Car wash culture arguably reached its apotheosis with the 1976 release of the classic film, Car Wash, and its soundtrack album featuring Rose Royce’s funk classic, Car Wash. The film portrayed a day in the life of the “Dee-Luxe Car Wash” in Beverly Hills, as its owner, workers and customers, deal with a bomb plot, communists, an audition, a radio contest and an attempted robbery.

The history of the car wash features equally colorful characters as advances in technology and new business models helped create the industry that one day would inspire those artistic successes many decades later. And many significant events in car wash history, appropriately enough, took place Beverly Hills-adjacent, in and around Hollywood.

The inventors, investors and entrepreneurs who built the car wash industry include crop sprayers, tour operators, horse-and-buggy livery stable operators, a successful lumber executive who lost a fortune in the ice cream and candy business, a Hollywood cameraman, director and movie star, a former Mayor of San Diego, two people with two degrees of separation from President Ulysses S. Grant, the national director of the Loyal Order of the Moose, and a man who developed amphibious landing tanks used in World War II.

The advances that drove the growth of the business include three major milestones; the assembly line-style, multi-station car wash (1912), the “semi-automatic” conveyor car wash (1926), and the “fully-automatic” all-in-one car wash with automatic conveyor, sprayer, scrubber and drier (1946).

The oldest known, purpose-built, multi-station assembly line car wash appears to have been built in Portland, Oregon in late-1911, and opened on New Year’s Day 1912. It may have been the first one ever built, although the people who built it did not seem to be sure. Early accounts claimed merely that it was the “first time a concern of this kind has ever attempted to operate on the Pacific coast.” But it was opened more than a year before the one that generally receives credit as being first, and no one has come up with evidence that one existed elsewhere before 1911.

Car wash historians, however, generally credit Frank McCormick and J. W. Hinkle with opening the first car wash in Detroit, Michigan in 1914.i Contemporary news accounts, however reveal that their Detroit car wash opened in 1913, one year earlier than generally reported, but more than a year after one had already opened in Portland. And although contemporary news accounts cited Frank McCormick’s name in association with the early Detroit car wash, J. W. Hinkle’s connection to the business (if any) is unclear.ii

All signs to point to Portland as the home of the original (or at least earliest known) “car wash,” and to Detroit directly copying its business model, not merely coming up with the same idea around the same time. When it opened in 1913, descriptions of Detroit’s car wash were nearly identical to those of one that had opened in Portland a year earlier. Some early reports of Detroit’s first car wash even refer to it as “following the lead of a Pacific coast concern.” And it adopted the same name, “Automobile Laundry,” and slogan, “Everything back but the dirt,” as the one in Portland.

The first “semi-automatic” car washes, in which conveyor systems tow cars through the successive car wash stations, were developed in Los Angeles in 1925 and in operation there by 1926. They were the brainchild of the former mayor of San Diego and a tour bus operator from San Diego’s U. S. Grant Hotel, and incorporated spraying technology developed by crop-sprayer manufacturers.

The first “automatic” car wash, in which a car is automatically towed, scrubbed and dried, all by machine without human hands, opened in Detroit in 1946. Its inventor would win a Horatio Alger award in 1950, the same year as Conrad Hilton (Hilton Hotels) and Charles Revson (Revlon Cosmetics).

And before and between the major car wash milestones, the car wash business was not stagnant. Many inventors and entrepreneurs continued to innovate car wash technology and business models, laying the groundwork for the kinds of car washes celebrated decades later in Rose Royce’s Car Wash.

Wash Racks

Before there were “car washes,” as such, there were “wash racks.” For many, if not most people (then and now), washing one’s wagon or carriage involved simply getting water, soap and a sponge, and washing it where it stood. The problem with doing that, however, was in many cases the lack of drainage created wet, unsanitary conditions. The solution was the “wash rack.”

But in the late 1800s, as awareness of the importance of public hygiene grew, and public sewer drainage systems became more commonplace, people started constructing facilities, frequently not much larger than a car, carriage or wagon, with slats or a “rack” above a concrete collection basin connected to a drainage system. Wash racks were installed in private and public horse stables, and later in automobile garages.

|

| Sacramento Bee, August 11, 1877, page 2. |

Evening Bulletin (Honolulu, Hawaii), November 1, 1900, page 1.

As automobiles became more commonplace, old “wash racks” were put to new use as a place to wash cars, and people also started building car wash facilities on the old model, as “wash racks” for automobiles. Wealthy owners built them into their garages, and garage owners and automobile dealers built them into their garages, workshops and showrooms. The availability of a “wash rack” was a selling point to attract customers, and an added service to provide another source of income.

The Des Moines, Iowa, Automobile Company has tendered members of the several automobile parties in Des Moines the use of a portion of its new building . . . for club purposes, and for a place of safe keeping for their machines. The place designed is 50x44 feet, and will be fitted with necessary power machines for the automobiles, a wash rack, and lockers for members of the club.

Automobile Topics, Volume 4, Number 12, July 5, 1902, page 544.

Plans are being prepared for Lee A. Phillips for an elaborate auto stable on the Spanish style. The stable will have a capacity for three machines, including tool room, robe room, lockers, wash rack and a charging set.

Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (California), March 15, 1904, page 4.

The East Side Auto Station, 200 Meeting street, Providence, R. I., occupies a two story brick building containing 12,000 square feet. The floor on the street level is of concrete, and, with the exception of a small office and the wash rack, is used exclusively for the storing of cars . . . . For transients a nightly rate for storage, washing, etc. is &1.25 for small cars, and $1.75 for large cars. Nightly storage not including washing, etc., is 50 and 75 cents.

The Horseless Age, Volume 17, Number 22, May 30, 1906, page 785.

|

Buffalo News, may 16, 1907, page 14. |

At the time, driving was different (specialized knowledge), cars were different (generally uncovered), roads were different (generally unpaved), and homes were different (generally no garage). An article from an automotive magazine about the business of operating a storage garage illustrates some of those differences, and stresses the importance of providing a wash rack for clients.

The dearth of space in which to store machines has led the majority of car owners to depend on the garage, and this is causing an increasing number of garages to spring into existence. Most of the automobile agents in large cities maintain a garage in connection with their salesrooms, and some have a livery feature added to this branch of the business. Apart from the agencies, however, in cities and towns garages are constantly being established which are owned and maintained by men not interested in the sale of automobiles.

The first essential for a successful garage is plenty of room. . . . Next to plenty of room the requirement of most importance is a wash rack. An automobile has to be washed every day when it is used regularly, and among most dealers the belief prevails that the average machine is damaged more in the wash room than it is on the road.

As a rule, the man who attends to the washing knows little or nothing about starting or stopping an automobile engine, and in nice cases out of ten, according to the dealers, he will collide with a post or one of the walls two or three times before the machine is safely on the wash rack. Some dealers, to avoid this difficulty, have had the whole of the floor space in their garage converted into a water-tight surface so that the machines may be washed without moving them. The Chicago proprietor of what is claimed as the largest garage n the world has this arrangement, and he says it is a big improvement over the old method.

Automobile Dealer and Repairer, Volume 3, Number 6, August 1907, page 199.

In Texas, where every thing is big, they installed what they claimed was one of the first large-scale wash racks in a public storage garage, after one in Chicago.

One feature that will be entirely distinct and new in Texas will be the wash racks. Two wash racks will extend the full length of the building. The cars will be ranged in four rows, with a wash rack between each double row. This will make it possible to wash and clean the cars without the necessity of moving them from place to place, and so avoiding all chance of accidents such as breaking lamps and fenders.

Only one other garage in the country has this feature, and that is a new garage just completed in Chicago.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 28, 1909, Sports Section, page 2.

The first large automobile garage in Billings, Montana was equipped with a “commodious wash rack.”

The Public Motor garage . . . is supplied with a commodious wash rack; repair department; stock room supplied with a large stock of accessories, carrying especially a large number of the best makes of tires of all sizes.

The Billings Gazette (Montana), August 8, 1909, page 9.

One popular style of wash rack was a combined turn-table/wash rack, which were installed in commercial establishments and private homes.iii

The back sixty feet of the lower floor will be used for a public garage. He will have a capable man in charge and it will be equipped with the latest machinery. He is having built now a turn-table and wash rack. by the use of this turn-table he will be able to store five or six autos instead of two.

Olathe News (Olathe, Kansas), September 15, 1910, page 3.

The Ernst Automobile Turn-Table and Wash-Rack

Western Architect, Volume 15, Number 4, April 1910, page 17.

The “Ernst” revolves with such ease that a Child can turn the heaviest car. The Ernst Combined Auto Turn Table and Wash Rack.

Club Journal of the Automobile Club of America, Volume 5, Number 1, April 12, 1913, page 24.

One element still common in do-it-yourself car washes was invented during the 19th century - the swiveling, overhead hose attachment, which allows the hose or cleaning attachment to move easily around the automobile. Patrick Ryan and Thomas Long patented one such swivel-hose attachment in a patent issued from an application filed in 1899.

Several models were available from different makers several years later.

Automobile Dealer and Repairer, Volume 3, Number 5, July 1907, page 175.

Automobile Dealer and Repairer, Volume 3, Number 5, July 1907, page 167.

As the second decade of the new century started, cars were generally washed standing in one place, on a wash rack, at home or in a garages. With more and more cars on the road every year, the time was ripe for something new.

The Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), December 31, 1911, section 4, page 10.

Portland

As 1911 came to a close, Portland, Oregon proved its “up-to-datedness” with what may have been the first-ever, purpose-built, systematic car wash facility, or (as it was then known) “Auto Laundry.”

Further proof of Portland’s up-to-dateness, and especially in the automobile line, is shown by the floor plan of the new automobile laundry that will open for business at Twenty-first and Washington streets, January 1.

The management of the new Hi Lung Changiv establishment will be in the hands of H. T. Barnhart, who will see to it that when a patron sends his automobile through the house that will be known by the slogan, “Everything Back But the Dirt,” that he will get value received and that the machine will come from the wash and drying rooms looking as near like a new car as it will be possible to make it look with the latest cleaning and drying improvements.

The name automobile laundry has been copyrighted, and means just what the words imply. You will be able to send your machine in one door in as dirty a condition as you care to let the machine get, and in the course of 20 or 30 minutes it will come at the other side of the house, washed, dried and polished. . . .

This is the first time a concern of this kind has ever attempted to operate on the Pacific coast, and Portland should lend her aid to establishing a new industry that will mean much to the automobile enthusiast. The company backing this concern has gone to the expense of putting up a substantial concrete structure 60x125 feet, and have fitted it up for taking care of cars as promptly as good treatment will permit.

The Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), December 31, 1911, section 4, page 7.

During its first week the “Auto Laundry” appears to have made a big splash.

H. T. Barnhardt, one of the proprietors of the new automobile laundry which opened New Year’s day at 175 Twenty-first street, says he has never seen the force of advertising so thoroughly demonstrated as in the case of the opening of the new industry in Portland last Monday.

The Oregon Daily Journal, January 7, 1912, Section 4, page 9.

Detroit

News of an “Automobile Laundry” in Detroit leaked out even before it was fully operational. Lew McCutcheon, Herbert Nelson and Frank McCormick organized the company with $10,000 capital. The new development was newsworthy enough to catch the attention of the automotive magazines. The story made a splash and was picked up and reported in dozens of magazines and hundreds of newspapers across the country.

Detroit to Have an Automobile Laundry.

Automobile Laundry is the style of a company which just has been organized under Michigan laws . . . the character of which is only indirectly suggested by its title. The laundry work which it will perform will be the washing and polishing of automobiles and the cleaning of engines by compressed air.

The incorporators of the company . . . are Lew F. McCutcheon, Herbert F. Nelson and Frank D. McCormack. The system which will be applied provides for the entrance at one door of a dirty car which, after making a complete circuit of the laundry, will make its exit through another door in spick and span condition, the process requiring only 15 to 20 minutes, different crews of men being employed.

Motor World, Volume 34, Number 5, January 23, 1913, page 32.

Detroit autoists are loudly proclaiming their opinion that the Automobile Laundry, which made its bow in automobile row this week, is filling a want that has been long felt in Detroit.

Cars can be driven into the garage or laundry at No. 1221 Woodward ave., through one doorway, left for 20 minutes and received through another doorway, perfectly clean. If the owner wishes, only the body, top, chassis, etc., of the car is cleaned. If he wishes, however, he can have his engine cleaned also. . . .

In the cleaning compressed air, water soaking, soaping, air drying and machine buffing are employed. The contents as well as the car itself are cleaned and the owner gets “Everything back but the dirt,” as the laundry’s slogan says.

Detroit Evening Times, February 15, 1913, page 9.

Popular Mechanics, Volume 19, Number 4, April 1913, page 515.

Some reports acknowledged that Detroit’s automobile laundry was based on an earlier one out West.

Following the lead of a Pacific coast concern there has been organized a “laundry” for automobiles in Detroit, Mich. The company has leased a garage and has adopted as its slogan, “Everything back but the dirt.” In the new establishment the whole process of washing and cleaning a car has been systemized in such a manner as to take but 20 minutes.

The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (Buffalo, New York), April 13, 1913, page 51.

And at least one report even mentioned Portland, by name.

It is difficult to think of anything more unique than an automobile laundry, but Detroit claims to have the only one east of Portland, Ore., and now that it has proven a success in this city others may take up the cudgels in other centers.

Detroit Evening Times, July 21, 1913, page 3.

Comments in a profile of Frank D. McCormick, who managed the Detroit auto laundry, give a sense of the novelty of a systematic, dedicated car wash business at the time.

One does not necessarily need a microscope these days to cast his optics on something that may become essentially a part of the world of automobiling. Sometimes these things come and go like the ever-perplexing will-o’-the-wisp, but quite often our horseless precincts are invaded by something strikingly unique and yet practical and beneficial.

Witness, the Automobile Laundry on North Woodward-ave. Comb the country from coast to coast and from Maine to the gulf and you will not see many institutions like it. It is probably natural, though, that we have one in our midst - a sure-enough place where water and suds - or preparations that remind you of water and suds, hold full sway, because Detroit is looked upon as the leader in the auto world. . . .

Detroit Evening Times, July 21, 1913, page 3.

Creating Detroit’s first “auto laundry” was not the most interesting thing about Frank McCormick. He once had dinner with the pianist Padarewski and the daughter of the painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema in Padarewski’s private rail car.v Inspired, perhaps, by their dinner with Ignacy, his wife helped organize Detroit’s first professional string quartet a few weeks later.vi

Paderewski was likely not interested in him, so much as in his wife. Ella Mae Hawthorne-McCormick’s father was a world traveler who had been a shipbuilder in Montreal and hotelier in London, Ontario.vii She spent 50 years in journalism, was “one of the first women reporters in Detroit”viii and sometimes a move critic.

She was also a pioneer in the radio business. She was the first manager of what is now Detroit’s WJR newstalk radio station. She worked for the the Detroit Free Press when they started the station, and they selected her to be manager.ix

Her husband’s car wash was not his first business and not his last. He and his father had previously been successful lumber exectives. They are said to have cleared more than $100,000 in their lumber business, of which they sank nearly $70,000 into their next project, the Lorraine, a “De Luxe” ice cream and candy palace in downtown Detroit.x

Detroit Free Press, June 9, 1907, page 43.

The Loraine was an artistic success (“The soda fountain, a magnificent combination of marble, mahogany, German silver and French plate glass”), but a dismal business failure. Frank McCormick blamed the people of Detroit - apparently they weren’t up to the “highest English and New York standards.”

“How do I account for it?” said Frank McCormick in response to a similar query. “The simple truth is that Detroit is not ready as yet to support an establishment conducted on the lines of The Loraine. It was too high grade. The Loraine was an experiment, and a more costly one than we had figured on.”

Detroit Evening Times, April 16, 1909, page 11.

Detroit may not have been ready for a fancy ice cream parlor, but they were apparently ready for an “auto laundry.” Following the early success of their first location, McCormick and his Detroit car wash investors quickly set their eyes on Cleveland - taking their Portland grunge removal system from Detroit Rock City to “Hello Cleveland.”

Detroit Evening Times, April 28, 1913, page 7.

An automobile laundry was “Takin’ Care of Business” in Winnipeg, Manitoba by June of the same year.

Gas Power Age (Winnipeg, Manitoba), Volume 9, Number 6, June 1914, page 25.

And there was one in “Uptown” Minneapolis, Minnesota (at Hennepin and Lake) by November.

Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), November 16, 1913, Third Section, page 12.

One year after opening his first automobile laundry on North Woodward, Frank McCormick opened another business closer to the Detroit River. The Central Garage took up an entire block along Jefferson Avenue, between Shelby and Woodbridge (Woodbridge, I believe, was one block south of Jefferson, running parallel to Jefferson, along the water). It had entrances on three levels, on Shelby, Woodbridge and Jefferson. Each level offered different services.

The upper level, with entrances on Shelby Street, was for the storage of trucks and commercial vehicles. The main level, with entrances on Jefferson, was for the storage of pleasure cars. The lower level, along Woodbridge, offered “washing of all kinds of motor cars, polishing, carbon cleaning, engine cleaning and in fact, the complete care of a machine.” They claimed to be the first garage in Detroit with a check-in system of cars, for security.

The convenient location of the Central will be appreciated by motor car owners who like to drive from their homes to offices and places of business, but are averse to leaving a machine standing on the street. Such an owner may send his car to the Central, using his storage space there in exactly the same manner that he would his private garage, having the privilege of taking his car in and out as many times during a day as he desires.

Detroit Evening Times, June 6, 1914, page 6.

Thomas Edison parked there (or so they claimed).

But despite the success of the business model, all was not well in auto laundry-land. One of the problems was that the name, “Automobile Laundry,” was ambiguous.

The Name

Before the first “automobile laundry” opened in Portland, a local newspaper said that the name “means just what the words imply.” News out of Detroit, however, suggested “the character” of the company “is only indirectly suggested by its title.” People were supposedly unsure whether the “Automobile Laundry” was a laundry for cleaning cars or a clothing laundry with an automobile.

That the weather condition during the past month and a half has had a great deal to do with the discontinuance of the business at 175 Twenty-first street, known as the Automobile laundry, cannot be denied. Many of the patrons of the place advance the idea that the name selected by the promoters of the enterprise did not convey to the public at large the true purpose for which the company was organized.

The name Automobile laundry did not impress the public with the fact that the company was in business for the purpose of washing and polishing automobiles in as clear a manner as it might. It was necessary for the lessor of the property to the Automobile Laundry company to cancel the lease to that concern and take the property over in order to protect his interest in the property.

The name Automobile Laundry has disappeared from the sign over the door and instead the name Automobile Washing, Polishing and Engine Cleaning company, the name adopted by the lessor when he took the property over.

It is announced that the establishment will be kept open in future both night and day and that the trade will be taken care of by the new concern with as much dispatch and care as was given by the old management. . . . This is a business enterprise that Portland has long felt the need of, and deserves better patronage than has been given it in the past. The prices for washing and polishing an automobile are said to be very reasonable.

The Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), February 18, 1912, page 7.

The fact that the same words had previously been used to designate a laundry collection wagon reveals a real possibility of confusion.

The city steam laundry, owned and operated by J. J. Hunter and George Caldwell, two of the town’s enterprising and hustling business men, has put an automobile laundry wagon on the city route. A large basket has been constructed on the rear of the Brush automobile and Monday morning it was making its first round. . . .

Messrs. Hunter and Caldwell figure that the installing of the machine on the city route will work to the convenience of their patrons and will save expense for them. Deliveries can be made quicker and with less cost than with the old gray horse and the wagon.

The Weekly Democrat Chief (Hobart, Oklahoma), September 14, 1911, page 7.

But the success of the expression, “Automobile (or Auto) Laundry,” at least following the widespread reporting of the opening of Detroit’s first car wash in 1913, suggests the early reaction may have been premature. Car washes were routinely referred to as “Automobile (or Auto) Laundry” into the 1950s. A car wash industry magazine called The Auto Laundry News is still in publication today, with an online presence at carwashmag.com.

“Car wash” appears to have eclipsed “Auto Laundry” as the more common title sometime after World War II, although the transition was already underway in the 1920s, when the “car wash” was one of the several services you could get at an “Auto Laundry.”

The Atlanta Constitution, March 28, 1920, page 8.

The name, “automobile laundry,” was not the only expression associated with early car washes to do double duty in the traditional clothing laundry business - their slogan did too.

The Slogan

The original Portland and Detroit “Automobile Laundries” both used the slogan -

“Everything Back But the Dirt.”

The slogan related back to traditional clothing laundries. It had been in regular use in association with laundries since at least 1902, and remained in widespread use through the 1930s, and occasional use into at least the 1960s.

The Marengo Republican (Marengo, Illinois), November 21, 1902, page 4.

Sioux City Journal (Sioux City, Iowa), May 1, 1905, page 5.

Lexington Herald-Leader (Lexington, Kentucky), March 2, 1906, page 4.

The World (Coos Bay, Oregon), November 24, 1908, page 4.

Growth of the Industry

The automobile laundry business continued to grow throughout the following decade, in lockstep with the expanding automobile market. Many of the familiar devices found in modern car washes made their appearance during these early years.

There were dozens of patents issued to dozens of inventors for various types of brushes with water or soap suds running through them, frequently referred to as “fountain brushes,” with rotating or other, various types of attachments, sponges or brushes at the end.

Several inventors received patents for various types of swinging or traveling overhead hose arrangements, which permitted the hose to be swung around the car without dangling directly onto the car, the kind one might find today in a coin-operated, do-it-yourself car wash.xi

Several people invented various all-around sprayer arrangements that could clean all sides of a car at the same time.

Washing Cars

An advantageous arrangement for washing cars in the minimum of time consists of four spray nozzles on the floor of the wash rack with their jets pointed toward the under surfaces of the mudguards, and a fifth nozzle fixed above the middle of the engine hood. This also is a spray nozzle, and spreads water over the forward section of the car. A single valve operates all the nozzles jointly. . . .

While the spray is working, the car washer has an opportunity to prepare his soap and water solution, which is applied with sponge to the body and brush to the running gear. The final rinsing of the car is then started with the hose and finished with the fixed nozzles. With one wash rack equipped in this manner twice the number of cars can be washed in the usual length of time. - G. A. Luers.

The Lewiston Daily Sun (Lewiston, Maine), May 29, 1922, page 5.

The Automatic Automobile Laundry Company of Memphis has just been incorporated to operate under the patents of J. S. Englerth, M. G. Hornaday and B. A. LaBundyxii for the establishment of a new and high class method of washing, cleaning, polishing and special care of cars. The system is a decided innovation over the methods formerly used and it is intended to inaugurate in this connection a high-class service without additional charge that will eliminate delays and wasted time. The above view shows one-half of the apparatus at work.

The Automatic Auto Laundry as controlled by patentees, consists of washing with nine batteries of 12 water sprays each, automatically controlled and without use of soapy water. The drying will be done by compressed air. Vacuum will be used for cleaning the inside of the car when desired and the car will be polished with a system of especially constructed rotary buffers filled with soft camel-hair, eliminating the usual rubbing.

The Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), October 22, 1922, page 13.

In December of 1922, a man named Edward H. Lostetter, of Cincinnati, Ohio, filed a patent for a similar car wash arrangement. Lostetter was the manager of the Quick Service Auto Laundry Company at the corner of Court and Race streets in Cincinnati, in a building still occupied by an automotive-related company - a tire store and service station.

Lostetter died before his patent issued, but not before he sold his patent rights.xiii He assigned his patent to a man named Thomas F. Costello of Cincinnati. Costello had big plans. After securing the patent rights, he founded the National Quick Service Auto Laundries Company, with the intent to “operate quick service auto laundries in the principal Eastern cities of the United States.”xiv He opened a location in Washington DC within weeks of that announcement.

Evening Star (Washington DC), February 6, 1924, page 26.

It is not clear whether and to what extent Costello expanded his market reach. But he was not the only one with plans to market his car wash system to a broader region or nationwide. Others succeeded where he may have failed.

Spray Systems

Other advances in car wash technology took the form of improved spraying systems. At least two such systems formed the basis of companies with national reach, the Klean-Rite system out of Chicago, and the Gates system out of St. Louis.

Klean-Rite

In 1922, Jacob P. Nicholson filed the first of his two car-wash patents, which would form the basis of the Klean-Rite auto laundry system.

Englewood Economist (Chicago, Illinois), January 23, 1924, page 3.

Based in Chicago, the Klean-Rite system was adopted in automobile laundries across the country. The heart of the Klean-Rite system was Nicholson’s patented array of hot water, cold water, soap and compressed air, alternately delivered through a single nozzle, and powered by high pressure air. His original patent also described the use of a pit, with the car suspended above the pit, so workers could more easily clean the undercarriage of the car, and have more of the car at eye-level to make cleaning easier. He later received a patent for such a pit, having curbed runways for positioning the car over the pit.

In watching operations at the Klean-Rite Auto Laundry, we are reminded somewhat of the familiar scene in a tonsorial parlor. In this case, it is not the man but the car which is “next.” A car to be cleaned enters the portals of the garage, and is checked. The owner or driver is politely offered a comfortable wicker chair in which to wait at ease while his automobile is undergoing the various cleansing stages.

The first step in the process is a thorough cleaning of the inside of the car by compressed air. The top is dusted by hand. The automobile is then rolled over a pit. . . . The washing of the car is ordinarily done by two “pitmen”; but when business is brisk four men are engaged. At two points on each side of the pit four pipes converge and terminate in single connections. One of these pipes delivers cold water . . .; another is a hot-water-feed pipe . . .; the third furnishes the soap solution; and the fourth pipe is the compressed air line. . . .

With two men to do the cleaning, only seven minutes are required from the moment the car is rolled over the pit until it is moved away to make room for the next one. . . . When the car in hand has been pushed off the pit and rolled ahead about 15 feet, two men with hose lines are put on the job of washing it down with cold water at the ordinary pressure maintained in the city main. This rinsing takes two minutes. With this done, the car is pushed a little farther ahead. Two men, known as “chamoismen,” now jump to do their part of the task. . . . When the chamoismen have finished, a nickel polisher comes along and gives the machine the final touches.

Compressed Air Magazine, Volume 31, Number 2, February 1926, pages 1541-1543.

Klean-Rite operated under the franchise system; the system used under license, but locally owned.

One of the outstanding successes in [the auto laundry] field is that of the Klean-Rite system, a chain operating in many cities under license from a central office at Chicago. The Klean-Rite laundries are individually owned, but are kept to a general standard of service and in the major details, to a formulated method of procedure, which has been worked out from considerable experience and study by the head of the system, J. P. Nicholson.

Petroleum Age, Volume 17, Number 5, March 1, 1926, page 28.

By 1927, there were Klean-Rite auto laundry systems operating in at least, Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, Washington DC, Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Quebec, South Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, California, and Hawaii.

Klean-Rite may have been the biggest name in the business at the time, but they were not the only company to take their auto laundry business national. A man named William Gates started in St. Louis, and later took his system to Southern California, where it may have inspired the next generation of car washes.

Gates

The Gates system involved first spraying a car with a grease solvent, generally kerosene, which would loosen accumulated grease, oil and grime, making it easier to then wash off with soap and water. One of Gates’ investors held a patent in his own name, for a system for combining water with high pressure compressed air in a single stream, to do more cleaning with less water, which was said to be particularly suited for use in regions where water was scarce and/or expensive. A third patent, also in Gates’ name, claimed an atomizer valve for used in a car was sprayer system, also said to be particularly suited to places where water was scarce.

An automobile laundry is operated in St. Louis in which cars, no matter how dirty, are cleaned in 15 minutes. All this is accomplished through combinations of air and water, oil and water, or oil and air under high pressure. The body, top, upholstery, engine and chassis are cleaned and dried through this system.

The Pittsburgh Press, January 20, 1924, Automobile section, page 2.

William J. Gates, of St. Louis, filed a patent application for his degreasing machine in February 1923.xv He was the owner/operator of the Gates Auto Laundry and Supply Company on Delmar Boulevard, which had been in business since at least 1921.xvi

The place where your car will be laundered right,

Thoroughly cleaned inside and out,

Work is done within your sight,

It is the place people talk about.

. . .

Gates’ Auto Laundry

Delmar and Goodfellow Aves.

The Modern View (St. Louis, Missouri), September 30, 1921, page 72.

By August of 1923, however, the Baderacco brothers, Louis and Joseph, had acquired Gates’ business, and also formed a new company, the Auto Laundry System Company. It is not clear when they acquired Gates’ business, but the auto laundry business was on their minds by April of 1923, when Louis J. Badaracco filed a two patent applications, one for an “appratus for cleaning automobiles” and another for a “method of cleaning automobiles,” using a combination of kerosene, compressed air and water. Both patents were assigned to the Auto Laundry System Company.xvii

The Badaracco brothers were saloon operators who were forced to find other sources of income following the start of national prohibition a couple years earlier. Coincidentally, they would both die in bed of “heart disease” following acute episodes of “indigestion” or “gastritis.” Louis died at home in his own bed. Joseph, on the other hand, died scandalously in his secret love-shack, where he was discovered by his girlfriend, Leona Ziegenhein, the wife of the son of a former mayor of St. Louis. When they died in the mid-1930s, they were associated with three, related car wash companies, the Auto Laundry System, the Auto Laundry Company and the Gates Auto Laundry and Supply Company.

The Gates system’s suitability for arid climates made it a perfect fit for California. The brothers took advantage of that fact and were in business there by March of 1923. They found a willing investor in Albert Wimsett, the national director of the Loyal Order of Moose.

Albert Wimsett, Los Angeles Herald, September 28, 1915, page 5.

An automobile washed, polished and cleaned in six minutes - that is the revolution in giving the motor car its weekly or semi-monthly bath that is promised by the introduction in Los Angeles of an automobile laundry system, the first of which plants is now in course of construction at Vermont avenue and Frances [(sic, should be Francis)] street. A second plant is also under way on Vine street, between Sunset and Selma.

Albert B. Wimsett, originator of the Wimsett system of industrial and financial organization, is at the head of the Gates-Wilshire Automobile Laundry, which will be in operation about April 15, and which plant will have a capacity of 225 cars every 24 hours. . . .

The Gates system was introduced two years ago with great success in St. Louis, where the experimental station is located. The first plant has just began operation in Springfield, Ill., and the second is now being established in Los Angeles. The third plant will be opened in Hollywood about April 20 and will have a capacity of 300 cars every 24 hours.

Mr. Wimsett controls the installation of the Gates system automobile laundries in seven western states, and he is confident that the systematic washing, polishing and cleaning of automobiles will spread with great rapidity.

Los Angeles Evening Express, March 22, 1923, page 8.

Los Angeles Times, July 12, 1923, page 7.

Albert B. Wimsett, who at one time served as the national director of the Loyal Order of Moose, was also the founder the the “Wimsett System” of banking, which made possible the creation of community-based savings and loan institutions. In Los Angeles, however, the Gates system of car washing was frequently referred to as the “Wimsett System,” based on Wimsett’s local financial backing.

Los Angeles Times, July 12, 1923, page 7.

Gates et al. did not settle for simply building their own auto laundries, they were also in the business of selling equipment to small-time, individual operators, like service station owners with a wash rack.

Howard M. Moore built his new Motor Service Station with one idea in mind - to render the most efficient service possible.

For Wash Rack Equipment of course, he chose

GATES AUTO LAUNDRY EQUIPMENT

Gates is the only equipment efficiently employing air and water alone. Cleans rapidly without injury to the finest finish.

Los Angeles Evening Citizen News (Hollywood, California), January 29, 1926, page 6.

Presumably, the Badaracco brothers were also selling equipment through one of their various car wash companies back in St. Louis.

The Gates/Badaracco/Wimsett companies were not the only people selling car wash equipment to small operators. At least two companies with extensive experience in the crop-spraying industry adapted their technology to enter the stand-alone car wash market, selling to garage and service station owners. And both of those companies, the Hardie Manufacturing Company and the John Bean Manufacturing Company, would later join forces with pioneering car wash companies in Los Angeles, to provide the sprayers for the first large-scale, “semi-automatic” car wash systems, in which the cars were moved through the car washes by conveyor systems.

Bean

Sonoma West Times and News (Sebastopol, California), February 17, 1917, page 8.

John Bean founded the Bean Spray Pump Company in 1883. They were a “a pioneer in developing power spray pumps and dusting machines for protecting deciduous and citrus fruit orchards from insects and diseases and in building pumps for irrigation.”xviii They later expanded into machines for protecting field crops and for washing fruits and vegetables before marketing.

Lynden Tribune (Lynden, Washington), February 2, 1911, page 2.

A former Bean employee named Vernon Edler,xix whose company was Bean’s Southern California distributor,xx applied Bean sprayer technology to washing cars sometime in the mid-1920s. The date is not certain, but a stock offering issued in 1928 said the “new use of spray pumps for washing automobiles was discovered several years ago.”xxi Initially, Edler sold “small, one-man car washing plants.”xxii He was so successful that by the mid-1920s, there were hundreds of people “Workin’ at the Car Wash” in Los Angeles, helped by new advances in car-wash technology by Bean Spray Pump Company car wash units, sold by Vernon Edler.

Your car should have a weekly bath to keep it clean, bright and new.

Seventy thousand cars washed per month by three hundred up-to-date service stations and garages in and about Los Angeles, using this System.

Fleet owners should investigate - big savings in time and a better washed car or truck. No steam, no injurious sprays used. . . .

VERNON EDLER CORP. . . . Los Angeles, Calif.

A product of BEAN Spray Pump Company, San Jose, Calif.

The Los Angeles Times, March 27, 1927, part 6, page 2.

Vernon Edler, president of the S. E. S. Company, developers of the Bean system of car washing, has given this very important subject of automotive upkeep long and careful study. He has overcome many objectionable practices. . . .

The Bean system is purely hydraulic, the idea being through the use of a high-pressure pump to develop a fine velvety mist, so fine and penetrating that it softens the caked mud, flushes out inaccessible crevices and flows the dirt off like magic.

The Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1926, part 6, page 16.

Los Angeles Times, April 3, 1927, part 6, page 9.

Have New System for Washing Cars

California is setting the pace for the nation in the development of a new system of car washing which is unsurpassed in leaving a shiny finish, according to Vernon Edler, of the Bean Spray Company. . . .

Ed Tarver and Bert Moundson, proprietors of the local station, known as the “Midway Wash and Grease Rack,” are long experienced and capable men in their line. They have in their time tried about all makes of car washing systems known. But of all systems Bean Rapid Car Washer, has given them the best results.

Ventura County Star (Ventura, California), April 30, 1927, page 2.

J. J. Henry operates the Brite-Lite Garage, Inc., at 4939 York Road, Philadelphia. . . . Until Henry installed his washing system, a Bean two-gun outfit of high pressure hydraulic type, electrically operated, he had averaged only between $33 and $40 a month from washing his customers’ cars. He did not install the device until the latter part of September. In August, the last month he employed hand washing, he took in at the stand just $37.50.

In October, the first complete month in which he used the mechanicl car washing system, his revenues from the wash stand amounted to $209.75 in cash . . . .

American Garage and Auto Dealer, Volume 17, Number 7, July 1927, pages 12-13.

Bean’s orchard sprayers looked very similar to those made by another sprayer company that would enter the car wash-spray business, Hardie Manufacturing Company’s “Orchard Gun.”

California Citrograph, Volume 4, Number 4, February 1919, page 95; Citrus Leaves, Volume 8, Number 5, May 1928, page 34.

Hardie

Henry H. Hardie started the Hardie Manufacturing Company in Hudson, Michigan in the early 1900s. The date is uncertain. An advertisement from 1916 says they had “12 years experience,” and an advertisement from 1918 says it had “18 years” experience, which would place their founding in either 1904 or 1900. The earliest patent found in a search of an online patent database dates to 1901, issued to a Francis Robert Hardie, for a “spray pump,” and assigned to the Hardie Spray Pump Company of Detroit, Michigan. An “H. H. Hardie,” presumably Henry H. Hardie, signed as a witness to that patent.

Smyrna Times (Smyrna, Delaware), February 14, 1906, page 3.

Between 1911 and 1917, Henry H. Hardie would receive at least three patents, all assigned to the Hardie Manufacturing Company of Hudson, Michigan. One was for a “tree-spraying device,” one for a “nozzle,” and one for a “fruit grader” (sorter). When he died in 1935, it was said that he “commenced his career with the development of the first power sprayers known and was an outstanding figure in the history and development of spraying equipment during the last 50 years. Hardie was founder and president of the Hardie Manufacturing company.”xxiii

By 1926, Hardie was in the business of selling car washing spray units.

A high pressure car washing system is provided by the Hardie Car Washer. A pressure of 300 lb. is available at the nozzle to loosen accumulations of mud and grease from the under parts of the chassis. By a quarter turn of the handle of the gun the powerful stream can be cut down to a fine spray that will cleanse a highly polished surface without injury.

The compactness of the Hardie machine is one of the features. The makers call attention to the fact that it can be installed in a corner of the garage or hung from the ceiling.

Commercial Car Journal, Volume 31, Number 2, April 15, 1926, page 50.

Both Bean/Edler and Hardie would profit from the next big thing in car washes, the large-scale conveyor systems. Hardie and Edler would supply some of the earliest ones built, and Edler would receive a patent on his own conveyor system, and later leverage his success in the car wash industry to merge with Bean, eventually becoming a major shareholder and executive with a large, multi-national conglomerate, now FMC. But neither Edler nor Hardie were the originators of the conveyor car wash system. That honor belonged to the former mayor of San Diego and a hotel tour bus operator.

Semi-Automatic

Louis J. Wilde and Bleeker K. Gillespie reportedly developed the idea of the "semi-automatic" car wash (in which the car is automatically moved from station to station) after long study and consideration.

As Henry Ford turns out a completed car every minute by moving platform process - the new Automatic Circular Laundry cleans any automobile, inside and out, bottom and top, turning out a thoroughly cleaned car every minute in the day by the new patented circular moving platform system. It is fool-proof and does the work.

The patent was secured through Munn & Co., Patent Attorneys, and publishers of the “Scientific American,” and is owned by two Los Angeles men, who have spent many months - East and elsewhere - compiling data and mechanical effects to perfect this ingenious Super-Service Station. Los Angeles is to have the first circular automobile cleaning plant built in America. Work will start on the new building immediately.

Los Angeles Times, August 31, 1925, page 15.

The Inventions

The “patent” discussed in this article was likely at the time just a patent application. Louis J. Wilde and “Bee” K. Gillespie (as he styled himself) had filed two patent applications earlier that year. The first-filed patent was for a circular car wash, with a rotating platform that carried cars through various stations. Their second-filed patent was for a straight-line car wash, with two linear conveyor belts carrying cars in opposite directions, with a turntable at the end to swing the cars around from the end of one conveyor to the beginning of the next one.

From its inception, the Wilde-Gillespie system appears to have had all of the earmarks of a modern semi-automatic car wash.

At intervals around the movable platform are arranged suitable apparatus for manipulation by the operators to effect a thorough cleaning and polishing of an automobile so that during the travel of an automobile from the discharged end of the stationary platform to the receiving end thereof it is successively subjected to the several cleaning and polishing operations.

US1613213.

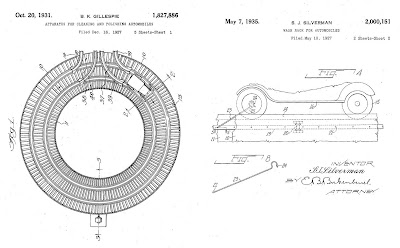

Gillespie later filed a third patent application, in his name alone (filed December 1927), for a modified rotating platform. A third inventor, Samuel J. Silverman of Portland, Oregon, filed a patent application which he assigned to the Gillespie Auto Laundry System, Inc. (filed December 1927), which replaced the rotating or moving platform with a continuous chain, with hooks that engaged with a car’s axle to pull the car through the various stations of a car wash, which significantly reduced the size and cost of the machinery necessary to power a semi-automatic car wash.

B. K. Gillespie also received a patent (filed December 1927) on a system with rotating brushes, similar to those still used in car washes today. In his version, the brushes were apparently only intended for the roof of the car. Gillespie did not invent the rotating brush system, however. When he filed his patent, similar devices had already been in use for decades in the railroad industry to clean locomotives and rail cars. Gillespie’s patent may be the earliest such patent with specific application to automobiles.Vernon Edler also received at least two semi-automatic car wash patents. He received a Canadian patent for a straight-line, semi-automatic car wash system using a continuous chain-drag conveyor, and a US patent for a specific type of chain-drag hook release, but both of his patents were filed after those of Wilde, Gillespie or Silverman.

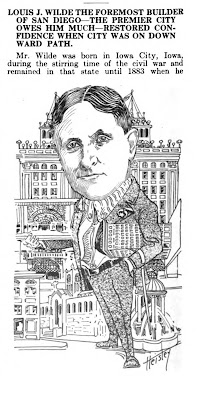

The Inventors

|

Out West Magazine, October 1912, page 264. |

Louis J. Wilde

From newsboy to banker is the boast of Louis J. Wilde, San Diego promoter.

Muskogee Times-Democrat (Oklahoma), September 12, 1913, page 4.

Louis J. Wilde was an inventor, entrepreneur, banker, real estate and oil investor, and former mayor of San Diego when he entered the automobile laundry business in about 1925. It is not clear how, when or why he took an interest in car washes, but, coincidentally, he had been in Portland, Oregon, facing charges of embezzlement, when the first “automobile laundry” opened its doors in January 1912. The charges stemmed from the sale of Omaha Home Telephone bonds and his allegedly “splitting” his commission with a cashier of the bank. He was acquitted of any wrongdoing.

|

| Oregon Daily Journal, July 2, 1911, page 8. |

Interestingly, during his trial, Wilde’s name appeared on the same page as an unrelated reference to a local attorney named Samuel J. Silverman. More than a decade later, Silverman assigned his own car wash patent to Wilde’s business partner, B. K. Gillespie. It seems likely that his relationship or acquaintance with Wilde began in Portland. Although it’s not clear how, when or why he became interested in the car wash business, it is known that he drove a car. In September of 1920, Silverman was arrested, along with forty-eight other drivers, for “cutting corners,” in a crackdown on dangerous drivers.xxiv

|

| Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), March 23, 1914. |

Wilde, Louis J., Banker, San Diego, Cal., was born in Iowa City, Ia., July 16, 1865, the son of John and Lucina Wilde. He married Frances E. O’Brien, daughter of James O’Brien, former county auditor of St. Paul, Minn, in that city, and to them there have been born four children, Donald E., Richard E., Jack D., and Lucille B. Wilde.

Mr. Wilde was educated at Cornell College, Mount Vernon, Ia., and at Hyatts Academy, Iowa City, Ia.

He left his native city in 1884 and went to Los Angeles, Cal., and for the succeeding years was a resident of that city, where he worked at various occupations from elevator boy up. He was in the real estate and insurance business about the time of the boom, 1893, after which he moved to St. Paul, where he was in the brokerage business for nine years more. At the end of that time, or in 1903, he moved to San Diego, Cal., there to make his permanent home.

Press Reference Library, Notables of the Southwest, Los Angeles, Los Angeles Examiner, 1912, page 456.

The questions start at the beginning. Where was he born? He is frequently said to have been born in Iowa City, Iowa, although widely circulated reports of his death gave the place of birth as Marshalltown, Iowa. Curiously, an item in the Marshalltown Times-Republican in 1914 refers to “Louis J. Wilde, a former Iowa City merchant,”xxv and his obituary in the Iowa City Press-Citizen in 1926 refers to him as “a native of Marshalltown, Iowa.”xxvi

But wherever he was born, the 1880 US Census shows his family in Le Mars, Iowa, his father John Wilde listed as a “retired merchant,” though only 47 years old. The same census gives Louis’ age as twelve, which casts the suggested 1865 birth year into question.

The Wildes’ connection to Le Mars is corroborated by comments made in 1941 by an old-timer from Monrovia, California, who recalled having being met at the station in Los Angeles by “old Le Mars, Iowa, friends,” including John Wilde, when he arrived there in 1887.xxvii The old-timer was a man named J. F. Sartori, who in 1941 was the Chairman of the Board of the Security-First National Bank in Los Angeles. He also recalled that John Wilde was one of a small group of men who petitioned the Comptroller of the Currency for permission to organize the First National Bank of Monrovia. Years later, in advertisements for various investment schemes, Louis J. Wilde would claim to be a former bank officer of that bank. Years later, Louis J. Wilde would petition the Comptroller of the Currency for permission to open the National Bank of San Diego.

His family living in Le Mars is also consistent with a comment made in an article about Louis J. Wilde in a newspaper in 1885, which said his “father lives in northern Iowa” (Le Mars is in the northwest corner of the state). That same article also raises questions about his supposed education at Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, and his matrimonial history.

The article appeared in the Rock Island Argus, of Rock Island, Illinois. It recounts an exciting “race for a wife” that had taken place the day before, across the River from Davenport, Iowa, between two rivals for the affection of “a handsome young lady named Mamie E. Shackley,” a “dudinexxviii of the first water” who “used to make the boys’ hearts palpitate as she glided around like a swan at the skating rink” (the “skating rink” comment was not merely poetic license; Mamie had won a roller skating contest the previous yearxxix).

Mamie was a typesetter for the Davenport Gazette, who had winnowed her choices of a man down to two. One of them, however, had moved to Minneapolis, while the other one stayed in Davenport. The “Davenport dude” believed that he had the inside track, and was surprised when the “Minneapolis youth” returned, bought a marriage license, married Mamie and returned to Minneapolis, all in one day. The victor?

His name is Louis J. Wilde. His father lives in northern Iowa, and last summer sent him to the Davenport Business college, but he spent most of his time in having fun with the boys. He was employed for a while on the Herald, and was ruled out of the editorial room on account of the over abundance of perfume he daily poured on himself.

The Rock Island Argus, January 17, 1885, page 4.

It is not clear what Wilde was doing in Minneapolis at the time, but whatever it was got in some hot water - although he beat the rap.

CRIMINAL MATTERS.

The case f the State vs. Louis J. Wilde, indicted for obtaining money under false pretenses was dismissed by Judge Koon.

The Saint Paul Globe, March 18, 1885, page 3.

Two years later, the Quad City Times of Davenport, Iowa reported that, “Louis J. Wilde, who left this city about a year ago for the far west, is located at Monrovia, California, engaged in real estate.”xxx And for the following several years, Louis J. Wilde’s name, and his fathers, appear in reports of numerous real estate transactions, mostly in and around Monrovia, east of Los Angeles. The name, “Wilde,” even appears in connection with a real estate development apparently named after their former hometown of Le Mars.

|

Los Angeles Times, February 25, 1888, page 3. |

In September 1889, he advertised a desire to trade 40 acres of farmland in Monrovia for city property. At about the same time, he began advertising numerous lots for sale within the city of Los Angeles. In November of 1889, he showed up in Topeka, Kansas, looking to exchange southern California real estate for “anything” in Kansas.

After 1889, Louis J. Wilde’s name disappears from southern California newspapers, although his father’s and mother’s names continued to appear regularly in reports of real estate transactions, mostly in Monrovia. The name, “Louis J. Wilde” pops up again in connection with St. Paul, Minnesota in 1891, but not in a good way. If this refers to the same Louis J. Wilde who later served as Mayor of San Diego, perhaps he was a scoundrel.

Reliable information was received by The Inter Ocean correspondent to-day of the whereabouts of Louis J. Wilde, the defaulting cashier of the St. Paul Loan and Trust Company. Wilde, who has a weakness for loud English style clothes, formerly lived here, where at one time he was cashier of the National Exchange Bank. He left St. Paul last summer for his vacation, and came to this city. During his absence the company found him short in his accounts several thousand dollars, and detectives started out in search of him. He mysteriously disappeared and all trace of him was lost. He is now at Paddington, England, but what his occupation is is not known. He evidently skipped the country immediately after his defalcation was discovered.

The Inter-Ocean (Chicago), January 10, 1892, page 9.

Chicago and St. Paul would be two places Wilde would eventually return to, before moving to Southern California for good in about 1903. But no other information about this alleged embezzlement could be found. There were, however, at least two more frauds committed by someone identified as Louis J. Wilde during this period. In Cincinnati in 1891, someone he induced to become his business partner claims a Louis J. Wilde absconded with the money shortly after misrepresenting the value of the merchandise to be sold.xxxi A nearly identical accusation popped up in St. Louis, Missouri at the end of 1892.xxxii

It is impossible to say whether this was the same person. But when that person showed up again, it was in the form of someone possibly selling shares in something that may or may not have panned out. He would repeat the pattern several times. In each case, there was a lot of hyperbole while the money was being raised, and little or no news of any success after the fact.

In 1897, the name of Louis J. Wilde, of New York, pops up as an “expert mining engineer,” the public face of the Klondike-Alaska Gold Mining, Transportation, and Trading Company of Illinois, organized to profit from the recent Klondike gold rush.xxxiii

Louis J. Wilde, vice president of the Klondyke-Alaska Gold Mining, Transportation and Trading Company, claims that his concern has “struck it rich” in the gold fields. His party is expected to start in a few weeks and join the staff of prospectors that has already been sent into the interior.

The Chicago Chronicle, August 14, 1897, page 7.

Wilde claimed to have hired a chemist with a secret “process by which ice may be melted chemically in about one-tenth of the time usually employed.”xxxiv Wilde was said to be set to leave Chicago on September 5th, “in company with a number of other experienced prospectors and men who will be useful. They will proceed as rapidly as possible to the gold fields and commence systematic prospecting.”

Among the party which will leave Chicago September 10 under the leadership of Louis J. Wilde, vice president of the Klondike-Alaska Gold Mining, Transportation & Trading company, will be a man learned in the habits of molecules, atoms, gases, etc., and in the handling of the same. According to Mr. Wilde, their chemist knows of a means of getting through snow and ice by the use of a chemical compound which costs very little and nearly all of its ingredients can be procured in Alaska.

The News Tribune (Tacoma, Washington), August 14, 1897, page 8.

Wilde left Chicago on time, but he did not head to Alaska. He went to Rochester, New York. His wife died soon after their arrival, leaving her husband with two children.xxxv

He was now Louis J. Wilde, of “New York and Chicago; ex-vice-president Alaska Transportation, Mining and Trading Company,” now the President of the newly-formed Alaska Milling, Mining and Trading Company.

The company has been fortunate in securing the services of Mr. Louis J. Wilde, of the Alaska Transportation Company of Chicago. His personal knowledge of Alaskan affairs, mining, engineering and transportation enables him to render valuable services to this company.

Democrat and Chronicle, October 3, 1897, page 13.

The company took out several full-page advertisements in Rochester newspapers, hyping the opportunity to invest in the company for $1 per share. He appears to have been actively planning some sort of expedition. News items reported on a trip to New York, and a trip to Washington DC to examine maps and surveys of Alaska in preparation for the expedition. Wilde appeared in Seattle in December, with two other members as an advance party, and gave a lengthy interview to a local reporter on their preparations and plans. The main party left Rochester in February 1898,xxxvi and the the company established an office in Victoria, British Columbia.xxxvii

No more references to the company have been found anywhere after the initial fund-raising and departure. No more references to Louis J. Wilde show up in newspapers until 1899, when his name shows up as a recent registrant at a resort hotel near Minneapolis, the Hotel Lake Park. Over the next two years, his name appears in numerous reports of real estate transactions in and around Minneapolis, and in classified ads, seeking to trade real estate for a stock of goods or jewelry. As he had done several years earlier in Los Angeles, he sometimes advertised property in Kansas.

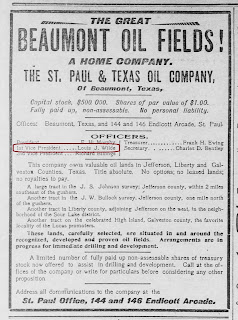

Beginning in April of 1901, and for about the next two years, Wilde was in the Texas oil business, reportedly purchasing 200 acres near Beaumont. Shortly afterward, he started advertising the sale of shares in oil drilling ventures. The shares were hyped in print advertising similar to that used a few years earlier to sell Klondike gold-rush shares, with full-page advertisements and breathless hyperbole about the value and success or potential of their wells, or planned wells. His father, referred to as “Redondo’s pioneer fisherman,” reportedly left southern California that summer to work with his son on the project.

Wilde first offered shares in the St. Paul & Texas Oil Company of Beaumont, Texas.

|

| Saint Paul Globe, June 9, 1901, page 14. |

Soon afterward, he shifted to the United States Fuel Oil Company, with assets in the same region. And again, similar to what he had done in advertising his second gold-rush company, he touted as one of his qualifications that he was the “ex-Vice-president of the St. Paul and Texas Oil Co.” His father’s name appeared in some advertisements as treasurer of the company, citing as one of his credentials that he was the “ex-Vice President First National bank, Monrovia, Cal.”xxxviii

|

Minneapolis Journal, August 24, 1901, page 3. |

The following year, Wilde was selling shares in Kintla Oil, with oil drilling rights in Montana.

|

| Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana), March 30, 1902, page 11. |

In early 1903, there was a report that Wilde had sent representatives to Mexico to look after his interest in some gold fields. A few months later, he started selling off all of his St. Paul and Minnesota holdings.

Louis J. Wilde moved to San Diego in late-1903 or early-1904. By May, the United States’ Controller of Currency had approved Wilde’s application, made with partners including Ulysses S. Grant, Jr., to organized the American National Bank of San Diego. It was the first of several San Diego area banks Wilde would start, including banks in Escondido, Ramona, National City, and Oceanside.

Wilde invested in a streetcar line in National City and built the Pickwick Theater, among other local developments. In 1905, Wilde, U. S. Grant, Jr. and others announced their intention to build the U. S. Grant Hotel in San Diego. That same year, a syndicate bought land to erect the hotel on property formerly called the Gay Ranch.

Their private funding would ultimately fail, but efforts to secure public funding for the project eventually panned out. Wilde led fundraising efforts and Grant, Jr. oversaw construction of the hotel. Completed in 1910, the U. S. Grant Hotel is still in operation today. Louis J. Wilde donated the fountain, that still graces its grounds, as a “monument to the spirit and enterprise of San Diego.”

Wilde ran for mayor of San Diego in 1917, on the “smokestacks not geraniums” platform. He promised to prioritize business interests over beautification projects. He won, served two terms, and left office in 1921. He moved to Los Angeles at some point in about the mid-1920s, where he pursued oil and real estate interests.

Louis Wilde and Bleeker Gillespie appear to have been well acquainted long before they filed their car wash patents. In 1922, for example, Wilde appeared in the same photograph with Gillespie’s wife at the christening of a sixteen-inch drill at the “spudding in” of a new oil well.

Los Angeles Times, March 15, 1922, part 2, page 12.

Wilde’s interest in the car wash business may have been related to his oil interests, since car washes were a natural point of sale for petroleum products. At the time, automobile laundries and service stations with a wash rack generally provided other maintenance services, including gas, lubrication and oil changes, and in some cases using kerosene as a cleaning agent. In 1923, Louis J. Wilde filed for a trademark for “Red Devil” and logo, for “lubricating oil, gasoline, kerosene and sump oil.”

Louis J. Wilde was also a real estate developer. He sub-divided and developed a neighborhood in Glendora, California (near his old stomping grounds in Monrovia), bounded by Foothill Boulevard, Carroll Avenue, Barranca Avenue (then apparently called Ben Lomond) and Valencia Street.

|

| Los Angeles Times, November 18, 1923, page 19. |

In January 1926, Wilde purchased “income property” in Los Angeles, a “twenty-four-room-flat building at Fourth street and Rampart Boulevard,”xl on the southeast corner.xli That building, said to have been built in 1920, is now the eight-unit apartment building located at 400 South Rampart.xlii

Wilde also planned to build a hotel in Los Angeles, “a $1,000,000 hotel for workingmen, something on the order of the Mills Hotel in New York City.”xliii In 1924, Wilde took out a 100-year lease on the Arcadia Block, at the corner Los Angeles Street and Arcadia Street, with the intent of building the hotel there.xliv The hotel was never built, and the Arcadia Block was demolished in 1927. The reason the building was never built may be his death, following an operation in April 1926,xlv at about the same time his first automobile laundry became operational.

Although the earliest reference connecting Wilde to his car wash partner, B. K. Gillespie, appeared in Los Angeles in 1922, chances are that the pair knew each other in San Diego at least a decade earlier, where Gillespie had managed the auto livery and tour bus concessions at the U. S. Grant Hotel.

|

B. K. Gillespie, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 12, 1928, page 12S. |

One of the best known and most widely popular men in San Diego is B. K. Gillespie, owner of the U. S. Grant Hotel Auto Livery and manager of the San Diego Sight-Seeing Company. He was born in Bryan, Ohio, February 15, 1881, and is the son of R. H. and Mary F. Gillespie. After attending the public school he completed the course at Rio Grande College and in 1906 came to San Diego, where he started in the auto livery business.

San Diego County California, a Record of Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement, Volume II, Chicago, S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1913, page 217.

Bleeker K. Gillespie, who styled himself “Bee” K. Gillespie, and was frequently referred to as B. K. Gillespie, came to California from Ohio to California in the early 1900s. In 1904, he purchased property in Fruitvale Glen in Alameda. He married Bessie L. Northrop in Los Angeles in 1906, and was still listed as a Notary Public in Alameda County in 1907.

He appears to have been in the automobile business in San Diego by 1908, when an item in a Los Angeles newspaper reported that “B. K. Gillespie of San Diego” had recently purchased

some Oldsmobiles at a local dealership.xlvi In 1909, he purchased some seven-passenger Oldsmobiles from another Los Angeles dealer.xlvii

It is not clear his relationship with the U. S. Grant Hotel began, but by 1911, the year after the hotel was finished, he was doing well enough to build a “two-story mission residence” at 1510 29th Street in San Diego. A San Diego city directoy lists him as running an “auto livery” out of his home address in 1912, and a report of a tourist trip to San Diego from the same year refers to his company, the San Diego Sight-Seeing Company, as picking up travelers from the train station and bringing them to the U. S. Grant Hotel. An advertisement for the San Diego Sight Seeing Company in 1914 gives its office address as the “main entrance U. S. Grant Hotel.” A 1915 city directory lists him as being associated with both the U. S. Grant Hotel Auto Livery and the San Diego Sightseeing Company.

Standard Guide to Los Angeles, San Diego and the Panama-California Exposition, San Francisco, North American Press Association, 1914, page 88.

Gillespie did not simply run a tour bus operation, he embraced automobile touring as a pioneer RV camper in a converted tour bus, tricked-out as a “Luxe Bungalow Auto.”

Traveling in a bungalow palace car, a de luxe addition of one of the San Diego sight-seeing automobiles, B. K. Gillespie and party reached this city yesterday on a tour over the southern end of the state. They pitched camp near the corner of Mr. Vernon avenue and Mill street for the night.

Gillespie is manager of the San Diego company and conceived the idea of fitting up one of the autos. The improved body is 26 feet long and much wider than the average machine. There is a kitchen, living room and observation room, while in the rear there are places for four spring bunks, while the whole traveling house is fitted up with every convenience for living on the road.

San Bernardino County Sun, August 22, 1913, page 5.

Twenty years later, following the success of his car wash business, he and his wife traveled around in a white leather-lined trailer.

Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), August 6, 1936, page 6.

When he pulled into Palm Springs with the trailer in 1938, a local reporter alluded to its large size by referring to it as a “dreadnought” and naming it the “Queen Mary,” after the then-new Queen Mary ocean liner. When informed that the interior was upholstered in white kid leather, the reporter exclaimed, “If true - quite the ‘snazzy.’”xlviii

RV travel is not the only hobby Gillespie took up after leaving the day-to-day operations of his car wash empire. He enrolled in the University of Southern California film school. He is behind the camera in this image of a student film production at USC in 1933.

A production scene during the filming of “The Pledge’s Plight,” a recent photoplay creation of the University of Southern California Cinema Club. Notice the use being made of reflectors to cast light into too-deep shadows. The man behind the Filmo 70-D Camera is B. K. Gillespie, a retired business man who is so enthusiastic a movie maker that he owns practically everything in the Filmo line and, when this picture was taken, was attending the photographic school at the University.

Bell & Howell Filmo Topics, Volume 9, Number 2, Summer 1933, page 3.

The Gillespies had their camera equipment with them on an RV trip to the Northwest, with plans to take “pictures of the mountains, streams and backwoods peoples of the northwest.”xlix But “three cameras and a number of lenses and other photographic accessories valued at $2,500” were stolen from the trailer while they were parked in Vancouver, Canada. No word on whether they recovered any of it.l

B. K. Gillespie died in 1945; his wife in 1972. They were both interred in the Greenwood Memorial Park, San Diego.li

An article published in 1927, following the initial success of Edler’s car wash business, described him as a “former Los Angeles school boy.”lii It’s true that he had once lived in Van Nuys during his childhood, but he had also lived in several other places. His father was a well-known scammer who moved from place to place after each of several crises brought on by his own doing, and miraculously, before the information age, he always seemed to land on his own two feet again, regardless of his shady past. The Los Angeles Times described the elder Edler as a “Poet-Doctor-Lawyer-Financier.”

Vernon Edler’s father, August Benedotte Edler, was born in Utah in about 1871 to a Swedish father and Danish mother. He was trouble from an early age. In 1889, he was arrested for literally stabbing someone in the back three times during a political squabble. He was admitted to the bar in 1894, and figuratively stabbed his own mother in the back in 1896, absconding with $300 after fraudulently transferring her home to his name and mortgaging the property for $400.liii A warrant was issued for his arrest, but the charges may have been dropped, as he continued working as a lawyer. Perhaps his mother forgave him, or wanted him to start off his married life on strong financial ground. Days after reports of the alleged embezzlement and disappearance, he was married to Isabelle Maggenetti - “The mother of the groom, who caused his arrest a few days ago, on the charge of defrauding her of a piece of property, was present.”liv

A. B. Edler’s passion for politics continued after his initial brush with the law. He was active in local Democrat party politics in Salt Lake City during the 1890s and the Social Democrat party in 1900,lv and by 1902, was active in the Socialist Party.lvi He represented striking miners during the Carbon County miners’ strike of 1903, during which time he was arrested for criminal libel.lvii He may even have represented the labor activist, “Mother” Jones, during the affair.lviii

Despite the arrest, Edler was later offered an appointment from the state of Utah to be the official reporter of decisions of the Supreme Court of Utah. He complained about a statutory cut in his wages in 1908, and left Utah in 1909 - but not without being surrounded by scandal. He may have been innocent of wrongdoing (this time), but it didn’t look good.

Shortly after Edler left town to move to California, a new tenant in Edler’s old rooms died of arsenic poisoning. Edler had lived in separate apartments in a home he shared with his mother. When Edler left, his wife gave all of her kitchen supplies to her mother-in-law, who did not bake. Edler’s mother, in turn, some the hand-me-down kitchen supplies to the new tenants, including a container believed to be “baking powder.” The wife made some dumplings, and her husband died. An autopsy showed the death to be due to arsenic poisoning, and an investigation discovered arsenic in the “baking powder.” In the end, it was determined to have been an accident, but at the time, it appeared that Edler may have been plotting to kill his mother, who had recently refused to sell her home at the request of her son.

A. B. Edler, now in Escondido, California, became a chicken rancher, poultry financier, and forger of land deeds. He was twice arrested for fraud in 1912, and others of his frauds remained undiscovered for many years. But somehow, even after all that, he got himself admitted to the bar in California. They lived for a time in Van Nuys, earning for Vernon the name of “former Los Angeles school boy,” and later in Fresno.

Vernon Edler’s name first appears in newspapers in Fresno, as an amateur actor and as the manager of a bakery in 1917. He was employed by the Bean Sprayer Company the following year, soon making a name for himself, and leaving the company to sell Bean products as an outside salesman.

By the mid-1920s, Vernon Edler had helped establish the car wash sprayer market in Los Angeles. He partnered with Wilde and Gillespie to open the first large-scale, “semi-automatic” auto laundry in Los Angeles, and later sold auto laundry equipment under his own name. He was so successful that the Bean company bought him out, and he became an executive with the new company.

In 1929, the Bean corporation, reorganized as Food Machinery Corporation, acquired the Vernon Edler Corporation and several manufacturing companies. Unlike the other companies involved in the deal, Edler was not a manufacturer, merely a a distributor for Bean products. The only assets listed for his company in a report of the deal were his “auto laundry patents.”lix