for them. He will “swap” any thing with you; “trade”

with you, for any thing; but is never the man to give anything away, so long as

there is any prospect of doing better with it.

If you put a question, to a New Englander, therefore; no matter what –

no matter why – beware how you show any solicitude. You will make a bad bargain, if you do. He is pretty sure to reason thus; generous

and kind as he is, in some things. – “Now; this information is wanted. It must be of some value to him, that wants

it; else why this anxiety? – Of course, it would be of some value to me, if I

knew how to make use of it, properly. At

any rate (a favourite phrase, with him); at any rate, he wants it; he knows the

value of it; he can afford, of course, to pay for it; and will not give more

than it is worth. Therefore I shall get

as much as I can: if he gives too much for it; whose fault is that? – His; not

mine. Therefore, he shall have it; if he

will – at any rate.”

John Neal, Brother Jonathan: or, The New Englanders, in Three Volumes. William

Blackwood, Edinburgh, 1825, page 151.

The expression, “Yankee swap,”

was still in use in the early 1900s:

In certain parts of the country small

farms are now offered in exchange for moderate quantities of hard coal. A Yankee “swap” between agriculture and

anthracite!

Chicago Eagle, October 18, 1902.

Swap parties started receiving

frequent notice in the press, beginning in 1901, but were not called Yankee

swaps until much later.

White Elephants

The expressions “white elephant”

and “gift of a white elephant” date to the middle of the nineteenth

century. The expressions are based on

the historical reverence for the rare “white elephants” (naturally occurring albino

elephants), in certain cultures in Southeast Asia. The phrase, “gift of the white elephant,” is

based on the mistaken notion that Southeast Asian kings would give white

elephants as gifts to rival courtiers, in order to financially burden them with

the expensive upkeep of a sacred white elephant. You can read a more thorough review of the

history and etymology of, “white elephant” and “gift of the white elephant,” in

my earlier posting, “Two-and-a-half

Idioms – the History and Etymology of “White Elephants.”

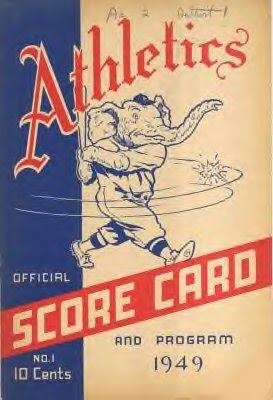

In 1902, the new manager of the

New York Giants baseball team called the Philadelphia Athletics baseball team a

“white elephant” because, he claimed, it was losing money every year. When the Athletics played the Giants in the

1905 World Series, the Athletics remembered the insult, and adopted the phrase

as an unofficial nickname.

Although the phrase, “white

elephant,” was a well-established, familiar idiom in 1901 when swapping parties

came into vogue, those parties were not called “white elephant parties” until

at least six years later.

Swapping Parties

Swapping parties, or swap

parties, became a popular social function during the early years of the

1900s. The earliest description of a

“swap party,” from 1901, describes an event very similar to the modern “white

elephant” gift exchange or “Yankee swap”:

Swap Party. Have you ever been to a

“swap” party? Each one is supplied with four or five little bundles, wrapped so

that no one else can suspect the contents.

The Hartford Herald (Hartford, Kentucky), January 23, 1901.

Soon, the national press picked

up on the craze. A 1901 article in Table Talk provided instructions for

hosting the perfect, “Swap Party”:

In this day of craze for novel

entertainments the more nonsensical the scheme the greater the enjoyment

seemingly. As illustration the function

very inelegantly designated as” The Swap Party.” Why not the word “exchange” instead nobody

knows, but at all events it has become very popular alike with old and

young. Every guest brings four or five

little neatly wrapped and tied bundles.

The more misleading in shape as to contents the better. The packages may contain anything from candy to

soap, starch, tea, book, handkerchief, sun-bonnet, etc., the more absurd the

funnier. Each person recommends their

own bundles describing the contents as wittily and in a way to deceive as much

as possible. The bargaining becomes very

shrewd and merry until all the parcels have been swapped, oftentimes more than

once. Then they are opened, the best

bargain winning first prize, the poorest compelling the holder to tell a story,

suggest a game, sing or recite for the entertainment of the company. The universal verdict – “no trouble and lots

of fun!”

Table Talk, Volume 16, Number 3, March, 1901, page 95. This description, from Table Talk, later

appered in Mrs. Burton Kingsland’s, The

Book of Indoor and Outdoor Games, With Suggestions for Entertainments (New

York, Doubleday, Page & Company, 1904, page 127).

John T. McCutcheon

wrote a humor piece about a swap party in the fictional, small Midwestern town

of Bird Center, Illinois. McCutcheon wrote

a series of Bird Center cartoons and articles for the Chicago Tribune. The stories

were similar in tone and content to Garrison Keilor’s Lake Woebegon stories;

they took place in a fictional town, with recurring, colorful characters, and

offered a satirical, yet nostalgic, view of small-town life. His “swap party” piece was included in a

collection of his Bird Center pieces that were published in book form (Bird Center Cartoons, A Chronicle of Social

Happenings at Bird Center, Illinois, 1904, Chicago, A. C. McClurg &

Co., 1904), and was mentioned in Life

Magazine in 1905 (Volume 44, November 10, 1904, page 485), which also

printed a copy of one of the swap party cartoons.

Instructions for hosting a “swap

party” also appeared in Clara E. Laughlin’s, The Complete Hostess (New York, D. Appleton and Company, 1906, page

120).

Swap parties appear to have been

all the rage in 1906. But it is possible

that they may have been older. Although

the Table Talk article from 1901 lists “swap parties” among “novel entertainments,”

I found one earlier reference that hinted at, perhaps, an older pedigree. In an 1899 article about the Evacuation

Day celebrations among high-society types in New York City:

Swap parties appear to have been

all the rage in 1906. But it is possible

that they may have been older. Although

the Table Talk article from 1901 lists “swap parties” among “novel entertainments,”

I found one earlier reference that hinted at, perhaps, an older pedigree. In an 1899 article about the Evacuation

Day celebrations among high-society types in New York City:

The entertainment was of a festive order,

and continued until midnight. The

programme included a Revolutionary guessing bee, an old fashioned swapping

party, a “patriotic dance” by the little regent,[i]

recitations and music.

New York Tribune, November 27, 1899.

The reference to the “swapping

party” as “old fashioned” suggests that the “swap party” craze of the early

1900s may have been a revival of an earlier practice. The 1899 article, however, does not describe

what they meant by a “swapping party,” so it is impossible to judge whether it

was the same type of party that became popular after 1901.

A description of a “swap party”

at a sorority house in Ann Arbor suggests that swap parties were all the rage

at the University of Michigan in 1895. But

don’t get too excited, it’s not what you think (hope?); these swap parties were more in

the nature of an auction than . . . a wrapped gift exchange:

Eta. University

of Michigan.

Dear

Thetas: Are you all beginning to be

afflicted with “that tired feeling” which comes to us with the spring? It does not seem to be very seasonable with

us for we are still wading through snow-drifts.

However, everyone appears to be afflicted with the premonitory symptoms

and little is going on excepting an occasional “swap-party,” - - the momentary rage in Ann Arbor. It is a very jolly way to entertain one’s

friends, provided that the said friends have not taken part in too many similar

festivities. Each guest takes along some

ancient article of clothing or bric-a-brac for which he has no further

use. These are auctioned off, the

bidders offering what they have brought instead of money, and the owner of the

article under the hammer decides which is the highest bid. With a good auctioneer and funny things to be

auctioned, the bidding becomes very lively.

The Kappa Alpha Theta, Volume 9, Number 3, April, 1895, Burlington,

Vermont, 1895.

In any case, even if “swap

parties,” of any kind, were old-fashioned in 1899, they were not yet called “white elephant”

parties or “Yankee swaps;” those names would come later.

White Elephant Swaps/Parties

Even though the expressions,

“white elephant” and “gift of a white elephant,” seem, in retrospect, as

perfectly suited (if not obvious) to be the name of a “swap party,” the name did

not appear until 1907.

The earliest appearance of the

phrase is in a joke. The joke was

republished in dozens of outlets during its first year, and recurred from time

to time for more than a decade and into the 1920s. In modern parlance, we might say that the joke

went viral. The joke may, in fact, be

the origin of the phrase:

A shocking thing happened in one of our

nearby towns, says exchange. One of the

popular society women announced a “white elephant party.” Every guest was to

bring something she could not find any use for and yet too good to throw

away. The party would have been a great

success but for an unlooked for development which broke it up. Nine out of the eleven women invited brought

their husbands. – Primrose Record.

The Columbus Journal (Columbus, Nebraska), July 10, 1907.

This version, the earliest one I found, from Columbus, Nebraska, claims that the party was held in the nearby town of Primrose, Nebraska. But the joke was repeated dozens of times across the entire country. In each case, the location of the party changed, sometimes to a nearby town or neighboring state, and sometimes to a far-off big city.

This version, the earliest one I found, from Columbus, Nebraska, claims that the party was held in the nearby town of Primrose, Nebraska. But the joke was repeated dozens of times across the entire country. In each case, the location of the party changed, sometimes to a nearby town or neighboring state, and sometimes to a far-off big city.

The only reference to a “white

elephant party” from 1907, that was not merely a repetition of the “white

elephant” joke, is from the Madison (Wisconsin) High School’s 1907 yearbook, Ty-cho-ber-ahn. But even there, the reference is from a

mock-newspaper article with humorous stories about students in the school, not

an actual notice of a party to be held under the name, “white elephant

party.” So it is difficult to determine

whether the name preceded the joke, or whether the joke writer coined a new

expression. But in either case, the joke

seems likely to have spread new name, regardless of its origin. If the frequency of the joke in print is any

indication, it seems likely that anyone who had never heard of a “white

elephant party” before 1907 had heard of it by the end of 1908.

In 1908, the helpful-hints

columnist, Madame Merri, legitimized the expression, to the extent that it may

have needed legitimizing after its appearance in the joke. In her widely syndicated helpful hints

column, she provided detailed instructions for hosting a “White Elephant

Party,” including instructions for making special, elephant-shaped

invitations. The game instructions were

more or less identical to the “swap party” instructions that had been making

the rounds for years. To her credit, she

admits as much; “this has been tried before under the name of a ‘swap’ party.

Whatever it is called it makes a lot of merriment.” She also published the “White Elephant Party”

instructions in book form, in a collection of her articles published in 1913.

Madame Merri, The Art of Entertaining for

All Occasions; Novel Schemes for Old and Young at Home, Church, Club, and

School, Arranged by Months,

Chicago, F. G. Browne & Co., 1913, page 297.

Beginning in 1908, notices of

actual “white elephant” parties started to appear in newspapers. Those notices continued, with increasing

frequency, into the early 1910s, often in the society pages, and often hosted

by women’s groups or clubs. Such notices

were fairly frequent by 1913, the same year in which women’s clubs and

charitable organizations popularized the related expression, “white elephant

sale.”

White Elephant Sales

The earliest appearance of the

phrase, “White Elephant Sale,” is a commercial usage from 1892:

White Elephant

Sale.

An extraordinary opportunity to

get table linens cheap. Jos. Horne &

Co., 609-621 Penn avenue.

Pittsburg Dispatch (Pennsylvania), October 27, 1892, page 6.

Although this use of the phrase is an exact precursor of the phrase, it appears to have been a one-off, as the phrase did not take hold. This was the only example of the phrase that I could find before 1913.

Although this use of the phrase is an exact precursor of the phrase, it appears to have been a one-off, as the phrase did not take hold. This was the only example of the phrase that I could find before 1913.

The earliest use of “white

elephant sale” to describe a fund-raising rummage sale is from in 1913:

The Ladies’ Aid Society will hold a

“White Elephant” sale in the church parlors, Friday afternoon, March 14, 1913.

Perrysburg Journal (Perrysburg, Ohio), March 14, 1913.

|

| The Ogden Standard - 4/11/1918 |

Society women are keeping shop this week,

beginning Wednesday, when the American fund for French wounded, the

British-American war relief and the Red Cross helpers will be the beneficiaries

of their enterprise. . . . The white

elephant sale is a rummage sale, and those interested in the causes are begging

for discarded articles of any kind, especially books, jewelry, silver,

furniture and plants.

The Washington Herald (Washington DC), February 9, 1917, page 8;

White Elephant Sale.

The women of Lexington will hold a “White

Elephant” sale in the future for the benefit of the Armenian Fund, if

sufficient encouragement may be received in the way of contributions. One of the greatest tragedies of history and

the greatest of this war has been enacted in Armenia, and efforts of the

Central powers to eliminate the race by murder and starvation is without

parallel.

The Lexington Intelligencer, November 23, 1917, page 5.

“White elephant” gift exchanges

and “white elephant” sales were here to stay.

|

| Meade County (KS) News - 4/18/1918 |

Yankee Swaps

I do not know when the phrase

“Yankee swap” was first applied to “white elephant” gift exchanges, but it

appears to have been long after 1920. I

was unable to find any viable information on the subject. If you have any idea, I would be curious to

know.

The world awaits!

[i]

The “little regent” was Sarah Bancker Trafton, Regent of the Holland Dames, a

patriotic club of Old-New York Dutch families.

The Bancker

names is connected with New York City as early as the late 1600s; Anna

Bancker, the daughter of the Dutch sea captain, Gerrit Bancker, married

Johannes de Peyster, who was the mayor of New York in 1698. Several of her female descendants married

cousins with the name Bancker – so her marriage did not end the association of

the name Bancker with New York City.