Widely circulated rumors suggest that

white Americans once used black Americans as bait for hunting alligators. The perception that such rumors may be true

has been bolstered in recent years by otherwise respected sources treating the rumors

seriously.[i]

The stories may make excellent

Crocodiles abound in Ceylon, and in many places the natives will “salaam” in dread to the water. At Galle, in the southern province, a saurian was lately killed, whose stomach was found to contain two human skulls. The crocodiles are very wary, and difficult to kill, and generally manage to sink themselves out of sight.

Our sketches are by Major-General H. G. Robley, who writes: – “My first represents the trail of a big saurian being discovered on a water-side bank. No. 2 refers to the arrangements at a neighboring village for bait, so as to get a sure shot. It is tedious work waiting for the man-eater to come out of the water, but a fat native child as a lure will make the monster speedily walk out of the aqueous lair. Contracting for the loan of a chubby infant, however, is a matter of some negotiation, and it is perhaps not to be wondered at the mammas occasionally object to their offspring being pegged down as food for a great crocodile; but there are always some parents to be found whose confidence in the skill of the British sportsman is unlimited. No. 3 gives a view of the collapse of the man-eater, who, after viewing the tempting morsel tethered carefully to a bamboo near the water’s edge, makes a rush through the sedges. The sportsman, hidden behind a bed of reeds, then fires, the bullet penetrates the heart, and the monster is dead in a moment. The little bait, whose only alarm has been caused by the report of the rifle, is now taken home by its doting mother for its matutinal banana. The natives wait to get the musky flesh of the animal, and the sportsman secures the scaly skin and the massive head of porous bone as a trophy.”

The Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kansas), September 29, 1899, page 11 (See, "Did Crocodile Hunters Use Babies as Bait in India?," Janaki Lenin, September 8, 2016).

Sometimes, however, “alligator bait” was sometimes just that – alligator bait. In the first cartoon, when a goat swallows a rope attached to alligator bait, the goat inadvertently becomes the bait. In the second, two white guys are served up as alligator bait.

And even when the notion of "alligator bait" (if not those words, specifically) was used figuratively, the "bait" was not always black. Here, a white boy is dangled as bait in a political poster opposing votes in favor of the sale of liquor.

Some advertising images appear to have borrowed from the earlier crocodile hunting stories out of Ceylon - at least in mirror image.

McCrary & Branson's “Alligator Bait” and the copycat images and other items that followed were not the first such images. Earlier images played off the notion of alligator preference even before the idiomatic use of “alligator bait” came into wide usage.

Taking the Bait

There is at least one example of a black child nearly "eaten" in front of a white man for sheer amusement; but only the child was amused -- it was a practical joke and a white man took the bait, hook-line-and-sinker.

“click bait,” but the sources cited do not generally prove the historical truth of supposed, human

“alligator bait.”

“alligator bait.”

The case in favor of a factual basis

of the rumor is generally staked on a few isolated “facts” cherry-picked from two

isolated “news” items; a 1923 article about alligator hunting in Chipley,

Florida, and an account of moving alligators from the winter quarters to their

summer quarters at the Bronx Zoo in 1908.

Taken at face value and in their entirety, however, those articles do

not actually say what the proponents suggest they do, and in any case, it’s not

clear how seriously those articles were taken when they were published, and

there are several good reasons to doubt the factual basis of both stories.

Other evidence cited in support of

the factual basis of the rumor include souvenir postcards, knick-knacks and

other novelty items showing alligators threatening or eating black children,

many of them labeled with the expression “Alligator Bait.” But those items may simply be “jokes,” cruel

jokes in keeping with the casually racist attitudes and language of the day; puns

on the then-current expression, “alligator bait,” an idiom for black

children. The idiom first came into

widespread use in the wake of publication of a wildly successful, mass-marketed

photographic print entitled “Alligator Bait,” produced by McCrary & Branson

Studios of Knoxville, Tennessee, not as the result of sudden, widespread

awareness of dangerous and cruel hunting practices.

“Alligator Bait,” McCrary &

Branson, Knoxville, Tennessee, 1897.

The idiom itself is not evidence of

such hunting practices, but more likely an echo of the old wives’ tale that

alligators (and crocodiles before them) preferred small children over adults,

and black children over white children.

They have a weakness for pigs and puppies, and special

fondness, it is said, for pickaninnies – negro children; but the instances in

which they have been the aggressors in attacks on grown people are rare . . . .

Detroit Free Press, September 15, 1895, page 27.

Similar superstitions about

crocodiles date back to at least as early as the late-1700s. In Egypt, they were said to prefer Muslims

over Christians, and along the west coast of equatorial Africa, they

purportedly preferred “negroes” over Christians.

The Best “Evidence”

Alligator hunters in Chipley,

Florida, they say, used black children as bait.

But what’s conveniently left out of most accounts is the fact that their

mothers willingly rented out their own children for $2 a day, the babies came

out of the water “wet and laughing,” and there was no real danger because the

hunters “do not ever miss their targets.” Perhaps even more damning than such

questionable “facts” is the story’s close similarity to a decades-old string of

dubious “crocodile bait” stories, purportedly out of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka),

East India, India or the Sudan, the first of which was written by a

military-humor cartoonist in 1888. And finally,

the Chipley version of the story was written by an itinerant newspaper

telegraph operator and copy reader a colleague accused of “hooey,” and who

later prospered in a second career as a “sex philosopher” and lecturer with

live demonstration models.

The Bronx zoo story that suggested

two black children were used as “bait” to lure alligators into their summer

pool does not square with a more factual description of the same events

published simultaneously the same day. The

New York Times reported simply that

the “alligators came out willingly into the cage after a prod from the long

sticks.” But even if the more sensational

version is presumed true, the children are said to have “darted around the

tank,” which is consistent with running around the outside perimeter of the

enclosure. And the alligators are said

to have fallen “with grunts of chagrin into the water, disappointed of their

prey,” so it is unclear whether the children, assuming they were there, were

ever in harm’s way.

The case for the truth of the rumors

is also supported by souvenir postcards and novelty items showing alligators

threatening black children, frequently titled or labeled as “Alligator Bait,”

and numerous references to “alligator bait,” once a common idiom meaning “black

children.” But the postcards and novelty

items may simply be visual puns playing off the idiom; jokes, tasteless to be

sure, but not evidence of dangerous or cruel alligator hunting practices. The postcards and novelty items appeared

after 1898, the year in which the expression “alligator bait” first became

widely known and used. The expression

came into widespread use following release of a wildly successful,

mass-marketed photographic image of a group of black babies entitled “Alligator

Bait,” not due to any sudden or growing awareness of any actual alligator

baiting.

Although the expression “alligator

bait” may conjure up images of dangerous hunting practices, there is no evidence

that it was derived from any such practices.

Early, pre-1898 examples of the expression suggest it was used among

black children themselves, as a playful taunt.

In an article about an African-American boy describing his efforts to

capture an escaped pet alligator in Kansas, he was described as having nearly

become “alligator’s bait.” It was also

used as an insult for a couple white, Southern politicians, and as a

description of a group of white boys taking a raft into alligator infested

waters.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the earliest example of the expression was in a punch line of a widely circulated joke in 1883, about white, pasty, anglophiles – referred to by the recently coined term, “Dudes.”

Surprisingly, perhaps, the earliest example of the expression was in a punch line of a widely circulated joke in 1883, about white, pasty, anglophiles – referred to by the recently coined term, “Dudes.”

“I suppose you have heard of our dudes, Miss Clarwa?”

observed a New York swell to a Jacksonville girl.

“Oh, yes,” she answered, “they are becoming very popular in

Florida. We use them for alligator

bait.”

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 15, 1883, page 4.

And in the earliest story in which American babies were said to be used as alligator bait, “a nice, fat baby is rented for the occasion from the cracker [(poor, southern white)] mother to whom a half dollar is ample recompense for the risk that her child is to run.” The Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kansas), September 29, 1899, page 11.

And in the earliest story in which American babies were said to be used as alligator bait, “a nice, fat baby is rented for the occasion from the cracker [(poor, southern white)] mother to whom a half dollar is ample recompense for the risk that her child is to run.” The Topeka State Journal (Topeka, Kansas), September 29, 1899, page 11.

The origin of the idiom “alligator

bait,” referring to black children (and frequently applied to adults as well),

may have its roots in a centuries old superstition, first recorded in the

1700s, that crocodiles (and later alligators, by extension) were discriminating

diners, preferring the taste of Muslims or “negroes” over Christians. The earliest reports of such beliefs came out

of Egypt and “Western Ethiopia,” which under the nomenclature of the time

likely referred to the west coast of Africa, in the region of Cameroon.[ii] So it is possible that the folk tale could

have been transferred to the New World as part of the oral tradition of

enslaved people brought over from the west coast of Africa, or through

references to them in English language texts published in England and the

United States, or both.

Although references to the myth have

persisted for centuries, it’s not clear how many people ever took it

seriously. For example, an enslaved man

on a Georgia plantation gave the following advice on how to avoid the

bloodhounds to a Union soldier recently escaped from Rebel custody.

He assured us that the dogs were fearful of the alligators

with which that river abounded, and that the slaves were taught that alligators

would destroy only negroes and dogs. He

didn’t believe it himself, although his master thought he did.

Captain J. J. Geer, Beyond the lines: or a Yankee Prisoner Loose

in Dixie, Philadelphia, J. W. Daughaday, 1863, page 128.

While tales of using black children

may seem plausible in light of the well-documented history of slavery, Jim Crow

laws and extra-legal mob action like lynching, the specific allegations of

placing children in harm’s way as “alligator bait” are not well

substantiated. Before drawing any

conclusions about the underlying factual basis of sensational rumors, one

should make a comprehensive survey of a wide spectrum of relevant sources and

references from the period, not simply cherry-pick a few purported “facts” from

questionable sources.

You be the judge. But don’t jump to conclusions.

Chipley, Florida, 1923

The most frequently cited piece of

“evidence” in support of the truth of the rumors is a 1923 article about

children used as live alligator bait in Chipley, Florida. But if that article is to be taken seriously

on its face, the children’s parents are at least as culpable as the hunters,

renting their own children to strangers for $2.00 a day. And besides, if, as the article suggests in a

detail conveniently omitted from most discussions of the practice, the babies

“go into the water alive and whole and come out wet and laughing” because

“Florida alligator hunters do not ever miss their targets,” the whole thing

wasn’t as dangerous as one might suppose.

But that, of course, would be ludicrous.

Mobile, Ala., Sept. 14. – Naked pickaninnies are being used

as alligator bait around Chipley, Florida!

But wait. These little black morsels are more than glad to be

led to the “sacrifice,” and do their part in lurking the big Florida ‘gators to

their fate without suffering so much as a scratch.

With the demand for tanned alligator hides far outstripping

the supply, hunters along the Santa Rosa coast of Florida have beset themselves

to helping relieve the shortage and incidentally to fatten their purses. And little negro babies are providing a

necessary part of the ‘gator hunters’ equipment.

No, the pickaninnies are not torn cruelly asunder, like

wiggling worms, and placed bit by bit upon giant fishhooks, but go into the

water alive and whole and come out wet and laughing.

Aside from the novelty of the method, this baiting alligators

with negro babies, a scheme said to have been originated by a Chicago man,

there is nothing so terrible about it, except that it is spelling death for the

alligators.

Above all other things, the alligator is most fond of human

flesh as an item of diet. Hunters say

that while an alligator will risk its safety for young dog, it will jeopardize

every hope of life for a live baby. And

in the matter of color, the additional information is vouchsafed that black

babies, in the estimation of the alligators, are far more refreshing, as it

were, than white ones.

According to reports, the method of baiting with the negro

baby is simplicity Itself. Nothing is needed but the pickaninny and a

Winchester rifle or two. The baby is placed in the edge of the water where it

is shallow, near the alligator's haunts, and the rifle in the hands of expert

shots, who are hidden behind nearby clumps of bushes and dense growths of marsh

grass.

The “bait” is placed in water Just deep enough so that it can

frolic and play and splash its fingers through the water and white sand in

childish glee. The “bait” is used naked,

which adds no little, so the hunters are said to have discovered, to the value

of the “lure.” A black baby, or a baby of any other color, it is well known,

likes to splash in the water when clothed, but stripped naked the child is in a

heaven of delight and makes a great to do, chortling and laughing, which

attracts the 'gator.

Hunters declare that before the “bait” has emitted half a

dozen giggles or laughs, or coos, as his humor may prompt, a slight rustling is

heard in some nearby lagoon, and presently a long, dark, shadowy line is

detected beneath the water, creeping toward the poor little "bait."

Now, the baby is always placed in such a position that there

is shallow water for a considerable distance beyond him, out into the water.

Then as the 'gator draws near he is forced above the surface, wading toward the

“bait” with his head and forequarters well ex-posed. Then –

Bing, bing, bing! Three or four rifle shots ring out, and the

hunters rush into the water to retrieve their prize. For Florida alligator hunters do not ever

miss their targets.

And as they rush, also rushes, usually, the mother of the

“bait,” who almost always accompanies her “coal black rose” to the hunting

place. As the mother gathers up her

offspring the hunters finish off the ‘gator by blows from heavy clubs.

And usually while one of the hunters drags the “game” well up

on the sands another of the group pays off the mother for the use of her negro

baby. There Is a set price. It is:

Two dollars.

Akron Beacon Journal, September 14, 1923, page 4.

Some people took the reports

seriously at the time. The NAACP, for

example, put out a press release about the Chipley story; a shortened version

of the story appeared in several African-American newspapers. Tellingly, perhaps, their account reported on

the supposed events in Chipley, without reference to any historical context of

similar, known hunting practices. In 1923,

the people who worked at the NAACP or wrote and edited African-American

newspapers would have had parents or grandparents who had lived under slavery,

or parents, grandparents, friends or other relations who had lived in the deep

south before migrating north, who would have been familiar with similar events,

assuming they had happened with any frequency, and yet the reports of the

NAACP’s response and accounts of the purported incident in Chipley, Florida made

no allusion to any similar hunting methods ever having been used regularly, or

at all.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, 69 Fifth avenue, New York City, today made public the contents of a

dispatch printed in the Louisville, Kentucky, Herald, of Sept. 23rd, stating that Colored babies were

being used as alligator bait in the vicinity of Chipley, Florida.

The Colored babies are allowed to play in shallow water, with

expert riflemen concealed nearby. When

the alligator approaches his prey he is said to be shot by the riflemen. The dispatch states that “Florida alligator

hunters do not ever miss their targets.”

The price reported as being paid Colored mothers for the use of their

babies as alligator bait, is said to be two dollars

The Buffalo American (Buffalo, New York), October 11, 1923, page 1.

Even Time magazine reported the fact of the article, but without

vouching for its veracity. They

published a rebuttal several weeks later.

On behalf of the town of Chipley, Fla., the Orange County

Chamber of Commerce branded as “a silly lie, false and absurd,” the story

(broadcasted a month ago through the press of the nation) that colored babies

were being used at Chipley for alligator bait. In its issue for Oct. 15, TIME

printed the fact that the report had been circulated, but in no wise vouched

for its authenticity. TIMES story was as follows: From Chipley, Fla., it was

reported that colored babies were being used for alligator bait. “The infants

are allowed to play in shallow water while expert riflemen watch from concealment

nearby. When a saurian approaches his prey, he is shot by the riflemen.”

The Louisville Herald: “Florida alligator hunters do not ever

miss their target”

The price reported as being paid colored mothers for the

services of their babies as bait was “$2.00 a hunt.”

“Were Children Used as Alligator Bait

in the American South?” David Emery, Snopes.com, June 9, 2017.

But not everyone took the story

seriously.

Just a Liar – Macon Telegraph: It takes all sorts of folks to

make up the world, including the blockhead who believes that negro babies are

used as alligator bait in Florida.

The Tampa Tribune, November 2, 1923, page 4.

Similarly, when a

white grocer from Louisiana named Garland Rue told a reporter in 1988 that his

great-uncle had used his father as alligator bait, the reporter expressed

skepticism.

Now Garland is one Crowley old-timer

whose memories I trust. However, he told

one tale that I’m a bit dubious about:

“My father was raised in Cameron

Parish,” he said. “His parents died when

he was very young, and his uncle put him out on the bank for alligator bait,

then would shoot the alligators.”

The Crowley Post-Signal (Crowley, Louisiana), September 13, 1988, page 2.

The original “crocodile bait” story

from Ceylon in 1888 had a similar effect on a reader in New Zealand who claimed

to have spent a lot of time in that country.

All I can say in reference to this is that, though I have

been a great deal in Ceylon, I never saw the parents who would have hired out

their children for such diabolical purposes – one good reason being that in

many cases the alligator comes along so quickly that no hunter, however sure a

shot, could be certain of saving a child bound to a stake under such

conditions.

Otago Witness

(Otago, New Zealand), July 6, 1888.

And even assuming parents actually

did rent out their children as crocodile bait in India, it was reportedly

difficult to rent similar alligator bait in Florida.

I was in Florida a year or so ago, and tried to hire a baby

to experiment with for alligators after the method in India, but folks who

owned babies down there didn’t seem to enter into the spirit of the sport, and

I couldn’t get one. I compromised on a

rather lively complaining dog. He was a

success, and I had quite a lot of fun, although the sport was a good deal tamer

than it would have been if I had only had a baby for bait.

New York Sun, June 24, 1894, page 24.

These earlier skeptics do not

necessarily disprove the stories, but they should give pause to modern readers

eager to believe them as fact based on the thinnest of evidence. If so many contemporary readers did not take

them seriously, perhaps they should be taken with a grain of salt today.

And there may be good reason to take

the story with a grain of salt. The

Chipley, Florida story was written by an itinerant telegraph operator and

newspaper copy reader who later found more success as a self-styled “professor”

and “sex philosopher,” giving sex-education lectures with “live models” to demonstrate

the action, in what was seems to have been a thinly-veiled soft-core strip

tease act. He also hosted radio call-in

shows with a psychic, answering questions about sex and relationships. A former newspaper colleague accused him of

“hooey,” and his models’ brassieres and panties were once confiscated and sold

at auction to satisfy a bad debt.

T. W. Villiers

Thomas Wayland Villiers was born in

Ohio in about 1890, the son of “an illustrious sexologist” and “nephew of

America’s highest salaried Baptist minister.”[iii] At the time of the 1940 census, he lived in

Franklin, Ohio with his wife Alice (25 yrs), and reported his occupation as

“lecturer/salesman” in the “retail” industry.

Years earlier, however, he worked as a telegraph receiving operator for

a newspaper in West Virginia, where he also served as timekeeper for local

boxing matches.[iv]

In 1920, his article, “Trials of a

Receiving Operator,” appeared in an Associated Press service bulletin.

During the year before publication of

his “alligator bait” piece, his name appears in three other articles, all

published as dateline Mobile, Alabama, the same location as the dateline on his

Chipley, Florida piece. In the first of

those articles, he is named as the author of an open letter to the WDAE radio

station in Tampa, Florida. He identified

himself as the “Radio Editor” of the “Register,” presumably the Mobile Register.

Mobile, Ala., Nov. 3. WDAE: Picked up your concert here on

one tube. Cut in with one stage

amplifier and couldn’t keep the phones on my ‘bean.’ T. W. Villiers, Radio

Editor, Register.

Tampa Times,

November 8, 1922, page 8.

Six months later, he penned a

far-fetched article about a textbook supposedly banned by pro-prohibitionists

because of a scientific illustration characterized as a “still.”

Apparently determined to do its part in helping the youth of

Alabama forget there ever was such a thing as whiskey or other “hard”

drinkables in common use in America, the Alabama State Text Book Commission has

ordered discarded a grammar school text book, in use in all of the schools of

the state. It contains a picture of a

still. . . .

The miniature distilling apparatus was used to illustrate the

principle of converting liquids into steam and from steam back to liquids.”

Shreveport Journal (Shreveport, Louisiana), May 15, 1923, page 5.

In early September, less than two

weeks before his “alligator bait” story hit the presses, he was named as a

local dog fancier whose German Shepard, “Rino Von Zavelstein,” performed

wonders on the golf course.

Many stories have been told tending to prove the

extraordinary intelligence of the German shepherd police dog, but T. W.

Villiers, Mobile fancier, has re-named his imported police dog “Golf Hound,”

and incidentally has quit paying caddies to search for golf balls. Rino Von Zavelstein, the canine caddy calmly

stands behind his master until he swings, Villiers says, then dashes off after

the ball. He does not pick it up but

stands over the ball as a living “marker” until the player comes up for the

next shot.

Knoxville News-Sentinel, September 3, 1923, page 3.

Following his “alligator bait” piece,

however, T. W. Villiers disappears from the headlines, at least as a

writer. Years later, he would reappear

as the subject of news articles and in advertisements for his new career as a

sex lecturer.

|

Knoxville Journal, March 23, 1932, page 8.

|

From as early as 1928, and continuing

through at least 1935, “Professor Wayland Villiers” gave sex lectures in

conjunction with “educational” films, sometimes with one or several “live

models” onstage to give demonstrations.

|

The Danville Bee (Virginia), March 18, 1933, page 10.

|

Advertised as, “clean,” “moral,” and

“legal,” the performances seem to have been (like his models) thinly veiled

excuses for soft-core nudity.

During a run in New York City, famed,

syndicated gossip columnist Walter Winchell recognized him from his newspaper

days.

Prof. Wayland Villiers who lectures on sex at the 42nd

street stand is the same chap who headed the “copy desk” of the old St. Louis Globe a few yrs back.

“On Broadway,” Walter Winchell, Nevada State Journal (Reno, Nevada),

June 7, 1932.

A former colleague also recognized

him in Knoxville, Tennessee, and outed him as just an old “copy reader,” while praising

him for his newfound business savvy and divulging his personal problems.

You’ve gone a long ways, Tom, since you and I used to sit

side by side at the Press-Scimitar

news desk in Memphis four years ago and write headlines. Your mustache wasn’t waxed then and if

anybody called you “Professor” Villiers you would have haw-hawed him a handful.

. . . You had ‘em leaning forward in their seats when you

told them you’d reveal how they could tell a girl is chilly. I still don’t know how to tell from what you

said last night, tho.

And then the way they ate up those books you sold at $1 for

two. You brought the hoarded dollars,

Tom. You ought to be working for Col.

Frank Knox. . . .

So you got your degree of doctor at the Institute of

Bio-Psychology, New York. I don’t find

it listed in the World Almanac but I suppose it’s all right. . . .

I had a telegram from Jim Joyce, managing editor of the Press-Scimitar, about you

yesterday. Jim says that when you worked

for him you were “bothered continually by affairs of the heart and

pocketbook.” That’s what your name meant

in Memphis. But don’t pay any attention

to Jim. He doesn’t realize like I do now

that you were an artist at heart, Tom, and those little things ought to be

overlooked. . . . “Professor” Steve Humphrey, Authority on ex-copy readers,

sexologists and hooey.

Knoxville News-Sentinel, March 22, 1932, page 1.

Villiers also took his show on the

radio, sometimes hosting call-in shows where he answered sex and relationship

questions while his co-host, a Danish psychic billed as Princess Signe Serene,

addressed listeners’ spiritual questions.

|

| https://tenwatts.blogspot.com/2014/07/wayland-villiers-radio.html |

Not that someone who gives

light-hearted lectures about sex might not have also done serious work on some

other subject, but in light of all of the circumstances, the arc of his career,

other writings, the factual basis of Villiers’ frequently-cited 1923 story

should at least be called into question.

The story should also be questioned because of its striking resemblance

to a decades-long string of “crocodile bait” stories, all apparently derived

from an 1888 original pen by a military-humor cartoonist named Major-General

Robley,

Crocodile Bait

Villiers’ 1923 “alligator bait” story

appears to be a retread of a decades-long string of “crocodile bait” hoaxes

dating back to 1888, each one borrowing from the last with increasingly far-fetched

embellishments. Within a few months of

the publication of the original story in the British magazine, The Graphic, in late-January 1888,

several variants appeared in hundreds of newspapers and magazines throughout

the United States, Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand. No fewer than nine distinct versions of the

original story appeared in hundreds more newspapers on a regular basis for more

than three decades.

The original “crocodile bait” story

of 1888 claimed that British hunters in Ceylon rented small children from

locals to use as crocodile bait. While

not every parent was willing to risk their children’s lives, British crocodile

hunters’ sharpshooting skills were apparently as highly regarded as those of alligator

hunters in Chipley thirty-five years later; they could always find parents whose

“confidence in the skill of the British sportsman is unlimited.” And like the children in Chipley, Florida, no

harm ever came to the children of Ceylon. Following the kill-shot, “[t]he little bait,

whose only alarm has been caused by the report of the rifle, is now taken home

by its doting mother for its matutinal banana.”

Robley’s story, which first appeared

in The Graphic (London), included

nearly all of the basic elements of its later variants.

Sport in

Ceylon — shooting a man-eating crocodile

Crocodiles abound in Ceylon, and in many places the natives will “salaam” in dread to the water. At Galle, in the southern province, a saurian was lately killed, whose stomach was found to contain two human skulls. The crocodiles are very wary, and difficult to kill, and generally manage to sink themselves out of sight.

Our sketches are by Major-General H. G. Robley, who writes: – “My first represents the trail of a big saurian being discovered on a water-side bank. No. 2 refers to the arrangements at a neighboring village for bait, so as to get a sure shot. It is tedious work waiting for the man-eater to come out of the water, but a fat native child as a lure will make the monster speedily walk out of the aqueous lair. Contracting for the loan of a chubby infant, however, is a matter of some negotiation, and it is perhaps not to be wondered at the mammas occasionally object to their offspring being pegged down as food for a great crocodile; but there are always some parents to be found whose confidence in the skill of the British sportsman is unlimited. No. 3 gives a view of the collapse of the man-eater, who, after viewing the tempting morsel tethered carefully to a bamboo near the water’s edge, makes a rush through the sedges. The sportsman, hidden behind a bed of reeds, then fires, the bullet penetrates the heart, and the monster is dead in a moment. The little bait, whose only alarm has been caused by the report of the rifle, is now taken home by its doting mother for its matutinal banana. The natives wait to get the musky flesh of the animal, and the sportsman secures the scaly skin and the massive head of porous bone as a trophy.”

The Graphic

(London, England), January 21, 1888, page 54 (text) and 73 (images).

H. G. Robley

|

| Thomas Maclauchlan, History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments, Edinburgh, T. C. Jack, 1887, frontispiece. |

Major-General Horatio Gordon Robley

spent the final seven years of his career in Ceylon, where he would have had

the opportunity to observe local crocodile hunting practices. But he was also known as a contributor of

military-humor cartoons to the British humor magazine, Punch, which raises the question of whether his contribution to The Graphic was serious reportage, or

another example of military humor of the sort he submitted to Punch.[v]

In one of his cartoons, a

peace-loving “Ferris Bueller” plays hooky.

Captain of Rural Corps (calling over the Roll). “George

Hodge!” (No answer.) “George Hodge! – Where on Earth’s George Hodge?”

Voice from the Ranks. “Please, Sir, he’s turned dissenter,

and says fighting’s wicked.

Punch, Volume

64, April 12, 1873, page 156 (the script ‘R’ in the corner signifies Robley[vi]).

In another, an officer volunteers to

be taken prisoner to avoid risking his life in a fight.

DIVISION OF

LABOUR.

Facetious Volunteer Sub. “Look here, Captain; I’m tired of

this fun. Do you mind looking after the

men while I go and get taken prisoner?”

Punch, Volume

66, May 16, 1874, page 210.

In a similar vein, the “British

sportsman” in Robley’s contribution to The

Graphic hides “behind a bed of reeds” with a rifle while an unarmed “chubby

infant” sits out in the open near crocodile-infested waters because its

parents’ “confidence in the skill of the British sportsman is unlimited.”

Serious, or hilarious?

Harper’s Bazar

Whether serious or not, Robley’s

story spawned a string of imitators, each one embellishing the story with even

more sensational details, many of them using the same images or poor reproductions.

Two weeks after its initial

appearance in The Graphic, a nearly

identical story appeared in Harper’s Bazar, a weekly magazine with a large,

national distribution in the United States.

The Harper’s article used all three of the images from The Graphic, one of them cropped to fit

in a different arrangement. The

accompanying text borrowed heavily from Robley’s original, while adding a few

more dramatic elements. For example, Harper’s expanded Robley’s description

of the “chubby infants” into “chubby, rice-distended, squally infants.” Harper’s

also dramatized the death of the crocodile, which Robley simply described as, “The

sportsman, hidden behind a bed of reeds, then fires, the bullet penetrates the

heart, and the monster is dead in a moment.”

As the bullet penetrates the heart this enormous rudder flaps

convulsively, the pale fishy eyes are covered with the film of death, the

tongueless cavern of a mouth (the gullet of which is closed with a valve) shuts

with pistol-like snap, the two front lower-jaw tooth (which are longer than the

rest) now show their points through corresponding holes in the snout. (This

makes the difference between the crocodile and the alligator).

Harper’s

Bazar, Volume 21, Number 5, February

4, 1888, page 76.[vii]

Harper’s omitted

the detail about the parents’ “unlimited” confidence in the British sportsman;

it was, after all, an American magazine.

American Newspapers

Less than a week after Harper’s carried its version, yet

another knock-off appeared, introducing what would become recurring themes in

later versions, that the crocodile is “lazy,” suffers from “ennui,” but can be

roused immediately when tempted by a “dark brown infant.” This version begins with an introduction that

pokes fun at the proliferation of American classified advertisements for

anything under the sun, with colorful musings about what a classified ad for

Ceylonese babies might look – “if newspapers abounded in Ceylon as much as

crocodiles do,” but since newspapers didn’t abound in Ceylon, hunters were

limited to “personal solicitation,” a phrase that in one form or another

appears in numerous, later versions of the story.

If newspapers abounded in Ceylon as much as crocodiles do,

advertisements worded like the foregoing would be common in their want

columns. As it is, the English crocodile

hunter has to secure his baby by personal solicitation. He is often successful for Ceylon parents, as

a rule, have unbounded confidence in the hunters, and will rent their babies

out to e used as crocodile bait for a small consideration.

Ceylon crocodiles suffer greatly from ennui. They prefer to lie quite still, soothed by

the sun’s glittering rays, and while away their lazy lives in meditation. But when a dark brown infant with curling

toes sits on a bank and blinks its eyes at them, they throw off their cloak of

laziness and make their preparations for a delicate morsel of Ceylonese baby

humanity. When the crocodile gets about

half way up the bank the hunter, concealed behind some reeds, opens up fire,

and the hungry crocodile has his appetite and life taken away at the same

time. The sportsman secures the skin and

head of the crocodile, and the rest of the carcass the natives make use of.

The Owensboro Messenger (Owensboro, Kentucky), February 10, 1888, page 3.

This version would ultimately appear

in hundreds of newspapers throughout the United States, Britain, Australia and

New Zealand. The story would later

boomerang back to the United States, with slight variations.

“Decoy” - The Golden Argosy

Two months after Robley’s original

appeared in The Graphic, a second

popular American magazine with national distribution published a short story

apparently based on the original.

Captain Henry F. Harrison’s story, “Decoy,” appeared in the March 24,

1888 issue of The Golden Argosy, an

adventure magazine targeting young boys.

Henry F. Harrison was a frequent

contributor to The Golden Argosy, but

does not seem to have published anything under that name elsewhere; perhaps it

was a pseudonym. At the time, a story

under his name appeared in nearly every issue of the magazine. He claimed to come from a family of sailors

going back two hundred years. Some of

his stories were styled as his father’s stories, some as his

grandfather’s.

“Decoy,” Captain Henry F. Harrison, The Golden

Argosy, Volume 6, Number 17 (Whole Number 277), March 24, 1888, page 268.

“Decoy” was written in first-person,

as though it actually happened to him. “Decoy” was accompanied by the original image

from The Graphic showing the

crocodile being shot. The Golden Argosy used a second one of

Robley’s images (the hunter bargaining with parents) a few weeks later, in

another story by Harrison, but in a completely different context and meaning.[viii]

“Two Queer Adventures,” Captain Henry

F. Harrison, Golden Argosy, Volume 6,

Number 20 (Whole Number 280), page 316. Caption – In Another Moment the Entire

Family Came Out to Meet Me.

Harrison’s story, “Decoy,” differs

from most of the crocodile hunting stories in that the baby-baiting crocodile

hunting technique is practiced by the locals, not by a British colonial. The American protagonist is in East India

hoping to observe a native crocodile hunt.

On his way to the hunt, he sees a toddler tied to a stake near the

river. He sees a crocodile approaching

the child and shoots it to save the child.

He is then set-upon by a number of locals, angry that he had disturbed

their hunt. They had hoped to take the

crocodile alive, and had used the baby to attract the crocodile.

The Captain, angry that locals had

endangered the child, takes it back to the village hoping to reunite it with

its parents, but without luck. “No one

pretended to know anything about it. The

brute had probably bought the baby for a few rupees of some of the very poorest

and most degraded of the natives, and they of course would not let themselves

be known. The man whom I employed as an

interpreter told me very cooly that I mustn’t think anything of such little

affairs – they were common enough in this part of India.”

The American, disgusted with the low

value the locals placed on human life, takes the child into his own custody,

raising him as his own – well, not exactly as his own, but as his ward living

as a close member of his family circle.

He names the boy, “Decoy.” Years

later, when they are back in India, the local hunter whose hunt the American

had ruined years earlier recognizes him and attacks him; his ward, Decoy,

reacts and saves his guardians life, repaying the favor of many years before. It’s all very neat and tidy, and coming so

soon after the basic crocodile-hunting appeared, seems more like a

fictionalized version of the original than fact.

New Zealand

When newspapers in New Zealand picked

up the American newspaper version nearly verbatim, they added the detail that

the story had appeared in the Ceylon

Catholic Messenger. But once again,

the story, at least as it is said to have appeared in Ceylon, did not suggest

that such classified ads actually did exist in Ceylon, it merely imagined what

they would like if they were to exist.

It is not clear whether the American

article had actually appeared in the Ceylon

Catholic Messenger or not, but the authors of an academic paper with a

survey of news accounts of crocodile hunting in Ceylon (including a Sri

Lanka-based herpetologist)[ix]

failed to find the story.

The New Zealand version found its way

back to the United States, where it appeared in dozens of newspapers. The reference to its purported appearance in

a Ceylon publication may have served to lend the new version a gloss of

legitimacy.

Compare:

If mothers in general shared the nerve exhibited by mothers

in Ceylon, trouble would be spared in many a household: “Babies wanted for

crocodile bait. Will be returned

alive.” If newspapers abounded in Ceylon

as much as crocodiles do, (says the “Ceylon Catholic Messenger”),

advertisements worded like the foregoing would be common in their want

columns. As it is, the English crocodile

hunter has to secure his baby by personal solicitation.

Ashburton Guardian (Ashburton, New Zealand), September 14, 1889, page 2.

If mothers in general shared the nerve exhibited by mothers

in Ceylon, trouble would be spared in many a household: “Babies wanted for

crocodile bait. Will be returned alive,”

says the New Zealand Tablet. If newspapers abounded in Ceylon as much as

crocodiles do, says the Ceylon Catholic

Messenger, advertisements worded like the foregoing would be common in

their want columns. As it is, the

English crocodile hunter has to secure his baby by personal solicitation.

Omaha Bee

(Omaha, Nebraska), March 9, 1890, page 23.

Kinghorn

The imagined classified ad versions

of the story seem to have inspired another writer to take it one step further,

and claiming that he had actually seen such advertisements in Ceylon. The narrator, Richard Kinghorn, described his

own crocodile hunts in India with the familiar language of “lazy” crocodiles

suffering from “ennui.”

“When I first saw this advertisement in a Ceylon newspaper,”

said Richard Kinghorn, a guest at the Richelieu, “I thought it was a joke. Afterwards I learned that it was by this

means that the crocodile hunters secured their bait. It is no trouble for an English crocodile

hunter to get these little children. The

Ceylon parents have full confidence in Englishmen, and they will rent out their

babies to be used for crocodile bait for a small sum.

“The Ceylon crocodiles are lazier than any other and are

harder to get. They lie for hours

perfectly motionless, basking in the sun.

Hardly anything can stir them.

But when tempted by a fat Ceylon baby placed on the banks of the stream

they shake off their ennui and their mouths water for a delicate morsel of

brown baby. The crocodile gathers

himself together and starts out for the infant.

When he gets about half way up the bank the hunter, concealed behind

some reeds, opens fire and gets his game. Then the baby is taken home to its loving

parents, to be used for the same purpose the next day. The sportsman secures the skin and the head

of the crocodile and the natives are given the rest of the carcass.

I’ve shot everything from the little prairie dogs to grizzly

bears, but for excitement crocodile shooting with babies for bait is out of

sight.”

Chicago Tribune,

May 28, 1890, page 8; The Weekly

Iberville South (Plaquemine, Louisiana), April 27, 1895, page 4.

It’s not clear whether Richard

Kinghorn was an actual person or not. A

prominent businessman and sportsman from Quebec named Richard Scobell Kinghorn

died in Montreal at the age of 62[x],

but there is no explicit connection between the two, aside from the coincidence

of the name. It’s possible, just

possible, that the name is as phony as the story.

Kinghorn’s version appeared in dozens

of newspapers in the United States in 1890.

When the same version popped up a few years later in alligator country,

Plaquemine, Louisiana, the paper (significantly perhaps) made no mention of any

similarity to alligator hunting practices in the American South.

Atkinson

On May 27, 1891, almost a year to the

day after Kinghorn reportedly told his croc story at the Richelieu Hotel in

Chicago, an “English traveler” identified as V. M. Atkinson is said to have told a similar croc story at the Leland Hotel in Chicago. But this time, the story was moved Egypt, and insead of locally leased babies, kidnapped

Jewish babies imported from Russia were supposedly used as bait.

Other details of the story are more-or-less the same as earlier versions, except that the Egyptian

hunters were not expert marksmen like the renowned British hunters in Ceylon or India; sometimes they missed.

Chicago, May 27. V. M. Atkinson, an English traveler who was

at the Leland yesterday, has recently visited Moscow and other Russian cities.

He declares that the Jews are persecuted most cruelly, and portrays a riot

where a dozen Jewish infants were torn from their mothers’ arms and thrown into

the streets. Mr. Atkinson says that

every stranger coming to Moscow who has a long nose is obliged to go before the

Russian authorities and prove that he is not a Jew. It appears that the Jews cannot leave Moscow

until they have signed a document stating that they have no pecuniary

obligations in the city. Mr. Atkinson

states that London philanthropists are endeavoring to get the Jews to emigrate

to the Arabian shores of the Red sea, and negotiations have been begun with the

Egyptian government.

A Shockingly Inhuman-Traffic.

“You have no Idea of the cruelty inflicted upon the poorer

classes of the Jews,” related the traveler. “For a year or so hundreds of babies have been

stolen and shipped to various ports on the Nile to be used as bait by the

crocodile hunters. Of course they are

not all eaten up by the animals, but now and then one is caught. The crocodile hunters place a baby on the

shores of the stream, and presently the lazy animals come out of their beds

after the infant. When the crocodiles get near the little one, and within

shooting range of the hunters, who are concealed in the bushes, they are shot. The little babes serve as a bait to bring the

animals on the bank.

The Government Runs the Press.

“By this means it is possible to get many animals that could

not be reached in any other way. It has

been said that the hunters have let the crocodiles approach too near the babes

before firing, and their first shot being ineffectual the little one was eaten

up. At any rate they are used for Bait. You think it queer that a wholesale kidnapping

of babies is not noticed in the newspapers. That is not strange. You don't know Russia.

The papers there can only print what the government approves of. If an editor gets any news that is sensational

he must first submit it to some official before using it. That is Russia.”

The Racine Daily Journal (Racine, Wisconsin), May 27, 1891, page 1.

Like the Kinghorn version, the Atkinson variant may have first

appeared in a Chicago newspaper. Most of the newspapers repeating the story list Chicago as its place of origin without naming the newspaper. On its earliest known

date of publication, May 27, 1891, it appeared in several newspapers in the

surrounding states of Wisconsin, Illinois and Indiana, so a Chicago origin is

not far-fetched. The story would

eventually appear in dozens of newspapers across the United States during every

month from May through September, and at least once in December.

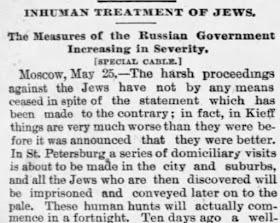

Although the switch from Ceylon to kidnapped Russian babies in Egypt may seem random, it may have been playing off real current events. In May of 1891, Russian Jews had already been widely covered in the news for actual atrocities, even before publication of Atkinson’s croc story.

|

| Chicago Tribune, April 23, 1891, page 5. |

|

| Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1891, page 5. |

It is almost as though a penny-a-line

“journalist” checked their annual calendar of story ideas and combined it with

current events to create a more sensationalistic story; one which is believable

precisely because of the brutal nature of the actual atrocities associated with

it, even if the fictional details are otherwise improbable and almost certainly

untrue.

Similarly, proponents of the literal

truth of the Chipley, Florida “alligator bait” more than a century later find

willing believers because the real history of slavery, failed Reconstruction,

Jim Crow, and Lynch Law make it seem plausible, despite the lack of actual

documentary evidence and obvious holes in what little “evidence” there is. But if true history is so compelling,

promoting false histories would not seem to serve any legitimate purpose. It may even undermine whatever rhetorical points

may be scored by circulating the rumor, due to a possible loss of credibility caused

by championing fictional embellishments which are improbable and almost

certainly untrue.

In another time and place, the crock about kidnapped Russian babies would make great “click bait,” even if it was not evidence of actual human “alligator bait.”

Loud Baby or a “Sulker”

A few years later, an alleged

“first-person” account appeared in the New

York Sun, and was picked up by dozens of other newspapers across the United

States. An unnamed “ex-officer of the

British army” is said to have described the “great sport in India going out

after crocodiles with Hindoo babies for bait.”

The story contains all of the familiar elements of the story, while

adding fresh details that add life to the story; a discussion about the relative

value of a loud baby over a “sulker,” and the “considerate sportsman’s” use of

a “nursing bottle, which is part of a crocodile hunter’s equipment.” He also claims to have tried, unsuccessfully,

to rent babies for an alligator hunt in Florida; “folks who owned babies down

there didn’t seem to enter into the spirit of the sport.”

“We used to have great sport in India going out after

crocodiles with Hindoo babies for bait,” said an ex-officer of the British

army. “The baby wasn’t baited on a hook

like a minnow or a fish worm, but simply secured on the river bank so that it

couldn’t creep or toddle away or tumble into the river. Some babies don’t like their being made

crocodile bait of, but that fact increased their value to the sportsman, for

then they yelled and made a great noise, which was just what the crocodiles

were waiting to hear, and they’d come hurrying from all directions to have a

chance at the babies.

“Where did we get these babies for bait? From their mothers. All the fellow who wanted to go crocodiling

had to do was to noise abroad his intention, and it wasn’t long before native

women would flock in with their babies to be rented out for bait. The ruling price per head for the young

heathen was about 6 cents per day. Some

mothers required a guarantee that the offspring should be returned safe and

sound, but most of them exacted no such agreement. The babies were brought back all right, as a

rule, but once in a while some sportsman was a trifle slow with his rifle, or

made a bad shot, and the crocodile got away with the bait, but that didn’t’

happen often.

“If your bait is in good form for crocodiling, and starts in

with protesting yells, you may expect to get your corocodile very soon, but if

the baby proves to be what is known as a sulker and takes the situation in

quietness and patience, you may have to wait some time before you get a

shot. I used to have the option on an

Indian baby that was the most killing bait for crocodiles in all that part of

India. I killed more than one hundred

crocodiles with that youngster as a lure before she outgrew her

usefulness. She had the most persistent

and far-reaching yell I ever heard come out of mortal being and no crocodile

could resist it. She was a real siren in

luring the reptiles to their fate, and I was sorry to see her grow and get too

big for bait and have to give her up.

That dusky infant always commanded premiums in market and her mother was

very proud of her indeed.

. . . A considerate sportsman, though, will not work his baby

more than fifteen minutes at a time.

Then he will have his native servant soothe it and refresh it from a

nursing bottle, which is part of a crocodile hunter’s equipment. I have killed six crocodiles over that

favorite baby lure of mine in less than a quarter of an hour.

“I was in Florida a year or so ago, and tried to hire a baby

to experiment with for alligators after the method in India, but folks who

owned babies down there didn’t seem to enter into the spirit of the sport, and

I couldn’t get one. I compromised on a

rather lively complaining dog. He was a

success, and I had quite a lot of fun, although the sport was a good deal tamer

than it would have been if I had only had a baby for bait.”

New York Sun,

June 24, 1894, page 24.

Pulitzer - Want Ads Revisited

In 1896, a new version of the Want Ad

variant of the story appeared in more than a dozen newspapers in various forms,

sometimes without the want ads and sometimes with an alternate image. The story must be true, as the copywriter

assured the reader that the supposed want ads were made, “in all

seriousness.”

The earliest example of this new

version appeared in Joseph Pulitzer’s New

York World, one of the newspapers, along with William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, that pioneered the

sensational style of news reporting known as “yellow journalism.”

Although the subject matter of

hunting crocodiles with babies as bait might otherwise seem disturbing, the

seriousness with which to take this version of the story may be informed by

other articles sharing space on the same page.

There’s that one about a tussle over possession of a “petrified man,”

between a team of museum archeologists and the son of a Canadian Voyageur named

Le Count who “literally” turned to stone after being shot in the chest by an

insane Englishman.

The New York World, August 16, 1896, page 23.

It must be true, as the copywriter

assured the reader that the story could “be proven by the elder son of Le

Count, who lives at Medicine Lake.”

And then there’s the one about the

man who “hangs himself for amusement” at Parisian

cafes in Montmartre for fourteen hours a day. It was perfectly

safe. The copywriter assured the reader

that an attending physician monitored his pulse, although he did cut the

initial attempt short at ninety-seven hours because, “to hang longer would be

extremely dangerous.”

It was 9 o’clock Sunday evening when Durand first hanged

himself. The café was crowded. He stepped upon the ladder, calmly adjusted

the noose and swung off into space. His

face soon began to grow red, then purple, and was soon almost black. His eyes were closed and the body swung

listlessly to and fro as if life were extinct. . . .

For ninety-seven hours Durand hung by the neck in the café-concert,

while the patrons indulged in rude jests about him and the singers squalled

from the little stage at the end of the room.

At the end of that time the physician watching him cut the rope, saying

that to hang longer would be extremely dangerous.

After resting a few hours Durand seemed no worse for his

experience, and since then he has been hanging himself for fourteen hours each

day.

The New York World, August 16, 1896, page 23.

Pulitzer’s version of the story revisits

familiar themes from other crocodile hunting stories, fat babies, loud babies,

accurate hunters, trusting parents, and babies more startled by gunfire than by

the approaching, open maw of a crocodile.

A good editor might have equally startled by the fact that the copywriter

confused a crocodile for an alligator in the first paragraph. The New

York World’s version differs from other versions, however, in that the

hunter was portrayed as ethnic Ceylonese rather than British.

Crocodiles like to eat babies – not their own awkward

offspring, but human darlings, fat and dimpled.

Skinny babies are not adapted to an alligator’s palate and are passed by

with scorn. But an alligator will crawl

a long distance for a fat one.

This liking of the saurian for babies is used by hunters in

Ceylon to lure the reptiles to death. A

nice, fat baby is tied by the leg to a stake near some pond or lagoon where

crocodiles abound. Soon the child begins

crying and the sound attracts the crocodiles within hearing distance. They start out immediately for the wailing

infant. . . .

THE BABY DOES NOT CARE.

A miss would mean death for the baby, but the hunters are

expert shots and at the short distance at which they fire a miss is next to

impossible. As a rule the sound of the

firearm scares the baby worse than the presence of the crocodile’s jaws and the

rows of sharp and glistening teeth, but after being shot over a few times the

child takes the shooting as a matter of course and pays little attention to

it.

So expert are many of the hunters that they do not shoot the

alligator until it has approached to within a few feet of the baby. Then, with but a few inches of space between

the muzzle of the rifle and the eye of the alligator, the shot is fired that

ends the existence of the reptile and saves the child.

WANTED – Some very fat children as bait for crocodile

hunting; we guarantee to return them safe and sound to the homes of the

parents. Apply to So and So.

This advertisement, which is inserted in all seriousness,

makes its appearance regularly in the Ceylon papers and is said to be

productive of good results. But those

Ceylonese mothers must be different from most mothers, or else they have a high

opinion of the ability and skill of the men who hunt crocodiles with human

bait.

The New York World, August 16, 1896, page 23.

|

| Image accompanying reprint of The New York World story, as it appeared in The Monroeville Breeze (Monroeville, Indiana), September 24, 1896, page 3. |

Sailor

Another crocodile-hunting story went

viral (by turn-of-the-century standards) about ten years later. This time it was written as a first-person

anecdote related by a sailor, and generally written in a Cockney-esque

dialect. This version appeared in

hundreds of newspapers between 1907 and 1916, and contained all of the standard

elements of the story, including lazy crocodiles, naked babies, and

sure-shots. But this time, instead of

haggling with the parents, there was a set price, 50 cents (or 2 shillings) a

day, with some parents earning as much as 2 dollars (or 8 dollars) a week. Why not, it wasn’t dangerous.

“Of course,” the sailor went on,” the thing ain’t as cruel as

it sounds. No harm ever comes to the

babies, or else, o’course, their mothers would not rent ‘em. The kids is simply sot on the soft mud bank of a crocodile stream,

and the hunter lays hid near them, a sure protection.

“The crocodile is lazy.

He basks in the sun in midstream.

Nothin’ will draw him in to shore, where ye can pot him. But set a little fat naked baby on the bank

and the crocodile soon rouses up. In he

comes, a greedy look in his dull eyes, and then ye open fire.

“I have got as many as four crocodiles with one baby in a

morning’s fishin’. Some Cingalese women

wot lives near good crocodile streams make as much as two dollars a week

reg’lar out o’ rentin’ their babies for crocodile bait.

The Journal and Tribune (Knoxville, Tennessee), October 6, 1907, page 18.

Hearst’s “French

Traveller”

At least one further variant of

Robley’s original crocodile-hunting story appeared before T. W. Villiers’ frequently-cited

“news” item of 1923. It appeared in

William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco

Examiner (and at least one other newspaper[xi])

in 1908. Hearst’s version moves the

action from the Indian Sub-Continent and neighboring islands to Sudan in

Northern Africa; but the song remained the same. Based on a purported eye-witness account by a

“French traveler,” and supported by several photographs illustrating the

action, one might imagine Hearst paraphrasing himself a decade earlier, “you

furnish the pictures; I’ll furnish the story.”

Hearst’s account revisits most of the

standard themes, but with some new details.

Instead of tying the baby up next to the water, it is placed fifty yards

away, so that the crocodile leaves the water, making it easier to catch. And this time it’s the locals using their own

babies as bait, not some “Great White Hunter,” and instead of rifles they used

spears, and instead of infallible hunters the babies sometimes die, which

(purportedly) “causes little excitement in a Soudanese community, where human

life is held cheap.”

Aside from its being the umpteenth

version of the same old story, and suffering from Hearst’s reputation for

sensationalism, the story, as written and portrayed in images, has other problems. The one photograph of the supposed crocodile

hunt bears no resemblance to the description of the hunt as described; no baby,

no spears in hand, and at the water’s edge, not forty yards inland.

It is extremely difficult to catch the crocodile by any sort

of bait or trap, for he is highly suspicious, and as soon as he detects the

handiwork of man he makes for the water.

“There is one bait, however, that the crocodile can never

resist, and that is a live human baby.

As soon as he hears the squeals of a child he throws caution to the

winds and dashes for his tender prey.

Shocking as it must appear, the African natives take advantage of this

fact, and frequently use their own babies as bait for crocodiles.

The natives tie a large, vigorous baby to a stake at a distance

of fifty yards or so from the river.

They then go a short distance away and hide themselves behind bushes,

rocks and other obstacles. The poor

baby, finding himself left alone and tied up, naturally, begins to cry, He has

been chosen on account of his size and vigorous lung-power and his cries are

certain to be heard by any crocodile within a mile or so.

The first crocodile who hears the cries dashes out of the

water and comes running up the ban, his mouth watering at the thought of the

meal that awaits him. The baby has been

purposely tied at a greater distance from the water than the crocodile is

accustomed to venture, but in his ravenous desire for human flesh he forgets

all about this.

Soon the crocodile arrives within five or ten yards of the screaming

baby. A snap of his cruel jaws will

swallow the baby as easily as a man would swallow a cherry. His fierce little eyes glitter with

greediness.

Then the natives spring from their hiding place and attack

the crocodile with their spears. With

wonderful dexterity they avoid the snapping of the huge jaws and the lashing of

the great tail that would knock down a horse.

Working in unison, they turn the crocodile on his back and then plunge

their spears through the soft skin of the underbody into his heart and lungs.

Sometimes, owing to the fact that a number of crocodiles come

at once, or to some other accident, the poor baby is lost, but this accident

causes little excitement in a Soudanese community, where human life is held

cheap.

San Francisco Examiner, October 18, 1908, American Magazine Section; Billings Gazette (Billings, Montana),

February 11, 1909, page 2.

The details of tying up the bait far

from the water and using hand-held weapons to subdue the crocodile could easily

have been borrowed from a more plausible account of an alligator hunt that

appeared in the Chicago Inter-Ocean,

the New York Sun and several other

newspapers nearly a decade earlier, illustrating how a newspaper copywriter

might cobble-together elements from different stories to craft their own

version of an earlier hoax. And the Chicago Inter-Ocean article itself is

nearly identical to an article first published in the Chicago Times another decade earlier, in 1890, further illustrating

how “journalists” of the time repackaged and repurposed old content as new,

making it difficult at times to sort out fact from fiction.

In an article dateline Magnolia

Plantation, North Carolina, August 7, 1900, a “special correspondent” of the Chicago Inter-Ocean described an

alligator hunt he witnessed on the Waucamaw River (he described it as the

Waccamucca) near the South Carolina border.

In an article published in February 1890, a “correspondent of the Chicago Times” gave an account of an

alligator hunt he witnessed on the “Waccamucca River” near Alligator Swamp,

North Carolina.[xii]

It is not clear precisely where the

story took place. There is no

“Waccamucca River” on current maps.

However, the Alligator Swamp is an actual location in Waccamaw, North

Carolina, and the nearby Waccamaw River flows into South Carolina, about twenty

miles further south.

In both accounts, the author is

travelling with a companion (“Denton” in 1890, “Gregory” in 1900) and an

African-American guide (“Caleb” in 1890) and (“Pete” in 1900), but in all other

details the stories are identical.

The group is crossing the

“Waccamucca” river on a ferry when they hear a loud commotion. The ferryman, a black man named Joe, tells

them that group of locals are trying to capture a large alligator that had

recently eaten several pigs a calf.

The group goes to investigate and finds

a dozen men and boys who, like Hearst’s Sudanese crocodile hunters years later,

are “armed with clubs, poles, and axes” and surrounding an alligator on open

ground, about one hundred yards away from the water. They had lured the alligator away from the

water with a “half-grown puppy” tied “to a small tree about 200 yards from the

water.” Alligators, they explained, “are

extremely fond of dog meat, and they will follow a dog far into the fields or

swamp with the hope of catching him.”[xiii]

Ten and twenty years after

publication of the two Waccamucca alligator hunting stories, Hearst’s “French

traveler” version moves the action to Sudan, replaces the dog with a baby, and

substitutes spears with clubs, poles and axes.

Fifteen years after Hearst’s version, T. W. Villiers moved the action to

Florida, swapped out the crocodile for an alligator, and instead of tying the

baby far enough from shore to expose the alligator, placed the baby in shallow

water far enough from deep water to force the alligator “above the surface,

wading toward the ‘bait’ with his head and forequarters well ex-posed.” But the change in distance makes sense in

context, if Villiers’ story is to be given any credence, because Florida

marksmen “never miss” and do not need to be as far from the water as people

hunting with spears or clubs, poles and axes.

The dramatic elements of Villiers’

1923 version were also essentially unchanged from the Robley’s original 1888

“crocodile bait” story; a hunter negotiates with parents, the parents place an

irrational trust in expert skill of the hunter, the babies are best used naked

and fat babies, crocodiles and alligators are generally lazy and difficult to

find, but have an irrepressible appetite for babies (sometimes a specific

appetite for black babies over white), and the hunter is portrayed as

infallible, never missing a shot. But

even if Robley’s story is responsible for launching a string of imitators, his

story might have been influenced by a much older acount about crocodile hunting

in Egypt

Benoit de Maillet was a French

diplomat and naturalist who spent sixteen years as the French general consul in

Egypt. Maillet’s anonymous and

posthumously published work, Telliamed

(his name backwords), contained one of the earliest, pre-Darwinian scientific

speculations about evolution and the origin of species. But in 1735, three years before his death, he

published a less controversial book about Egypt, which included a section about

the dangers of crocodiles.

Maillet described several common ways

in which Egyptians hunted crocodiles.

They dug ditches and covered them with straw, for crocodiles to fall

into; they set snares; or they baited hooks with a quarter of a pig or with

bacon. Maillet also described one

unusual, more sensational method which may have been used only one time.

One of the inhabitants of the Upper Egypt took one of them,

the last year, in a manner which deserves to be mentioned, both on account of

its singularity, and the danger to which the man exposed himself. He placed a very young boy, which he had, in

the spot where the day before this animal had devoured a girl of fifteen,

belonging to the governor of this place, who had promised a reward to any one

that should bring him the crocodile dead or alive. The man at the same time concealed himself

very near the child, holding a large board in his hand, in readiness to execute

his design. As soon as he perceived the

crocodile was got near the child, he pushed his board into the open mouth of

the creature, upon which his sharp teeth, which cross each other, entered into

this board with such violence that he could not disengage them, so that it was impossible

for him after that to open his mouth.

The man immediately further secured his mouth, and by this means got the

fifty crowns the governor promised to whosever could take this creature.

Benoit de Maillet, Description de l’Egypte, Paris, Quay des

Augustins, 1735, Lettre Neuvieme, page 32-33 (English translation from Thomas

Harmer, Observations on divers passages

of Scripture, volume 4, London, J. Johnson, 1787, pages 288-289).

Maillet wrote in French, but English

translations were available and kept alive for decades, frequently in books

mixing scripture with first-hand observations of life in the Middle East in an

attempt to reconcile biblical text with the real world. In his book Observations on divers passages of Scripture, an English minister

named Thomas Harmer used Maillet’s crocodile writings as support for his speculation

that “crocodile” would be a better fit for “whale” in English translations of

the bible. In Book of Job, for example, he felt that “Am I a sea, or a whale,”

would make more sense if translated as, “Am I a sea, or a crocodile.” Further, he believed that that Maillet’s

account of crocodile hunting was consistent with the idea that people in the

region might “set a watch over” a crocodile, as suggested in Job.

Maillet’s story was kept alive

through at least four printings of Harmer’s work, one every ten years after the

original date of publication. The story stayed in circulation in similar books

building on Harmer’s religious theories, like Richard J. Martin’s Sacred Zoology[xiv]

and The Bible Expositor[xv]

published by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, and others,

quoting Harmer extensively.

For more than 150 years stories about

baiting crocodiles with young children were confined, for the most part, to

obscure religious texts. That all

changed in 1888, with the publication of several similar “crocodile bait”

stories in quick succession, which were then kept alive for decades in a string

of copycat versions before culminating in perhaps its least plausible, but

perhaps most believed, version, T. W. Villiers’ 1923 opus about supposed

alligator hunting techniques in Chipley, Florida.

The Bronx Zoo

The second most frequently cited

article cited as “evidence” of the truth of the rumors that children were used

as alligator bait is a 1908 article describing the scene at the Bronx zoo when

moving the alligators from their indoor winter quarters to their outdoor summer

quarters.

Their greedy eyes eagerly fixed on two plump pickaninnies,

the crocodiles and alligators in the New York Zoological Garden were decoyed

from their winter quarters in the reptile house to the cool and shady tank just

outside the building.

It was the keeper’s idea to bait the saurians with

pickaninnies, knowing as he did their epicurean fondness for the black

man. So as two small colored children

happened to drift through the reptile house among the throng of visitors he

pressed them into service.

The two crocodiles and all but four of the twenty-five

alligators wobbled out as quick as they could after the ebony mites, who darted

around the tank just as the pursuing monsters fell with grunts of chagrin into

the water, disappointed of their prey.

Washington Times (Washington DC), June 13, 1908, page 2.

Outdoor Alligator Pool, Popular Official Guide to the New York

Zoological Park, 12th Edition, 1913.

The New York Times story about the same event, published the same day, paints a less

controversial picture.

Equipped with poles and ropes, Head Keeper Snyder, assisted

by Keeper Toomey and some men drawing moving cages, approached the reptile

house at 2 o’clock and commenced their task.

The small alligators came out willingly into the cage after a prod from

the long sticks, but the older ones had to be lassoed and yanked out by force. As the unwieldly creatures, fighting every

inch of the way, slid down the plank with a rush into the pond, the children

screamed with delight, and wanted Snyder to do it all over again.

New York Times,

June 13, 1908, page 1.