“To the victor go the spoils.”

“History is written by the victors.”

To the extent these maxims are true in global political history, they may also hold true along the trivial margin of pop-culture history. Case in point - paper cups. Dixie Cup won the battle for paper cup market supremacy, and the history of Dixie Cups, specifically, is frequently given as the history of paper cups, generally. But Dixie Cup is not the whole story - close, but there were predecessors and contemporaries who made significant contributions to the technological and marketing success of paper cups.

Most sources say that Lawrence Luellen invented paper cups in Boston, based on his earliest-filed paper cup patent,i which was filed in May of 1908 and issued in July 1912.ii At about the same time, Luellen and his brother-in-law, Hugh Moore,iii created the first of a succession of predecessor companies, which would become the Dixie Cup Company more than a decade later. It’s presented as though Luellen woke up one day and decided to invent a paper cup and the rest is history.

But even on its own terms, Luellen’s cup patent does not claim to be the first paper cup. His first-filed paper cup-related patent (filed in April 1908iv) is for a vending machine, not a paper cup, and it describes the cups used as the “ordinary frusto-conical type and of some light material such as paraffin or other waterproof paper.” And his earliest paper cup patent stresses that “the method of making” the cup did not play a part in the invention. If the cup had been new, he would have had to explain how to make it.

The only distinctive thing about his cup was an “an annular flange” or “a continuous flange” at the lip of the open end of the cup, as described in his first-filed vending machine patent and his earliest paper cup patent, respectively. The flange played a functional role in his vending machine, providing a point of leverage for the vending machinery to separate the last cup from the stack for delivery to a customer.

Luellen may have invented a specific form of a cup that could be used in his vending machine, but he did not “invent” the paper cup. In fact, when his cups first hit the market in the spring of 1909, there were already “half a dozen forms of drinking cups on the market.”v

Four years earlier, for example, the “Aseptic Drinking Cup Co., Boston, distributed samples of their ‘aseptic’ drinking cup in envelopes, the cup being made of paraffined paper and claimed to be ‘germ proof, cheap and compact.’”vi Those cups, designed by a man named John J. Shea, were sold flat, in envelopes, and could be unfolded for use, refolded and saved in the envelope for later use. The cups were also sold to the public later that year, and widely marketed over the following few years. And in 1907, the Union Paper Cup Company (organized in 1905) could churn out 2,000 paper cups a day, using paper cup manufacturing equipment patented by Henry R. Heyl, who also invented the stapler and the “Chinese” takeout container. The cups, patented by James C. Kimsey, were frusto-conical, tapered and stackable, like a standard paper cup. (Note: “frusto-conical” is a fancy word meaning, like a cone, but with the pointy end cut off - in other words tapered with a flat bottom - a standard paper cup).

To be fair, it’s not Dixie Cup’s fault that their founders get more credit than they deserve. The history of Dixie Cup Company is well documented by the “Hugh Moore Dixie Cup Company Collection,” held by Lafayette University, Easton, Pennsylvania. The history of the company as told through the collection appears to be a true and accurate history of the Dixie Cup company.

Other sources, however, mischaracterize their history as the history of paper cups in general, naming Luellen the “inventor” of the paper cup. Doing so gives him too much credit. It also overlooks the contributions of earlier paper cup pioneers, like Shea, Heyl and Kimsey, and ignores innovations by contemporary competitors, like Henry Nias, who developed Lily Cups, and Harriet Hill, who developed Tulip Cups.

Luellen deserves much of the credit he receives, but not for inventing the paper cup. He received patents in all three general classifications of paper cups (two-piece, one-piece pleated, and one-piece conical), but he was not the first in any of those categories. His true genius was in developing the dispensers and vending machines that made paper cups convenient and profitable. Luellen’s dispensers and vending machines accelerated the widespread adoption of paper cups.

Since in the 1890s, health authorities had been advocating the use of individual paper cups to stop the spread of disease, even suggesting the use of paper cup vending machines. At the time, it was typical to have a tin cup on a chain at public water coolers or other drinking water sources, which was shared by anyone and everyone who needed a drink.

But change was slow. And even as the public became more generally aware of the dangers of germs and other hidden dangers lurking in the shared drinking cup, the lack of a practical alternative made imposing change difficult. The availability of Shea’s collapsible paper cup after 1905, and the manufacturing capabilities of the Union Paper Cup Company at about the same time, did nothing to change the situation. People who wanted them could get them, but they were not easily available at the water source.

Luellen’s machines appear to have changed the equation. Shortly after his vending machines, dispensers and cups were available, state after state started banning the use of common drinking cups on railroads and in other public places. The first state to impose such a ban was Kansas, Luellen and Moore’s home state, where their contacts may have helped grease the skids.

Once the Kansas domino fell, it triggered a wave of similar laws and policies by other state and local governments, as well as private industries, to do away with the public drinking cup in favor of individual paper cups. And frequently, if not usually (at least in the early days), when government agencies or companies announced the ban, they specifically adopted Luellen’s system. Several competitors soon threw their hats - or cups - into the ring, but it was the Luellen’s vending machines, dispensers and cups that created the market, by making it convenient and profitable to provide paper alternatives where they were needed. For that he should get credit - but not for “inventing” the paper cup.

Pre-History of the Paper Cup

Paper cups were apparently known in China more than two millennia ago,vii although the use does not appear to have been continuous, and did not directly influence the modern development and use of paper cups. The modern invention of paper drinking vessels in Europe and the United States began with fits and starts, but does not appear to have developed into a full-fledged industry until about 1905.

Paper cups were reported in Germany as early as 1863.

The Mercure Aptesien states that a German has just invented paper cups, which may be used for drinking the hottest liquors, and the cost of which is only one centime!

The Newcastle Daily Chronicle and Northern Counties Advertiser, May 8, 1863, page 3.

They reportedly used paper plates in Germany two decades later. A report about German paper plates published in American newspaper suggested the possibility of using paper cups as well,

to enable a to-go cup of coffee.

Paper has gone into use in some of the restaurants in Berlin, as plates for dry or semi-dry articles of food. There is no reason why cheap paper cups, properly glazed should not be employed at railroad stations, so that passengers could take a cup of coffee along with them, instead of hastily drinking it at a lunch counter.

The Daily Cairo Bulletin (Cairo, Illinois), December 11, 1881, page 4.

A few years later, humorous commentary about the many new uses to which paper had recently been put imagined a world with even more new paper products - including paper cups. If The Graduate had been written a century earlier, perhaps Benjamin would have been encouraged to go into “paper,” instead of “Plastics!”

But the end [of the Paper Age] is not yet. We are, in reality, only just entering upon the border, so to speak, of the genuine paper age. In a few short years, in our paper shirts and paper trousers, we shall sit down to our paper tables, upon our paper chairs, and drink our coffee out of our paper cups and eat our eggs with paper spoons. . . . . - New York Herald.

The Abbeville Press and Banner (Abbeville, South Carolina), October 28, 1885, page 5.

Meanwhile, they were already using “paper cups” to serve “ices” in England, although perhaps not for beverages.

Western Mail (Cardiff, Wales), July 11, 1874, page 4.

Europeans were not the only ones making paper vessels of one kind or another. Paper “milk pails and water pails” were advertised for sale in the United States as early as 1872.

A New York firm advertises paper milk pails and water pails - in short a very large variety of household utensils made from paper, and we can readily believe they are light, convenient and artistic, and not liable to “go to staves,” or to break when let fall by the “hired help.”

Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), November 7, 1872, page 2.

In 1876, John Stevens filed for a patent on an “Improvement in Dies for Pressing Paper Vessels” (US203670; filed June 1876, granted May 1878). The invention related to “open vessels, such as wash-basins, milk-pans, &c., from pasteboard.” These products do not appear to have been designed for drinking, but it does show the early use of paper for vessels intended for use with liquids.

The year 1876 was the same year in which another, now-famous, “water tight” paper product was first patented - the folded “Chinese” takeout container. See my earlier post, “Chinese Food, Staplers and Oysters - Unboxing the Mani-fold History of the ‘Chinese’ Takeout Container.”viii

In 1881, Alphonso G. Williams patented “a new and useful Improvement in Paper Bottles” (US250469). The so-called “bottle” was rectangular, and likely more like what we might call a carton today. It was said to be designed as a “receptacle for liquids or solids or dry substances, such as baking and other powders.” The claimed advantage of paper bottles was that a “bottle of this class is lighter than and cannot be broken as easily as one of glass, and is cheaper than glass, wood, or tin.” Williams did not invent the paper bottle, but made improvements. His claimed improvement related to a “thicker paper-board top” with an opening to receive a stopper.

By 1887 , the American Paper Bottle Company, with offices in Chicago, New York and London, was making and selling “paper bottles” for “ink, blacking, dyes, paints, polish, blues [(laundry whitener)], gum, sanitary and disinfecting preparations, and numerous other objects.” Their business appears to have been built around patents granted to Levi H. Thomas of Chicago, Illinois.

Levi Thomas was a medical doctor, serial inventor and entrepreneur. He was born in Vermont in about 1836.ix He received his medical degree from Castleton Medical College in 1859,x and set up a practice in Waterbury, Vermont. Thomas built a better bear trap, receiving a patent for it in 1865 (US49174). The trap was of the classic “bear trap” style that opens into a circle and closes onto the leg. His version had a levers designed to make it safer and easier to set the trap.

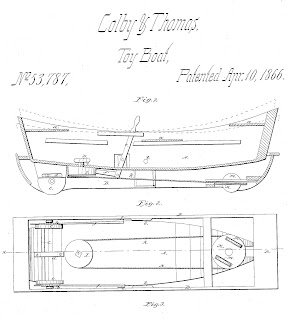

Levi Thomas and a partner patented a “toy boat” in 1876 (US53787). The “boat” was a child’s riding toy. The boat was mounted in a base painted to look like water, and rocked when propelled, to mimic the movement of a boat on water. It could be propelled by a set of “oars” attached to a ratchet-and-pawl mechanism that moved a set of wheels.

In 1880, the United States Census listed Thomas him as a “manufacturer of ink,” living in Chicago. He was the assignee of an 1883 patent to a man named William Auble, for a metallic ink bottle, with a protective inner coating to prevent corrosion caused by contact between the ink and the metallic housing (US286893). Thomas’ own variations on that patent would become the foundation of his American Paper Bottle Company, which would make a variety of “paper bottles,” precursors to paper cups.

Levi’s contribution was to substitute paper for metal, and providing the paper interior with a “water proof” coating. He received two patents on the very same day in 1885; one for a paper shoe polish bottle with a water-proof lining and paper bottom (US331842), one for a tubular paper ink bottle with a protective, water-proof lining with a bottom “of wood or other rigid material” (US331843), and a third for a “package for laundry blueing,” of similar construction, but with water-proof interior coating and a paper bottom (US331844). The two patents with paper bottoms would easily have served as a paper cups, if the tops were left off and if the market had recognized the value of disposable paper cups.

The selling-points for all of these inventions were lower costs of manufacture, lighter weight, and less likely to break than the glass, metal or wooden alternatives. The inventions appear to have been successful. A third patent to a man named Crowell, issued in 1887 for a machine to apply the water-proof coating to the interior of the bottles (US360952), was assigned to the “American Paper Bottle Company of New York,” although the company also had offices in Chicago.xi

The American Paper Bottle Company also sought entry into international markets. When they organized the Paper Bottle Company Limited in England that same year, they touted “Thomas’s Patent.”

THE PAPER BOTTLE COMPANY LIMITED

(THOMAS’S PATENT).

Extract from the Times of May 7th 1887.

“PAPER BOTTLES. - A novel and important industry has of late sprung up in Chicago, whence it is spreading to other parts of the United States; and is now being introduced into England. This is the manufacture of paper bottles by a process which is the invention of Mr. L. H. Thomas, of Chicago. These bottles are unbreakable,and of various shapes and sizes suited to the requirements of the trades and manufactures using such articles. They are produced very much more cheaply than the ordinary bottles made of glass, stoneware, or tin.

The Leeds Mercury (Leeds, England), July 15, 1887, page 1.

The American Paper Bottle Company had an exhibit at the Centennial International Exhibition at Melbourne, Australia in 1888.xii

The company later added a paper lamp body to their line of products, which was also invented and patented by Levi Thomas in 1889 (US403400). The burner and lamp were of conventional metal and glass, mounted on top of a paper fuel container. It was said to be cheaper, lighter and less likely to break. Despite the promising start, the company was dissolved in 1891, with all of the patents and machinery sold at public auction.xiii

Levi busied himself with other businesses as well. In 1888, for example, he patented some sort of fastener for a necktie. And he eventually returned to the ink trade, as director of the Safety Bottle and Ink Company of Jersey City, New Jersey.xiv He received a patent for his first “safety” ink bottle stopper in 1895. The stopper, intended for use in any ink bottle, had a perforated diaphragm through which a pen tip could pass to get ink, while minimizing the likelihood of spilling ink.

So-called “safety ink bottles” were apparently one of the great, yet overlooked inventions of the age.

Safety Ink Bottles.

The great inventions of the present age have been of such tremendous application and importance that progress along lesser lines has escaped the notice of many of the public. One invention of this character which is of great benefit but is confined to a smaller use is a safety ink bottle. This invention consists of a shallow ink rubber stopper, perforated at the base and open at the top. This is so simple that a person looking at it would wonder why it had never been thought of before. This ink bottle is non-spillable, preventing any danger from upsetting; it provides the least space exposed to air, thus preventing loss by evaporation. These bottles are manufactured in various styles, with different styles of tops, and placed on desk stands of convenient and suitable size, and sell more reasonable than ordinary ink wells. Paul’s Safety Ink wells have been adopted by the Federal and State Government departments and all the leading corporations. They are manufactured by the Safety Bottle and Ink Company, Jersey City, N. J.

Geyer’s Stationer, Volume 33, Number 794, January 23, 1902, page 23.

Again, despite apparent initial success, his investors (including the banker August Belmont) sold the company off as a going concern in 1903, to recover an outstanding debt.xv

There was more progress made during the 1890s, involving two of the three general types of paper vessels, the one-piece pleated and two-piece, frusto-conical cup (“two-piece” refers to the use of two pieces of paper - one for the sides, and one for the bottom). In 1889, for example, John L. Colhapp patented a pleated paper pail from a single piece of paper. Remove the bail from this paper pail and whadya got? - but an over-sized paper cup.

In 1891, Matthew Vierengel of Brooklyn, New York, patented a “machine for making plaited boxes or similar articles.” His machine formed a circular piece of paper into a pleated “box,” with most of the hallmarks of a modern pleated paper drinking cup.

United States Patent 463849, M. Vierengel, November 24, 1891 (filed September 30, 1889).

The patent did not describe the use of such “boxes” for drinking, and that may have been the furthest thing from the inventor’s mind. Nevertheless, nearly twenty years later in patent litigation related to Luellen’s patents, a court cited Vierengel’s patent in finding non-infringement of Luellen’s cup patent.xvi The United States Circuit Court for the Second Circuit agreed with the lower court’s ruling, holding further that Luellen’s patent was not valid, for lack of inventiveness.xvii

In 1896, Hervey Dexter Thatcher, of Potsdam, New York, invented a large paper vessel to carry something to drink, and for reasons similar to those that would ultimately motivate the development and marketing of paper cups - hygiene. It was not, however, designed for single-serving portions. Thatcher intended his “paraffined pail” (US553794) for home milk delivery, providing cheap, uncontaminated, single-use containers for milk. Single-use paper milk pails were intended to avoid the danger of contamination from poorly washed multi-use containers. Without its paper lid, Thatcher’s pail was essentially a giant paper cup of the two-piece tapered variety.

United States Patent 553794, H. D. Thatcher, January 28, 1896 (filed June 24, 1895).

The transportation of milk from the producer to the consumer in a manner which shall avoid contamination has heretofore been very imperfectly accomplished. The glass jar is an improvement over the old delivery systems; but its aggregate weight makes transportation between the producer and consumer expensive. There is also a constant loss arising from frequent breakages and failure to return the jars when emptied. The most serious objection, however, is that the glass jar is not sanitary. The glass vessel in which milk is to-day delivered to an untidy family, or to one in which sickness prevails, may to-morrow carry infected food to a healthy child in a home where every sanitary law is carefully observed.

US Patent 553794, H. D. Thatcher, January 28, 1896 (filed June 24, 1895).

In 1899, Will Kinnard, of Dayton, Ohio, patented an open-ended “Paper Vessel” in “the form of an ordinary pail, which shall be cheap to manufacture, strong to endure wear, and tight to prevent leakage.”

United States Patent 634644, W. M. Kinnard, October 10, 1899 (filed January 3, 1898).

The technology and idea of paper cups were in place before 1900. All that was needed was market motivation to resize the existing products and make small, single-serving paper cups. The motivation came in the form of recommendations by respected health authorities, and later government mandates, especially the ban on the common, shared tin drinking cup available at most public water sources at the time.

Hygiene

Although early suggestions of paper cups stressed convenience and cost considerations, the primary consideration that spurred the development and widespread use of paper cups was a growing awareness of the benefits of good hygiene in fighting the spread of infectious disease. Prior to the hygiene movement in the early 20th century, shared drinking cups were common in public areas and on public transportation. Shared drinking cups caused more problems than just the spread of disease.

New Orleans Picayune: An exchange says ice-water must be sipped slowly. That is what makes twenty thirsty people mad around the water-cooler in a hotel office where there is but one drinking cup. Sipping ice-water slowly when a lot of bigger men are saying “Hurry up!” is not healthy.

The Austin Weekly Statesman (Texas), August 4, 1887, page 8.

A story about two women holding up the line at the common water cooler, with a shared drinking cup, illustrated a similar situation. On the Staten Island Ferry, a line of sixty-two men supposedly formed behind two women who took their time deciding who should drink first, how much they should drink, and how quickly.

. . . “Oh, here’s our boat - hurry up or we’ll get left!” and then the dear creatures left the tin cup swinging at the end of the chain and rushed for the gate.

Then that crowd of men fought with one another, and surged around that water cooler, and those who were not too far gone with thirst made remarks short but deep’ and perhaps a quarter of them managed to get a drink before the boat started. - New York Tribune.

The Sunday Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), September 9, 1888, page 3.

A couple decades later, common drinking cups would be banned in many places and on some trains. If a traveler needed a drink of water and was not traveling with their own cup, they were out of luck - no more common drinking cup. The resulting difficulties illustrate the need for having cheap paper cups available as an alternative, and demonstrate how and why the market for paper cups grew so rapidly after the introduction of cup dispensers and vending machines. But apparently not everyone got the memo. An old-fashioned doctor wrote a letter to the editor to complain about the new laws.

Doctor Layton of Atchison writes to the Globe: “I was sadly reminded of the inconvenience of having no common drinking cup on a train as I came from Salina a few days ago, when an excursion, a train load of hot and thirsty people, a dozen or two of whom stood around the water cooler in the train in vain endeavors to quench their thirst; crying children were there, also, wanting water, all on account of the foolish fad of some highly imaginary doctors. What next? I suppose the hotels and depots will come next with their ‘no drinking cup,’ as well as ‘every man can furnish his towel at hotels.’ Well, in the case I saw of the trainload of excursionists, one young lady put her mouth under the faucet of the water cooler and turned the faucet; others did the same, until some one took off the water cooler lid, held it under the faucet, drew it full of water and passed it around, and all took a drink. How much better was that than a general drinking cup? Shall people suffer for want of water? Is that less deleterious to our health? We are too much inclined to ‘strain at a gnat and swallow a camel.’ I could tell your readers what causes more disease than all the flies put together, and there would be no high-spun theories about it, either, if I wished to. Let us be clean in the matter of water and food, but for heaven’s sake let us use some ‘good hard sense’ with our fads.”

Barbour County Index (Medicine Lodge, Kansas), September 8, 1909, page 8.

An editorial cartoon from 1913 illustrates a growing public awareness of the hidden dangers of microscopic bio-organisms.

|

| Buffalo Enquirer, April 8, 1913, page 4. |

Agitation for change had begun years earlier. In 1900, the International Railway Surgeons’ convention approved hygienic suggestions made by a Dr. Hurby, and some railroads had already agreed to comply. One of his suggestions was the use of “individual paper cups.”

They call for the removal from passenger cars of plush coverings, carpets, boxes over steam pipes, carved work, slat blinds and all other materials, fittings and ornaments that are likely to catch or disseminate disease germs. Doctor Hurby said unpleasant things, too, about the tin drinking cups used by everybody, and advocated providing individual paper cups.

Kansas Agitator (Garnett, Kansas), November 2, 1900, page 8.

The national meeting of the American Public Health Association followed suit, adopting a similar list of recommendations. Their suggestions also included paper cups and paper cup vending machines. The fact that the suggestions seemed radical or dubious at the time highlights how much the understanding of now-normal health and hygiene habits have changed. The editors appear to have been a little skeptical.

At the recent meeting of the American Public Health Association at Indianapolis the subject of sleeping cars received much attention from the physicians present.

From what was said, it appears that travelers in sleeping cars run bout as much danger as soldiers in battle.

The first paper presented was by Professor S. H. Woodbridge of Boston, which was the report of the committee on car sanitation. The following recommendations were reported in the paper:

. . . (6) The cleaning of cars should be frequent and thorough. (7) Floors and sanitary and lavatory fixtures should be frequently treated with a disinfecting wash. . . . . (10) Water and ice should be obtained from the purest available sources. The use of tongs in handling ice should be insisted upon. (11) The water tank should be frequently cleansed and periodically sterilized with boiling water or otherwise. (12) The public should be educated to use individual cups. Paper parafined cups might be provided by a cent-in-the-slot device. . . . (14) The filthy habit of spitting on car floors should be dealt with in a manner to cause its prompt discontinuance. It should be punished as one of the most flagrant of the thoughtless offenses against the public right to health. (15) Station premises should receive attention directed to general cleanliness of floors, furnishings, air, sanitaries, lavatories, platforms and approaches, and should be plentifully supplied with approved disinfecting material.

The San Francisco Examiner, January 19, 1901, page 22.

Despite these early pronouncements, little changed over the following eight years. In 1909, however, Kansas became the first state to enact a ban on public drinking cups, with Michigan, Mississippi following close on its heels, and New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania close to enacting bans by the end of the year.xviii

One of the chief proponents of the ban was also one of the people most likely to profit by the widespread adoption of the scheme; Lawrence Luellen’s brother-in-law and business partner, Hugh Moore.

New York, Dec. 21. - The anti-public drinking cuppers are the very latest in the way of reformers. Hugh Moore, of 115 Broadway, is at the head of the movement, and he declared today that the crusade is rapidly becoming national in extent. “One public drinking cup,” asserted Mr. Moore, “spreads more disease in an hour than a board of health can eradicate in a year.”

. . . The little public cup, the cup of our fathers, the innocent cup to be found in all waiting rooms and public places, is filled to the brim with liquid death, although it contains nothing but water, plus a few million germs, microbes, bacilli and other wiggles which are according to Mr. Moore and many physicians and health authorities, most prolific mediums for the spread of disease and pestilence, contagion and death.

Webb City Register (Webb City, Missouri), December 21, 1909, page 1 (wire story, widely circulated).

Moore and Luellen were said to have been inspired by a fellow Kansan, Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine, a pioneer sanitation crusader and head of the Kansas state board of health, the man behind the public drinking cup ban. Crumbine is frequently credited with “inventing” or naming the “fly swatter” in about 1905. Like Luellen, however, he gets more credit on that score than he deserves. A man named Robert Montgomery received a patent for a “fly killer” in 1900 (US640790) that looks exactly like what would now be called a “fly swatter,” and the expression, “fly swatter,” appears in print as early as 1900 in reference to fly killing devices.

Whether inspired by Crumbine’s sincere concern with health, or the money to be made by filling a newly perceived need, Moore and Luellen combined their talents to bring convenient paper cups to the masses. They were not the first out of the gate, however. They were beaten to the punch by John J. Shea and James C. Kimsey.

Both Shea and Kimsey had relevant paper cup patents and manufacturing facilities in place before Luellen filed his first paper cup-related patent. Shea had patents for two general types of cups, the smooth-sided, tapered style and the single-sheet, pleated style. Kimsey had patents on two-piece cups. And Henry R. Heyl had already invented and built the machines to mass produce Kimsey’s cups.

Shea introduced his cups in 1905 and was mass-marketing them by 1907, years before Luellen’s first filing. And by 1907, the Union Paper Cup Company, organized in 1905, was using Heyl’s machines to make James Kimsey’s paper cups, with a capacity of 2,000 cups a day.

Early Paper Cups

With public health authorities advocating the use of individual paper cups as early as 1900, the stage was set for changes in hygiene practices. It was only a matter of time before someone, anyone, would invent and successfully market a paper cup. Several people tried to meet the demand.

John J. Shea

John J. Shea was a medical doctor from Beverly, Massachusetts. He was on the staff of Beverly Hospital and served on the Beverly Board of Health. Shea held several patents. Most of his patents were related to paper cups. One of his early patents was for a “paper bottle” intended for milk delivery. Paper cups of his invention were in production and offered for sale as early as 1905, four years before Lawrence Luellen sold his first cup.

Shea’s earliest-filed paper cup patents was for a pleated cup formed from a single blank of paper. It were designed to fold flat for convenient storage. The idea was that you might carry one or several cups in a vest pocket, which could be removed, unfolded and used, then discarded or refolded for reuse by the same person. Although the body of the cup was formed from a single piece of paper, it could be strengthened by folding a “separate strip e” over the lip of the cup.

The bottom b of the vessel is of elliptical shape and constitutes the central portion of the blank, the bottom being preferably folded along its major axis, as shown at 3, to retain the bottom in a bulged or convexed position or to permit it to be folded inwardly within the circular wall, the bottom extending upward on the side at either end, creases 4 4 being formed at the point of connection of the circular wall with the bottom.

US772258, John J. Shea, filed September 29, 1903, issued October 11, 1904.

Shea’s second-filed paper cup patent was for a cylindrical, smooth-sided cup, formed from a single paper blank, with a wire rim for added support; the wire could be extended to form a cup handle. It was also designed to be folded flat for convenient storage between use.

This invention relates to improvements in aseptic drinking-cups; and it has for its object the prevention of the spread of diseases caused by promiscuous use of ordinary cups at public drinking-fountains, hospitals, public conveyances, &c. It is intended to be used but once or by the same person and then destroyed. When not in use, it may be folded flat and carried in the pocket, preferably inclosed within an envelop, card-case, or suitable closing device.

US759029, John J. Shea, filed January 16, 1904, issued May 3, 1904.

Paper cups according to this second patent were widely advertised for sale as early as 1905. They were sold by the Aseptic Drinking Cup Company, a Maine corporation with offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the same city where Moore and Luellen lived and worked in 1908.

Evening Express (Portland, Maine), April 12, 1905, page 2.

Washington Post, July 1, 1905, page 12.

Colliers, Volume 37, Number 16, July 14, 1906, page 26.

Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), September 17, 1908, page 7.

PURIFOLD

Aseptic paper

Drinking Cups

There’s often danger in drinking from public cups.

In traveling be sure to have a Purifold Cup.

Can be folded up after using and replaced in small envelope.

Price for one in envelope 5c

Price for two in pocket case 10c

The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), June 22, 1911, page 6.

For the budget-conscious shopper, the reusability of the PURIFOLD cup was apparently one of the selling points.

For School Children.

Purifold Aseptic Paper Drinking Cup. This is not a cheap paper drinking cup to be used once only, and then thrown away. Use with a little care it will last many weeks.

Every school child should have them. Two for 5 cents at SNIDER’S.

The Selma Times-Journal (Selma, Alabama), October 19, 1913, page 3.

The “Burnitol” manufacturing company mentioned in one of these advertisements was part of the Aseptic Drinking Cup Company, not a rival company. “Burnitol” was a registered trademark of the Aseptic Drinking Cup Company.xix

BURNITOL became a leading brand-name for another type of paper vessel, sorta the opposite of a drinking cup, the “sputum” cup - the name suggesting the ability to burn the entire container and its contents, to prevent the spread of disease.

The Aseptic Drinking Cup Company’s BURNITOL division developed their product line thanks, in part, to the wizardry of an inventor named Harry J. Potter. Harry J. Potter had a direct connection to Lawrence Luellen, magically bridging the gap between Shea and Luellen.

Potter’s paper “sputum cup” patent (US920180), filed in 1906, was assigned to the “Burnitol Manufacturing Company, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, a Corporation of Maine.” Potter’s “hospital cup” patent (US909020) was assigned to the “Aseptic Drinking Cup Company, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, a Corporation of Maine.” And, an “H. J. Potter” signed alongside Luellen’s associate, Austin M. Pinkham, as a witness to Luellen’s “cup” patent application (US1032557); Luellen and Pinkham had offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Luellen’s company, the Individual Drinking Cup Company, would later be incorporated in the state of Maine.xx Being incorporated in the same state may be only a coincidence, caused by the fact that Maine was a source of wood pulp for making the paper. But it may also be one more signal that Shea and Luellen’s groups were either one and the same, or had significant overlap in management or investors.

James C. Kimsey

James Columbus Kimsey, a native of Henderson, Kentucky, had a long career as an inventor in Philadelphia, with many of his inventions relating to paper. He patented a Christmas tree holder, several inventions related to women’s clothing and several architectural items, including a floorboard dust chute, a window, and a combined wardrobe/bathtub cabinet and a window. His paper inventions included a sheet music holder, mailing tubes and shipping tags. The shipping tags were designed as a medium to carry junk mail into the home, hidden below the address tag and revealed when the tag was removed.

In July 1903, Kimsey organized the American Paper Bottle Company, a Delaware corporation with offices on Market Street in Philadelphia, with capital of $200,000.xxi The stated purpose of the company was to “manufacture paper bottles, boxes, mailing tubes, and kindred articles.” If the name of his company seems familiar, it was the same name as Levi Thomas’ long-defunct paper ink bottle company, although the two seem to have been unrelated. Kimsey’s company would soon be defunct itself, at least technically. Its voluntary dissolution, with stockholder consent, was announced in July of 1904.xxii The company apparently reorganized at some point, but its manufacturing was turned over to a company called the Union Paper Cup Companyxxiii by 1905.

Kimsey and his “paper bottles” appear to have been the subject of an article written by an environmentalist and paper skeptic in 1903.

Another raid has been organized on our mountain forests, states the Brooklyn Eagle. As if the pulp mills were not already devastating the hillsides and drying up our water supply rapidly enough a genius in Philadelphia has patented a paper milk bottle, and has ten machines which can manufacture 20,000 of these bottles each in a day. The paper milk bottle is to be made from spruce pulp and spruces grow at the top of the mountains, the very sources of our streams. . . .

The fact is that the Philadelphia man probably believes that he can make paper bottles cheaply enough to replace the glass ones that he merely uses hygienic arguments to bolster up a business proposition. This is the age of paper as unmistakable as other ages were of bronze or gold. The making use of paper pulp are being extended continually and the addition of milk bottles would be only one item of increase in the consumption. As long as newspapers continue to grow in popularity new materials for paper will have to be found. The use of wood pulp has gone far enough to show the urgent necessity of a far-reaching and effective plan for reforesting hillsides stripped to feed pulp mills.

The Altoona Mirror (Altoona, Kansas), September 28, 1905, page 3.

Others gave his work a more positive spin.

Consumers of milk who have come to appreciate the value of purity and freedom from infection will be interested in an idea that originated in Philadelphia. . . . Some of the milk which is bottled before distribution may be injured by a lack of thoroughness in cleaning the glass receptacles after previous use. It is against that particular piece of carelessness that it is now proposed to guard by discarding the present style of bottle altogether and replacing it with another, which, like the cheap wooden plates sometimes provided for picnics, shall be used only once. . . . Dr. A. H. Stewart, bacteriologist of the Board of Health in Philadelphia, conducted a series of tests with it, and reports approvingly upon its qualities.

New York Tribune, March 19, 1905, part 4, page 1.

Kimsey received more attention for his “paper milk bottles,” but he and his associates recognized that his inventions applied generally to receptacles, vessels, tumblers, cups or any number of other applications. Some of the items described and illustrated in his patents look more or less like a modern paper cup, and he describes them as cups in some patents.

When the Union Paper Cup Company was incorporated in August 1905,xxiv its president was a man named Henry R. Heyl. Heyl had previously invented the folded “Chinese” takeout container and the stapler (see my earlier post, “Chinese Food, Staplers and Oysters - Unboxing the Mani-fold History of the ‘Chinese’ Takeout Container”). Heyl did not invent the paper cup, but he patented machinery used to make them. He was a co-inventor, with Kimsey, of machines for making “paper bottles, cups, or other containers,” for which they submitted a patent application less than a week after Kimsey filed his “paper bottle or cup” patent. The patent (US809813, filed in January 1905) described the now-familiar tapered, nested paper cups. Without the optional closure (E), it resembles a standard two-piece paper cup.

In manufacturing paper bottles, cups, or other containers for the purpose for which our invention is intended they must be cheaply and accurately made, so that they will hold liquid or other material, and yet be so cheap that the cup or bottle can be discarded when emptied. . . .

We preferably make the containers with a slight taper, as shown in Fig. 1, so that they can be nested in packing and shipping, and when desired a closure E may be used, as shown in Fig. 1.

Manufacture of Paper Bottles, Cups, &c., US809813, J. C. Kimsey & H. R. Heyl, January 9, 1906 (filed January 27, 1905).

Heyl also held cup-manufacturing patents in his own name. He specifically contemplated several different sizes, with the smaller sizes suited to be used as drinking cups.

The bottle can be of any length or any diameter desired . . . The smaller sizes can be used as tumblers.

Machine for Making Paper Bottles and Like Objects, US1018319, Henry R. Heyl, February 20, 1912 (filed October 9, 1909).

Heyl also held a patent for a water-proofing machine, a “machine for coating articles with paraffin or other coating material” (US1042914).

Machine for Coating Articles with Paraffin or Other Coating Material, US1042914, Henry R. Heyl, October 29, 1912 (filed August 23, 1909).

Heyl’s Union Paper Cup Company was reportedly set to begin large-scale manufacture of cups in 1907.

A practical demonstration of making paper cups and bottles was given recently in the plant of the Union Paper Cup company at Trenton . . . .

James C. Kinsey [(sic)] of Philadelphia is the inventor of the paper cup bottle, as it is known. . . . The patent is issued in the name of the American Paper Bottle company. The bottles are to be manufactured by the Union Paper company of Trenton. . . . The machinery for the making of the cups was designed by R. H. Heil [(sic)] of Philadelphia.

Inventor Kinsey says 2,000 cups can be turned out per hour, making 20,000 for a ten-hour workday, as contemplated.

Asbury Park Press (Asbury Park, New Jersey), December 14, 1907, page 4.

Despite their big plans and heavy investment in machinery, the business did not take off immediately. The reorganized American Paper Bottle Company and other investors sued the Union Paper Cup Company in 1908 to recover certain debts.

The Union Paper Cup plant was sold-off at auction in late-1908 for $24,950. At the time, a report claimed that “none of the patent bottles were ever put on the market although demonstrations were given from time to time.”xxv The business may have recovered a year later. In late-1909, the New York Times reported that prosperity had come to Trenton, as evidenced (in part) by the fact that “the Union Paper Cup Company has rented another factory and added more men to its wage roll.”xxvi It’s not clear what they were manufacturing at that time, but their revival coincided with Luellen’s success. Perhaps they were making cups for Luellen and his related companies by that time.

Whether Kimsey’s paper cup inventions were finally successful or not, it came too late for him to enjoy. James C. Kimsey died of tuberculosis at his sister’s home in Howell, Indiana (now a neighborhood of Evansville) in April 1908.xxvii Ironically, his condition is said to have forced him to use his own invention - a paper cuspidor (spittoon).

Messenger-Inquirer (Owensboro, Kentucky), April 23, 1908, page 2.

Lawrence Luellen

Lawrence Luellen, who is widely credited with “inventing” the paper cup, was raised in Olathe, Kansas. He apparently had a creative side and artistic talent. He wrote the “class song” for his graduating class in 1898. He sang the song at graduation in a quartet that included his future wife, Sallie Moore.xxviii Reports of their marriage four years later hinted at his inventive and mechanical, with mention of one of his earliest inventions.

Lawrence Luellen and Miss Sallie Moore were married at the home of the bride in Kansas City Tuesday. They will make their home in Boston, where Mr. Luellen is interested in the manufacture of a voting machine.

The Kansas Patron (Olathe, Kansas), January 2, 1902, page 3.

Luellen filed the first of a series of about ten US patents on voting machines in 1899. At least three of those patents were issued before the wedding. It’s not clear who or what company backed his invention, but there was apparently enough interest to bring him to Boston. Interest in his machines may have increased when the city of Boston voted to purchase voting machines.

Boston Evening Transcript, August 2, 1901, page 1.

After devoting several years to voting machines, Luellen turned his attention to women’s clothing and office furniture. Beginning in 1902, he received several patents related to fasteners for use on women’s clothing, with his wife Sallie listed as a co-inventor on at least one of those patents. In 1904, he invented an office bookcase, with recessed doors that opened upward and slid backward above the books. He did not file his first paper cup-related patent until 1908. And when he did, it was not for a paper cup, as such, but for a vending machine “for dispensing beverages or other fluids and containers therefor.” And the idea was not his, he was apparently invited to lend his talents to the project by investors interested in marketing a vending machine.

According to historians of the Hugh Moore Dixie Cup Company Collection at Lafayette University in Easton, Pennsylvania, Lawrence Luellen “first became interested in an individual drinking cup in 1907, through a lawyer named Austin M. Pinkham, who shared the same business suite on State Street in Boston.”xxix Although the statement does not claim Luellen was an attorney, it is frequently misinterpreted by those who suggest Luellen was an attorney himself.

Edwin M. Bacon, The Book of Boston: Fifty Years’ Recollections of the New England Metropolis, Boston, Book of Boston Co., 1916, page 473.

Pinkham’s signature appears as a witness on both of Luellen’s earliest paper cup-related patent applications in 1908. This was more than two years after the Aseptic Drinking Cup Company began selling Shea’s collapsible paper cups, and at a time when they were selling their PURIFOLD cup all across the country. Paper cups were already widely available, and increasingly considered important and useful. Whoever put Luellen on the job recognized the market and hoped to capitalize on it.

The Hugh Moore Collection’s history also suggests Pinkham’s investors were initially “interested in forming a company to manufacture a flat-folded paper drinking cup.” Those cups may well have been Shea’s cups. Luellen was working with the same group of people who brought Shea’s cup to market. Harry Potter, the inventor of the sputum cup assigned to Shea’s Aseptic Drinking Cup Company, signed alongside Pinkham as a witness to Luellen’s “cup” patent (US1032557).

Both inventors clearly knew one another, and may have been working for the same group of investors seeking to capitalize on the newly perceived market for paper cups. Luellen rejected Shea’s collapsible cup as not suited to use in a vending machine - the nested stack of cups was a crucial design element of the machines.

US1032557, filed May 23, 1908, issued July 16, 1912.

If Luellen had used Shea’s cups, perhaps he would have gone into business with him. But as things worked out, Luellen and Moore formed their own company, successfully launching Luellen’s cup-vending machines in 1909. The following year, Shea filed his own patent applications for his own vending machine (US1037552) and his own style of stackable cups (US1018013). Shea’s cups had little tabs extending from the lip of the cup, like little handles, which the machine used to separate the last cup from the stack and move it into position for delivery to a user, as opposed to Luellen’s machines which interacted with the outwardly bent rim of his cups for the same purpose.

Using vending machines to dispense drinking water was not a new idea. As early as 1889, the American Automatic Water Supply Company placed vending machines in cities across the country, dispensing water from the Hygeia spring in Waukesha, Wisconsin from water bottles that were six feet tall. These vending machines dispensed water, but without a cup, which had to be furnished by a user.

Boston Globe, July 16, 1889, page 2.

But they may have been ahead of their time. Despite some ballyhoo upon their introduction in 1889, there is little information about vending machines for water until Luellen and his backers entered the market a decade later.

Luellen and his associates were not the only people to see the financial possibilities of the paper cup market. An article in a magazine called The American Inventor laid out the path, even down to the collapsible cups they had first considered. Perhaps Luellen or the backers had read the article.

Cup Vending Machine.

On railroad trains and in other public places there is a need for a machine, which will automatically dispense sanitary drinking cups much after the fashion of the chewing-gum and candy vending devices. Such a device could be equipped with a supply of paper cups treated to make them impervious to moisture and compactly folded in order to place a large number in a single machine. The cup could be made without the use of glue by forming the seam on the side in a double fold and reinforced by a wire. By dropping a coin in the slot a perfectly clean cup would be delivered to the purchaser, and after it was used it would be thrown away. This scheme would give all passengers, that desired them, an individual drinking cup at a small cost. The machine would be highly popular and the device would no doubt bring a large revenue.

The American Inventor, Volume 15, Number 3, March 1906, page 72.

Luellen’s genius, perhaps, was in rejecting the folding cups that were already on the market, in favor of the nested, stacked, tapered paper cups, and having the mechanical know-how to make a machine that would dispense them one-at-a-time for a fee. His earliest patent applications were not for the cups, as such, but were for the vending machines. His patent specifications described a machine that would dispense a single cup from a stack of inverted paper cups, and deliver it upright to a customer. He also described filling the cup with water, although his patent was broad enough to cover both the single cup dispenser and the machine that would also fill it with water.

Luellen described the cups in his vending machine as “cups, of the ordinary frusto-conical type and of some light material such as paraffin or other water-proof paper” (frusto-conical is a fancy word meaning tapered sides and flat, top and bottom, like an ordinary paper cup). The text itself is ambiguous as to whether “ordinary” here applied to the shape or the use of paper for the cup. But he did not claim to have invented the paper cup, for which others have given him credit. He merely listed a type of cup already in existence that could be used in his vending machine.

The application, filed April 2, 1908, disclosed a machine that stored an upside down stack of tapered paper cups, filled the cups as it rotated the bottom cup into an upright position, and dispensed the filled cup onto a platform to be retrieved by a user. That original application became two patents. The first, for a cup vending machine (US1081508), did not issue until December 16, 1913. The second, for a beverage vending machine (US1210501), did not issue as a patent until January 2, 1917. A second application, filed August 24, 1908 and issued as a patent on January 11, 1910 (US946242), focused on the interaction of the coin and dispensing mechanism to control the vending of the cup. Although all of these patents discussed models that could dispense liquid, they also disclosed variants in which only the cup might be dispensed.

The heart of the invention was the coin-operated cup flipper. Before a coin is inserted, the bottom-most cup of a stack of cups above the device drops into position within the flipper. The lip at the top of the cup comes into play in helping separate the bottom cup from the stack. When a coin is dropped in, the handle is operated to flip the cup and drop it into the receiving platform; filling the cup as it is turned if it is a drink vending machine, or simply making an empty cup available for a user if it is a cup vending machine.

In addition to his vending machine patents, Luellen received patents in each of the three general types of paper cups, two-piece frusto-conical, one-piece pleated, and conical. His first cup-specific patent (US1032557) was filed a few months after his first vending machine patent, but did not issue as a patent until 1912. A lip at the top of the cup (“a projection which I prefer to furnish by a continuous flange 12 integral with the wall 10”), which interacted with the vending mechanism to separate a cup for the stack for delivery to a customer. It applied to any cup of this general shape, without regard to whether it was one-piece pleated or a two-piece cup.

He later added other frusto-conical cup patents, related to different ways of assembling the cup, securing the pieces together, and forming the lip at the top of the cup.

Luellen received a patent (US1308793) for a one-piece pleated paper cup in 1919, on an application filed in 1912.

In 1931, he received a patent (US1809281) for a one-piece conical paper cup. A woman named Agnes M. Klin had previously invented a one-piece conical paper cup of different construction.xxx

In addition to vending machines and cups, Luellen designed free cup dispensers - the familiar tube dispensers from which a user can grab the bottom-most cup from a stack of cups stored in the tube. Luellen filed his earliest free dispenser patent application (US1043854) in 1909 and another (US1264950) in 1912.

The availability of a free cup dispenser, as much as anything, may have contributed to the success of the paper cup. Nevertheless, in at least one round of paper cup litigation, one court found no infringement of US1043854, in part, because of the existence of an earlier “cork cabinet” of similar design.xxxi

Luellen was not content merely designing paper cups, dispensers and vending machines. Even after starting several paper cup-related companies based on his patents, he continued to pursue patents in other fields. He invented, for example, a golf tee made of clear gelatin,xxxii a “catameneal bandage” (menstrual pad)xxxiii, and a paper serving tray with “several compartments in which the various viands constituting the meal may be separately contained.”xxxiv He served as president of the Servadish Paper Plate Company,xxxv which tried to do for dishes what his other companies did for cups.

He also offered his services to government during the run-up to the United States’ involvement in World War I. He designed a system of coastal defense involving railcar-mounted mobile artillery.xxxvi

Topeka State Journal, February 12, 1916, page 4.

In 1911, Lawrence Luellen’s family were the first residents of a new housing development, which is now Mountain Lakes, New Jersey.xxxvii

Selling the Cups

Luellen, Moore and their other financial backers formed a succession of various corporate entities to manufacture and sell their products, beginning with the American Water Supply Company, followed in quick succession by the Public Cup Vendor Company and the Individual Drinking Cup Company. The Individual Drinking Cup Company sold “Dixie Cups,” by that name, as early as 1917. The Dixie Drinking Cup Company was formed by 1919, with Hugh Moore as President and Lawrence Luellen as Vice President.

Municipal Journal and Engineer, Volume 26, Number 5, February 3, 1909, page 211.

The earliest public reports of their products appeared within days of incorporation in February 1909. The Commissioner of Health of New York City installed one of the first water-and-cup vending machines.

A public spirited man in Boston has invented a very unique, simple, and practical piece of mechanism in the shape of a sanitary drinking fountain. . . . The fountain delivers for the sum of one penny, a new clean paper cup filled with pure water. The cup is made of water-proofed paper or fiver, and can not be returned to the machine, thus insuring to every purchaser an absolutely clean cup. . . .The fountain has a very neat, clean and sanitary appearance, being made for the most part of white enamel. The paper cups are stored upside down in the long nickel-plated tube just above the vendor, thus keeping them free from all dust, and therefore germless. . . . .

A water vendor of this design has recently been installed in the office of the Commissioner of Health of New York City, and the International Tuberculosis Society have determined to use it as one of their chief weapons in their battle against the extermination of the Great White Plague.

Popular Mechanics, Volume 11, Number 2, February 1909, page 138.

Within weeks, the first railroad installed one of their machines. This one, like most of their early machines discussed in print, was a cup-only vending machine, located next to a free water source. Passengers could bring their own cup, or buy one for a penny.

The Lackawanna [Railroad Company] has adopted another improvement in the sanitary line. On all first class passenger trains a penny-in-the-slot machine is placed near each ice water tank where for a penny a passenger may secure a parafine paper drinking cup for use rather than to use the public cup attached to the water tank.

Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), March 25, 1909, page 12.

Within a couple months after first use, a description and illustration of the machine appeared in numerous outlets, from Vermont to Los Angeles and Tacoma to Oklahoma.

Kentucky Post and Times (Covington, Kentucky), April 26, 1909, page 7.

Soon, other railroads adopted the system, said to be manufactured by the Public Cup Vendor Company.

Just press a little button to the side of the water tank and down comes a little wax-paper cup, absolutely sanitary. The old system of using the same cup for drinking purposes on railroad trains will be eliminated in the near future on all Great Western trains, according to contemplations now under way. . . .

Their invention dates back only two months when the first one ever used was placed on the Lackawanna road. They are manufactured by the Public Cup Vendor Co., New York. The cups are placed in a large tube near the water tank and may be reached by pressing a small button which drops a new cup for each drink of water. No using the same cup twice.

Freeport Evening Standard (Freeport, Illinois), June 16, 1909, page 10.

Other reports credited the cups to the American Water Supply Company of New England.

The American Water Supply Company of New England manufactures individual aseptic paper drinking cups which are being used on some railroads and many public places.

Physical Training, Volume 7, Number 9, September 1910, page 17.

By 1911, the Individual Drinking Cup Company of New York City was exhibiting and installing their “cup machine for use in railway cars.”xxxviii Which of the various corporate entities represented their interests, both the Individual Drinking Cup and the Public Cup Vendor companies were still in existence as late as 1916. Hugh Moore was listed as the treasurer and director of the Individual Drinking Cup Company, and treasurer and general manager of the Public Cup Vendor Company; Luellen as a vice president and director of the Individual Drinking Cup Company, and president and director of the Public Cup Vendor Company. A man named Hugh Leighton, was the president and a director of both companies. Leighton was also a director of a bank in Maine, which may relate back to other early paper cup connections with Maine, or at least the lumber industry in Maine, the source of much of the pulp used in making paper. xxxix

The sale of paper cups started chugging along when railroads and other institutions adopted the individual cup system voluntarily, but they really built up steam when state and local governments banned shared public drinking cups. The first state to take official action was Moore and Luellen’s home state of Kansas. Dr. Crumbine and the State Board of Health announced that as of September 1, 1909, public drinking cups would be prohibited on all trains and public waiting stations, as well as in public schools and state educational institutions. They made the announcement on April 1st, which may have contributed to many people not taking it seriously - at least at first.

A good many people thought the board was joking when it began talking about abolishing the drinking cups, but there is no joke to it. It is a cold fact.

The Wichita Eagle, April 2, 1909, page 3.

The cups eventually did catch on, although the transition was not always smooth.

Paper drinking cup vending machines were installed at the Union depot yesterday afternoon and attracted much attention, but did not get much pay.

The patrons of the depot looked at the machines and when they discovered that it took a penny to get a paper cup, but that they could use one of the granite ware cups tied to a chain for nothing and get the same grade of ice water, they did not hesitate.

A number of the paper cups were purchased as souvenirs.

The Wichita Beacon, September 10, 1909, page 1.

Other states, railroads and businesses soon followed suit. In addition to the penny-a-cup vending machines, some chose to install free dispensers, providing cups for free to users in certain places. In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for example, the state government placed vending machines in public places and free dispensers in office spaces.

One is a public vending machine from which everyone athirst can get a sanitary cup for a cent. The other is a similar machine, which will distribute the cups free of cost. The cent-in-the-slot type of machine is to be installed in the corridors adjacent to the public fountains; the free vending machines are to be placed in the departments for the use of the employees.

Buffalo Morning Express, May 29, 1910, page 15.

They also marketed paper cups to the medical and dental professions, and to soda fountains and restaurants.

The Texas Dental Journal, Volume 29, Number 5, May 1911, page 40.

Southern Pharmaceutical Journal, Volume 3, Number 7, March 1911, page 32.

For many years, Luellen and Moore’s Individual Drinking Cup Company sold their cups under the name “HealthKup,” for use in pay-per-cup vending machines and free dispensers.

Two Ways of providing paper cups

One Pays in Cash - Sell them from penny-in-the-slot Health Kup Vendors, 66% profit;

One Pays in Goodwill - Give them one at a time from Health Kup Dispensers 100% profit.

Philadelphia Inquirer, August 10, 1916, page 18.

Beginning 1917, they sold them under the “Dixie Cup” name.

Indianapolis News, July 26, 1917, page 9.

Philadelphia Inquirer, August 16, 1917, page 5.

Philadelphia Inquirer, August 21, 1917, page 4.

Although Luellen and Moore’s companies’ dispensers and vending machines appear to have jump-started the paper cup industry in 1909, they were not the only game in town. Several other companies created successful cups of their own design and manufactured vending machines operated by different mechanisms. Their two biggest competitors appear to have been the manufactures of the “Lily Cup” and of the “Tulip Cup.”

Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1921, page 14.

The Lily Cup and Tulip Cup were both of the pleated paper cup variety. The names were suggestive of their look - the pleats resembling petals of a flower. The primary difference between the two cups was that Lily Cups were infused or coated with wax, whereas Tulip Cups were waxless. In Lily Cups, the wax prevented the pleats from unfolding; in Tulip Cups, a rolled lip prevented the pleats from unfolding.

The similar floral theme of their names gave rise to a claim of trademark infringement, among various patent infringement claims, in litigation between the two companies in 1925. Luellen and Dixie Cup also joined the fray.

“A Rose By Any Other Name.”

Hearing was held recently in Brooklyn, N. Y., in the suit brought by the manufacturers of the Lily drinking Container Corporation. . . . In its complaint the Lily Company alleges that it has made and sold billions of drinking cups of the familiar lily design for which it holds a patent, and that the Tulip cup is so nearly identical in appearance with the Lily as to infringe the patented Lily cup. “Tulip” is a mere variation and infringement of the registered trade mark of the Lily cup. . . .

Suit has also been filed by the Dixie Drinking Cup Company, of New York, against the Tulip Company, under the patent of L. W. Luellen, who claims to be the originator of the paper drinking cup now so generally used.

National Hotel Reporter (Chicago, Illinois), April 20, 1925, page 1.

The Lily Cup was a product of the Public Service Cup Company of New York, incorporated in 1911 by Henry Nias. The Public Service Cup Company built its line of products on several patents to Henry A. House, including a “paper-plaiting device,” a “machine for making paper receptacles,” and a “drinking vessel,” filed in 1910, 1911 and 1912, respectively. Edward Claussen also held several utility patents related to cup manufacture. Claussen also designed their distinctive flared-lip shape, claimed in a design patent, filed in 1911 and issued in 1912. Henry Nias himself held a patent to a “cup dispensing device” of his own design, filed in 1911 and issued in 1913.

Cincinnati Post, April 15, 1921, page 16.

The Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 47, Number 7, July 1914, page 349.

The Tulip Cup was a product of the United States Drinking Cup Company. Their products were based, primarily, on patents to Harriet Hill. Harriet Hill held patents for a paper cup dispenser of novel design, a free cup dispenser of novel design, and a one-piece pleated paper cup with a lip folded over on itself three times. The folded lip created a stronger one-piece, pleated cup, which could retain its shape even without being treated with wax, which was one of their major selling points. Descendants of her design can be seen in all pleated paper cups in use today, like ketchup cups at most fast-food restaurants or rinse cups in many dentists’ offices, which universally have rolled lips.

Tulip Soda cups are made on the principles that made the Tulip Drinking cup famous. One piece - no bottom to fall out. The Rolled top rim presents a smooth edge to the lips and being locked does away with the necessity of using glue or other adhesives to hold it together. Therefore, there is no taste with Tulip cups. And the Tulip cup is a real cup.

International Confectioner, Volume 28, Number 4, April 1919, page 23.

Harriet Hill ran the company with her children, Willoughby F. Hill, Jr. and Herbert Hill. She would eventually preside over at least three related companies, all headquartered in New York City, the United States Paper Drinking Cup Company, the United States Paper Products Company, and the Tulip Cup Company.

Based on the records in the patent office Hill appears to have been the innovator who created the sturdy rolled edge. Reports of stolen trade secrets and a family squabble suggest that the truth may be more complicated.

In May of 1913, a man named Alexander J. Lackner sued Harriet Hill and others connected with the United States Drinking Cup Company for stealing his trade secrets. Lackner was Harriet Hill’s brother. He accused her, her sons, his brother John and a company employee named Richard Blazej of stealing his secret process for rolling the lip of a pleated paper cup, which sounds suspiciously like her patented process for folding over the rim.

Alexander J. Lackner several years ago invented a paper drinking cup with a peculiar double band at the top which does not need to be coated with wax to make it serviceable. He attempted to have it patented but was told that it was more desirable to keep the mode of manufacture a trade secret.

He engaged his brother John Lackner of the John Lackner Company to manufacture the cups and his sister, Mrs. Harriet Hill, of the United States Drinking Cup Company to sell them. Former employees allegedly learned the secret and are putting cups on the market.

Brooklyn Times Union, May 7, 1913, page 8.

A report of the case after trial describes the alleged “secret” in greater detail.

The Lackner company manufactures paper boxes and novelties at a factory in Whitestone. The most important of its products s a paper drinking cup. This has a large vogue because a peculiar turning over of the top edge in three turns which makes the cup very durable. The Lackner cup and one manufactured in England have this feature. In the Lackner cup this turn is made by a machine which has three separate dies. In the English cup the turn has to be made by hand.

Alexander Lackner, inventor of the machine, engaged Blazej on the strict understanding that he would never reveal any of the secrets that he learned in the Lackner employ. In order to keep the machine a trade secret the greatest secrecy has been maintained. The machine has been kept in an apartment into which only those who operate it have been admitted and no one operator completes an entire cup.

Brooklyn Times Union, February 3, 1914, page 8.

When the case went to trial, there was only one defendant, Blazej. It is not clear how the claims against the other defendants were resolved. It is also not clear whether the “turning over of the rim” is the same as the folded-over rim of Harriet Hill’s patent. The publication of her patent in March 1913 also raises the question of what was so secret when reports of the suit were published in May 1913. It also raises the question of whether her patented invention was the same as his claimed trade secret.

It is possible that she invented the fold, and that her brother invented the machine that did the folding. But if Alexander Lackner invented his folded rim “several years” prior to 1913 (as claimed), why didn’t Harriet Hill file her patent application until June of 1912? In any case, the patent and the trade secret litigation raises questions about the details of the invention and its inventorship.

But regardless of those questions, it is clear that Harriet Hill retained control of the technology and of the company. She also received at least three more cup-related patents, one for a vending machine and one for a free dispenser, both of novel design and working by mechanisms different from Luellen’s. The selling point of her free dispenser is that it was a paper tube, the same tube the cups were packaged and sold in, which could easily be converted into a dispenser.

Famous Tulip Drinking Cups - the cup with the rolled edge - will fill your need. They are not heavily waxed like others n the market, and therefore are not sticky and do not adhere together, causing the use of two cups where only one is needed.

Packed in Self-Dispensing Tubes

No Holder Necessary!

These are just the thing to use on picnics. The tubes these cups come in are the tubes they dispense from. They are as effectual as an expensive holder, and as durable - lasting as long as there are cups. May be attached to the wall by a nail.

Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock, Arkansas), August 5, 1919, page 8.

Years after the trade secret litigation and her earliest rolled lip patent, Harriet Hill continued innovating. She patented a new style of rolled-lip cup in 1919.

Harriet Hill died in Grand Central Station of “heart disease” (a heart attack?) at the age of sixty in 1921.

Mrs. Harriet Hill, inventor of the Tulip drinking cup machine, died recently of heart disease in the Grand Central Station, New York. She was sixty years old and lived at 301 Lexington avenue. She was formerly head of a paper products manufacturing company.

Geyer’s Stationer, Volume 71, Number 1806, June 16, 1921, page 30.

Harriet Hill did not live to see her company merge with the Lily Cup company, but her rolled-lip patent of 1919 may have paved the way for the merger. Her new patent was at the heart of infringement litigation in 1928. Her patent prevailed, and shortly afterward the Tulip Cup Company would merge with the Public Service Cup Company, the manufacture of Lily Cups.

The litigation was between Tulip Cup and a company called the Ideal Cup Corporation, but there is reason to believe that Public Service Cup and Ideal Cup were somehow related. Both companies leased space in the same building on the same day, with Ideal on the sixth floor and Public Service Cup on the seventh.xl And the president of Ideal Cup, Frederick Ruhling, would become manager of Lily-Tulip Cup Metropolitan New York territory sales division in 1929, and years later, in 1944, would be elected to the board of Lily-Tulip.xli

An advertisement offering Lily Cups and Ideal Cups side-by-side seems to support the suggestion of a relationship between the two.

The Lily Drinking Cup is made of a single circle of paper, waxed - one-piece construction prevents leaking. The triple pleat formation gives it triple strength and rigidity. . . .

The Ideal Paper Cup is non-collapsible and made of high-grade unwaxed bond paper with rolled edges, Lily cup shape.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 13, 1929, page 4.

In 1928, the Tulip Cup Company, now owned by a man named Simon Bergman, sued the Ideal Cup Corporation for infringement of Harriet Hill’s rolled-lip patent of 1919. The trial judge ruled against Tulip and in favor of Ideal. Judge Moscowitz declared that the cups were an idea, not an invention. A report of the verdict gives a sense of the value of Harriet Hill’s patent.

The cups were originated by Mrs. Harriet Hill, who sold the idea to the Tulip cup concern. Testimony in the trial showed that as many as 600,000,000 of the cups were made by that organization in a single year, the receipts for which amounted to $1,458,000.

New York Daily News, February 10, 1928.

That decision was reversed on appeal to the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

This suit is for infringement of the Hill patent, No. 1,310,698, filed November 19, 1918, and granted July 22, 1919, on a pleated paper cup having a curled rim. . . .

The reception of this cup by the public and its extensive sales indicates a preferment over other cups. The appellee has selected it because of its durability and cheapness. It has become an infringer . . . . We hold the patent both valid and infringed.

Tulip Cup Corporation et al. v. Ideal Cup Corporation, 2nd Circuit, 27 F2d 717-19.

The Second Circuit’s decision in the case was handed down on July 2, 1928. Ideal appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States, but their petition was denied in November 1928. During the interim, in October of 1928, Henry Nias of the Public Service Cup Company and Simon Bergman of Tulip met for dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City.xlii The merger was arranged before the end of the year.xliii

Whether Public Service Cup Company was directly involved in that litigation or not, the decision upholding Tulip’s rolled-lip patent may have been the paper straw that broke the paper company’s back, motivating them to merge with Tulip, the company that Harriet Hill built.

If You Can’t Beat ‘em, Join ‘em

And in the if-you-can’t-beat-em-join-em department, Lawrence Luellen received his own patent for a waxless, pleated paper cup, similar to Harriet Hill’s (or Alexander Lackner’s) in 1922. Luellen added an extra indentation to the folded-over lip for added strength. No news on whether Dixie ever faced off with Tulip or Tulip-Lily over their pleated cup.

Conclusion

Give credit where credit is due. Lawrence Luellen and Hugh Moore helped create the modern paper cup industry, but did not invent the paper cup. John Shea beat them to the punch by a few years, and James Kimsey was poised to manufacture thousands of cups a day before his premature death in 1908. And other inventors had been making paper pails, buckets and cups for other purposes for several decades before Luellen and Moore made their first cup. But the industry never really took off until after Hugh Moore started selling Luellen’s vending machines and dispensers in 1909. Their Dixie Cups would come to dominate the field.

To the victor go the spoils.

i “Cup,” US1032557, July 16, 1912 (filed May 23, 1908).

ii The filing date of a patent application is closer to the date of “invention,” because the entire invention must be reduced to writing by that date. The date of issue can be many months or years after the date of filing, and not be indicative of true first date of invention.

iii Lawrence Luellen, the named inventor on most of the company’s early patents, was married to Moore’s older sister Sallie. They all attended the same schools in Olathe, Kansas. Lawrence and Sallie were in the class of 1898 together; Hugh Moore was five or six years behind them.

iv “Vending-Machine,” US1210501, January 2, 1917 (filed April 2, 1908).

v The Topeka Daily Capital (Kansas), March 31, 1909, page 4.

vi The Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 34, Number 13, September 28, 1905, page 305. Shea distributed samples of his cup at a convention of the National Association of Retail Druggists held in Boston that year. Coincidentally, it was the same convention from which the earliest known reports of the “Banana Split” in print appeared. The standard history of the time and place of the “invention” of the Banana Split is also in dispute; a topic for a later post.

vii Joseph Needham, Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin, Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing, Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1985, page 122.

viii https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2023/02/chinese-food-staplers-and-oysters.html

ix The 1880 census lists the age of Levi Thomas of Chicago as 44.

x Burlington Daily Times (Vermont), June 28, 1859, page 2.

xi A. N. Marquis & Co.’s Business Directory of Chicago 1887-8, Chicago, A. N. Marquis & Company, 1887, page 72.