A version of this article first appeared in print as, “Biography of Robert Sale Hill,” Peter Reitan, Comments on Etymology (edited by Gerald Cohen, Missouri University of Science & Technology), Volume 50, Number 8, May 2021, page 11.

Robert Sale Hill introduced the word “Dude” into the language with his poem, The True History and Origin of the “Dude,” first published in January 1883. The poem satirized the frivolous, idle young sons of America’s Gilded Age millionaires as silly, weak-minded and physically weak Anglophiles, who wore imported clothing, affected British mannerisms and speech patterns, and avoided physical activity.

Robert Sale Hill bore a passing resemblance to the people he mocked. He was a young man of thirty-two at the time, ran in the same social circles, came from a family with money, social standing and prestige, and spoke with an “indistinct utterance which is neither English nor American.”

But the similarities ended there. He was not stupid, idle or lazy. He had success as an actor, poet, writer, athlete, investor, entrepreneur, customs official, international banker and international broker. He was involved in at least one broken engagement, which may have made him seem frivolous, but he married that same woman after the death of his first wife ten years later, so perhaps he wasn’t as frivolous as it may have seemed at the time. And whereas the original “Dudes” merely affected the manners, dress and speech of the Englishmen they admired, he came by his “indistinct” accent honestly.

Robert Sale Hill was an Irish-born Englishman, with generations of family history in Northern Ireland on his father’s side of his family (the Hills), and generations of family history in India on his mother’s side (the Sales). The Hills were connected to a hereditary title with estates near Londonderry, Northern Ireland. The Sales were connected to several generations of military officers and bureaucrats of the East India Company. Robert Sale Hill was born Dublin, Ireland, educated in Berkshire, England, and lived in London, New York City, Helena, Montana, Tacoma, Washington and Hong Kong, before returning to London. He died on the Island of Jersey in 1922.

The Hills of Ireland

Samuel Hill, the first of the Hills in Ireland, moved there from Buckinghamshire in about 1642, to serve as the Treasurer of Ireland under Oliver Cromwell. In 1779, King George III awarded Robert’s great-grandfather, Sir Hugh Hill, the hereditary title of the 1st Baronet, of Brook Hall. His estate included 230 acres of land in County Londonderry, 969 acres in County Donegal, with “seats” at Brook Hall in Culmore and St. Columb’s Cathedral in Derry. The Brook Hall Estates were sold to the Gilliland family in 1852, but the baronetage has passed down for eleven generations. Robert Sale Hill’s uncle George was the 3rd Baronet, and his first-cousin Major Sir John Hill was the 4th Baronet. Sir John Alfred Rowley Hill is currently the 11th Hill.i

The Hill Baronets had a coat of arms and a motto. The coat-of-arms included a “chevron erminois between three leopards’ faces” below a crest of a “talbot’s head,” with a studded collar. The motto, “Ne Tentes aut Perfice,” translates loosely as the Yoda-esque expression, “Perfect, or never try, your plan” (“Do or do not; there is no try.” – Yoda.).

Ne tentes, aut perfice.

If you ascend the hill of strife,

Or journey down the vale of life;

Whether you climb th’ adventurous steep,

Or boldly o’er the ocean sweep,

Or calmly on its surface creep,

‘Tis perseverance proves the man.

“Perfect, or never try, your plan.”

Amicus, A Translation, in Verse, of the Mottos of the English Nobility and Sixteen Peers of Scotland, in the Year 1800, London, Robert Triphook, 1822, page 38.

The Hill family also included prominent clergymen. Robert Sale-Hill’s grandfather, Reverend John Beresford Hill, a son of the 1st Baronet, missed out on the title due to his birth order, but became the Prebendary of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, the national cathedral of the Church of Ireland.

Reverend John Beresford Hill’s older brother, Sir George Fitzgerald Hill, the 2nd Baronet, served at various times as Clerk of the Irish House of Commons, Colonel in the Londonderry Militia, Lord of Treasury for Ireland, Vice-Treasurer of Ireland and the Governor of St. Vincent and Trinidad. But when he died without an heir, the title passed to his nephew and namesake, the Rev. John Beresford Hill’s oldest son, Sir George Hill, the 3rd Baronet. This placed Reverend Beresford Hill in the rare position of being the son of, brother to and father of a Baronet, without having been a Baronet himself.

Reverend Beresford Hill’s grandson (Robert Sale Hill’s first-cousin), the Right Reverend Rowley Hill (a son of the 3rd Baronet), also missed out on the hereditary title due to his birth order, but held the religious titles of Vicar at Sheffield, Bishop of Sodor and Man, and the Canon of York. His brother, Major Sir John Hill, became the 4th Baronet.

The Hill family also included someone with a non-hereditary title. Robert Sale Hill’s brother, Rowley Sale Sale-Hill, followed in his father’s footsteps in the military, rising to the rank of General and being made a Knight Companion in the Order of Bath. Curiously, Sir Sale-Hill and his son (another decorated military officer) were made the subjects of a small newspaper filler of no apparent news interest that was widely reprinted throughout the United States in 1903.

Sir Rowley Sale Hill is one of Britain’s most popular old war veterans. He joined the Bengal army in 1856 and served through the terrible Indian mutiny. He also served under Lord Roberts in Afghanistan. His one boy, a chip of the old block, lately got five clasps to his South African medal.

The Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), June 20, 1903, page 4 (and many other newspapers).

Sir Rowley Sale Sale-Hill used the same motto as, and a coat-of-arms nearly identical to, the ones associated with his cousin’s Baronetcy.

Robert Sale Hill did not have a title, a coat-of-arms, or a motto, but the cover-art on his original “Dude” poem included a coat-of-arms with a dodo and an ass instead of a Talbot and jaguar, a top hat instead of a knight’s helmet, dollar signs instead of ermine tails, and a motto (“much money, but little brains”) that sounds more like something out of Spaceballs than Star Wars. He may have been making fun of the silly trappings of his own family’s aristocratic lineage, as well as the American “Dudes” who affected the silly trappings of British aristocracy.

|

Detail from the cover art of The History and Origin of the Dude. The motto reads (in French), “Much money, but little brains.” |

A poem he published several years later may shed some light on his personal attitude toward inherited titles, wealth and fame.

Life’s Highest Title.

Life’s but a span. The tidal wave of death

Sweeps down all barriers of wealth and fame.

And levels every thing with icy breath,

Leaving to rich, and poor alike, a name.

“What’s in a name” bequeathed through dead men’s deeds,

If the recipient lets its luster wane?

The rarest flower may be raised by seeds

But ‘tis the gardener’s skill which rears the same.

What’s in a title? Accidental birth

Oft gives the proudest rank to idle mind,

While honest poverty may prove its worth

By rising to be ruler o’er mankind,

What then are titles, wealth, or worldly fame,

Thrown in the balance with eternity?

They crumble like the dust from which they came,

And seek the region of obscurity.

Be your own gardener, then, and weed the soil

Which God hath given. So it if you can,

For when Death scatters all your years of toil

He leaves unscathed God’s highest title:

“Man.” – Robert Sale Hill, in America.

The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), December 22, 1890, page 3.ii

The Sales of India

The Sale side of Robert Sale Hill’s family lacked a direct connection to a hereditary title, although his mother’s aunt Frances married one – the 7th Baronet of Roydon Hall. But even without inherited titles, his mother’s parents earned titles for military action in Afghanistan, after a long career with action in India, Burma, and Mauritius.

Born in 1782, his grandfather, Colonel Robert Henry Sale, joined the 26th Regiment of Foot (infantry) as an Ensign in 1795, at the age of 13. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1798, transferred to the 12th Regiment of Foot in 1798, and promoted to Captain in 1806 and major in 1813. He was transferred to the 13th Regiment of Foot in 1821, where he spent the rest of his career. He was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1825, Colonel in 1838, and brevetted to the local rank of Major-General in India in 1839.iii

Colonel Sale was known as “Fighting Bob Sale” and the “Hero of Jalalabad.” He was knighted twice over, as Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1839, and again as Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1842, following his actions in withstanding and eventually breaking the Siege of Jalalabad.

Streaming after the colours With “Fighting Bob” we go,

Our step is firm, our spirits light, To smash up our dusky foe.

Jellalabad can’t hold us, We’re ready for any deed,

We’ll follow the colours quickly, We’re of the British breed.

Hampshire Telegraph and Naval Chronicle (Portsmouth, England), March 21, 1885, page 10.

A poem written in his honor following his death in India, in action against the Sikhs in 1846, also identifies his wife as a hero.

Thou too, right valiant English heart,

That ‘mid the conquering foe,

Though woman, playedst the hero’s part,

Still darker hours must know.

If prayers and tears could purchase life,

A nation’s might avail,

And give thee, glorious from the strife,

Once more to welcome Sale.

“On the Death of Sir Robert Sale, Killed in Action Against the Sikhs,” The Weekly Standard and Express, March 11, 1846, page 4.

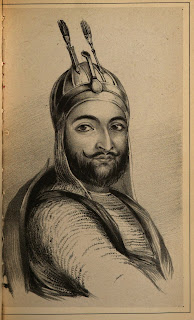

Robert Sale Hill’s maternal grandmother, the Lady Sale (born Florentia Wynch), was known as “heroine of Cabul.”iv While Colonel Sale was under siege in Jalalabad, his wife stayed behind in Kabul, Afghanistan where she witnessed and what was arguably the greatest military catastrophe in British history, when nearly “the entire force of 690 British soldiers, 2,840 Indian soldiers and 12,000 followers were killed”v in the retreat from Kabul. A small number of people, mostly officers and their wives – about 100 in total, were spared by being taken prisoner of Akbar Khan and held as hostages for nine months. Lady Sale and her daughter Alexandrina were among the hostages, but only after Lady Sale was shot in the wrist while fleeing with the troops on horseback, and her daughter’s husband, Lieutenant Sturt, was killed.

Lady Sale’s journal entries and letters became part of the official history of the war, and were collected and published as a popular account of the war after her return to England. Of her, it was said that, “She showed such intelligence, judgment and firmness that so excellent an authority as the Duke of Wellington said that if she had been in command the army would not have been lost. She was not in command, however, and routine generals, who blindly trusted the treacherous Afghans, went headlong on to disaster.”vi

|

| Akbar Khan, sketched by Lieutenant Vincent Eyre.vii |

She also showed poise under pressure. When Akhbar Khan asked her to write to General Nott, to ask him not to advance toward Kabul, “the heroine immediately wrote, ‘Advance Nott!’”viii

After her release from captivity, someone wrote a song in her honor.

“Lady Sale. – ‘Come, weave the laurel wreath for her,’ NEW SONG, written on the heroic conduct of Lady Sale in Affghanistan, by Edward J. Gill.”ix

Come, Weave the Laurel Wreath for Her!

Hark! Through the mountain pass the trumpet rings,

While fell destruction hovers on its wings.

Like serpent stealing, see, the Indian creeps,

And Britain’s bravest ‘neath the cold turf sleeps!

Yet woman bids defiance to the band,

And “No Surrender” echoes through the land;

Once more awake the sounds with vengeance rife.

For Britain triumphs in the glorious strife.

J. Diprose, Diprose’s Royal Song Book, Third Edition, London, J. Diprose, 1845, page 35.

When Sir Robert and Lady Sale returned “home” shortly after her release from captivity, they were celebrated as national heroes. At a formal dinner in their honor, she wore a turban, perhaps one similar to one she was sketched wearing while in captivity.

|

| Lady Sale, sketched by Lieutenant Vincent Eyre.x |

[T]hey suddenly struck up “See the conquering hero comes,” and immediately afterwards a tall thin lady, robed in black, with a white turban on her head . . . entered the gallery, and the whole company rose and received with acclamations the heroine of the Khyber Pass and Gundamuck – the noble-minded, English-hearted Lady Sale.

Berrow’s Worcester Journal (Worcestershire, England), August 22, 1844, page 1.

It may, however, be a misnomer to refer to England as their “home.” They had both spent most of their careers and lives in India, and both came from families who had been in India for multiple generations.

Sir Robert Henry Sale was the son of a Colonel R. Sale, who was “for many years an active officer of the East India Company.”xi The elder Colonel Sale served as the “Commander at Vellore”xii and died there in 1799.xiii The nickname of the city of Vellore is “Second Madras,” because of its proximity to the city of Madras (now known officially as Chenmai), where his wife’s family had lived for generations.

Lady Sale’s father, George Wynch, lived in Fort St. George in Madras (now the seat of the Tamil Nadu legislature) as early as 1855.xiv He later held some responsible administrative positions with the East India Company in Madras.xv

Her grandfather, Alexander Wynch, was in India as early as 1737,xvi and later served as the Governor of Madras. Her grandmother, Alexander Wynch’s first wife Sophia, was the daughter of Edward Croke, the Governor of Fort St. David, about 100 miles south of Madras.xvii When her great-aunt (Sophia’s sister, Begum Johnson) died in Calcutta in 1812, she was memorialized as “the oldest British resident in Bengal, universally beloved, respected and revered.”xviii Their mother, Lady Sale’s great-grandmother Isabella (nee Beizor) Croke, was an Indian-born Portuguese woman who may (or may not) have had some Indian ancestry.xix

Lady Sale did, however, spend a significant amount of time in Britain as a child, so she wasn’t completely unfamiliar with her nominal homeland. She returned from India with her father in 1799xx to live at his estate in Clemenstone, in Glamorganshire Wales.xxi King George III appointed her father to serve as Sherriff of Glamorganshire in 1807.xxii And she was educated at “one of the first seminaries in London.” She educated her five daughters in India, including Mrs. Sturt, who spent nine months in captivity with her, and Robert Sale Hill’s mother, Catharine, who married Captain Rowley John Hill. xxiii

Colonel and Lady Sale returned to India following their brief stay in England. He died in combat in the “Battle of Mudke”a few years later, in December 1845. She is said to have had the opportunity to leave their home base at Ambala due to the risk of attack, but “said she would remain and share the fate of the last soldier’s wife there.”xxiv Despite her husband’s death, the British won the battle and she did not have to share his fate.

She remained in her adopted homeland for nearly a decade after her husband’s death. She left India for health reasons in 1853, and died shortly after arriving in South Africa.

Robert Sale-Hill’s father, Rowley John Hill, was born in 1806, the second son of the Reverend John Beresford Hill. Like his father and nephew, he missed out on the Baronetcy awarded to his brother George, pursuing a career in the military instead, spending nearly his entire career with the 4th Regiment, Native Infantry, in northern India and Pakistan.

Rowley John Hill was made an Ensign in the army in 1828, and in 1829 was attached to the 4th Regiment, Native Infantry (NI), stationed in Oudh, in northeastern India. In 1839, “Ensign Rowley Hill, of the 4th Regiment Native Infantry” was reassigned from “the 1st Regiment of Infantry to the 1st Regiment of Cavalry, in the Oude Auxilliary Force as subaltern.” xxv He was still in the cavalry in 1842 when his wife, “the lady of Capt. Rowley Hill, 6th Irregular Cavalry” gave birth to their fourth child in Ambala.xxvi In early 1849, he was the “2d in Comd. – Acting Comdt., 6th Irregular Cavalry, Saugor.” He arrived at his final duty station at Rawalpindi, Pakistan, in December 1849.

The circumstances or cause of his death are unclear, but Captain Hill died in Bombay, India in November 1850, less than a month after his son Robert was born. It is not known when or why his mother moved back to Britain, but she was at her sister-in-law’s home in Ireland when she gave birth to her son Robert in October 1850.

Robert Sale Hill in Britain

Robert Sale Hill was born in Ireland on October 11, 1850, the fifth child of Captain John Rowley Hill and Caroline Catherine Sale. Since his father spent his entire career in India and Pakistan, and their fourth child was born in India, Robert was likely the first child in several generations, on either side of his family, to be born in Britain.

Births. . . . On the 11th inst., at Granite-lodge, Kingstown, the lady of Captain Rowley Hill, commanding 5th Irregular Cavalry, Mooltan, of a son.

The Morning Chronicle (London), October 16, 1850, page 8.

Robert was born at “Granite Lodge,” Kingstown, Ireland (now know as of Dún Laoghaire), in County Dublin, Ireland. The “Granite Lodge” was the home of his uncle, Joseph Tromperant Potts, Esq., who was married to Rev. John Beresford Hill’s first-born daughter, Mary.xxvii The Granite Lodge was (and may still be)xxviii located at the southwest corner of Lower Glenageary Road where Corrig Road turns into Eden Road. xxix If the original house, or any portion of it, is still standing on that corner, it may be considered the home of the “Dude.”

Robert Sale Hill attended a boarding school in Crowthorne, England. He enrolled at Wellington College during the Lent Term of 1862,xxx and stayed through the summer of 1867.xxxi The school was “specifically founded to provide an almost-free education for the sons of Army officers who died while serving, and although it also admitted other students, these ‘Foundationers’ as they were called made up a large part of the student intake.” Robert was admitted as a “Foundationer” and paid only “£10 per year when the full fees were £80 to £100 per year.”xxxii

While at Wellington, Robert lived in Beresford Dormitory, named after William Beresford, 1st Viscount Beresford of Beresford.xxxiii Robert was a 2nd Cousin, 3x removed, of the Viscount, through his grandfather’s (Reverend John Beresford Hill) grandmother (Sophia Beresford Lowther), the wife of Sir Hugh Hill, 1st Baronet. The connection may, however, have been merely coincidental. Robert was nominated for his spot in the school by Edward Law, 1st Earl of Ellenborough, who served as the Governor-General of India from 1842 through 1844, during the time Colonel and Lady Sale became famous for their exploits in Afghanistan.

When Robert attended Wellington, “the College was divided into the ‘Classical School’, in which boys learned more Latin and Greek, and the ‘Mathematical School’, in which they learned more modern subjects such as Maths and modern languages, although still some Classics. Robert was in the Mathematical School,”xxxiv which may explain his success later in building his nest egg on Wall Street (although marrying the daughter of a Wall Street broker may also explain some of that nest egg).

The school does not have any record of his athletic or artistic accomplishments at school, but the school presumably helped lay the foundation for his success years later, as an athlete, writer and actor.

During his stay at Wellington, his mother listed her address as “St. Leonard’s, Penge, Surrey.”xxxv “St. Leonard’s,” sometimes referred to as “St. Leonard’s House,” appears to have been the name of a residence, not a church or convent as its name might suggest. It was located at the intersection of “Adelaide-road and Penge-lane,” which apparently correspond to Queen Adelaide Road and Penge Lane, in the neighborhood of Penge, on a current map of the city.xxxvi As of May 2021, a Nepalese and Indian restaurant called Himalayan Kitchen stands on that corner. If his mother Caroline were to return today, she might feel at home with the types of food she may have become accustomed to during her time in northern India with her husband, Captain Rowley John Hill.

It’s not clear whether she owned or rented, but a partial description of the home suggests that St. Leonard’s may have been large enough to accommodate more than one family.

Three substantially built, detached residences, situate close to the Railway Station, including St. Leonard’s House, possessing ample accommodation for a family, and having nine bed and dressing rooms, three reception rooms and a large . . . .

London Evening Standard, October 2, 1879.

St. Leonard’s House appears (at least at one time) to have been under common ownership with a number of other buildings on the same block. In 1882, someone advertised an auction of leasehold estates for “22 private residence, Nos. 1 to 20 Queen Adelaide Road and St. Leonard’s House and Hamilton House, whole producing £1400 per annum.”

In any case, it is not known when Caroline Sale Hill left Ireland, how long she stayed in London, or when she left. She died in Bedford, England in 1890. Because of her position as a generational bridge between two prominent military officers, her death was considered newsworthy, and reports of her death even made it into some American newspapers.

Mrs. Caroline Catherine Hill, second daughter of the late General Sir Robert Sale, G.C.B., whose gallant defense of Jellalabad against the Afghans nearly half a century ago was the one redeeming feature of the take of our terrible disasters in the passes of Cabul, and whose wife, Lady Sale (Mrs. Hill’s mother), a captive in the hands of the Afghans, wrote a thrilling narrative of the sufferings of herself and her fellow-captives during their memorable adventures. Mrs. Hill’s husband was Captain Rowley John Hill, an officer in the Bengal Irregular Cavalry. Her marriage was celebrated on January 2d, 1835, and she became a widow in November of 1850. The second of her four sons is Lieutenant-General Rowley Sale-Hill, C.B., a distinguished officer of the Bengal army who is engaged in the task of defending the military reputation of his grandfather, the hero of Jellalabad.

The Leeds Mercury (West Yorkshire, England), August 12, 1890, page 5; Baltimore Sun, August 28, 1890, page 3.

As for her son, Robert, he disappears from the historical record after leaving Wellington College in the summer of 1867 and reappears a decade later in New York.

New York City

In what may be the earliest reference in print to Robert Sale Hill, he is a bit player, the “first walking gentleman,”xxxvii in the stock acting company of the Academy of Music in Buffalo, New York.

Academy of Music.

The Company and the Stars for the Coming Season.

The regular dramatic season at the Academy of Music will open on the 18th inst., with Mr. Lester Wallack in the beautiful drama of ‘Rosedale.’ The lessees, attaches, members of the dramatic company, and the stars and combinations already engaged for the season are as follows:

. . .

E. A. Locke, comedian.

George B. Waldron, leading heavies and character.

J. E. Egberts, leading juvenile.

J. B. Everham, first old man.

E. E. Eberly, second old man.

R. S. Hill, first walking gent. . . .

Buffalo Evening Post, September 9, 1876, page 3.

Although not identified by name here, the reference to “R. S. Hill, first walking gent,” is consistent with a description of Robert Sale Hill’s early professional acting career as the “second walking gentleman” at Daly’s Theatre in New York City.

An example of how amateur theatricals lift men into social prominence is furnished by Robert Sale Hill. He now spends his summers at Newport, and is quite the go everywhere. No amateur performance is considered perfect without him. On the stage, he has the ease of a Bowery clothing dummy and the grace of a manikin. He has always been fond of acting, and once enjoyed a brilliant theatrical career as “second walking gentlemen” in Daly’s Theatre. He was then known as Bob Hill. His acting consisted in walking in from the wings clad in a square-cut and woodeny frockcoat, recently ironed breeches, gorgeous patent-leather boots, waxed moustache, and well-plastered hair. He went down into Wall street and made money. He is at bottom a genial, good-hearted and generous fellow, and well liked among his friends. He plays cricket with some swell young Englishmen, and has acquired the manners of an actor off the stage. He seems to be perpetually on parade. Every night he is rehearsing somewhere, and he probably appears in twenty plays during the season. He is the best known of our amateur actors in New York.

The Times-Democrat (New Orleans), February 17, 1884, page 4.

He may have arrived in the United States even earlier, and performed in places other than New York State. A review of a satirical performance of “Hamlet” in 1874 in New Orleans, for example (the character of Claudius is referred to as the “Carpet-bag King of Louisiana”), lists an actor named “R. S. Hill” in one of the “other roles.”xxxviii In 1877, a man named “R. S. Hill” appeared in Toronto, Canada as a member of Warde & Herbert’s English-Comedy Company.xxxix

If Robert Sale Hill were not already based out of New York City before 1877, his association with Warde & Herbert’s would have given him an opportunity to get to the city. Fred B. Warde, one of the managers of Warde & Herbert’s, was a serious actor. In 1876, he was described as the “Leading Tragedian, Booth’s Theatre, N. Y.,” and played De Mauprat opposite Edwin Booth’s Richelieu and Othello opposite Edwin Booth’s Iago in a touring company with Edwin Booth.

By 1883, Robert Sale Hill was no longer a professional actor. He had reportedly made some money on Wall Street and had become part of the social set; summering at Newport and Lenox, and acting alongside Cora Urquhart Potter, the wife of financier James Brown Potter, of the investment bank Brown Brothers & Co.

Mrs. Potter and her informal company of amateur actors performed regularly at charity events in New York City. Robert Sale Hill performed with her at events to raise money the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund (to build the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty),xl the Home for the Destitute Blind,xli the “Hampton schools” (a boarding school for Native American children),xlii the New York Orthopedic Dispensary and Hospital for Crippled Children,”xliii and a charity that provided “a home for the poor girls who work in the factories and places of like nature, and others of their class are in the evening taught the various duties of housekeeper.”xliv

They also took their show on the road, performing in Pittsfield and Lenox, Massachusetts during the Berkshires season. At a benefit for the “House of Mercy, the only hospital in the Berkshires,” Robert Sale Hill did what he was unable to do as a professional; he played the lead, as the Marquis in Feuillet’s “The Portraits of the Marquise,” in which he gave a “finished and elegant interpretation of the part of the Marquis.”xlv

He also played the lead in several performances of “Romance of a Poor Young Man,” and the male lead in “The Moonlight Marriage,” opposite Mrs. Potter. Ironically, the same week the originator of the “Dude” performed “Romance of a Poor Young Man” at the Madison Club Theatre, a man named George Riddle (described as an “accomplished and delightful reader) performed a sketch entitled, “A Cure for Dudes,” in the same theater.xlvi The sketch, written by John T. Wheelwright, is a conversation between a young woman and a “Dude” at Bar Harbor, Maine, in which the woman finally rids herself of a pesky “Dude” by threatening to introduce him to her parents to arrange marriage.xlvii

An advertisement for his performance in “The Moonlight Marriage” at the Madison Square Theatre lists Mrs. August Belmont as a ticket agent and member of the Executive Committee organizing the benefit for the Home for the Destitute Blind. Ironically, her son, August Belmont, Jr., was a member of the Knickerbocker Club, the home of the original “Dudes” who were said to be Robert Sale Hill’s inspiration to coin the word in the first place.xlviii

The word “Dude,” which seems to be passing into the vernacular of the street, is an importation. An Englishman of athletic habits and stalwart frame, named Hill, after visiting the Knickerbocker Club lately, was so struck with the listless appearance of most of the members that he wrote to the World and classified them as “Dudes.”

“New York Gossip. The Genus “Dude” in All His Manifestations of Gorgeous Idiocy,” Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1883, page 9. (reprinted in The Shreveport Times, March 2, 1883).

Several months before the publication of Sale Hill’s original “Dude” poem, August Belmont, Jr. may have even helped introduce the fashions that would come to be known as “Dude” fashions. xlix

When I saw him [(August Belmont, Jr.)] he was coming around the corner of Twenty-eighth street into Fifth avenue, and the windows of the swell little Knickerbocker Club were alive with weak-looking faces, convulsively holding the single eye-glass, and gazing eagerly at the latest imported clothes.

Chicago Tribune, September 27, 1882, page 5.

In addition to acting, Robert Sale Hill recited poetry or read essays, sometimes with women acting out little vignettes illustrating the piece. At Lenox, for example, he staged a synchronized “fan drill,” in which “twelve young girls dressed in the costume of the period . . . danced a minuet and went through the exercises of the fan, in which they had been carefully drilled by Mr. Hill.” The performance was based on Addison’s comic essay, “the Use of the Fan” (1711), which represents a woman’s fan as her weapon, and imagines women drilled in its use, as soldiers are drilled in the use of firearms.

Women are armed with Fans as Men with swords, and sometimes do more Execution with them: To the End therefore that Ladies may be entire Mistresses of the Weapon which they bear, I have erected an Academy for the training up of young Women in the Exercise of the Fan, according to the most fashionable Airs and Motions that are now practiced at Court. The ladies who carry Fans under me are drawn up twice a Day in my great Hall, where they are instructed in the Use of their Arms, and exercised by the following Words of Command,

Handle your Fans,

Unfurl your Fans,

Discharge your Fans,

Ground your Fans,

Recover your Fans,

Flutter your Fans.

The Spectator, Number 102, June 27, 1711, reprinted in, The Spectator, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Donald F. Bond, Volume 1, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1965, page 495.

At the Madison Square Theatre, he appeared as the Prince, and Mrs. Potter as the Princess, in an adaptation of Tennyson’s poem, “The Princess.”l At Pittsfield, Massachusetts, he read Tennyson’s “A Dream of Fair Women,” in which, “as each are mentioned, lo! They appear, - in costume, in attitude, in expression, the heroines they represent. Helen of Troy, (Mrs. James Brown Potter); Iphigenia, (Miss Ada Smith); Cleopatra, (Miss Florida Yulee); Jeptha’s daughter, (Miss Lemist); Fair Rosamond, (Mrs. Frank Worth White); Joan of Arc, (Miss Lawrence); an exhibition of beauty, of costuming, of artistic realization of the characters presented such as Pittsfield never saw before . . . .”li

In October of 1886, Robert Sale Hill performed at Tuxedo Park during its first full season in operation. He performed “Good Night Babette,” one of Austic Dobson’s “Proverbs in Porcelain,” with Mrs. Frank W. White.lii Coincidentally, Mrs. Potter’s husband is widely believed to have introduced the first “Tuxedo” jacket at Tuxedo Park that same month (hence the name).liii Consequently, Robert Sale Hill may have been one of the first people in the United States to see a Tuxedo.

Although some of his amateur reviews were generally positive, one reviewer explained why he never had much success as a professional.

Mr. Robert Sale Hill has the same defect, combined with an indistinct utterance which is neither English nor American, and which, with the conventional restraints which hedge the amateur, make his lovemaking about as tender and impassioned as a clam’s.

The Sun (New York), April 20, 1884, page 6.

In a critique of amateur actors who want to turn professional, Robert Sale Hill was mentioned by name as an exception to the rule that such amateurs are generally insufferable.

Of all bores the amateur actor who is about to become a professional is the most pestiferous. Why it is that such a man cannot see that the fact of his going on the stage is not a matter of life and death importance to men who are so unfortunate as to know him. Capable and clever amateur actors like Mr. Robert C. Hilliard or Mr. R. S. Hill, who act as a diversion and who usually find something else to talk about than their histrionic experiences, are not open to the charges that are made against the majority of amateur actors.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 11, 1885, page 2.

Ironically, the one other amateur mentioned alongside his name in that article was a man named Robert C. Hilliard. Hilliard famously contended with Evander Berry Wall in a widely publicized battle for the title, “King of the Dudes.” The “battle,” such as it was, was fueled primarily by a newspaper writer named Blakely Hall who, like Hilliard, was from Brooklyn, with Hall acting essentially as a publicist for Hilliard who was then in the process of turning from amateur to professional. He also promoted Hilliard with a fake feud with Lilly Langtry and her boyfriend, Freddy Gebhard, in which she is said to have pushed Hilliard from the stage after he accused Gebhard of insulting his woman friends in a theater box.

The latest press dispatches bring glad assurance that Mr. Bob Hilliard has kindly consented not to spill Mr. Freddy Gebhard’s personal gore. . . . .

Mr. Hall has been working it very fine for the Brooklyn amateur actor of late. He has skillfully narrated the series of triumphs over Berry Wall which led to Mr. Hilliard’s recent coronation as King of the Dudes.

The Buffalo Express, November 19, 1887, page 4.

But whereas Bob Hilliard, as he became known, may have aspired to be a “Dude,” at least for promotional purposes, Robert Sale Hill was said to have been, “nothing of the dude.” The comments appeared not in a review of one of his plays, but in a report about one of his other passions – cricket, and also describes his success as a writer.

Mr. Robert Sale Hill, a handsome and manly young Englishman, who is also a fine cricketer and enjoys the game and all other athletic sports. Mr. Hill is a man of many accomplishments. Besides being a very clever actor, as all will acknowledge who have seen him play with Mrs. Potter and others, he wields a facile pen, has written some unusually good dramas, which it is to be wondered he has not acted in himself with Mrs. Potter, Mrs. Andrews, or some of the attractive amateurs. Mr. Hill also writes clever verses. I came across one on “Old Love-Letters” not long ago in a book of random poems, which ought to be republished. Possibly Mr. Hill does not realize how good his poems are. We are seldom fair critics of our own work. While a thorough gentleman, understanding these qualities to their fullest degree, he is nothing of the dude. These are the kind of Englishmen always welcome to our shores. Mr. Hill is the son of an officer of the English army long since dead, and the nephew [(actually first cousin)] of the Bishop of Sodor and Man in England.

Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1886, page 14.

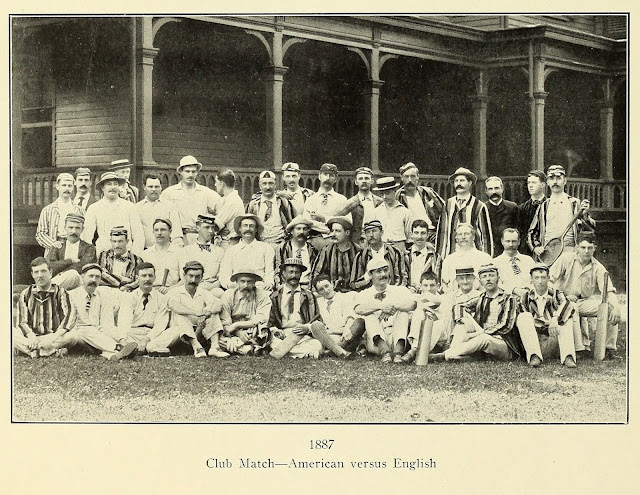

Robert Sale Hill was a very good amateur cricket player, at least by American standards; a leading member of the Staten Island Cricket Club of New York City.

Under the captaincies of E. J. Stevens, Robert Sale Hill and Cyril Wilson, the cricket record of the club has been most successful, and at present time there seems to be as strong material for the future welfare of the game as ever there was during any period of its existence.

“The Staten Island Cricket and Baseball Club,” Outing, Volume 11, Number 2, November 1887, page 104.

His name appears in box scores of cricket matches every year from 1882 through 1887, frequently as one of the top scorers on his team.

R. S. Hill treasurer of Staten Island Cricket Club, also lists his statistics. “Of those who played in a majority of the first eleven matches, E. Kessler leads with an average of 12-75, R. S. Hill being second with 8-11. In Second Eleven matches, R. S. Hill is third, with 7-66. In the first eleven bowling, E. Kessler took the lead with n average of five runs to a cricket; R. S. Hill third, with 7-50.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 19,. 1882, page 3.

The Staten Island Cricket Club hosted a team from England in 1885. Twenty years later, Robert Sale Hill would host an American team visiting England. But the photograph below is not from one of the England-versus-the-USA matches in 1885, but from a Fourth of July match two years later, between English and American members of the club – the “Staten Island annual match, Americans against English . . . a club match.”liv

|

Randolph St. George Walker, History of the Staten Island Cricket and Tennis Club, 1872-1917, New York, H. R. Elliot & Co., 1917, page 4. |

|

This detail from the above image may be

Robert Sale Hill, based on comparison with his photograph on the

frontispiece of his 1892 collection of poetry. |

Although there are few intimate details of his life in most of the references to Robert Sale Hill in print, some of his own writings may offer a glimpse or two into his personal life. His poem, “Old Love Letters,” for example, is written from the point of view of a young man in love with a woman whose parents opposed the relationship. He left her behind, “struggled in foreign countries” to “seek a fortune,” amassed an “ample fortune,” returned home “to claim my own,” but he “was too late” – she was dead.

Too late – a little black-edged letter,

Written and sealed with dying breath,

Contained these words, “I’ve loved you ever,

And have been faithful unto death.”

Her parents offered consolation,

Asked me to share with them my grief.

I fled their presence, with thanksgiving,

And sought in solitude relief.

Here in my chamber, with her letters,

A ribbon, and a lock of hair,

I speak with her, for she’s in heaven,

And heaven is reached by earnest prayer.

And now perhaps you think I’ll marry,

Forget the past, and happy be.

No; to her memory I’ll be faithful,

As unto death she was to me;

For well I know, although in heaven,

Where earthly ties all must forget,

She is so pure, God will forgive her,

If, robed in white, she loves me yet.

“Old Love Letters,” Robert Sale Hill, from the collection, Gus Williams, Fireside Recitations, New York, De Witt, 1881, page 60-63.

If the poem were autobiographical, it was not the only time he lost a loved one to an early death. His first wife died in 1891, at the age of 22.

Robert Sale Hill’s engagement to Sarah Randolph “Sadie” Foote was society news in New York City in 1886 – she was a grand-niece of the former Governor Randolph of New Jersey and daughter of a prominent Wall Street broker.

The engagement is announced from New York of Mr. Robert Sale Hill and Miss Sadie Foote, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Frederick w. Foote of 57 West Nineteenth street. Miss Foote was one of the debutantes of the past winter, and is a very attractive girl. Mr. Hill is one of the most popular amateur actors, and in fact is the jeune premiere of the New York amateur stage. The wedding will take place in November.

The Boston Globe, May 23, 1886, page 13.

Robert was more than twice her age when they married; he was thirty-six, she was seventeen – a difference of nineteen years.lv The age difference calls to mind another one of his poems, “The Rising Generation,” published in the humor magazine, Puck, in 1891. The poem is written as a conversation between a “Man of the World, aged about twenty five years” and a “Maiden, aged about ten years” – four years closer in age than Robert and Sarah. The young girl starts the conversation:

“If I were just as big as you,

And you were small like me,

If you were I, and I were you,

What would you like to be?

Would you care to be an angel,

With harp, and always good,

And practice music all day long –

As Aunt Kate says I should?

Or would you like to have a beau

Like Jack Jerome, next door;

He kissed me thirteen times last night,

And then he cried for more;

Or would you?”

“Wait one minute,

I’ll tell you what I’d do.

If you were just as big as I,

And I was small like you,

I would not care for Jack Jerome,

And music is a bore;

But when your mother kissed me,

You bet I’d ask for more.

Of course, you must not tell her this,

For such things can not be.”

“Well, if you like Mama so much,

Why don’t you wait for me?”

Robert Sale Hill.

Puck, Volume 29, Number 754, August 19, 1891, page 411.

Whereas Sarah Foote may have inspired his poetry, her father may have inspired his prose; a satirical how-to guide to investing, “How to Lose Money on Wall Street,” published in 1886.

Frederick W. Foote started his career as a clerk in the Sub-Treasure, under John J. Cisco, then the Assistant Treasurer of New York. Cisco invited Foote to join his firm, John J. Cisco & Son, bankers, first as manager and later as a partner.lvi Cisco had been at one time a government director and treasurer of the Union Pacific Railroad, and their firm was active in railroad stocks.lvii The town of Cisco, Texas is named for him (or the firm), as a result of his involvement in the Houston and Texas Central Railway. Presumably, Frederick W. Foote was talented and made a certain amount of money, but his career was not without some failures.

In 1883, Foote and 1,200 other stockholders (including, famously, Oscar Wilde) were victims of a famous, fraudulent investment scam, “Keely’s Motor,” a sort of perpetual motion machine, which attracted otherwise sensible investors – the Theranos swindle of its day. And within a year of the founder’s death in 1884, John J. Cisco & Son descended into insolvency. The troubles appear to have been caused in part by financial machinations by the railroad magnate, C. P. Huntington, and exacerbated by panic on the part of at least one investor.

This depreciation had been caused by the action of Mr. C. P. Huntington, who, having obtained control of the road, allowed a default on the January coupons of the first mortgage bonds, and then bought up the coupons through his Southern Development company. Mr. Dos Passos could suggest no explanation of Mr. Huntington’s course, except a desire to secure a lien on the road prior to the principal of the first mortgage bonds.

Wilkes Barre News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), January 17, 1885, page 3.

The newest and most startling phase in the failure of John J. Cisco & Son, the bankers who were thought to be founded upon a rock, and whose downfall created such an alarm in financial circles has been brought to light. . . .

. . . Mrs. Edward H. Greene, wife of the ex-President of the Louisville & Nashville, hastened the collapse. . . .

[An insider connected with the affairs of the firm told a reporter]: “Mrs. Green caused the suspension of the firm. She had banked with the firm for over twenty years and had used the firm in many ways. She was an old friend of John J.’s and thought the firm sounder than the Bank of England. Several days ago she heard, while temporarily stopping at Bellows Falls, Vt., the rumors affecting the firm’s credit. Her reason forsook her. She had $500,000 on deposit with the firm and in its vaults were $25,000,000 in Government, railway and other valuable securities. She immediately penned a note demanding that her balance of $500,000 be transferred to the Chemical and one or two other banks.”

Ottawa Weekly Republic, February 12, 1885, page 1 (from the New York Morning Journal).

Robert Sale Hill explained the purpose of his satirical guide to investing in the introduction.

I will undertake to solve the problem, which so many have fruitlessly attempted, namely: “How to make money on Wall street,” by first proving how easily it can be lost, and then leaving it to your own common sense to define the very best and only sure method left by which it can be made.

Robert Sale Hill, How to Lose Money on Wall Street, a Chapter on Wall Street in Four Parts and a Moral, by R. S. H., Author of “The Dude,” New York, G. W. Dillingham, 1887, page 5.

The book is laid out in four chapters, “Manipulation,” “Statistical Information,” “Sure Points,” and “Avarice and Obstinacy.” The chapter on manipulation appears to describe something similar to the methods Huntington used to devalue Cisco’s railroad stock before reacquiring it under another corporate entity.

Let us suppose that “A” owns numberless railroads and has millions at his command, while at the same time he has good grounds for believing a certain road has more brilliant prospects than the rest. Does he go directly to his friends, and those interested with him in his schemes, and say “the stock of this road is cheap, for the improvements I purpose making will greatly enhance its value?” Oh no – he first calculated what these improvements will cost, and then calls a meeting of the directors, when it is unanimously agreed that the road is not earning sufficient money to defray the suggested improvements, therefore it will be expedient to issue a new bond. This is accordingly done, and at the same time the cappers of the game, or shall we say the confidence men are instructed to belittle the property and talk vaguely of the possibilities of a receiver being appointed, &c. The result being that small holders hasten to sell their little holdings which the aforesaid pious directors quietly absorb, and having by this eminently square and honorable transaction, secured the widows mite, the honorable boar suddenly discover that the road is an invaluable adjunct to another road well and favorably known as a sure dividend payer, and hey presto the magician’s wand is waved again. The confidence men are once more called out, rumors of a great consolidation are bruited abroad a four per cent. dividend is almost assured the stock begins to jump, and the lambs, not already too closely shorn, begin to play around the resuscitated bauble, and rush in pell mell to secure the prize; the stock advances, the rumors spread, the public buy, the directors sell, and the bubble bursts, only to be again inflated, when a fresh lot of lambs are fat enough for the butcher’s knife, or shearer’s shears.

How to Lose Money on Wall Street, pages 7 and 8.

But he didn’t place all of the blame on Huntington. Sale Hill appears to pin some of the blame on his father-in-law.

[W]hen two years ago the president of one of New York’s oldest banks advanced the capital intrusted to his care, to promote schemes which promised fabulous returns, it would be paying a very poor compliment to his business education and sagacity to say that he was not perfectly well aware such results could not be attained by simple and honest business methods, nor can it be justly inferred that any individual who invested money on such terms, and with the hope of such results, was any less culpable, unless indeed, he was utterly ignorant of business.

How to Lose Money on Wall Street, page 8.

It’s not known how well the criticism went over at his in-laws’ house, but he and his wife left town the following year.

Robert Sale Hill disappeared from the society, entertainment and sports columns of New York City newspapers after 1887, only to reappear in the society, entertainment and sports columns of Helena, Montana, the following year.

Helena, Montana

In Helena, he resumed many of the activities he had pursued in New York City. He played cricket.

BEATEN BY HELENA.

The Butte Cricketers Get Laid Out by the Helena Boys.

The Butte cricketers have got home from Helena and report that while they had a nice time, they got badly beaten by the Helena eleven. . . .

The players were as follows: . . . Helena Team – R. S. Hill. . . .

In the second innings Helena scored 93. Hill (18), Nicholson (22), Stuggs (16) and Kane (10), batting in good form.

The Butte Daily Post (Butte, Montana), August 13, 1888, page 4.

He formed a literary society, and gave public readings of original poetry.

NEW LITERARY SOCIETY.

A society called the English-American Literary society were handsomely entertained by Dr. Leiser at his rooms in the opera house building, on Thursday evening. . . . Robert S. Hill recited finely an original poem, possessing much merit. . . . Those present were Gen. Greene and wife, Mr. and Mrs. Robert S. Hill . . . .

The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana), February 3, 1889, page 2.

He and his wife both acted in plays.

The Independent-Record (Helena), July 18, 1890, page 2.

He was elected President of a tennis club while producing an Opera.

Robert S. Hill has been elected to fill the vacancy as executive officer in the tennis club . . . Mr. Hill is to devote his energies to the east side ground, and it is to be hoped he will exert himself in the matter as soon as the “Erminie” rehearsals are over and not permit the grass to grow under his feet.

The Independent Record, April 21, 1889, page 2.

THE OPERA “ERMINIE.”

A Financial Success and the Promoters Pleasantly Remembered.

Financially the three performances of “Erminie” given by the Encore club were a success . . . . To Mr. R. S. Hill, a valuable and handsome carving set with solid embossed silver handles.

The Independent-Record, May 22, 1889, page 4.

He was a charter member and first Secretary of the Helena Athletic Association and helped organize a new baseball team.

. . . The following officers were then unanimously elected: . . . Secretary – R. Sale Hill.

The Independent-Record, April 12, 1890, page 5.

And he adopted the customs of his new country, volunteering for the decorations committee for Helena’s Fourth of July celebrations.

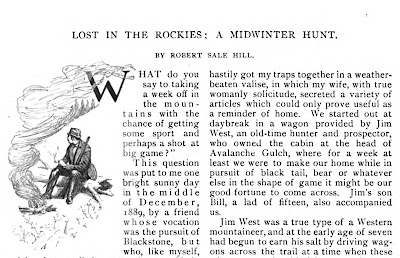

His new surroundings also gave him something new to write about. Outing magazine published two of his stories about hunting in the Rocky Mountains. In “Lost in the Rockies; A Midwinter Hunt” (January 1891), he gets separated from his hunting party and lost in a snow storm. With the light fading and temperature dropping, he stumbles across an abandoned cabin. He spends a cold, wet night in a drafty cabin and makes his way back to his friends the next morning. His account of the reunion suggests he was a religious man.

Our meeting was a strange one; little was said, but the tones of Harley’s voice as he said, “Thank God, old man, we have found you alive.” Still ring in my ears, and the grip of Jim’s hand spoke volumes. A drink of whiskey and a sandwich revived me greatly, and I was able to tell them my experience as we made our way back to Jim’s hut; Jim said that in all his wanderings he had never even guessed as to the existence of such a cabin, while Harley simply then remarked it was providential; but when we got back to Jim’s cabin, and while he was preparing me something to eat, Harley, his voice breaking with emotion, told me of a sleepless night spent in prayer to the only Power that could save me, and in this grand belief he had grounded his faith. Jim had given me up, for, as he said, no mortal power could save a man who was lost in the Rockies on such a night.

“Lost in the Rockies; A Midwinter Hunt,” Robert Sale Hill, Outing, Volume 7, Number 4, January 1891, page, 277.

In “Rocky Mountain Echoes,” his hunting partner misses their only shot at a big horn sheep when a boulder slipped out from under his feet as he was taking aim. Their Swedish guide, Ole, got off a shot, so it wasn’t a complete loss, but they were disappointed that they weren’t able to get their own.

Had the unfortunate boulder not given way we would have had a fair chance to show our skill, but as it was we were compelled to be content with the result of Ole’s fine ram. . . .

Next day we made another attempt and failed to locate game. Mountain sheep are too wary to allow novices to redeem mistakes. Eternal vigilance is their motto when once the tell-tale bark of the Winchester has stirred the tongues of Rocky Mountain echoes.

“Rocky Mountain Echoes,” Robert Sale Hill, Outing, Volume 26, Number 6, September 1895, page 452.

When he wasn’t writing, performing or playing, he had a job with the Federal government, as a “deposit clerk” at the United States Assay Office. The United States government’s assay officer received “gold and silver bullion, for melting and assaying, to be returned to depositors of the same, in bars, with the weight and fineness stamped thereon.”lviii

U.S. Assay Office, Helena, Montana. Helena Montana, None. [Between 1875 and 1900?] Photograph. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006676354/.

Helena, Montana was located in an important mining region, and its assay office was one of only six in the country at the time. So if you see an old western film in which bad guys rob a train or stagecoach loaded with gold or silver bars, it’s not unreasonable to imagine that those bars (or the gold or silver in the bars) could have passed through the hands of the person who coined the word “Dude.”

One of his bosses at the assay office was a man named M. A. Meyendorff.lix Meyendorff is variously described as the “Superintendent” or the “Melter” at the assay office. The position of “Melter” was one of two jobs, in addition to “Assayer,” that were subject to Presidential appointment and the advice and consent of the Senate. Meyendorff had high-placed political connections in the United States and came from a family with a history in Europe that rivaled the Sales and the Hills for titles and notoriety.

Michael Alexander Meyendorff, or “Count” Meyendorff as he was locally known, was born in Poland in 1848 to a family with a long line of actual Barons and Counts.lx The Meyendorff family is said to have been made Swedish Barons in the 17th Century. In the mid-Nineteenth Century, there were several titled Meyendorffs. A Baron Alexander von Meyendorff was a respected geologist. Baron Felix Meyendorff served the Emperor of Russia as the Ambassador to the Vatican.lxi A Baron Peter von Meyendorff was at one time the Russian Ambassador to Austria-Hungary.lxii And Franz Liszt exchanged letters with a Baroness Olga von Meyendorff.lxiii

Baron Felix von Meyendorff famously insulted the Pope, resulting in Russia and the Vatican severing diplomatic ties. The dispute started with the Pope criticizing Russia for treating Roman Catholic clergy in Poland poorly. Count Meyendorff responded, insisting that the Emperor of Russia only treated them poorly because they were armed agents of the resistance, not for any theological grounds, which resulted in the Pope issuing a declaration ordering the Polish people to submit to Russian rule, and for the Roman Catholic clergy to stay out of politics.lxiv

The disagreement escalated two years later when Meyendorff accused several Polish Bishops of being revolutionaries. He topped it off by telling the Pope, face-to-face, that “Poland, Catholicism, and revolution are one sole and indivisible trinity,” prompting the severing of diplomatic relations.lxv

It’s not clear where on the family tree Michael Alexander Meyendorff of Helena, Montana fell, or whether he was actually entitled to a title, but he was not on the same side, politically, as his Russian diplomat relatives. Meyendorff was expelled from school at the age of thirteen for rebelling against Russian rule of Poland. He joined the Revolutionists in 1863, participating in two battles against the Russians. He was caught and spent eight months in prison, before being sent into exile in Siberia. His brother was taken from his bed and executed without a trial.

Meyendorff had a half-brother, Colonel Julian Allenlxvi (perhaps changed from Alliwiskilxvii ), who helped organize a Polish Regiment in New York at the beginning of the Civil War,lxviii and was later on General Sherman’s staff. He brought his brother’s case to the attention of Abraham Lincoln, who started the diplomatic ball rolling. After Lincoln’s death, the American Ambassador to Russia, Cassius M. Clay, fought for his release. Eventually his sentence was changed from exile in Siberia to exile in the United States.

Having escaped war, execution and exile, M. A. Meyendorff lived a much more peaceful existence in the United States. He arrived in the United States in 1866 as (what he described as) a “ward of the government.” He enrolled in the University of Michigan and graduated with a degree in Civil Engineering in 1870.

After college, he took jobs building railroads, first in St. Louis, and later with the Northern Pacific, which landed him in Helena, Montana in 1873. He moved back east for medical treatment after breaking a hip, and wound up working for the Department of the Interior in Washington DC in 1875. He eventually moved to St. Louis to open the United States Assay Officer there, later transferring back to Helena, Montana where he had once built railroads. In 1884, Meyendorff went on the campaign trail to stump for the Republican Presidential Candidate, James G. Blaine, frequently speaking to Polish groups.

In early 1891, Robert Sale Hill’s wife, Sarah, served punch at a social function in Helena.

Mrs. Phelps gave an elegant reception on Thursday afternoon in honor of her guest, Miss Taylor. . . . A number of ladies assisted Mrs. Phelps. . . . Mrs. Robert Sale Hill served a tempting beverage from a magnificent bowl, in the hall. . . .

The young ladies seen flitting here and there served in their most charming manner.

. . . Mrs. Hill, terra cotta velvet and pale turquoise blue China silk.

The Helena Independent, February 1, 1891, page 3.

Mrs. Phelps’ fancy party was Mrs. Sale Hill’s last hurrah in Helena. In the next newspaper column over from the article about the party was a notice about their plans to leave the city.

It is regretted that Mr. Robert Sale Hill and family are to move to Tacoma. Mr. Hill’s stories, which have been complimentarily noticed both here and in England, were becoming a source of pride to Montana. It is to be hoped that he has become so thoroughly imbued with the spirit of the Rockies that he will not soon forget them.

The Helena Independent, February 1, 1891, page 3.

It may also have been her last hurrah – ever. She died in May of 1891, leaving him with a three year old son to care for alone. The circumstances and cause of death are unknown, but she is buried with two sisters in a Foote family plot in Morris County, New Jersey. lxix

He married again, likely after he moved to Tacoma in early 1891, and before June 1892, when “Mrs. R. S. Hill” attended a “pleasant tennis tea” a tennis club in Tacoma.lxx His new bride was not someone he met out West, but an old flame to whom he had once been engaged.

A cryptic comment in a report of his marriage to Sarah Randolph Foote hints at the existence of the previous relationship. Someone attending the wedding commented that this time he had “actually married,” suggesting that it was not his first flirtation with marriage.

Mr. Robert Sale Hill, well known and much admired as an amateur actor, was also married on Thursday to Miss Sara Foote – “actually married,” as a young lady pensively remarked when she reached the door of the church – from which it may be inferred that the bridegroom had contemplated matrimony on previous occasions and from a different standpoint. Mr. Hill is an Englishman and a grandson of Sir Robert Sale of the British army, who distinguished himself in India.

The Sun (New York), November 14, 1886, page 8.

The comment is likely a reference to his engagement, three years earlier, to Miss Helen Harrison of Baltimore.

The engagement of Mr. Robert Sale Hill, a grandson of the late Sir Robert Sale of the British army, to Miss Helen Harrison of Baltimore, is confirmed.

The Sun (New York), November 11, 1883, page 5.

The engagement may have been “confirmed,” but the wedding was not; it would have to wait until after the untimely death of his first wife in 1891. Their ultimate reconciliation so quickly after the death of his first wife suggests that whatever the original, underlying cause of their break-up, they had parted on friendly terms. And although no one recorded the reasons for the break-up, reports of family trouble in Baltimore after their engagement suggest external factors unrelated to their personal relationship may have played a role.

Helen’s mother died in January 1885, leaving her nearly-seventy year old father, George Law Harrison, with a minor son at home to care for.lxxi Helen, then twenty-nine, was the oldest of four surviving children with his second wife, Helen Troup Davidge. Her sister Margaret had a two-year old at home, and her sister Henrietta was not quite twenty. Her brother George Law Harrison, Jr. (the first boy after eight girls with two wives) was thirteen years old. It is possible that she took over the caretaker role of her mother after her death, which may have put a crimp in her own romantic relationship.

Things took a turn for the worse when her father died nine months later. Her brother came under the jurisdiction of the Orphans’ Court,lxxii and she was named guardian. lxxiii She remained in that role until at least May 1891, when he was twenty years old.lxxiv He would have reached the age of majority by 1892, freeing her to marry her ex-fiancé, now a widower with a three year-old son.

His wife’s death was not the only tragedy Robert dealt with in Helena. In 1890, he was one of the last people to speak a friend before his suicide, and first person called to the scene after he shot himself in what may have been just minutes later.

After supper on May 16, 1890, a Helena attorney named Edward F. Crosby went to Robert Sale Hill’s home at 723 Spruce Street (since been renamed Holter Streetlxxv), chatted “in a pleasant way” for a few minutes, borrowed some papers and a novel, and went home.

There is no definite knowledge as to what occurred from that time until the fatal shot was fired. Through a friend Mrs. Crosby stated that her husband came into her room, bade her good night and then went to his room across the hall in the second story of the house. A few minutes later she heard the shot and rushing into her husband’s room saw him lying on the floor. Hastily donning a wrapper, she went down to Mr. Hill’s residence and told him what had happened. Mr. Hill came immediately back to the room where Crosby was lying dead. . . . A bullet hole was through his breast and near the bed was an American double action bulldog revolver of 44 calibre. An open drawer in the washstand indicated that the weapon had been hastily taken from its place.

The Independent-Record, May 17, 1890, page 1.

The revolver may have been “hastily” taken from the drawer, but the act may have been planned in advance.

The will of Edward F. Crosby, nephew of ex-Governor Crosby, who committed suicide May 16, has been filed for probate. It disposes of $200,000. It throws some light upon the cause of Crosby’s suicide. After giving all his property to his infant daughter, he says the reason for leaving his property to his daughter was because his wife hated him.

The Buffalo Commercial (Buffalo, New York), June 2, 1890, page 1.

But his wife was not left empty-handed. His life insurance company made a public showing of ignoring the no-suicide clause of its policy, and paid the $10,000 policy in full. Never let it be said that insurance companies don’t have a heart . . . . .

Dear Sir – . . .

It is a cardinal principle of the management of this Society, that no advantage shall ever be taken of technical rights when the equities would require the opposite course.

Acting upon this principle, we cheerfully comply with your request, and have to-day instructed our manager at Helena, Mr. T. H. Burke, to take the necessary steps for the payment of the policies on the life of Mr. Crosby.

The Independent-Record, June 25, 1890, page 1.

Edward F. Crosby arrived in Montana in 1883 from the East Coast, likely New York City. His father lived on Broadway in New York City, and he and his wife visited Staten Island in 1889, so it is possible that he had an acquaintance with Sale Hill before he arrived. It’s also possible that they merely struck up a new friendship based on mutual interests.

Like Robert Sale Hill, Crosby was a man of letters. In addition to his job as an attorney and real-estate investments, he worked for “Eastern magazines and newspapers,” even while living in Helena. It’s not clear in what capacity he worked for newspapers, but he did write at least one story published in a newspaper in Helena in 1883. It was a Faustian tale entitled, “The Voice,”lxxvi in which the narrator is tormented by a voice from a floating, disembodied head of a Satyr, which promises him “fame, wealth, power, and . . . the added inducement of love,” if he would kill his father. He does so, only to have the voice torment him with guilt after the fact. He lands in jail, becomes critically ill, and looks forward to his own death.

Impelled by the voice, I unconsciously found myself at the door of my father’s room. A red mist seemed to come over my eyes. I heard the voice saying:

“Gold, love, power.”

I remember striking violently with something I had in my hand. Then I have a dim recollection of kneeling at the side of the sofa, beside my father’s form (strange that he did not move or utter a cry) and holding a vial to catch the blood that was gushing from his side.

It was done.!

. . . . The face has never left me. Often have I tried to strangle it – to stop the accursed voice that has never ceased to cry, “Murderer! Patricide!” and to paint the tortures of the damned to me.

I am getting weaker; my life is drawing to a close. Oh, for oblivion! For rest from my fate! I defy your gibbering voice. I defy your distorted face. In death I defy you.

“The Voice,” Edward F. Crosby, Helena Weekly Herald, March 8, 1883, page 1.

Robert Sale Hill was in Tacoma by May of 1891. One of the first references to his life in Tacoma ties him to a real estate investment in Montana. An advertisement for land sold by the Castle Land Company in May of 1891 lists “Robert Sale Hill, Broker, Tacoma, Wash.” as a purchaser. The town of Castle is now a ghost town famous for its once being the home of Calamity Jane, who opened a restaurant there with her husband in the early 1890s.lxxvii It’s intriguing to imagine that the originator of the word “Dude” could have sat down for lunch at Calamity Jane’s restaurant while scouting out, or looking after, his plots of land.

Tacoma, Washington

In Tacoma, Robert Sale Hill resumed his familiar lifestyle, joining the Tacoma Athletic Association,lxxviii playing tennis, publishing poetry and hunting stories, and acting in amateur theatrical productions for charity.

He lived in Tacoma when he privately published a collection of his poetry. The frontispiece of the book has a photograph of him with his son, Robert Sale Hill, Jr., and the book was dedicated to his late wife.

This little volume I dedicate to the memory of a true, brave, and sympathetic little wife, who shared all my sorrows and troubles, bearing up bravely to the end. Whatever intrinsic worth there may be in my later poems is due largely to her warm and sympathetic interest, ever ready to be manifested in my life’s efforts.

Robert Sale Hill

Robert Sale Hill, Serious Thoughts and Idle Moments, Privately Printed, Cambridge, England, University Press: John Wilson and Son, 1892.

He was also involved in some capacity with the Tacoma & Steilacoom Railway Co.,lxxix and was named the Vice President and General Manager of the Commercial Electric Light and Power Company.lxxx The two projects may have been related, as the Tacoma & Steilacoom was an electric railroad.lxxxi

The Commercial Electric Light and Power Company ran into difficulty as a result of a misunderstanding over fuel for the plant. They arranged for a mill company to take half the stock in the company, in exchange for building a power plant on the mill grounds. As part of the agreement, the Power Company believed they were to receive free fuel from the mill, whereas the mill surprised them with a bill.

In the aftermath of the dispute, the city issued a public letter directed personally Robert Sale, demanding that his company remove their transmission wires from city-owned poles.

Electric Light War.

Tacoma, Oct. 9. – A war between the city and the Commercial Light and Power company is on and from the enthusiastic manner in which the managers of the city’s fight have entered upon the campaign it would seem that the fight is on to stay. . . .

Robert Sale Hill, general manager of the Commercial Light & Power Company. – Dear Sir: You are hereby notified to remove all wires belonging to your company from the poles owned by the city of Tacoma before October 25th.

The Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), October 9, 1893, page 1.

His company was essentially dissolved by 1895.

|

Los Angeles Herald, January 2, 1895, page 2. |

Hong Kong

The failure of his business venture may have prompted him to seek greener pastures again. The family left Tacoma in 1895 for Hong Kong, where he had been offered a position as a customs clerk.

Mr. and Mrs. Robert Sale Hill are to make their home in China, Mr. Hill having connected himself with the Hongkong customs.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 21, 1895, page 10.

They actually did make the trip,lxxxii but did not stay long. They were in England by 1898, where they would remain.

Miss Mattie Baker will sail from England on Monday for New York. While in London Miss Baker was the guest of Mrs. Robert Sale Hill, who formerly lived in Tacoma.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 22, 1898.

London

In London, Robert Sale Hill lived a few blocks from Buckingham Palace, at 70 Victoria Street S.W. His name and address in London were listed in the Royal Red Book, the Royal Blue Book and (surprisingly) the New York Social Register. lxxxiii He worked at Brown, Shipley & Co., at 123 Pall Mall.

The London Office of Brown, Shipley & Co., 123 Pall Mall. John Crosby Brown, A Hundred Years of Merchant Banking, a History of Brown Brothers and Company, New York, private printing, 1909.

Brown, Shipley & Co. was the London branch of Brown Brothers & Co., the American bank, coincidentally (or not?) connected to the family of his one-time acting partner, Cora Urquhart Potter. A comment in a history of the bank describes the position he held.

Mention should also be made of H. J. Metcalfe, who looked after the Travelling Credit Department in Founders’ Court for many years during the summer months, from 1865 to 1893. He was succeeded by Robert Sale Hill, who is now in the Pall Mall office.

John Crosby Brown, A Hundred Years of Merchant Banking, a History of Brown Brothers and Company, New York, private printing, 1909, page 164.

In 1907, when a record number of American tourists spent a record amount of money in England, Robert Sale Hill was interviewed for his take on the invasion.

[By Cable to the Chicago Tribune.] [Copyright: 1908: By the New York Times.]

London, Aug. 31. – To all appearances there are as many American tourists in London as ever. . . . The amount of money the invaders left behind them also is unprecedented. As to how much this is, the estimates vary from $75,000,000 to $100,000,000. . . .

Robert Sale of the Brown-Shipley company, a banking firm which carries a large proportion of American accounts in London, also is terrified at the enormous sum spent in England in a season by Americans.

“While I believe $100,000,000 to be a fair approximation of the amount of credits carried here by American visitors, I don’t think the actual expenditures surpass $75,000,000,” he said. “The day is past when the traveling American spends the entire letter of credit. In a hurry he cables home for more. He doesn’t squander money now as he did, say, five years ago. Then everything seemed cheap to him and he spent money right and left. Now he has become experienced. Moreover, prices have gone up.

“Our traveler pays and expects to get his money’s worth. He treats a letter of credit as he would a bank account at home and often takes a portion of it back with him to the states. The amount spent here this year unquestionably is greater than ever before.”

Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1907, page 6.lxxxiv

In addition to hosting American friends from Tacoma, the Sale Hills entertained travelling American cricket clubs and American diplomats and military personnel.

Thanks to the good offices of Robert Sale Hill, who for many years was identified with the defunct Staten Island Cricket Club, the courtesies of the United Arts Club in St. James Street have been extended to members of the Philadelphia cricket team now in England.

The New York Times, July 12, 1908, page 25.

Commander Edward Simpson, naval attaché to the United States Embassy at London, and Mrs. Simpson, formerly of Washington and Baltimore, gave their first dinner party in their official capacity last week at the Hotel Ritz. . . . [T]he guests included . . . Mr. and Mrs. Robert Sale Hill, the latter formerly Miss Harrison, of Baltimore; . . . the American Ambassador and Mrs. Whitelaw Reid . . .; Admiral Sir Edmund Fremantle and Lady Fremantle, Lieut. Commander Chester Wells, U. S. N., and . . . Capt. Sydney A. Cloman, military attaché of the embassy. . . .

The Washington Herald (Washington DC), July 27, 1909, page 5.

And Americans visiting London entertained him. An item in the New York Times noted that two visiting Americans had generously offered their yachts for his use during his summer vacation in 1909.

The New York Times, July 4, 1909, page 21 (continued on page 22).

Robert Sale Hill has gone to Bournemouth for a two weeks’ holiday. Duncan Ellsworth and G. Louis Bossevain have both offered him the use of their yachts.

The New York Times, July 4, 1909, page 22.

Robert Sale Hill left Brown, Shipley & Co. in 1910, to join the London offices of Harris, Winthrop & Co., a relatively new American investment firm.

Robert Sale Hill, who is very well known to many traveling Americans through his long connection with the banking firm of Brown, Shipley & Co., has also joined Harris, Winthrop & Co.

Commercial West, Volume 17, April 2, 1910, page 13.

Harris, Winthrop & Co. was formed in 1906, when Henry Rogers Winthrop, the treasurer of the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States, resigned to form a partnership with the firm, J. F. Harris & Co., of Chicago.lxxxv

The Times (London), May 13, 1910, page 13.

The firm had offices in New York, Chicago, London and Paris, offering access to American markets through most of the major US stock and commodities exchanges.

Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1912, page 20.

Harris, Winthrop & Co.

STOCKS, BONDS, GRAIN,

PROVISIONS, COTTON, COFFEE

Members: New York Stock Exchange, New York Cotton Exchange, New York Coffee Exchange, Chicago Board of Trade, Chicago Stock Exchange, New York Produce Exchange, Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce.

Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1912, page 20.

Jersey

Robert Sale Hill died on the Island of Jersey in 1922.

Baltimore Sun, April 21, 1922, page 17.

ROBERT SALE HILL

Notice of the death of Robert Sale-Hill, 67 years old, on the Island of Jersey, England, about April 7, was received Thursday by Mrs. Mordecai D. Tyson, 909 Cathedral street, in a letter from her sister, Mrs. Robert Sale-Hill, widow of the deceased. Since their marriage at Old St. Paul’s Church 25 years ago, Mr. and Mrs. Sale-Hill (nee Helen T. Harrison) have been living in England. Mrs. Sale-Hill is a sister of Mrs. Thomas M. Dobbin, Mrs. Henry Rowland and Mrs. Tyson, all of this city.

Baltimore Sun, April 22, 1922, page 13.

i Timothy Belmont, “The Hill Baronets,” LordBelmontinNorthernIreland.blogspot.com, May 22, 2020. https://lordbelmontinnorthernireland.blogspot.com/2014/05/the-hill-baronets.html (accessed May 17, 2021); Joseph Foster, The Baronetage and Knightage, Westminster, Nichols and Sons, 1881, page 312.

ii Apparently first published in the weekly magazine, America, it was reprinted in numerous newspapers and appeared in his self-published collection of poetry, Serious Thoughts and Idle Moments (1892).

iii Freeman’s Journal (Dublin), April 26, 1842, page 4.

iv The Hampshire Advertiser (Southampton, England), February 25, 1843, page 2.

v “Battle of Kabul and the retreat to Gandamak,” BritishBattles.com (https://www.britishbattles.com/first-afghan-war/battle-of-kabul-and-the-retreat-to-gandamak/) accessed May 14, 2021.

vi St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 1, 1880, page 4.

vii Sir Vincent Eyre, The Military Operations at Cabul, Which Ended in the Retreat and Destruction of the British Army, January 1842, With a Journal of Imprisonment in Affghanistan, London, J. Murray, 1843.

viii The Star of Freedom (Leeds, England), October 22, 1842, page 26.

ix The Morning Post (London), December 22, 1842, page 1.