Kings of the Dudes - Introduction

Kings of the Dudes Part II - Heirs to the Throne - Onativia and Teall

Kings of the Dudes Part III - Western Dudes - J. Waldere Kirk

Evander Berry Wall

Evander Berry Wall was precisely the kind of man Robert Sale Hill had in mind when he coined the word “Dude,” he earned his money the old fashioned way – he inherited it. And although it is not true that he never worked, he didn’t work much, and spent most of his life in leisure, enjoying the fruits of his parents’ and grandparents’ labors.

When reports of Wall’s insolvency circulated in 1885, an observer commented on his brief “career” as a “Dude.”

And so passes out of our daily life one who in three years has spent a large fortune, which gave him an opportunity for a great and noble life, a life of usefulness, a life of honor, but he chose the fool’s part – and like a fool he perishes.

The Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1885, page 2.

Except that he hadn’t perished – at least not yet. By his own account, he squandered “two large fortunes” left him by his father and grandfather, “both fortunes over a million dollars each.” But he was “saved from being continually broke because a third fortune,” his mother’s “was very wisely put in trust” for him. He did not disagree with those who said he lived a “useless” life, but defended it as one “packed with interest and movement, a life of gaiety and pleasure . . . a life fuller than that which falls to most men.”i

When he did die in 1940, the columnist “Bugs” Baer gave a suitable send-off to someone still remembered, nearly six decades later, as the “King of the Dudes.”

He was headed nowhere. And arrived.

“King of the Dudes,” Arthur ‘Bugs’ Baer, Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, June 9, 1940, part 4, page 2, June 9, 1940 (King Features Syndicate, Inc.).

Wall was born in New York City in about 1859.ii Although born in his family’s home on Fifth Avenue, his mother’s and father’s families were closely connected to Williamsburg and Brooklyn. Appropriately, for the original Brooklyn hipster, his family money and name came from industries still practiced by hipsters in Brooklyn today - marijuana and liquor distilling. His father was a rope-maker who traded in hemp. His mother’s father, Evander Berry, was a partner in the Coles & Berry distillery at Ninth and Ainslie Streets, near Union Avenue.

Berry’s paternal grandfather, William Wall, apprenticed as a rope-maker under an uncle (his mother’s brother) in Philadelphia for ten years, from the age of eleven until the age of twenty-one, after which he moved to New York, saved enough to buy his own small business, grew it into the largest rope factory in the United States, founded and served as a Trustee and Vice-President of the Williamsburg Savings’ Bank, and was elected Mayor of Williamsburg (before annexation into Brooklyn) and to the United States House of Representatives.iii

William Wall’s Sons Ropewalk was located on ten acres of land along Bushwick Boulevard, between Marshall and McKibben Streets in Brooklyn. An article about the cultivation and uses of hemp accompanying a written tour of his ropewalk discusses the various types of plants used to manufacture rope, including hemp, as well as preparations of the plant for other uses, including those known by now-familiar sounding names, “Hasheesh, of Arabia,” and “Gunjah” from India.iv

William’s son and Berry’s father, Charles Wall, started his career outside the family business, in “the employment of Williams & Hinman, ship-chandlers.” But he “subsequently went into business with his father, and succeeded him.” In addition to running the ropewalk, Charles “was an officer in various insurance corporations” and “a large stockholder and a Director of the Brooklyn Ferry Company,” before the Brooklyn Bridge was built, when the ferry was a much more important and profitable enterprise than it would become after the bridge was built.v

When Charles Wall died in 1879, Evander was twenty years old, his son William (“Willie”) sixteen and daughter Louise (“Lulu”) thirteen. After his death, his wife, Eliza, remained a partner in the business, and his brothers, Frank and Michael Wall, remained active in running the company.

Charles left each of his sons $300,000 to with as they pleased. E. Berry Wall spent his money on horses and clothes. Within four years he would be “King of the Dudes.” Four years later he would be broke (or at least relatively so).

When E. Berry Wall became famous as a “Dude,” so-called “Dudes” were characterized in part by weakness and laziness. But in his late-teens, Berry had reportedly been “one of the fastest amateur walkers in the country.”

Of course we have our dudes, but divest a majority of them of their exaggerated collars and really absurd styles of dress and put them in gymnasium uniforms, and you will see that they possess well-developed biceps and forearms and sturdy frames supported by muscular limbs. Take, for instance, Berry Wall, who has been time and time again alluded to as the “king of the dudes.” He certainly looks and acts effeminately, but he has won fame as an athlete. Why, only seven or eight years ago he was one of the fastest amateur walkers in the country. He was somewhat of a dude then. His costume when on the track consisted of silk shirt and satin knee breeches, but his lungs and limbs were sound enough to enable him to walk a mile in 7 minutes and 20 seconds, and there are not many walkers who can to-day cover 1,760 yards in the same space of time at fair heel-and-toe progression. He had been famous as an athlete in his younger days and still exhibits a lively interest in contests of skill and endurance.

Frederick William Janssen, A History of American Amateur Athletics and Aquatics, with the Records, New York, Outing Co., 1888, page 60.

The characterization of his being “one of the fastest” in the country may have been an exaggeration, but he was a competitor and posted some decent times. For comparison, a man named F. P. Murray set a world record in the one-mile race-walk in 1883, with a time of about 6:30vi (the current world record is about one minute fastervii). Wall’s best reported time was nearly a minute slower, at 7:20.

In the late 1870s, Berry Wall competed in running events of the New York, Manhattan and American Athletic Clubs. A few of his race results have been found, showing times slower than his best. In April of 1878, he finished second in the “one-mile walk” in which most of the runners “were thoroughly inexperienced, and walked in a very loose manner.” The winning time was just under eight minutes. viii In April of 1879, he placed third in his heat of a handicap race, in which the winner (who was given a handicap of 40 seconds) completed the mile in 8:15, actual time. It is unclear whether Wall was slower in actual time, or merely lost after factoring in the handicaps. Wall’s handicap and time were not reported.

In July of 1878, Wall participated in a timed relay race for time with no opponents, in which his team walked two miles in just over twelve minutes; at a pace of nearly 6 minutes per mile, well under the individual world record pace at the time.ix That meet was apparently integrated, although the events may have been segregated – a field of “six colored men ran one mile level,” with a winning time of 5 minutes, 46 and ¼ seconds.

Wall came to the attention of the sporting public again at the age of 23 in 1882, this time at the horse racing track. In April of that year he shelled out $2,500 to buy a horse named Knightly King from J. B. Randall & Co. of Lexington, Kentucky.x And a few weeks later, he spent about $4,000 for a string of seven race horses at an auction of horses owned by James A. Grinstead, also in Lexington, Kentucky.xi

He needed horses to stock his new breeding farm in Lakewood, Kentucky, now a neighborhood of Lexington. A description of his new enterprise in early 1883 (months before first being labeled “King of the Dudes”) was optimistic about his prospects.

The Complete and Well appointed Breed-

ing Farm of Preston & Wall, Two Rising Young Turfmen.

Situated between the Winchester and Richmond pikes, near this city, is Lakewood, the breeding farm of Mr. Wickliffe Preston . . . .

He has associated with him in his breeding and racing venture Mr. E. Berry Wall, of New York City, a public-spirited and very wealthy gentleman, a member of the Jockey Club in New York and a great patron of racing. Should all go well and they pull together, having a fine estate and almost unlimited means, it seems that success should attend their efforts. . . .

The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), February 18, 1883, page 5.

But the farm never turned a profit, as he admitted several years later.

When quite a young man I, in partnership with Wickley Preston (son of General Preston, one time United States Minister to Spain), had thirty brood mares on a stock farm at Lexington, Ky. I produced some famous horses, notably Wallflower, who won the Tobacco stakes at Covington . . . . But the experiment was an expensive one, and I learned the lesson that a man can’t make the breeding of horses successful unless he gives his undivided attention to it. I found, too, that a stable should be continually weeded out. It costs as much to keep a poor race horse as it does to care for a clinker. I did not attend to the stock farm myself and the result was there were no profits.

The Times (Philadelphia), July 14, 1889, page 14.

E. Berry Wall spent the summer of 1883 at Long Branch, on the Jersey Shore, then a fashionable summer resort frequented by the rich and famous. His expensive dress and eccentric habits quickly attracted the attention of other guests and the press, who labeled him “Champion Nincompoop” by mid-July and “King of the Dudes” by the end of July.

THE CHAMPION NINCOMPOOP

Long Branch corr. New-York World.

Mr. E. Berry Wall has been at the West End for some little time and had caused quite a sensation. This morning your reporter arrived at the hotel just in time to see this young gentleman emerge from its portals in the gayest of bathing suits. The jacket of brown was ornamented with buttons and froggings of scarlet, loose trousers gathered at the ankle, and a jaunty little cap worn on one side completed his toilet. His hair was as carefully banged as usual, and he wore his prince-nez. He was followed at a short distance by his valet loaded with Turkish towels and a wrapper for his master to wear on his return from the water. The young gentleman’s habits are generally discussed at the hotel. It is a well-known fact that his morning meal consists of a banana and a cocktail brought into his room on a silver salver by his valet. At his other meals he eats nothing but game, plover being his favorite dish. In the evening a perfumed bath is always prepared for him. Mr. Wall changes his entire apparel several times every day, and has at present no fewer than forty five suits of clothes in his room. His tailor is Poole of London, and his shoes come from Paris, Ky. His collars could not be any higher without seriously interfering with his ears. Mr. Wall is constantly surrounded by a crowd of followers, but it is very generally admitted that he surpasses them all.

The Buffalo Morning Express, July 13, 1883, page 1.

A dispute over the bad press reportedly drew him into a duel – not a duel for the title, “King of the Dudes,” but an actual duel – “Saturday afternoon on the beach with Colt’s or horse pistols, distance ten paces.” At least that’s what was reported.

But it was all fake news, a practical joke, with each of the supposed participants deceived into believing the other was out to get him. E. Berry Wall reportedly left town out of fear of being shot, although that may have been fake news as well. He claimed he merely left for Saratoga because Long Branch was “in such deucedly bad form, don’t chew know.”

An early report of the “duel” appears to take the threat seriously – they may not have been in on the joke yet, or they were intentionally putting out fake news to sell papers. And although later “King of the Dudes” feuds and duels were supposedly intended to win the title, this one was reportedly intended to lose the title, by forcing a newspaper to stop calling him a “West-end dude” or “King of the Dudes.”

TEN PACES.

A Duel Imminent Between the “West End Dude,” Berry Wall, and Henry Nichols, Editor of the Long Branch Record.

Long Branch, July 26. – The usual tranquility of this quiet resort is sadly disturbed over the report of a duel which is said to be likely to occur in the sands next Saturday afternoon. . . . The participants are said to be no other than Mr. Berry Wall, a fashionable young man . . . and Mr. Henry Nichols, editor of the Long Branch Record.

No young man at the Branch is better known than Mr. Berry Wall. His wearing apparel is of the finest material, of the greatest variety and faultless make. His “get-up” is exquisite, and his bearing so reserved and dignified that many vulgar people have ill-naturedly termed him “The West End Dude.”

Exasperating as such a distinction was among scores of young men as well qualified for the honor as himself, Mr. Wall magnanimously overlooked it until the papers took hold of it. There he concluded the line must be drawn. Finally, when the papers dropped his name altogether and spoke simply of “The West-end dude,” Mr. Wall declared that the matter had gone far enough.

By dint of inquiry he learned that the editor’s name was Nichols. Wall’s friends told him that the editor was a small man and would prove a sure victim to Wall’s science and prowess. The outraged guest sent the editor a letter demanding an instant and a written retraction and apology. The letter has not been made public yet, but the few who saw it assert that it breathes a warlike spirit and intimates a caning or a whipping if the demands therein contained were not complied with instanter.

The reply surprised and disconcerted Mr. Wall. The small editor divining that in a contest with fists he would make a sorry spectacle, before and after a combat, seized the bull by the horns and, instead of apologizing or bending the knee, sent a defiant challenge to the guest and offered to meet him on Saturday afternoon on the beach with Colt’s or horse pistols, distance ten paces.

Mr. Wall consulted with his friends, but what conclusion was arrived at is not yet known.

Both men are actively preparing for the meeting. Each declare there will be no compromise or reconciliation; that some one is going to fall. All the rest of Long Branch is laughing, declaring it to be the best joke of the season.

The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), July 27, 1883, page 3.

The practical joke was exposed a few days later. Although the actual duel never took place, they may have had a brief confrontation on a hotel veranda, each one believing the other was out for their blood.

New York society people had a good laugh over the escapade of E. Berry Wall, one of Gotham’s gilded youth at Long Branch. He cut quite a dash there with his endless variety of clothes and horses, and at the same time acted like such a silly fool that one of the papers poked no end of fun at him calling him the King of the Dudes. Some of his friends took up the matter and sent an imaginary challenge for a duel to the editor of the paper.

Two worse scared men than the editor and young Wall could hardly be imagined. They met on a hotel veranda and said some disagreeable words to each other, like two school girls who are “mad” at each other, and then Berry, to escape further trouble skipped off to Saratoga, with bag, baggage, and horses, where he signalized his arrival by dropping $1,500 at roulette the evening on which he arrived.

Berry, to use the Anglicism, is not half bad, only he has too much money and too little brain. He is about twenty-three or four years old, and his model and exemplar is the distinguished Freddie Gebhard. About a year ago he went in for racing, but up to the present he has not done much. This spring however he bought a lot of high priced yearlings at the sales in Kentucky, and next year, that is to say, if he does not run through all his property before it, he will branch out on a large scale.

Blue Ridge Enterprise (Highlands, North Carolina), August 9, 1883, page 1.

For his part, Wall claims his departure from the beach had nothing to do with fear.

“The King of Dudes.”

Every eye, writes the Saratoga correspondent of the Albany Journal, is out for a glimpse of E. Barry Wall, yclept at Long Branch “The King of the Dudes,” who arrived at the United States [(a hotel in Saratoga, New York)] on Friday. He lounged about the piazza Friday night smoking LaFerme cigarettes, in a suit of dark clothes, a white tie and a stiff hat, a costume at once notable for elegance and inconspicuity. Mr. Wall walks slightly Spanish.xii To a friend he said he was not a victim of a practical joke at the seashore, but quitted the “beastly place, don’t chew know,” because “they were in such deucedly bad form, don’t chew know.”

The Post-Star (Glen Falls, New York), July 30, 1883, page 3.

SALTED FOR THE SEASON.

The Chilling Reception Accorded the Advances of a Susceptible Dude by Two Belles of the Long Branch Beach with a Weakness for Real Men.

A representative Long Branch “Dude,” not necessarily E. Berry Wall, but from a time when he was the most notorious “Dude” at the beach. National Police Gazette, August 25, 1883, from a Tweet by @Nymph_du_Pave, August 25, 2021. https://twitter.com/EsnpcB/status/1450518941336440832.

E. Berry Wall may have left Long Branch, but the name stayed with him. He was still “The King of Dudes” the following year, when the New York correspondent of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch who wrote New York gossip columns under the name Madison Squareman, provided more detail about the previous year’s practical joke.

THE KING OF DUDES.

Berry Wall, the Celebrated New York Dudelet.

. . . In New York, at Long Branch, at Coney Island, or at Saratoga, E. Berry Wall is facile princeps “King of the Dudes.” Clothes and horses are the two full joys of his life. He has been known to appear in six different suits on Broadway in the course of a single afternoon. He it is who has given the distinctively British stamp to the dudish affection, and he prides himself on the thoroughly English style of his clothes, his hats, his boots, his horses and his “rigs.”

Last summer he was the victim of a cruel hoax at Long Branch. He received a letter purporting to come from the editor of a local paper asking for his photograph to illustrate a personal sketch. “Berry” boastingly showed the note to several acquaintances along with a very curt refusal that he had prepared at definite pain. Some of these acquaintances formed a conspiracy, as a result of which an alleged friend of the editor waited upon the King of the Dudes with a challenge to fight a duel or retract his insolent note.

Berry was really frightened. He consulted his friends. They being in the secret, of course, urged him to fight. He did in fact, select a second and accept the challenge, but before the appointed hour discovered that he had important business in Montreal. Before he had reached Saratoga, he was overtaken by a telegram praying that he come back and all will be forgiven. It afterwards appeared that his alleged antagonist neither wrote the first note, nor knew of the challenge, and was, in fact, absent from the Branch at the time.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 13, 1884, page 13.

Several years later, Berry Wall chimed in on the matter himself.

THE ORIGIN OF HIS TITLE

“When were you first called ‘King of the Dudes,’ Mr. Wall?”

“Oh, five or six years ago, down at Long Branch. There was a newspaper man down there running a little weekly paper called the Surf, or some such name, who began attacking me and commenting on my dress, and naturally I resented it. I got into a little altercation with him on the hotel piazza one night and threw him off and then there was talk of a duel. It was all nonsense. I wouldn’t have met him under any circumstances.”

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 29, 1888, page 9.

What with his flashy clothes, fast (and not so fast) race horses, he must have cut quite the figure for a few years. But he was in the news for a different reason in 1885.

A BRIGHT SOCIAL STAR’S TEMPORARY ECLIPSE.

Mr. E. Berry Wall’s Embarrassment –

Some of the incidents in a very striking career.

Club men about town are just now discussing the financial affairs of the “King of the Dudes,” Mr. E. Berry Wall. For some time past the young man has rather withdrawn himself from the public gaze, and since the beginning of August has remained in comparative seclusion at Saratoga. Since his retirement he has transferred his running horses, with which he had some little success, to the Preakness stable, under the colors of which they will hereafter run.

While Mr. Wall has been considered as rather embarrassed for some time, it was not until within a day or two when a check of his for $22 was allowed to go to protest that the actual state of his affairs was revealed. His friends said yesterday that his follies were only those of a generous hearted man, unaccustomed to take charge of large sums of money; he was all right, and would be taken care of by his family without fail. . . .

The young man came into possession of his property, estimated at about $300,000, some three years since, and during that time has figured in the public prints both here and in Europe as a young Prince Prodigal.

The New York Times, September 5, 1885, page 1.

He may have been a nice guy, but not everyone was so generous with their assessments of his character.

Three years ago his father died, and a brainless donkey – who had never been taught to do any useful thing – suddenly found himself in possession of $300,000 in hard cash. The world was all before him; he started out to make a sensation, and he succeeded beyond his most sanguine expectations. No such gorgeous vision had ever astonished the eyes of New Yorkers before.

It was impossible to describe his dress, for he was never dressed twice alike. One morning as I stood in front of the Brunswick, Berry Wall and a half dozen friends were taking a stroll up Fifth avenue, or in other words, giving the ladies a treat. His shoes were sharp pointed, patent leather toes, with yellow tops; his pants were light, and fitted like an ell-skin; his vest was striped, his necktie red, his collar was high, and was a straight band around his neck; his coat was dark, and of the bobtailed order; his hat was enormous – it was a shiny bell with a broad curled brim. In one hand he carried a cudgel that weighed five or six pounds, and with the other he led a diminutive dog by a pink silk ribbon, and he occasionally puffed a very small cigarette.

For three years this worthless dude has painted the city vermillion. He seemed anxious to make acquaintance of jockeys, prize-fighters and gamblers – and whenever an extra mill was to take place Berry Wall invariably got the tip. He has had the satisfaction of seeing his name in the papers in connection with the set of his coats and the number of his pants, which was said to exceed 500. Absurd as this ridiculous and brainless young man made himself, he found plenty of young ninnies ready to imitate him.

The set of his pants and the style of his neckties became matters of paramount importance; what Berry Wall said and what Berry Wall did was quoted as if uttered by an oracle. In a few weeks New York will pass him in the street; few will know him – none will notice him; there will scarcely be enough left of this despicable dude to awaken a respectable contempt. And so passes out of our daily life one who in three years has spent a large fortune, which gave him an opportunity for a great and noble life, a life of usefulness, a life of honor, but he chose the fool’s part – and like a fool he perishes.

“King of the Dudes,” Broadbrim (special correspondence of The Times), The Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1885, page 2.

Some descriptions of his clothing habits prior to public awareness of his financial problems give what may be a more realistic accounting of his inventory.

He changes his dress three times a day. His wardrobe consists of 35 or 40 suits in different styles of checks and solid colors.

The Buffalo Commercial, July 13, 1885, page 2.

Some reports listed him as an ex-King at the time of his bankruptcy.

Mr. E. Berry Wall, of New York, who earned the title of King of the Dudes by the superior idiocy with which he spent his father’s money has now, it is said, been deposed. Like his royal cousin, the King of Bavaria, he has exhausted his cash and credit, and now that his money is gone he must resign his proud titles and dignities. . . . But now he has sold his horses, he is not setting up the champagne after the play, and he is overhauling his stock of trousers and silk stockings to see if he can raise the wind with the old clothes man.

Evening Star (Washington DC), September 5, 1885, page 4.

A viral joke from 1886 suggested that Wall abdicated the throne willingly a year later, after encountering someone even more fashionable than he. The anecdote foreshadowed, and may have influenced, his supposed fashion face-off with Bob Hilliard a year later.

The joke first appeared in a Boston newspaper. The scene, “a short time ago” at the Turf Club in New York City; the new “King” was identified as “Mr. James Fall, of Louisville, Kentucky.”

The “King of the Dudes” Abdicates.

The Boston Traveler prints the following story, told to its Washington correspondent: “A short time ago I went over to New York on some business, and in the evening I sauntered into the Turf Club, where I have many friends. Among the gentlemen present was Berry Wall, the ‘King of the Dudes.’ He was more exquisite than ever, and sat there chattering with some of his subjects. In a short time there was a commotion at the door. The ‘king’ never looked up, but one of his friends attracted his attention by leading up to him the most perfect specimen of a dude that I ever saw. Wall was in no way a comparison with him. The friend said, ‘Mr. Wall allow me to present Mr. James Fall, of Louisville, Ky.’ Wall was thunderstruck, but he recognized Fall’s superiority, for he exclaimed, ‘Great heavens, gentlemen! I’ve lost my crown!’ Thus did the king of the dudes announce his abdication. The new king has gone to Paris, and it is rumored that he will return with some ‘startling novelties at the opening of the fashionable season,’ as the men milliners would put it.”

Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), October 24, 1886, page 2.

A Chicago newspaper rewrote the story, replacing the specific person from Kentucky with an unnamed “young man from Chicago,” and moving the action back to a time “when Wall was in his glory in Dudedom, and bore the title of ‘King of Dudes.’” It still took place in New York City, but not at a specific location. This version was reprinted dozens of time from coast to coast, sometimes with “young man” replaced by “a rich citizen of Chicago.”

Talking about dudes, one naturally thinks of Berry Wall. I saw him this afternoon along his old stamping-ground on Fifth avenue and Broadway from the Fifth Avenue Hotel to the Gilsey. He looked the leader of the dudes as much as ever, but he has lost his grip. When Wall was in his glory in Dudedom, and bore the title of “King of Dudes,” and was very proud of it, a young man from Chicago who was doing New York met him. The Chicago young man had millions of money and few brains, and was just back from “a little across [(the pond)] ye kneow.” In get-up and manner he was a perfectly paralyzing specimen of the dude, and might have just stepped out of the pages of one of the illustrated comic papers. He was very anxious to meet Wall, as he had heard of him and his title, and believed he would strike a congenial spirit. A mutual friend brought them together. When the stranger was presented, Berry stepped back, took him in slowly from head to toes, and exclaimed, “Ye gods! I abdicate.”

Chicago Tribune, November 27, 1886, page 3.

Whether true or not, some people still portrayed Berry Wall as the “King.” He was still “King of the Dudes” the following year when he made what may be his only lasting contribution to men’s fashions when he helped popularize the tuxedo. Wall did not invent the coat, it came from England, where it had been known as the “Cowes coat.” He was not the first one to introduce it in the United States, that accomplishment is generally attributed to Mrs. Potter’s husband who was introduced to the style by the Prince of Wales. And he did not name the coat; the coat was named for a new club and country retreat called Tuxedo Park, whose influential members were early adopters of the coat.

But Evander Berry Wall may have been the highest profile fashion plate to wear the new style at the time the style was first introduced, and he was famously kicked off the dance floor by a doorman who hadn’t yet received the memo that a tailless coat was A-OK at a formal event.

Mr. E. Berry Wall, who bears the distinguishing title of “King of the Dudes,” was ordered off the floor of the ballroom of the Grand Union Hotel, Saratoga, recently, because the doorkeeper insisted that he was not in full dress. Mr. Wall wore the tailless dress-coat so popular in England for summer wear, but which was new to the attendant, who regarded it as little more than a waiter’s jacket, and insisted upon the clawhammer of tradition.

Harper’s Bazar, Volume 20, Number 38, September 17, 1887, page 643.

His name was still associated with the coat a year later, alongside one of the earliest known examples of the name of the word “Tuxedo” (as the name of the coat) in print.

Clothier and Furnisher, Volume 18, Number 3, October 1888, page 29.

Within weeks of making headlines for wearing his tailless coat at Saratoga, Wall was drawn into a widely reported battle of the Dudes with Bob Hilliard (and by some accounts at least one other contestant). The details and winner of the “battle” were disputed at the time. The existence of the battle itself may also be under dispute. It may all have been the invention of a newspaperman named Blakely Hall of The New York Sun, a friend of Hilliard’s who may have been acting as a public relations agent for him, at a time when Hilliard was transitioning from the amateur to the professional stage.

E. Berry Wall, The Morning News (Savannah, Georgia), November 27, 1887, page 3.

The first inkling of Hilliard’s claim to the title appeared in florid prose in mid-October 1887. It wasn’t reported as a head-to-head contest with Wall, but as the proclamation of a theatrical producerxiii named Major Charles E. Rice (brother of Edward E. Rice), owner of the Pickwick Theater named at the end of the piece.xiv

The New King of the Dudes.

Mr. Bob Hilliard Robbing Mr. Berry Wall of his Hard-Earned Laurels.

[New York Sun.]

One of the most beautiful tableaus of local New York life was seen yesterday in a bright October sunlight on upper Broadway. Mr. Bob Hilliard had just come out of his hotel attired in gorgeous and captivating raiment. He surveyed himself complacently in the window of the big drug store on Thirtieth street and Broadway, and then, arranging the rose in his button hole with a careless wave of the hand, he took up a position on the corner, and gazed keenly down Broadway.

Five women started back spasmodically, a car-horse sneezed, and the driver of a hansom clutched wildly at his reins and reeled half over backward.

It was at this moment that Mr. Charles Rice came out of the doors of a “Pickwick,” and catching a glimpse of the gorgeousness across the street, he gently crossed the cartracks, and, stepping up within a few feet of Mr. Hilliard, fell into an attitude of deep and admiring contemplation.

Both men stood there for a long while. Hilliard was wrapt in an introspective realization of his innate splendor, while Maj. Rice’s war-beaten countenance and clasped hands were indicative only of honest admiration. Hilliard wore varnished boots, white duck over-gaiters, gray trousers, something exceedingly fetching in the way of buff waistcoats, a scarlet tie, the towering collar, a snugly-fitting wine-colored coat, the glossiest of beavers, the reddest of gloves, and the nattiest of canes. Roses and jewelry lent the final touch to his attire.

Maj. Rice continued to stare at his friend until he had absorbed every detail of his nature and then, stepping up to him, he touched him on the shoulder and said, in a tone of deep feeling:

“Bob, you’ve won in a canter.”

“Won what?” asked the actor.

“The cup,” said Maj. Rice, shortly. “Berry Wall isn’t in it at all. He thinks he is and so do some of his friends, but he doesn’t trot in the same class. When it comes to sizing up against you in the matter of clothes he is lost in a cloud of dust before the race begins. Berry Wall! Bah! Why he isn’t in it.”

Maj. Rice conveyed the object of his admiration across the street after this, and they entered the “Pickwick” arm in arm.

Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), October 15, 1887, page 5.

Bob Hilliard, The Morning News (Savannah, Georgia), November 27, 1887, page 3.

A similar article appeared the following week, also originating in the New York Sun, but this time naming Edward Saportas (a “famous Wall Street man”xv and heir to New York’s “Cotton King”xvi) and Barton Key (personal manager for the actress, Mrs. Brown Potter, and grandson of Francis Scott Key) as the overwhelmed admirers. Berry Wall is said to have been thrown into a “state of acute and bitter woe” when denied the opportunity to buy the gloves Hilliard wore so well.

THE NEW KING OF THE DUDES.

New York Sun: Mr. Robert G. Hilliard stepped from the door of a cab yesterday afternoon, dismissed the driver with a haughty gesture and a handful of coin, and stood on the corner of Twenty-sixth street and Broadway in an attitude of deep and somber meditation. Several of the loungers in Delomonico’s moved nearer the window and gazed at the new king of the dudes. One of them, Mr. Edward Saportas, who is an old subject, and an ardent imitator of the ex-King Berry Wall, breathed hard as he gazed over Barton Key’s shoulder at the successor of the former monarch, and he whispered hoarsely:

“Where’s Berry Wall?”

“Haven’t seen him,” said Key shortly.

“Waiter,” shouted Mr. Saportas, nervously, “Go in the other room and see if Mr. Wall’s there. If he is send him in here at once.”

The waiter hurried in an came out with the information that Mr. Wall had not been there at all during the day. Then Mr. Saportas fell into a deep and earnest inspection of the man who stood on the corner engaged apparently in a futile effort to recall a date.

Mr. Hilliard was quite unconscious of the excitement he created. He had on a pair of gloves that were made to order by Jones, and which are said to have thrown Mr. Wall into a state of acute and bitter woe when he first saw them on exhibition in the window of a glove store. He made every possible effort to buy them, but he was unsuccessful to the last. They were a pale salmon tint, relieved by white stitching. Mr. Hilliard’s shirt was a groundwork of dead white with a dashing superstructure of green bars. . . .

His waistcoat looked like oil-cloth, but it was not. It was a beautiful pattern of squares and bars, one melting into the other. It was green and white, and a terra cotta shade in the binding. It was made of linen. The actor’s coat was an extraordinary bit of goods, which it is said can not be duplicated in New York. It was black, with big wooly knobs sticking out all over it, and it fitted faultlessly. . . .

He stood for a moment in deep contemplation, and then, glancing at his watch, hailed a hansom and was whirled away. This was the only glimpse that the Delmonico idlers had of the new king of the dudes yesterday afternoon.

Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 22, 1887, page 9.

A third episode of the New York Sun’s “Dude” soap-opera has Hilliard making fashion waves wearing a cape coat as early as October 24th, an “extraordinary innovation . . . not readily . . . appreciated outside of the peculiar circle of men of fashionable clothes which moves around Messrs. Hilliard and Wall.”

The New King of the Dudes.

From the New-York Sun.

. . . One question which has long been mooted in the up-town clubs may now be taken as definitely settled. Cape coats will be worn this winter, despite the disparaging remarks that have been made about them the past month. Whether it was Mr. Hilliard’s idea to nail these rumors offhand and fix the exact status of the cape coat early in the season or not is a question. When he was asked respectfully about it, he glanced carelessly at his reflection in a neighboring window and said suavely:

“The Inverness coat is to my mind rather a graceful garment. I do not know that there is a movement on foot to abolish it, but I am sure that if it is properly made it will retain its position in the affection of mankind.”

“Isn’t it rather early for a cape coat?”

“Not for me,” said Mr. Hilliard, placidly, as he carelessly untwisted a long blonde hair from his sleeve, and watched it as the northwest wind whirled it into the lap of the bronze statue of William H. Seward in Madison Square Park, “Not for me.”

Then Mr. Hilliard bowed pleasantly to the questioner and strode briskly northward. He looked wintry. His gloves were a shade thicker than those of the prevailing mode, and they were fastened around the wrist by brass clasps of a peculiarly ostentatious design. They were dogskin, and very heavily stitched. A bell-shaped beaver surmounted the actor’s smooth head, and a very high collar encircled his neck. The points of the collar were not turned forward. In this detail Mr. Hilliard takes distinct issue with Mr. Berry Wall, declaring that the collar with the turned-over corners is the fashion of last year, while the straight collar with heavy stitching is indubitably correct to-day. . . .

Buffalo Weekly Express, October 27, 1887, page 5.

The ludicrous contest caught the attention of the public, locally and nationally.

Public interest in the rivalry between Russia and England in the East and Chicago and St. Louis in the West has been for the moment transcended and eclipsed by the tumultuous, thrilling eagerness with which New York watches the competition between Mr. Robert Chesterfield Hilliard and Mr. Evander Berry Wall for the soul-satisfying title of King of the Dudes. At present the verdict seems to be that Mr. Wall has the broader and Mr. Hilliard the more highly-specialized talent in trouserings, coatings, vestings, shirtings, under-clothings, collarings, cravatings, studdings, cuff-buttonings, cuffing, hattings, gloving, handkerchiefings, and shoeings. ‘Tis a war of giants.

The Tennessean (Nashville, Tennessee), October 26, 1887, page 5.

The metropolis is more interested in the titanic struggle between Bob Hilliard and E. Berry Wall for the throne of dudedom than in the Nicoll-Fellows contest [(for District Attorney)].

Brooklyn Times Union, October 28, 1887, page 5.

The rivalry was looked on with particular interest in Brooklyn, Hilliard’s home and the city where the Walls had made their fortune. Hilliard was the hometown favorite because he liked Brooklyn. Wall, on the other hand (like Tony Manero’s dance partner, Stephanie, in Saturday Night Fever), had turned his back on Brooklyn, affecting the tastes and mannerisms of an urbane Manhattanite.

The fierce duello between two quondam Brooklynites, Mr. Robert Chesterfield Hilliard and Mr. Evander Berry Wall, in the matter of startling attire, which for a week stirred the Metropolis to its deepest depths and resulted in the vanquishment of Evander Berry Wall, was watched with breathless interest in Brooklyn. Mr. Hilliard’s triumph is perhaps a source of greater gratification than would have been Mr. Wall’s. Mr. Hilliard’s rise has been that of a self made dude, while Mr. Wall was born with a wardrobe, so to speak.

The grim old Eastern District rope twister who fathered him left ducats in plenty, though these have mostly passed away and the peddling of wine now keeps his son in trousers. Beside the young man early discarded Brooklyn as his dwelling spot and scorned the place of his nativity. He has gone about in life with chilling hauteur, unloving and unloved – only startling – while Mr. Hilliard was long a winsome young man in this town, whose stop on the Academy’s amateur stage set a parquet of the first society damsels’ hearts to fluttering, and who for years and years was the dearest of young men here. . . .

Mr. Wall is ashamed of Brooklyn. It is not recorded that Mr. Hilliard has ever been disloyal to his city. Now, from the proud throne of the kingdom of the dudes he must look upon it as a pleasant background to his career. Some Brooklyn men have attained greatness heretofore, but none ever duplicated a Fall and Winter fashion plate in a single day. Mr. Hilliard is working out his destiny.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 30, 1887, page 10.

Bob Hilliard was then a former amateur actor from Brooklyn who had only recently transitioned onto the professional stage, where he found some success and notoriety as a member of Lily Langtry’s acting company. A journalist from Brooklyn named Blakely Hall, who wrote for the New York Sun and other papers, is said to have been responsible for starting the public “battle” between Hilliard and Wall. Not only did Berry Wall credit (blame) Hall for fabricating the whole thing, one newspaper even referred to Hall as, “puffer extraordinary to his Majesty [Hilliard, King of the Dudes],” essentially a press agent (“puffery” refers to exaggerated praise, primarily for advertising purposes).

Blakely Hall had written about Wall previously. He mentioned him in an anecdote that took place at the Carleton Club. A “fiery Texan” (former Texas Congressman, Col. Thomas Porterhouse Ochiltree) supposedly droned on obliviously as the only other person in the room (Berry Wall) slept in a chair across from the Colonel. In that instance, he had some good things to say about Wall, despite labeling him the “pallid, dissipated, and worn-out child of the fastest circle in New-York life.”

A greater contrast could not be found on earth than that between the rugged, red-haired, tempestuous, and mammoth son of the Texan frontier and the pallid, dissipated, and worn-out child of the fastest circle in New-York life. Yet there was a bond that bound them together firmly – the ability to enjoy life as it passed without joining the big fight for wealth that makes New-York men the most restless and agitated of their kind.

“The Genial and Accomplished,” Blakely Hall, Buffalo Weekly Express, March 31, 1887, page 3.

Blakely Hall wrote critically of Wall’s fashion sense on another occasion.

Variegated Shirts.

Blakely Hall, writing in the Brooklyn Eagle, says: “The colored shirt mania is becoming acute, and is rapidly getting beyond control. The proudest man in town today is the one who parades Broadway with a liberally-exposed shirt-bosom formed of a background of sea green, splashed with red roses and occasional arrows of a light shade of pink, with a high white collar and a purple tie. This gentleman feels that he can defy all comers.

The only rival to this particular specimen of misdirected energy in the matter of color is Mr. Berry Wall’s waistcoat. It was built for him at vast expense, and would be the pride of Mr. Wall’s friends if it were not for the fact that the sight of it plunges them into a condition of blind, unreasoning, and violent envy. The body of the waistcoat is white, and over its surface are embroidered countless miniature representations of Mr. Berry Wall’s great race-horse Wallflower, with a jockey on his back wearing Mr. Wall’s colors, blue and white. . . .

Of all the fashions that have afflicted the town this is by long odds the most absurd.”

The Columbus Journal (Columbus, Nebraska), July 28, 1886, page 4.

Hall also wrote several articles about the power of advertising, lessons he may have applied on behalf of Hilliard in creating the dude feud.

SCHEMES OF ADVERTISING

To a very large proportion of New Yorkers notoriety means prosperity. There are more ways than one of advertising, and the way that is most sinuous and deceptive and coy is the one most in demand. Let any man start out with a new scheme for attracting public attention to his wares and his future is assured. . . .

What is known as the personal form of advertising seems to be far more in demand. A man identifies himself with something he wants to sell, and then pushes his name forward in public places as often as possible. Who has not heard of Bryan G. McSwyny, and who that has heard of him does not know that he sells shoes?

Originally he was the creature of the festive and larking imagination of Amos J. Cummings, the distinguished journalist, who saw in the solemn and grewsome humor of McSwyny a fitting subject of amusement. More for a lark than anything else he inserted the name of Bryan G. McSwyny in the newspaper for which he wrote, and which he mainly controlled, in a thousand odd and curious ways. At a distinguished reception in one of the most exclusive houses in town the name of Bryan G. McSwyny would appear between the names of the most aristocratic and exclusive Knickerbocker families. The next day the same Celtic appellation would crop up in a stock report and a dispatch from Washington. The occasional delicious interviews with Bryan G. McSwyny followed, and before long everybody in town knew the name. The shoemaker is a shrewd and clever Irishman, despite his numerous characteristics, and before long he took advantage of the free advertising that Congressman Cummings had given him. Then he began to paddle his own canoe and Mr. Cummings advertised him no more. Now nothing that is Irish in New York is a success without Bryan G. McSwyny, and as he is famous hi s shoe shop has grown prosperous too.

“Schemes of Advertising,” Blakely Hall, Brooklyn Times Union, July 9, 1887, page 3.

Blakely Hall, a newspaper writer of reputation in the East, asserts that business men in that part of the world are beginning to recognize the advantage to be derived from the employment of handsome men in offices and stores which appeal to the patronage of women.

He instances several cases. A candy store with a male beauty working in the window is thronged by women. Here is the description – which for sheer repulsiveness deserves a medal:

“. . . His hair was sleek, well oiled and beautifully banged, his color pink and white, and his narrow-chested body was encased in a beautiful blazer of pink and white silk, drawn together by a heavy and interlaced crimson cord down the front. On his head he wore a silk jockey cap, also of pink and white stripes, and his hands were rendered prominent by what might be called outside cuffs of snowy linen, which came up to the sleeve. The languid manner with which he tossed the taffy over the big silver hook was in thorough consonance with the languorous glance which he occasionally directed toward the women outside the window.”

The San Francisco Examiner, December 30, 1888, page 11.

One of the other advertising success stories Hall profiled was a “tailor’s clerk, who . . . conceived an idea . . . of advertising clothes by printing woodcuts every day in conjunction with characteristically and peculiarly written prose and poetry.”xvii That description suggests the company was Rogers & Peet, who, coincidentally, took advantage of the “Dude” craze with a series of dude-related ads.

|

| The Yankee Dood'le Do." The Sun, September 22, 1883. |

Blakely Hall was apparently a close friend of Hilliard. When rumors swirled of an upcoming duel between Hilliard and Lily Langtry’s longtime beau, Freddie Gebhard, Hall reportedly agreed to serve as one of Hilliard’s seconds.

The rumored duel stemmed from an incident in a theater in which Bob Hilliard accused Gebhard of ogling his wife from a neighboring box. Witnesses said the whole thing had been at worst a misunderstanding and more likely a complete fabrication. But the dude-king stars must have been aligned that night, as one of the witnesses sitting with Mr. Gebhard in his box was a woman popularly known as the Baroness Blanc, who (twelve years later) made headlines cavorting around with J. Waldere Kirk, during his reign as the “King of the Dudes.”

Although some reports declared Hilliard the new “King of the Dudes,” those claims may have been premature. Hilliard may have landed several fashion body-blows on Wall during his absence, but Evander Berry Wall was not down for the count. In Berry Wall’s next appearance in print, he “knocked Dude Bobby Hilliard Silly,”xviii sending him into hiding.

A DETHRONED MONARCH.

Berry Wall Finally Drives Mr. Hilliard to Cover.

New York, Oct. 23. – Mr. Berry Wall’s friends have been watching anxiously for his appearance of late, and the details of his attire are still eagerly scanned when he ventures abroad. For one or two days he was rather secluded, and it was during his absence that Mr. Robert Hilliard made a deep and profound impression on the surface of the town by usurping the place of the king of the dudes and reigning for a time with absolute success. Mr. Hilliard is still far ahead in the matter of gloves and the harmony of the minor details of his attire. But Mr. Berry Wall in the way of variety, brilliancy and celerity yesterday drover Mr. Hilliard under cover and the latter was actually discovered by one of his admirers, Mr. Chas. Plantagenet Rice, sneaking down to the stage door of the Fifth avenue theater on the shady side of Sixth avenue as Mr. Rice was emerging from the stage door of the Bijou theater. . . .

Mr. Rice glanced at Hilliard’s attire with open disapproval. The actor wore an ordinary frock suit with drab over-gaiters, yellowish gloves, a scarlet tie and a beaver hat. He had a lily in his buttonhole, but the general polish, originality and daring which had enabled him to win the title of king of the dudes, were all noticeably absent. Mr. Rice returned without a word and dodged into the stage door of the theater again. An ideal had been shattered.

In the course of three hours yesterday Mr. Berry Wall produced three distinct and palpable sensations. It was raining when he first appeared, and he wore a low crowned Derby hat, a heavy tweed suit with the trousers well rolled up at the bottom, cork soled shoes, a yellow mackintosh with a graceful shape, dogskin gloves and dark cravat and an air of gloom.

He disappeared for a while and then came round completely transformed. The sun was shining brightly, as though by arrangement with Mr. Wall’s attire. That was what is known as a cutaway suit of very light and showy material, and a huge gardenia bloomed in the buttonhole of the coat. . . .

Having partaken in his luncheon in this costume the ex-king of the dudes emerged a little later from obscurity in morning attire. He would have shamed a Parisian dandy. His frock coat was short and molded perfectly to his figure, his trousers were wide and decorated by gray bars of alternate shades, the edges of a white waistcoat appeared over the lapels of his coat, and he wore a cravat of vivid blue.

Nothing could have exceeded the absolute impressiveness of his attire. He wore the latest beaver hat, which is pointed and something like the affectations of the Alpine climber’s, his gloves were yellow, his gaiters pink, and two white roses nestled over his right lung. He carried no cane and stole languidly about with a dainty card case clasped in his hand.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 22, 1887, page 5.

To recap, at this point in the narrative Hilliard has usurped Wall’s title during Wall’s temporary absence from public view, Wall has reappeared, shaming Hilliard into hiding, but the two fashion heavyweights have not yet met face-to-face. That would change with the next installment from the New York Sun.

It was high-drama of the first order. No one was declared the victor. It was a draw – they were wearing exactly the same outfit, hilarity ensued.

THE DUDES’ MEETING.

A DRAMATIC INCIDENT THAT OCCURRED IN FIFTH AVENUE.

Berry Wall, the King of the Dudes, Meets Mr. Bob Hilliard, the Usurper, and Wall’s Attire Was Precisely Like Bob Hilliard’s.

A dramatic incident occurred on Fifth avenue the other day. It was shortly after 1 o’clock, and the sidewalks of the great thoroughfare were crowded with people. The huge throngs drifted along on both sides of the street dressed in Sunday raiment and staring interestedly from side to side. It was the most pretentious procession that New York knows.

By some curious freak of fate two young men of similar age and local fame swung into Fifth avenue at precisely the same moment and walked slowly toward each other. One turned the corner of Twenty-sixth street and started northward, and the other turned the corner of Twenty-seventh street and faced the south. Heads were turned in all directions, and the names of the two men were whispered along the street.

Each was slim of build, handsome of face and noticeably correct in the matter of attire. Mr. Berry Wall wore a dark, heavily ribbed black frock coat, gray trousers, a beaver hat with a two inch band, lavender gloves, white overgaiters, a very high and straight collar, a dark scarf and the biggest white rose that has been seen on Fifth avenue this season. He strolled along seemingly unconscious of the attention he excited, leaning heavily on his stick and staring straight in front of him with raised eyebrows and an expression of acute sorrow.

A DUPLICATE COSTUME.

Mr. Bob Hilliard’s costume was an absolute duplicate of Mr. Wall’s, even to the shade of the trousers, the white overgaiters and the massive rose. Even the material of the Hilliard frock coat was precisely similar to that of the Wall frock coat.

The crowd parted right and left as the ex-king of the dudes and the reigning monarch strolled unconsciously toward one another. Hilliard’s proportions were athletic and powerful; Wall’s were dissipated and elegant. One looked like a man of fashion, the other like a man of the world. . . .

There was a swirl in the crowd, which left an open space directly in front of the Victoria hotel. Suddenly the two idols of the town caught sight of each other. It was a thrilling moment, for it was the first meeting of the deposed and the successful monarch. It was a test which both men felt from their heels up, but which they survived with a serenity and breeding which has won them their title.

Mr. Wall’s face grew a shade whiter, but the expression did not change an iota. Hilliard flushed, but retained his expression of implacable serenity. Neither man changed his pace, and they strolled along within a foot or two of each other, and then Mr. Hilliard smiled very slightly, nodded and said casually:

“Good mawning.”

“How-do,” said Mr. Wall serenely, with just the suggestion of a smile, and a gentle beaming of the eyes. . . .

TREMENDOUSLY SHOCKED.

As the two distinguished men walked apart after their meeting, it was evident that they were perturbed. Neither of them looked back, of course, but there was a nervous acceleration of speed as they swept out of sight around the corner.

There was no question that both men had been tremendously shocked by the discovery that they were dressed in a fashion that was precisely similar. Though they knew the rumor that flew up and down Fifth avenue to the effect that they patronized the same tailor was false, yet they were nervous and ill at ease over the lack of originality they had both shown. No one knew exactly where Mr. Wall went, but it is certain that he showed up in an incredibly short time in attire that was notably and pointedly out of the ordinary run. . . .

Mr. Hilliard was seen to jump into a cab when he arrived at Broadway after his abrupt departure from Fifth avenue, and rolled hastily up town. Less than half an hour later he bounded out on Fifth avenue again and started briskly toward the park. An extraordinary metamorphosis had taken place. Shorn of his beaver hat and the dignity which a frock coat imparts, he looks like a ruddy faced boy. He was topped by a low crowned, fawn colored derby hat, which was matched to perfection by fawn colored gloves. . . .

For half an hour he strolled in Fifth avenue, and so did Berry Wall. But fate had turned against them, and they did not meet again. – New York Sun.

Champaign Daily Gazette, November 9, 1887, page 3.

If one were to believe all of the news reports, this meeting, however awkward, was not their last. The St. Paul Globe newspaper took over where The Sun left off, elevating the contest to a three-way affray, with Brockholst Cutting thrown into the mix. The Globe’s reports described a more elaborate, formal contest, with multiple outfit changes over multiple days, odds-makers and betting. The contest described in the Globe was also more democratic, with public voting and pandering appeals for support of the Scotch and Irish voting blocs. Brockholst Cutting is also said to have pioneered the one-glove look, a century before Michael Jackson.

Sadly, however, this version of their “feud” does not appear to have been reprinted much, if at all, beyond the Twin Cities. If it had been, the legend of E. Berry Wall would have become even more entertaining than the hip-boots-on-a-snowy-day myth. Luckily for Michael Jackson, however, the one-glove fashion statement remained unknown, waiting for a revival in another century.

Still another exciting element has been added to this bitter contest by the entrance into the lists of Brockholst Cutting, who is the candidate of fashionable society for the title. Mr. Hilliard is backed by the theatrical profession, who stand ready to lend him the choicest of their costumes to carry on the fight. Berry Wall is upheld by the club men about town, while Brockholst Cutting glories in the support and admiration of society youths and maidens. . . .

Mr. Wall’s principal tailor is said to have become insane in the heroic effort to respond to his customer’s demands for startling effects, and that gentleman is understood to have sent to London for a new tailor. When he arrives, the friends of Mr. Wall predict that the enemy will be routed at the first charge.

While the matinees were coming out yesterday Mr. Hilliard leaned up against the entrance to the Fifth avenue theater and received the unstinted admiration of the crowd. No rainbow ever seen in this part of the country was a patch to him. . . .

Hilliard stock boomed, and in the pools which are being sold every evening at the Hoffman house the betting was Hilliard, $60; Wall, $30; Cutting, $10.

Friends of Mr. Cutting grew jubilant as he walked out of the Knickerbocker club in the afternoon. He wore a sack coat with checks five inches wide, low-cut black silk vest, which disclosed an elaborate pique shirt and a scarlet tie, a pearl-gray derby was perched on the back of his head, allowing a good view of his brown bangs, and his trousers were wide enough to cover a flour barrel. He swung a small telegraph pole in his right hand, which was ungloved, his left hand being covered by a blue glove.

It is understood that the three contestants will make a gigantic fight this week for the throne. Mr. Hilliard thinks that he has a plan which will carry him in a winner. He will appeal to national sympathies for popular support.

On Monday he will promenade Broadway in a kilt and with bare legs. A Scotch cap and plaid cape will be a portion of his outfit, and his friends are trying to get him to carry bagpipes. The Scotch vote will then be solid for Hilliard.

On Tuesday the dude actor will aim at Irish sympathy. He will wear Knickerbocker trousers of black velvet, a pot hat and a green necktie. A shillalah will be carried in place of the usual walking-stick, and even a short clay pipe may be a portion of the attire. On each day Mr. Hilliard will appeal to a different nationality, and he believes that this will place him far ahead in the race.

Hon. Tom Ochiltree has offered to lend Berry Wall his hair and mustache for a final effort at supremacy, and Mr. Wall may accept the offer. He is having his 365 suits of clothes looked over, and hopes to arrange a combination from among them that, in the words of an admirer, “will knock the other fellows silly.”

Mr. Cutting has been consulting with his society friends about his chances, and his Knickerbocker club admirers are busily designing new and gorgeous apparel for him.

Meanwhile the tailors are urging on the contest and are hoping that a few other aspirants for the title of King of the Dudes will come forward to continue the boom in the outfitting business.

The St. Paul Globe, November 6, 1887, page 20.

Nearly every modern reference to Berry Wall as the “King of the Dudes” includes some version of an incident said to have taken place a few months later, during the blizzard of 1888. Wall is said to have bested Hilliard in a “Dude” duel by walking up Fifth Avenue snowy day wearing a pair of hip boots borrowed from Hilliard’s stage wardrobe.

That story, however, first appeared in print in 1940, shortly after Wall’s death. It has not been found in any of the contemporary accounts of their supposed rivalry during the 1880s. A further problem with the story is that it appears to be a mixed-up retelling of a story first published in 1931. The 1931 version of the story is nearly identical with the 1940 version except that it was Hilliard who supposedly beat Wall with his own hip-boots, not the other way around.

The story appeared in the book, “Peacocks on Parade” (New York, Sears Publishing Company (1931)), by Albert Stevens Crockett, the former press agent for the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. The story appeared in excerpted or paraphrased form in several newspapers at the time of publication. And, it’s not even clear whether the story was taken seriously in 1931; the headline above the story in one newspaper read, “Al Crockett Spins Yarn About Old Waldorf, With Oscar, Berry Wall and Robert Hilliard in the Leading Roles.”xix

Berry Wall was a figure show all by himself, that people always hoped to see when they came to New York. He was in a sense, the leader of the rebellion against clothes that didn’t fit, a rebellion that swept the country in the late ‘80s and banished the loose collar, the baggy pantaloons and the high boot. Berry Wall became such a model of sartorial splendor that a newspaper dubbed him “King of the Dudes” and he became the basis for feature stories that were copied everywhere. In time another newspaper tried to reap benefit from similar publicity by setting up a rival candidate for the title of champion dude.

This nominee was Bob Hilliard, actor. According to the chroniclers of the time, Hilliard caused Berry Wall the greatest annoyance of his lifetime by appearing one day in boots which were entirely outside anything Champion Wall’s wardrobe possessed. It happened during the great blizzard of March, 1888.

“Hilliard had been playing the role of a western gambler,” Crockett writes, “and, as part of his costume had had a bootmaker build for him a beautiful pair of patent leather boots that came all the way up to his hips. One the twelfth of march, New York remained practically snowed under, but on the morning of the thirteenth, when some of it had been dug out from its Arctic blanket, Hilliard, who was snowed in at the Hoffman House with a crowd of familiars, including Maurice Barrymore, Street MacKaye and Barney Deutch, the ‘man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo’ – bethought himself of the patent leather boots as a solution to his personal difficulty. So he managed to make his way home, climbed into them, strutted through the snow all the way back to the Hoffman House and became the envy of all his fellows.

“Berry Wall saw the marvelous sartorial achievement, and it was weeks before his biographer and sponsor could get him back into a good humor.”

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 13, 1931, Sunday Magazine supplement, page 4.

Nine years later, after his death, the story was retold with Wall as the winner.

During the blizzard of 1888 he walked into the Turf Club in New York for his morning cocktail, wearing heavy patent-leather boots that came up to his thighs.

“A man should be prepared for all kinds of weather,” he remarked.

Nobody knew where boots like that could be obtained or how he came to have them on hand. By this original stroke he triumphed over his rival, Bob Hilliard, known as the handsomest man on the stage. Hilliard and Wall had been equally admired as mirrors of fashion. But Hilliard was laid up by the blizzard and that put Berry in the lead.

Minneapolis Star, June 9, 1940, The American Weekly magazine section, page 9.

New York was, in fact, snowed in by a blizzard that began on March 11th and ended on the morning of the 13th. It seems plausible that Bob Hilliard might have put on a pair of hip-boots to get around in the snow. But the legend of Berry Wall embarrassing Hilliard with Hilliard’s boots is likely fake news. Even in the original story from 1931, in which Hilliard supposedly embarrassed Wall with his stage boots, there is no suggestion that the boots were worn as part of any sort of contest.

For his part, Berry Wall claimed not to have had any kind of fashion rivalry with Hilliard, as he noted in an interview in his home in the Croisic apartments, across from Delmonico’s on Twenty-Sixth Street. But he still had nothing good to say about Hilliard’s clothes.

DOESN’T MIND NEWSPAPERS.

“What did you think of the newspapers describing or pretending to describe the clothes you wore on various days last fall, and comparing them with the raiment of Bob Hilliard, the actor?”

“I didn’t think anything about them particularly. I didn’t mind them. I don’t mind anything the newspapers say. I’ve got tired of doing so. Of course, it is ridiculous describing Bob’s clothes. Yes, I know Bob. I’ve known him for years. He is an exceedingly nice fellow; but I shouldn’t think from what I can see casually in the street that he has very much of a wardrobe.”

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 29, 1888, page 9.

Two years later, Wall addressed the meaning of “Dude” (he didn’t know what it meant), his views on fashion, and the newspaper accounts of his “rivalry” with Bob Hilliard. He made the comments in a round-table discussion with nine other prominent men; writers, poets, actors, gastronomes, attorneys and journalists. A transcript of their conversation appeared in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, one in a series of round-table discussions with interesting people, hosted and reported by its editor, John Marshall Stoddart.

Round-Robin Talks, III.

. . . . One who had never seen him before and who had read newspaper accounts of his appearance and behavior would scarcely imagine this to be E. Berry Wall, sometimes spoken of and always written of as “The King of the Dudes.” He is a good-natured, open-hearted, average New York man-about-town, with far more common sense than most of his critics. He does not carry a big cane, or wear plaid clothing, or use a single-eyeglass, or punctuate his talk with “ahs.” He has the muscles of an athlete, and can hold his own in a thoughtful discussion. . . .

[After several minutes of conversation, Brook draws Wall into the conversation for the first time]

Brooke. – Wall, tell us how we should dress.

Megargee. – I believe Brooke is turning dude in his old age.

Mackaye. – Dress is a shell, and unworthy the consideration of men who wish to reach the kernel.

Fales. – Dress is a mocker; strong plaids are raging.

Wall. – Men who affect to despise dress are not honest. We all have a vanity in that direction, although it may find its expression in different forms. According to the manner of the people he has been longest associated with, Buffalo Bill is one of the best-dressed men I ever saw. And in this I have the endorsement of my friend Oscar Wilde. Yet when he walks along Broadway, all stare and some laugh at his wide-brimmed hat and the long, curling hair beneath. I would not recommend a hod-carrier to mount his ladder attired in a swallow-tailed coat; and yet if it is wrong for me and you give some degree of attention to the details of our apparel, why should we not all dress in the garb of the Quaker? To dress well may not be the chief end of man, but the character of his attire certainly has a great influence on his position, and consequently on his state in life. . . . I don’t imagine that I am better qualified than another to declare what constitutes perfection in dress, but I think that among gentlemen there will be no dissent from the proposition that the best-attired man is he who dresses with quiet elegance and whose apparel does not instantly catch the eye by some glaring detail.

I wish to say a few words upon a subject that I don’t clearly understand, and that is what is meant by the much-used word “dude.” I don’t know how it arose, and it is so variously employed that I am utterly at a loss to comprehend its meaning. So far as my observation goes, it appears to be most generally applied to young men who wear very small hats and very large and very loud clothing, and who are never without canes as thick as themselves. These youths are unquestionably the worst-dressed persons who disfigure Broadway.

Stoddart. – But Wall, if you do not know what is meant by the word dude, to whom can we go for information? There is a popular idea that you are the “King of the Dudes.”

Wall (laughing). – Yes, I believe that I was once supposed to enjoy that title; and it brought me much undeserved and undesirable publicity. If I am not mistaken, Blakely Hall, of the New York Sun, was the originator of it. I am sure that he did not mean anything unfriendly, but owing to some one-time extravagances of mine in dress and equipages and horses – foolish extravagances, if you wish – he saw an opportunity to exploit me in a series of articles which exhibited the cleverness of his pen and did not lessen the contents of his purse. In that way, so far as my recollection goes, the term King of the Dudes was created and applied to me. But you must bear in mind that I am now a “back number.” Whether it is because I am getting along in years, or because other men pay more attention now to dress than I do, or because people become tired of hearing one person talked about in connection with the same thing, or for some other reason, the title has passed away from me, and I have laid down the scepter of my inglorious kingdom without a regret.

Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, Volume 46, October, 1890, beginning at page 537.

Reports vary as to whether Berry Wall won or lost that week, but events far from their Fifth Avenue battleground may have stripped him of the title for other reasons.

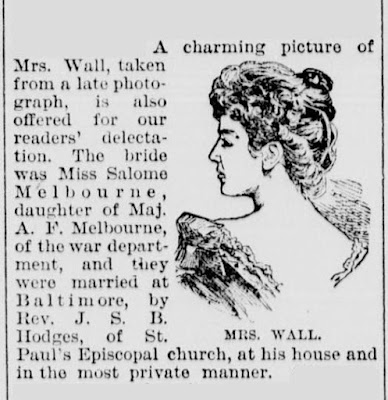

THE EX-KING OF THE DUDES.

E. Berry Wall and His Comely Bride, Nee Melbourne.

The recent marriage of E. Berry Wall, “king of the dudes,” to Miss Salome Melbourne, has sent a tingle of delicate emotion through all the aesthetic nerves of society and given the court reporter of the press a thrill as if an army of humming birds were skirmishing down his spine. The tingle is natural, and the thrill is fully justified; for this is an important affair, and dudedom has not enjoyed such a sensation since Berry’s former rival, Bob Hilliard, committed the unpardonable faux pas of wearing a cape coat on a mild October day. This blunder, the public will remember, was followed by a worse; in a desperate effort to redeem himself Mr. Hilliard appeared for an entire hour on Broadway, on the afternoon of Oct. 14, 1887, a north wind blowing, in a suit adapted to an August lounge – waistcoat of white silk, gloves pale gray, cravat of white lawn, loosely knotted, and coat of soft material, finely ribbed and slate colored. That ended his pretentions and E. Berry Wall has since reigned “king of the dudes,” without a rival.

But, of course, his marriage dethrones him.

. . . The marriage was nominally a surprise to the lady’s parents. The couple met by appointment at the St. James hotel in Baltimore, and, after some unusual difficulties in securing the license, the man with seventeen trunks and 100 suits was married in his traveling dress. Of course there is much speculation as to his future, but it is only speculation, and the public is sufficiently well informed as to his gorgeous past.

Burlington Weekly Free Press (Burlington, Vermont), December 30, 1887, page 7; Chetopa Advance (Chetopa, Kansas), February 15, 1888, page 4.

Unsurprisingly, many of the “facts” about his bouts with Hilliard are precisely opposite of those reported at the time, but the truth of the matter is less important than the entertaining nature of the prose.

But Wall did get married. News of the nuptials leaked out a week or so after the fact, but Berry Wall was reportedly in Washington DC as early as October 24, 1887, which, if nothing else, should definitively put a nail in the coffin of any likelihood in the truth of at least their final, supposed meeting in identical costume. Some reports of his time in Washington, however, maintained the conceit of his feud with Hilliard, and even hinted at the upcoming nuptials.

MR. B. WALL IN WASHINGTON

THE KING OF THE DUDES CAPTIVATING THE NATION’S CAPITAL.

Invisible for Four Days on Account of the Drizzling Rain, Except at the Ivy City Races, but Yesterday he Came Out with the Sun in All his Beauty of Raiment.

Washington, Oct. 29. – For five days Washington has been the proud possessor of Mr. Berry Wall, the erstwhile king of the dudes. His reign, however, has not been a brilliant one. This was owing to no lack of attraction in the person of Mr. Bob Hilliard’s rival. It was all due the weather. From last Monday morning until late this afternoon, more than five long days, the sun never once shone on the ungilded dome of the Capitol. . . .

Mr. Wall will remain all next week in Washington, because the races do. . . . Mr. Wall hopes to be able to show the people of Washington that he, in fact, and not Mr. Bob Hilliard, is the real king of the New York dudes. It has been whispered that Mr. Wall will appear at St. John’s Church to-morrow afternoon.

The Sun, October 30, 1887, page 14.

Before news of his marriage stripped him of his title, he still clung to the title. He even threw shade on Washington DC, provided the quote was genuine and not another fabrication.

Berry Wall Denies that He has Abdicated.

From the Washington Post.

“You don’t take offense at the newspapers when they term you the king of the dudes?” the reporter asked.

“Not at all, my dear sir,” said the distinguished gentleman from New York. “On the contrary, I should be offended if they didn’t call me so. I think really that I have fairly earned the title. What rather offends me is that I have noticed a disposition lately in some of the newspapers to put me down as the ex-king of the dudes. Now, that is not fair. Let a popular vote be taken, and you will find that I reign still without a rival.”

“In Washington, as well as in New York?”

“Oh,” said Mr. Wall, with a smile of something like pity, “you have no dudes in Washington.”

The Sun, November 10, 1887, page 4.

When news of their vows finally broke in New York City nearly a month later, they stripped him of the title.

[T]he world has made some progress, for the King of the Dudes has got married, and that amounts to abdication.

Life Magazine, Volume 10, Number 261, December 29, 1887, page 372.

Colonel Ochiltree read the news from the New York World to a small crowd of young men gathered at the Hoffmann House. Despite Wall’s stumble, they refused to restore Hilliard to the throne.

Col. Ochiltree took up a copy of The World and cast his lynx eye carelessly over its columns. . . . Suddenly Ochiltre uttered an exclamation of surprise, the newspaper dropped from his hands, his eyes rolled, his face flushed in an alarmingly apoplectic manner, and no one could have beheld him without emotion.

“Tom!” said his friend. “Speak, old man! What is it?”

The Colonel groaned. “Oh, Brock,” he began. His voice was too thick to continue. . . . “Look there,” he said loudly, pointing to The World. “Look, I say,” his hand shaking as he pointed. “I am a friend of that man and see what he’s gone and done! The boss of society, the fellow whose name is in the public prints day after day, the cynosure of all eyes, has gone and – pshaw! – married!”

“Brock” took up the paper and read the head-line: “The ‘King of the Dudes’ Married.”

. . . In the barroom, within half an hour, there were at least nine young men all full of the news of Berry Wall’s marriage. They were evidently elated. It is a well-known fact that the reign of the king of the Dudes, like that of other kings, has often been menaced by insurrection. Why should Wall monopolize public attention, by Jove, when there are dozens of men who dress as well? We like Wall, dontchernow, but his friends are making an ass of him. Such sentiments as these have long been prevalent.

Berry Wall has now retired. The resignation of Grevy from the French Presidency was certainly not half as interesting to the jeuness doree of this city as that of Mr. Wall. His future, as a married man, will be absolutely uninteresting, from a sartorial standpoint, at any rate.

Said one of these Hoffman House Daniels, “Wall won’t care a fig now whether his tie is pink or yellow – what married man does? He won’t be able to spend so much time at his tailor’s – his wife might think he was somewhere else. Oh! What a fool to marry and blight his prospects – and such prospects! We’ve heard the last of Berry.”

. . . A gentleman from Washington came into the hotel later and he was pounced upon for information, of which, of course, he had little.