The elephant has been a symbol of the Republican Party since at least 1874. Credit for establishing the connection between elephants and Republicans generally goes to a political cartoon by Thomas Nast, published in Harper’s Weekly.

In the cartoon, wild animals stampede through the woods, scared by the braying of an ass (labeled the New York Herald) cloaked in a lion’s skin (labeled “Caesar”). An Elephant representing the “Republican Vote” is about to stumble into the chasm of “southern claims chaos”; the Democratic Party, a fox, lies in wait beneath a bush at the edge of the chasm. At the time, the Democratic-leaning Herald was engaged in fear-mongering about the specter that President Grant would seek an unprecedented third term in 1876, becoming a virtual “Caesar.” The tactic was used during the off-year election of 1874 to scare Republican voters into voting for Democrats for the House and Senate, to avoid granting Grant Imperial powers.

“The Third-Term Panic, ‘An Ass, having put on the Lion’s skin, roamed about in the Forest, and amused himself by frightening all the foolish Animals he met in his wanderings.’ – Shakespear or Bacon,” Harper’s Weekly, Volume 18, Number 932, November 7, 1874.

The subject matter of an animal stampede was borrowed from a fake-news hoax published in the Herald a few days earlier, about escaped animals from the zoo rampaging, menacing and eating citizens across the city – a forerunner of Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds” radio scare more than half-a-century later.

Over the following months, Nast returned to the Republican-as-elephant metaphor time and again, helping cement the image of an elephant as representative of the Republican Party. The second example suggested that the fear-mongering had succeeded. The elephant had fallen into the trap, the wolves and vultures are closing in, and the New York Herald (in the familiar guise as an ass in a lion’s skin) and the Democratic Party (represented by a fox) look on from the upper right-hand corner.

“Caught in a Trap, the Third-Term Hoax,” Harper’s Weekly, November 21, 1874, page 960.

Nast never explained why he used the elephant to represent Republican voters, but twenty years later, a Republican Party publication credit him with establishing the symbol.

So it was accordingly done by Mr. Nast, and the elephant as the Republican vote was represented as one of the animals beginning to be frightened by the ass in the lion’s skin. . . .

The aptness of the idea, the peculiar fitness of the illustration, were at once recognized. The Republican elephant had come to stay. In the ensuing numbers of Harper’s and other papers Mr. Nast used it again and again; the elephant as the Republican vote in process of time developed into the elephant as the Republican party, and as typical of the party it has been used ever since, not only by its author, but by other and less original cartoonists. Such is the origin of the Republican elephant, the representative and emblem of the G. O. P.

“The Elephant and the G. O. P.,” Nathaniel A. Elsberg, The Republican Magazine, Volume 1, Number 1, June 1892, page 64.

Despite the official vote of confidence, however, there are several earlier examples of Republican elephants, raising the question whether Nast created the symbol or borrowed it from a pre-existing tradition.

In his 1968 book, The New Language of Politics, William Safire identified what he said were two earlier examples, one from an 1860 issue of a Republican publication called The Rail Splitter,[i] and another from Harper’s Weekly in 1872. Other researchers have previously and independently identified two Civil War-era images of elephants celebrating Union military victories and Republican electoral successes in 1864.[ii]

Of the two examples noted by Safire, the one from 1872 appears to use the elephant as a symbol of the Republican Party. The one from 1860of an elephant wearing boots, on the other hand, appears to be simply an advertisement for boots and shoes, coincidentally in a Republican publication.

As for the two images from 1864, the Early Sports ‘n’ Pop-Culture History Blog believes they are the earliest known example of a decade of sustained, occasional use of boot-wearing elephants as symbolic of Republican political success in southeastern Pennsylvania, which began a full decade before Nast’s original Republican elephant cartoon in 1874.

It is not clear whether Nast’s 1874 cartoon in Harper’s Weekly (or the early example from Harpers Weekly in 1872) were influenced by the southeastern Pennsylvania tradition of boot-wearing elephants in Republican politics or not, but circumstances suggest that it was possible, even if not direct connection has been uncovered.

Nast’s choice of an elephant to represent the Republican Party may have been an independent artistic choice, but the existence of the earlier Republican elephants raises the question of whether he was influenced by an earlier tradition of Republican elephants. Tantalizingly, the single example of a Republican elephant from 1872, noted by William Safire, also wears boots.

But it’s not really an elephant; it’s a false one, representing a false Republican.

Republican Elephant 1872

In 1872, a third-party called the “Liberal Republican Party” nominated Horace Greeley as its candidate for President. Greeley, the publisher of the Democratic-leaning New York Herald, was also popular among Democrats. To avoid splitting the vote in November among three parties, the Democrats nominated Greeley for President on the Democratic ticket as well. The Democrats even went so far as to adopt the Liberal Republican Party platform, which supported equal rights for African-Americans, which was antithetical to traditional Democratic Party principles at the time. They were trying as hard as they could to present themselves as representing policies palatable to traditional Republican voters. But not everyone fell for the ruse.

A political cartoon in Harper’s Weekly in July, a couple weeks after the Democratic Convention, shows Greeley riding atop a false, stage-prop elephant. The true Democratic nature of the beast is exposed by its costume, a Confederate Battle Flag, states’ rights, a boot labeled the Ku Klux Klan, a pant leg labeled as the New York Democratic political machine, Tammany Hall, and Democratic office-seekers crowing in from the Democratic Convention in Baltimore. Nevertheless, Greeley defiantly defies anyone to say that the elephant isn’t a real, and by implication that he isn’t a real Republican, calling anyone who would say as much a liar.

“Whoever Says This Isn’t a Real Elephant is ‘A Liar!’”Harper’s Weekly, Volume 16, Number 813, July 27, 1872, page 592.

Boot and Shoe Advertisement 1860

The other early image Safire identified is something of a red herring, as it does not directly connect the elephant with Republicans. The image appeared in multiple issues of the pro-Lincoln campaign newspaper, the Rail Splitter, through its entire run of eighteen weekly issues published in Chicago during the 1860 presidential campaign season.[iii] But the content of the image is not overtly political. It is merely an advertisement for boots and shoes sold at Willett & Co..[iv]

|

If this were the only example of an elephant selling shoes, it might be reasonable to assume its use in a Republican publication might be an intentional nod to the target Republican audience. But the image of an elephant wearing boots, carrying a banner and draped in a sash was not confined to Republican newspapers. It was a popular stock advertising image used to sell boots and shoes in stores across the country over the course of many decades.

An anecdote about a young boy frightened by an “elephant in boots” in front of an unnamed boot and shoe store in Chicago nearly a decade later describes a similar image.

A Frightened Lad.

Yesterday, while a mother and son from the country, the boy about eight years of age, were passing by a boot and shoe store on Michigan avenue, at the door of which stands an elephant in boots, as a sign, the boy discovered the “animal,” and immediately commenced to scream in affright, and no moral suasion or resort to shakes on the part of the parent could induce him to pass by the object. After several trials, he was taken across the street and thus got along. It was the lad’s first experience in “seeing the elephant.”

Detroit Free Press, November 13, 1869, page 1.

Numerous other examples appeared in print over a long period of time and across a wide geographic area. Here are a few.

|

Cedar Falls Gazette (Cedar Falls, Iowa), January 2, 1863, page 2. |

Men’s whole stock kip boots at $4.00 per pair, at Sam. S. McGibbons & Co.,

Sign of the Elephant, Market Square.

St. Joseph Gazette (St. Joseph, Missouri), September 30, 1868, page 1.

The Music Hall drop curtain has been named by some wit uptown as the Bill Poster’s dream. Three new pictures have been added since we last saw this curtain; one an elephant with rubber boots on its feet, a large-sized steer, and a Modoc Indian in full bloom.

Kingston Daily Freeman (Kingston, New York), September 12, 1873, page 3.

|

Orleans County Monitor (Barton, Vermont), March 16, 1874, page 2. |

If you want to see an elephant with boots on look over our advertisements this week. C. F. Davis made the boots.

Orleans County Monitor (Barton, Vermont), March 16, 1874, page 3.

Decades later, a boot and shoe trade journal remembered the image as tried-and-true advertising gimmick.

And I like the old printed kind [of wrapping paper] with an elephant in boots on it and the little inscription, “I Get My Footwear at Laster & Fitem’s. It just suits me.”

Boot and Shoe Recorder (March 3, 1909, page 27).

The advantage of the image for advertising purposes is that it could be tailored to clients’ needs, with two blank sections (the banner and sash) to insert unique advertising copy of their choice.

Boot and shoe stores were not the only ones who used the image. The image appeared on novelty envelopes sold during the Civil War and on topical song lyric sheets sold during the war. Although these examples related tangentially to politics, the usage was inconsistent, sometimes pro-Union (pro-Republican) or pro-Confederacy (pro-Democrat).

Of three novelty lyrics sheets Early Sports ‘n’ Pop-Culture History Blog has seen, two are pro-Confederacy and one is pro-Union.

Anti-Union: “I Carry Along! The Despot’s Song!” (the “Despot” refers to Abraham Lincoln). Dated Baltimore, March 15, 1862. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Anti-Union: “Oh dear, what have we here? George B. McClellan, The Bold Engineer.” Dated, Baltimore, October 15, 1861. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Pro-Union: “Cruelty to Our Union Prisoners While in Dixie’s Sunny Land.” Undated, Johnson, Song Publisher, 7 North Tenth St., Philadelphia. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Two novelty envelopes from the Civil War era were printed with pro-Union, and therefore pro-Republican, messages.

Pro-Union novelty envelope, “The Northern Elephant, After Secession Rats. What Patrick Henry said in ’76, “Give me Liberty, or give me Death.” What Jeff. Davis says in ’61, “Give me Hog, Hominy and Slavery.” Library Company of Philadelphia.

Pro-Union novelty Envelope, “I Always Win. Winfield Scott. Jeff being unable to come to Washington to see the Elephant, Old Abe will take the Elephant to see Jeff.” Library Company of Philadelphia.

Similar elephant imagery was also used regularly and continuously in Republican newspapers, meetings and rallies, at least in southeastern Pennsylvania, from as early as 1864. And the earliest known such usage was also accompanied by the same pig, suggesting that it could have been the same publisher.

Republican Elephants – S. E. Pennsylvania from 1864

A history of Berks County, Pennsylvania, published in 1886, described the use of Republican elephants in Reading, Pennsylvania during the election season of 1876.

The symbol of the Reading Times, in signalizing a political victory on the morning after an election, for many years, was the “elephant in boots” at the head of its columns; but the Democrats desired to show by a living cartoon that they had taken its elephant captive, and were going to carry it along in their triumphant march.”

History of Berks County in Pennsylvania, Morton L. Montgomery, Philadelphia, Everts, Peck & Richards, 1886, page 486.

Although the excerpt refers to Republican elephants specific to the Reading Times newspaper, similar Republican elephant imagery can be found in at least two newspapers in two cities (Reading and Lancaster) and in reports of the activities of two Republican “Elephant Clubs,” on in Reading’s Fourth Ward and the other in Philadelphia’s Twentieth Ward.

Father Abraham – Reading 1864

A boot-wearing elephant appeared at least twice[v] in the Republican weekly “campaign paper,” Father Abraham in Reading, Pennsylvania during the Presidential campaign season of 1864. The earliest example appeared shortly after Admiral Farragut’s victory at the Battle of Mobile.

The elephant carries a banner reading, “Clear the Track!” a recurring theme in Republican elephants in southeastern Pennsylvania. The expression was a pro-Republican, political catch-phrase at the time, sometimes used in an expanded version, “Clear the track for the Union train!”[vi] It may have been borrowed originally from the motto of the “Railroad Regiment” of Abraham Lincoln’s home state of Illinois.

With “clear the track” as its motto, the Railroad Regiment will win a substantial fame for itself and its projectors, of which the noble Prairie State will yet be proud. We sincerely wish it God-Speed.

Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1862, page 4.

An elephant wearing boots celebrates Union military victories (“Mobile Surrenders to Farragut” and “Sheridan the Peace Commissioner”[vii]) and supports a pro-Union Republican candidate over a Democratic candidate for Congress (“Ancona Stock Down and Hiester Stock Up!”[viii]). The pig in the “Sheridan Goes the Whole Hog” cartoon, immediately below the elephant, is identical to the one in the anti-Confederacy envelope discussed above.

Father Abraham (Reading, Pennsylvania), Volume 1, Number 9, 1864, page 2.

Ancona would win the election that year, despite Father Abraham lampooning him as a politician who kissed unwilling babies.

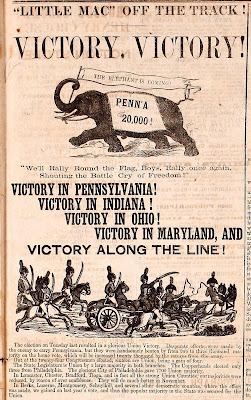

“Ancona’s Mode of Electioneering,” Father Abraham (Reading, Pennsylvania), Volume 1, Number 10, October 24, 1864, page 3.The second appearance of the elephant in Father Abraham differs slightly from the first, in that it faces the other direction and is not wearing boots. It celebrates recent victories in state elections Pennsylvania, Indiana, Ohio and Maryland (state and local elections did not always coincide with the Presidential election in November). “’Little Mac’ Off the Track” either encourages General George B. McClellan, the Democratic candidate for President to get off the track to make way for a Republican victory, or celebrates that he is off the track for election, in light of Democratic losses in recent state elections.

Father Abraham (Reading, Pennsylvania), Volume 1, Number 12, October 18, 1864, page 3.

Father Abraham was originally a “campaign paper,” with regular issues only during a campaign season.

The Father Abraham was started at Reading, as a Republican campaign paper, in July 1864, by E. H. Rauch & son, and continued during the campaign. It was revived July 1, 1866, by E. H. Rauch and published during that campaign. On the 29th of May, 1868, it was revived in Lancaster, as a campaign paper, by E. H. Rauch and Thos. B. Cochran, and continued as a permanent weekly, Nov. 20, 1868.

J. I. Mombert, An Authentic History of Lancaster County, Lancaster, J. E. Barr & Co., 1869, page 483.

There are references to it in an advertisement for “bitters” in 1866, and a reference to mutual libel suits by and against the publisher of Father Abraham and the Reading Dispatch in 1867.

Capt. E. H. Rauch, so well known throughout the State, thus speaks of Mishler’s Bitters in his campaign paper, Father Abraham.

Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), July 27, 1866, page 3.

The editors of the Reading Dispatch are in trouble, being under bail on two charges of libel – one on complaint of a lawyer named Sassaman, and the other on complaint of E. H. Rauch, editor of the campaign paper Father Abraham. The editors have also presented E. H. Rauch for libel.

Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), August 22, 1867, page 2.

Father Abraham appears to have shuttered its business by the end of 1867, but it wasn’t permanent. The owner picked up his printing press and packed off to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he resumed publication in time for the Presidential election season of 1868. Despite having the same name, he started in the new location with “Volume I, Number 1,” as though it were a different newspaper.

Despite the resetting of the identifying issue numbers, the “new” Father Abraham in Lancaster followed the same format and the same pro-Republican editorial bias as the one in Reading. It also revived the Republican elephant, this time always in boots, and added some new poses.

Father Abraham – Lancaster 1868

Father Abraham’s Republican elephant took the familiar form in its first appearance in Lancaster, celebrating early, state electoral success in Vermont.

Father Abraham (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), September 4, 1868, page 2.The new image of the elephant also wore boots, but just two. It also carried an American flag and was apparently dancing to a tune scratched out by a Racoon on a fiddle (the Racoon was the mascot of the old Whig Party, which had been displaced by the Republican Party a decade earlier), celebrating the Republican candidate, Ulysses S. Grant’s, election to the Presidency.

Father Abraham (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), November 6, 1868, page 2.

The elephant came out again the following autumn, and put his boots on in preparation for a Republican victory in local elections.

Father Abraham (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), October 8, 1869, page 4.

He celebrated with his “Happy Family” when Republicans were swept into office in citywide elections in Lancaster a week later.

Father Abraham (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), October 15, 1869, page 2.

Father Abraham brought out the Republican elephant

again to celebrate Grant’s reelection in 1872.

Times and Dispatch – Reading 1872

The Republican elephant, it seems, had found a home in Lancaster, but the people of Reading hadn’t completely abandoned the symbol. In February 1872, the Reading Times and Dispatch , celebrated Republican gains in local citywide elections by trotting out the familiar, old boot-and-shoe advertising elephant, once used to support Republican candidates by Father Abraham in Reading.

Reading Times and Dispatch (Reading, Pennsylvania), February 10, 1872, page 1.

The Republican “Tidal Wave” continued in November, when President Ulysses S. Grant won reelection, and again the Times’ Republican Elephant called for people to “Clear the Track!”

|

| Reading Times and Dispatch, November 6, 1872, page 1. |

The Reading Times’ elephant took the year off when the Republicans suffered losses in the off-year elections in 1874, but still merited a mention on November 4th, three days before Nast’s “original” Republican elephant cartoon appeared – apparently the Republican elephant had been scared away by cries of Caesarism.

Our Elephant in Winter Quarters.

The Times Elephant has been temporarily retired into winter quarters, boots, trunk and all. His fourteen years’ travel from Maine to California, year in and year out, has made him just a little tired, though we can assure our Republican friends that he is not a bit weak in the knees. He will be well cared for, so that when the great national exhibition comes off in 1876 he will “walk over the course” as majestically as ever.

Reading Times and Dispatch, November 4, 1874, page 1.

The article suggests that the “elephant” had been around for at least fourteen years, but it is unclear whether that is a reference to how long the image had been a symbol of Republicanism, or simply a reference to the beginnings of the Republican Party in 1860.

The Times’ Republican elephant made a triumphant return in 1876, following Republican victories in statewide elections in Ohio.

|

| Reading Times and Dispatch, October 12, 1876, page 1. |

The returns were did not come in as quickly or definitively in the Presidential vote a month later. In the immediate aftermath of the election, victory was uncertain. The elephant remained out of the newspaper for several days, uncertain whether it could show its face.

As crowds gathered around the Times and Dispatch newspaper offices for the latest returns, the elephant made several virtual appearances through the “magic” of a new technology, the “sciopticon,” a slideshow projection system used to project images on a large wall or screen.

Prof. Beard’s sciopticon entertainment was one of the most interesting and entertaining character. It was generally admired and the pictures were greeted with deafening cheers. They were read with ease at the extreme end of West Penn square by the aid of a night-glass. Among the number were long-faced Democrats, the Times elephant pulling the Democrats in a boat up Salt River[ix]; the Times elephant tossing a Democratic rooster; a rooster[x] sickened from eating crow and another from too much buffalo.[xi]

Reading Times, November 10, 1876, page 1.

It reappeared, cautiously, in stages, after the Presidential election, as the outcome of the election became more certain with each passing day. As initially reported, the results were still in doubt – “All Hinging Upon Florida” – some things never change.

|

Reading Times and Dispatch, November 10, 1876, page 1. |

|

| Reading Times and Dispatch, November 11, 1876, page 1. |

|

| Reading Times and Dispatch, November 14, 1876, page 1. |

|

| Reading Times and Dispatch, December 8, 1876, page 1. |

The Reading Times still used its Republican elephants in 1896, when McKinley won the election.

|

| Reading Times, November 4, 1896, page 1. |

And continued using it in the new millennium.

|

| Reading Times, February 1, 1901, page 1. |

Elephant Club - Reading

The existence of Republican “Elephant Clubs” in at least Reading and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania suggest that the elephant, as symbol of the Republican party, may have been wider than it use in local newspapers in two smaller cities might otherwise suggest.

An “Elephant Club” existed in Reading, Pennsylvania as early as 1863, although the early reports appear to be simply advertisements for social functions, not obviously related to politics.

A Rumor. – It is rumored that all the handsome young ladies (and they are all handsome) in this city, are to be at the party on Friday evening, at the Keystone Hall. The “Elephant Club” are determined to make this an affair to be remembered.

Reading Times, January 14, 1863, page 2.

|

| Reading Times, November 22, 1864, page 2. |

The name of the club may have been borrowed by a popular satirical novel published in 1856, The History and Records of the Elephant Club, compiled from Authentic Documents now in possession of the Zoological Society by ME, Knight Russ Ockside, M. D. and Me, Q, K. Philander Doesticks, P. B, This being the veritable and veracious History of the Doings and Misdoings of the Members of The Elephant Club.”

The earliest reference to a Republican “Elephant Club” in Reading appeared a month before the Presidential election in 1872. The casual reference to the “Republican elephant, boots and all,” is consistent with the longstanding, local Republican imagery in Reading.

REPUBLICAN TORCH LIGHT PROCESSION!

A Monster Demonstration

2500 MEN IN LINE

The City Ablaze with Torches

The Republican torch light procession of Saturday evening was the largest political demonstration that has taken place in this city during the present campaign. . . .

The following was the order of the procession: . . .

Fourth Ward Elephant Club, 40 equipped men.

This Club carried a handsome banner with the Republican elephant, boots and all, upon the front.

Reading Times, October 7, 1872, page 4.

Coincidentally, E. H. Rauch, the editor of Father Abraham, was active in Fourth Ward politics when he lived in Reading, suggesting a possible direct connection between the name of the Fourth Ward Elephant Club and early use of the image in Father Abraham.

Committee appointed circulate copy of resolutions that were adopted at the meeting of the citizens held in the Court House on Saturday evening September 30. . . .

4th Ward – E. H. Rauch . . . .

Reading Times, October 3, 1865, page 2.

Elephant Club - Philadelphia

The Republican Fourth Ward Elephant Club of Reading was not the only Republican “Elephant Club” in southeastern Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia, the “Twentieth Ward Elephant Club” took part in Republican rallies and meetings from as early as 1866.

The “Elephant Club,” which marched with the Twentieth Ward, were equipped in caps and capes, and had in their line the stuffed carcass of an elephant, which attracted great attention.

The Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia), October 6, 1866, page 2.

Twentieth Ward, Awake! The Union Republican citizens of the Twentieth Ward will assemble on Tuesday evening, October 2d, at 7 o’clock, at their Head-quarters, Girard Avenue and Alder Street, to join in the Torchlight Parade in the Ward, and then proceed to the Fourth Congressional Mass Meeting, to be held at Fourth and Parrish streets.

The “Boys in Blue” and the Elephant Club of the Ward are invited to take part in the parade. – By order of the Ward Executive Committee.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 2, 1866, page 7.

John W. Forney addressed the Elephant Club of the Twentieth Ward in 1871, explaining the use of the elephant as a symbol of the Republican Party.

The Elephants.

Address of Collector Forney Before the Elephant Club of the Twentieth Ward.

Last evening the Elephant Club, of the Twentieth Ward, a strong Republican organization, held their usual meeting at the hall, S. E. corner of Twelfth street and Girard avenue. . . . John W. Forney was called upon and delivered a very elaborate address upon the issues of the campaign. . . . Fellow-Citizens. “What is the Elephant Club?” is a question constantly asked by those who read your stirring calls and the proceedings of your many meetings, but little reflection will convince the most skeptical that you have chosen a happy appellation. The word “Elephant” means “a leader or chief,” and the massive animal it designates is distinguished for three great qualities, strength, courage and gratitude. Perhaps no three words more expressively typify the characteristics of the great Republican party of America.

When the Rebellion broke out it found us enervated by slavery, enfeebled by treachery and mystified in doubt. But the heart of the people soon beat responsive to the call of President Lincoln. In a few months an army was organized from the ranks of the untrained masses.

Men of the Elephant Club, your name is therefore not only illustrative of your own appreciation of your duties as citizens, but it typifies the characteristics and the mission of the Republican party to which you belong. What mean those victories by which we recover Democratic California, and redeem Democratic Wyoming and increase our force in Republican Main? What are they but so many expressions of our strength and courage?

The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 14, 1871, page 3.

Elephant Men

John W. Forney, who lectured the “Elephant Club” of Philadelphia’s Twentieth Ward on the meaning of the Republican elephant, had direct connections to local affairs in Lancaster and Philadelphia, and national political connections through his federal government experience in Washington DC. It is not proven, but it is certainly possible, that Forney could have helped spread the use of the elephant as a symbol of Republicanism from Reading and Lancaster to Philadelphia, Washington DC and beyond.

Forney ran a newspaper in Lancaster, the Intelligencer and Journal, in the 1840s, before moving to Philadelphia where he published the Pennsylvanian, a Democratic newspaper. Forney had been the publisher of the Lancaster Intelligencer and Journal in the 1840s, and later edited the Pennsylvanian in Philadelphia, before founding the Philadelphia Press and later the Washington DC Sunday Morning Chronicle (later converted to a daily).

During the 1850s, he served in Washington DC as the Clerk of the United States House of Representatives, when it was dominated by Democrats. But he switched parties at the end of the decade, and served during the 1860s as the Secretary of the Senate, when it was dominated by pro-Union Republicans. In 1871, the President Grant appointed him to serve as the Collector for the Port of Philadelphia.

|

| John W. Forney, National Tribune (Washington DC), March 22, 1900, page 5. |

John W. Forney is not the only person with political connections who could have helped created wider awareness and appreciation of the regional Republican elephant.

Jakob Knabb owned the Reading Times and Dispatch after their merger in 1868, and remained in that position until his death in 1889. He owned the paper when it first revived use of the Republican elephant in Reading in 1872. Knabb was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Chicago in 1860, where he might have seen an advertisement for Willet & Co. boots and shoes. Years later, he was a Republican Elector in the Presidential election of 1876, casting his vote for Rutherford B. Hayes. Abraham Lincoln appointed Knabb as the Postmaster in Reading, and he served in that capacity throughout Lincoln’s time in office.

|

| Jacob Knabb, Reading Times, July 19, 1928, page 6. |

In 1872, an employee of Knabb’s at the Times and Dispatch, John S. Hamaker, left Lancaster and “went to New York and worked some of the large establishments,” [xii] the same year the first Republican elephant image ran in Harper’s Weekly. Hamaker would be pure speculation, but his move to New York City is at least indicative of how plausible it is that the image could possibly have made its way to from a regional symbol to the big city, whether by his hands or otherwise.

|

| John S. Hamaker, The Times (Philadelphia), May 7, 1893, page 22. |

Edward Henry Rauch, owner and editor of the “campaign paper” Father Abraham in Reading and Lancaster, may have been the first person to use the boot-and-shoe advertising elephant as a symbol of Republican electoral success. He started his career in public service, as a court clerk and Deputy Register of Wills in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Rauch got his start in the newspaper business in Lancaster, “editing and managing two anti-slavery Whig papers – the Independent Whig and the Inland Daily,” under the tutelage of the “radical” Republican abolitionist, reformer and congressman, Thaddeus Stevens. He later struck out on his own, at various times starting, buying, publishing and editing a string of newspapers throughout southeastern Pennsylvania.[xiii]

In 1859, E. H. Rauch became the “transcribing clerk of the State Legislature and in 1860-1862, chief clerk.”[xiv] When the Civil War broke out, he joined the Union Army as a Captain, was wounded at Bull Run, and discharged in 1863.[xv] In 1864, he founded the “militant campaign sheet,”[xvi] Father Abraham, in Reading, which he revived again in Lancaster in 1868.

|

| Edward Henry Rauch, The Times (Philadelphia), May 7, 1893, page 22. |

Rauch was an expert handwriting imitator, and frequently appeared as a handwriting expert in court. He is best known today as an early progenitor of writings in “Pennsylvania German,” a sort of pidgin German mixed with English, with unconventional spelling. But his biggest contribution to pop-culture may be in helping establish the elephant as the lasting symbol of the Republican Party.

Coincidence or Connection?

It’s not certain whether there was any direct connection between the local use of Republican elephant symbolism in southeastern Pennsylvania and Thomas Nast’s use of similar imagery in 1874.

We may never know how or why Thomas Nast chose to represent Republican voters as an Elephant in 1874, and we may never know whether the Twentieth Ward Elephant Club of Philadelphia or the Fourth Ward Elephant Club of Reading played a role, but a political cartoon of a boot-wearing, Republican elephant from Philadelphia published in 1889 raises the possibility that someone may have been aware of, or assumed the existence of such a connection.

The cartoon appeared in the national humor magazine, Puck. A bill poster in Quaker garb (a dead giveaway for Pennsylvania, which was founded by William Penn, a Quaker), rides atop a GOP elephant. The elephant is covered in posted bills (advertisements), including several for Wannamaker’s, a large department store in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The image is a reference to a political scandal involving John Wannamaker, the founder of Wannamaker’s Department store, who had just been appointed Postmaster General of the United States.

|

Waverly Gazette (Waverly, Kansas), April 6, 1889, page 3. |

When the Republican President, Benjamin Harrison, appointed John Wannamaker Postmaster General of the United States, critics accused him of buying the office, in part through large advertising buys in influential newspapers. The excessive number of crass advertising bills on the elephant brings to mind the advertising buys. The elephant refers to the party accused of perpetuating the scheme. The specific use of the stock advertising image of the boot-wearing elephant could also be an allusion to the advertising scandal.

|

| "Too Much Shop," Puck [1889]. |

To be fair, there were numerous other examples of Republican elephants before 1889, most of them not wearing boots. But the question remains, however, whether the Puck’s use of the stock advertising image of a boot-wearing elephant in 1889 is a conscious nod to the early, southeastern Pennsylvania use of Republican elephant imagery or a happy coincidence.

Legacy

Whether or not the bebooted elephant of the Reading Times is related to barefoot pachyderm in Harper’s Weekly, Thomas Nast seems to have popularized the Republican elephant, which has since become the official and permanent mascot of the Republican Party. But the existence of the one prior (1872) example in Harper’s Weekly and the several earlier examples in southeastern Pennsylvania (from as early as 1864) raise the possibility that there was an known, pre-existing tradition of Republican elephants in southeastern Pennsylvania before Thomas Nast’s first use in 1874.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the stock image of an elephant wearing boots and carrying a banner is still available today, and available for purchase on stock image sites.

It is even used on occasion in connection with Republican politics.

Some things never change.

Its use today is almost certainly because it is a cheap, readily available image, with no conscious awareness of its longstanding history as the first Republican elephant. Perhaps this post will change that.

[i] Image viewable at HarpWeek.com (https://elections.harpweek.com/1864/RS04.htm), crediting Chicago Rail Splitter, June 23, 1860, page 4.

[ii] “Hurrah for the Gunboats!!!! The ELEPHANT is Coming! Clear the Track!” HarpWeek.com (https://elections.harpweek.com/1864/FA02.htm), crediting Father Abraham, September 22, 1864, page 2; “’Little Mac’ Off the Track! Victory, Victory!” HarpWeek.com (https://elections.harpweek.com/1864/cartoon-1864-Medium.asp?UniqueID=4&Year=1864 ), crediting Father Abraham, October 18, 1864, page 3.

[iii] Charles Leib published eighteen weekly issues of the pro-Lincoln campaign newspaper, the Rail Splitter, from June 23, 1860 through October 27, 1860. Six issues of the Rail Splitter are available for download and purchase at paperlessarchives.com. A low-resolution preview is available on books.google.com. The seller states that six issues are available, but it appears that there are only five, there being two identical copies of one of the issues. One of the five issues appears to be a special issue, not numbered in the series, featuring cartoon images from earlier issues. Of the four, unique numbered weekly issues for which previews are available on Google Books, every one of them features the Willet & Co. boot and shoe advertising image of an elephant wearing boots, including numbers 1 (June 23), 3 (July 7), 10 (August 25) and 18 (October 27).

[v] Eleven of sixteen issues of Father Abraham are available online at archive.org, via a “curated grouping” of documents from LincolnCollection.org. The original documents are held by the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

[vi] The Wyandot Pioneer (Upper Sandusky, Ohio), September 16, 1864, page 2.

[vii] “Peace Commissioner” was an ironic title used with reference to Union military leaders, whose military successes would eventually lead to peace. A photographic print produced at about the same time, for example, shows seven “Peace Commissioners for 1865: Sheridan, Grant, Sherman, Porter, Lincoln, Farragut, and Thomas.” Library of Congress, https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cwpb.07619/

[viii] Sydenham Elnathan Ancona was the Democratic candidate for Congress from Berks County, Pennsylvania in 1864, and William Muehlenberg Hiester was a long-time Democrat who jumped ship to accept the pro-Union Republican candidacy in the same district that year. Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), September 1, 1864, page 2 (“Berks County Nominations. The Democratic Convention met at Reading on Tuesday last and nominated Hon. E. S. Ancona for re-election to Congress.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Muhlenberg_Hiester).

[ix] “Salt River” or “Salt Creek,” was the proverbial place political losers were banished by being “sent up Salt Creek,” a precursor to the now-more common “Sh—Creek,” where one might be banished without a paddle today.

[x] A rooster crowing was a longtime symbol of Democratic political success. https://www.newrivernotes.com/topical_books_1913_rooster_democratic_party_symbol.htm

[xi] The image of a rooster “eating too much buffalo” is apparently a reference to a large Democratic political rally and buffalo roast that took place about a week before the election. The party is described in detail on page 486 of Morton L. Montgomery’s, The History of Berks County in Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Everts, Peck & Richards, 1886). The party had featured a send-up of the Times’ “elephant in boots” being taken captive, with two men in an elephant costume rented from the Forepaugh circus.

[xii] The Times (Philadelphia), May 7, 1893, page 22.

[xiii] Pennsylvania-German Dialect Writings and their Writers; a paper prepared at the request of the Pennsylvania-German Society, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Press of the New Era Printing Company, 1918, page 75.

[xiv] Pennsylvania-German Dialect Writings and their Writers, page 75.

[xv] The Times (Philadelphia), May 7, 1893, page 22.

[xvi] Pennsylvania-German Dialect Writings and their Writers, page 75.

No comments:

Post a Comment