In Quentin Tarantino’s classic film, Pulp Fiction, John Travolta, as hitman Vince Vega, explains the “funniest thing about Europe” to Samuel L. Jackson, as hitman Jules Winnfield. At McDonalds In France, according to Vega, a “Quarter Pounder with cheese” is known as a “Royale with Cheese” - they have the metric system.

A similar dual-name confusion complicates the search for the earliest references in print to the ice cream parlor classic, the “banana split.” Early references to sundaes with a split banana topped with ice cream were frequently called “banana royalle” (“royale” or “royal”), an alternative name that persisted for decades.

The “royalle”/“split” divide is nearly as old as the “banana split” itself. The earliest reports of a “banana split” in print appeared in Boston, Massachusetts in September 1905, and the earliest mention of a “banana royalle” in print about a month later, also in Boston.

Opinions are also split about where the dessert originated. Banana split historians generally credit a man named David E. Strickler, of Latrobe, Pennsylvania with inventing it in 1904. The basic facts of his story, however, conflict with the historical record. The pharmacy in which he says he invented it did not have a soda fountain or ice cream parlor until 1905, and the person he claims to have introduced his recipe to the East Coast via Philadelphia could not have done so until two years later.

It may have been invented in or near Boston. The earliest known reference to the “banana split” in print came out of Boston, and most of the other early examples come out of Massachusetts and New England, suggesting that a Boston origin may be more likely than Latrobe.

The “Banana Split,” or something like it, may be even older than the earliest known references to it by name. A dessert with split bananas with chilled whipped cream, instead of ice cream, was described in print as early as 1897. There are also several pre-1905 references to banana “sundaes,” although those references do not clearly describe splitting bananas lengthwise, as in a traditional “Banana Split.”

Early References

The earliest known examples of “banana split” in print appeared in connection with the national convention of the National Association of Retail Druggists (NARD), held at the Mechanics’ Hall, Boston, from September 18-22, 1905.i The Murray Company, a manufacturer of soda fountain syrups and extracts, supplied and operated a “Constellation” model soda fountain, provided by the Puffer Manufacturing Company.

The Murray Co. showed a complete line of soda water flavors, so complete that they had undertaken to supply the big Puffer “Constellation” fountain in the next booth with everything used or which might be called for. . . . A “banana split” was the piece de resistance of their menu.

Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 34, Number 13, September 28, 1905, page 305.

A Boston origin seems to be supported by an article in the October 1906 issue of Soda Fountain magazine, which mentioned that “the banana split first came into public notice at the Boston convention of the N.A.R.D.”

The Soda Fountain article mentions, without naming, the banana split said to have been served by the Murray Company at the Puffer display.

One of the features of the Boston convention was the hospitality which was offered by the manufacturers and supply houses, yet among all the beverages dispensed here, none was more novel with the ladies than the banana split.

Soda Fountain, October 1906.

The article also featured comments said to be directly from a man named Stinson Thomas, who was described as the “Chief dispenser at Butler’s Department Store.”ii His quoted comments do not directly make the claim that he “invented” the banana split, although they seem to suggest that he may have been the originator. His timeline of “a little more than a year” before October 1906 is consistent with the origin being at about the time of the NARD convention in September 1905. The article also does not explicitly mention Stinson Thomas’ connection to the NARD convention. Did the Murray Company hire him to work the Puffer display at the convention? Did he make a banana split before the convention, which was already being copied by others during the convention? The answer may unknowable, but I would like to see the original article in its original, full form, to make sure there isn’t some detail that has been left out of others’ mentions of it. Anyone have a copy?

The comments appear to be mostly from Thomas himself, despite mismatched or missing quotation marks complicating matters in the Ice Cream Joe version. I add quotation marks in brackets where they appear to be missing.

[‘]My trade here is always looking for something new,’ said Mr. Thomas the other day to a representative of The Soda Fountain, [‘]and the thought occurred to me that I might prepare a popular fountain beverage with the banana. I sent my boy out to buy a half dozen bananas, and when he returned I cut off the ends of a banana, split it open, put a portion of ice cream on top and a spoonful of crushed strawberries. It certainly looked swell, and I believed the public would like it. I began with a dozen bananas a day, and when a customer appeared to be in doubt as to what to order, I suggested a banana split. If the dozen bananas were not used up in a day, I instructed my dispensers to prepare banana splits and give them away. It is a little more than a year now since the banana split was introduced here, and it is easily our fountain leader. We use four or five bunches of bananas a day, and people come for miles to get it. At first we left the peel on the banana in the plate, but some time ago we began removing it altogether. We found the ladies preferred to have the peel removed. AS we serve the banana split today, we take a whole banana, remove the peel, and then split the banana lengthwise, and lay it on a plate. On top of it we put two small scoops of ice cream, generally vanilla. The[n] on top of each portion of ice cream we put a red cherry, with a few slices of peach between them. Half a teaspoon of pistachio and half a teaspoon of crushed walnuts sprinkled over the top completes the dish. As I said before, that is our great leader. In the busy hours of the day I am able to do little else beside splitting bananas for the dispensers.[’]

Soda Fountain, October 1906 (as quoted in Richard David Wissolik’s excellent and well-researched book, Ice Cream Joe, The Valley Dairy Story and America’s Love Affair with Ice Cream, Latrobe, Pennsylvania, Saint Vincent College Center for Northern Appalachian Studies, 2004, page 88.

The “Banana split” appeared in print again, a few weeks after the NARD convention, and once again in Massachusetts, but this time a bit further west.

Fitchburg Sentinel (Fitchburg, Massachusetts), October 9, 1905, page 6.

The earliest known reference to a “banana royalle” appeared in the “Household Department” section of a Boston newspaper a few weeks later. A reader shared a recipe for a dessert they had recently eaten in Boston, and had since made for themselves at home.

I made a dessert Sunday from ice cream like one I had eaten in Boston the week before. It was called “banana royalle.” Peel a banana and cut it lengthwise. Cut the half again at the center, and put the two pieces at a saucer. Over that a slice or tablespoon of ice cream, over that some chocolate sauce, then some chopped walnuts and on top two preserved cherries, and if you can digest all that I will come again. Let me hear how you stand it.

Real Yankee.

The Boston Globe, October 29, 1905, page 32.

A recipe for a “banana split” appeared a few months later, in the same pharmaceutical magazine that had reported the “banana splits” served at the NARD convention. It should be noted that under standard ice cream parlor parlance of the day, the word “cone” used here refers to a scoop or mound of ice cream, not an edible ice cream “cone,” for holding ice cream, as it would be understood today.iii It is also worth noting that this peel-on recipe is consistent with Stinson Thomas’ description of his early banana splits., for which he left the peels on the bananas on the plate.

Take a good ripe banana with peel on, cut off both ends split lengthwise in center with silver-plated knife. Spread open, letting the peel hold together on bottom; put a cone of ice cream on center, garnish with ground pistachio nuts and top with Maraschino cherry.

Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 35, Number 5, February 1, 1906, page 97.

In Hartford, Connecticut, Goodwin’s Drug Store sold something under a similar name, the “Imperial Banana College Ice.”iv The expression, “College Ice,” was the term used to describe what might be called an ice cream “sundae” today. “College Ice” was an alternate term for what we would call an ice cream “Sundae” today. Both expressions date to about the turn of the century (19th to 20th).

Pittston Gazette (Pittston, Massachusetts), May 16, 1906, page 8.

A recipe for “Banana Royale” appeared in print a few months later.

BANANA ROYALE. - Peel bananas and cut lengthwise; cut the halves again at the center and place two pieces in saucer or dessert plate; over that a slice or tablespoonful of ice cream; pour over some chocolate sauce, then some chopped English walnuts and on top two preserved cherries.

Buffalo News (Buffalo, New York), May 21, 1906, page 3.

By June of 1906, you could get a “banana ice cream split” at N. T. Folsom & Sonv or a “genuine banana split”vi at Nichols’ Pharmacy, both in Augusta, Maine. In July, you could buy a a “banana college ice” in Barre, Vermontvii or a “banana split” in Montpelier, Vermont,viii and a “Banana Royal” in Omaha, Nebraskaix or at the Gilchrist department store in Boston, Massachusetts.x

Advertisement for Gilchrist Company department store. Boston Globe, July 14, 1906, page 14.

The soda fountain at Gilchrist Company (as seen in 1904).

At least one news item published in 1906 suggests that some people at the time considered Boston to be the home of the “Banana Split.” The ladies at a meeting of a local chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in Rapid City, South Dakota dined on a variety of Boston-themed food, including “Boston baked beans, brown bread, tea, and Boston banana split.”xi They must have enjoyed their dessert, because someone served “Boston banana split” at a meeting of Rapid City’s “Bachelor Maids” two weeks later.xii

Initially, “Split” and a “Royal” appear to have been generally considered alternate names for the same thing.

Will some one tell me how to make banana split or banana royal? It is called by both names. Peggie Sides.

Boston Globe, December 23, 1907, page 8.

A decade later, Nellie Maxwell, a popular syndicated columnist, used the terms interchangeably in her Kitchen Cabinet column.

At the Palace of Sweets one finds many new tempting dishes that can be easily prepared at home. The banana split or banana royal is one of these. Split a well-ripened banana in two and place on a chilled plate, on the top of the fruit put a layer of vanilla ice cream and over this a little finely chopped or grated pineapple, a few chopped almonds and lastly a spoonful of whipped cream garnished with a cherry.

The Bystander (Des Moines, Iowa), September 1, 1916, page 3.

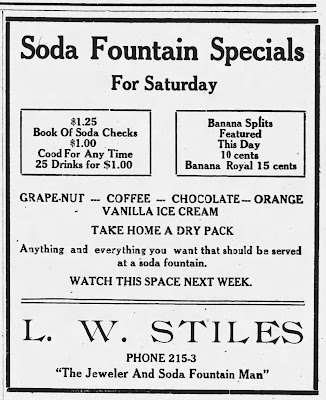

Some merchants, however, used the different terms to designate separate variants of the dessert. The “royal” was apparently fancier, priced above the “split.”

North Adams Transcript (North Adams, Massachusetts), July 3, 1907, page 6.

Springfield Reporter (Springfield, Vermont), August 20, 1915, page 1.

Both “banana split” and “banana royal” appear in a poem from a humor magazine in 1908 imagines a fast-foot future in which restaurants become passe, and people dine more regularly in convenient drug store counters.

Caricature, Wit and Humor of a Nation in Picture, Song and Story, Thirteenth Edition, New York, Leslie-Judge Company, 1911.

Decades later, some ice cream outlets seemed to have settled on cross-sliced banana rounds for a “banana royal” and lengthwise-sliced bananas for a “banana split,” although the distinction was never universal, and does not seem to have held sway in the early days of the dessert. Some ice cream historians, however, have treated “banana split” and “banana royal” as though they were always distinct desserts.

New Castle News (New Castle, Pennsylvania), June 9, 1938, page 11.

Disputed Origins

There is a split among “banana split” historians as to who invented the dessert. Latrobe, Pennsylvania generally receives the most credit, where it is attributed to a man named David Strickler. The town of Wilmington, Ohio also lays claim to the invention. A local pharmacist named E. R. “Brady” Hazard supposedly invented it there in the winter of 1907, and his cousin, Clifton, coined the name. And the October 1906 issue of Soda Fountain magazine corroborates earlier reports of the “banana split” at the NARD convention in Boston in 1905, and names Stinson Thomas, a soda dispenser at Butler & Company department store in Boston, as a possible inventor.

The Ohio claim is easily disproven by the early references to the “Banana Split” and “Banana Royale” two years before his claimed date of invention. Disproving Strickler’s story, however, is more complicated. Checking his claimed timeline against contemporary records reveals inconsistencies and impossibilities which cast doubt on his claim. The Boston story is corroborated by, and consistent with, a larger body of evidence, suggesting that the “banana split” was more likely invented in or around Boston, possibly by Stinson Thomas.

Strickler’s Story

According to most accounts, David Strickler supposedly invented the “banana split” in 1904, while working at Tassel’s pharmacy, which was then owned by Daniel Livengood; and his good friend, Howard Dovey, popularized the dish throughout the East Coast by sharing it with fellow students at a medical school in Philadelphia.1 Several details in the story are demonstrably false, in direct conflict with contemporary reporting.

Daniel Livengood did not own Tassel’s pharmacy in 1904; he purchased it in 1909. And Strickler could not have served a banana split at a soda fountain in Tassel’s pharmacy in 1904, because Mary Tassel did not install a soda fountain in her pharmacy until May of 1905. Finally, although Strickler worked there, and even served ice cream there, after the soda fountain was installed in May 1905, his friend Howard Dovey could not have introduced the treat to the East Coast via medical school classmates in Philadelphia that year, because he didn’t go to medical school until 1907.

The only “documentation” supporting Strickler’s 1904 claim is his own letter, written fifty-five years after the fact, for the purposes of getting himself selected to appear on the TV show, I’ve Got a Secret.

Strictly Facts

Mary Tassel was the first woman licensed as a “drug clerk” in Western Pennsylvania. Born in Sweden Township, Pennsylvania in about 1870, she was a graduate of the Indianapolis College of Pharmacy who had previously been licensed in Indiana. She and a partner, Harvey Amos Barkley, purchased the former McMillan Drug Store in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, in 1898.xiii The McMillan pharmacy is believed to have been the first pharmacy in Latrobe,xiv having opened for business in about 1864.xv A pharmacy in that location, 805 Ligonier Street, remained in business under successive owners, until Strickler’s Pharmacy finally closed its doors in October 2000.xvi

When Tassell and Barkley purchased the business in 1898, she had already been managing the store for “several years.”xvii Barkley, who was new to town,xviii must have been an apprentice when they bought the business, as he did not receive his license until May of 1899.xix Mary Tassell bought out Barkley’s interest in the store in 1903,xx when he quit the pharmacy to practice medicine, having been attending medical school even while helping run the pharmacy.xxi

There is no indication that Mary Tassell’s pharmacy, or McMillan’s before her, had ever had a soda fountain before May of 1905. Numerous advertisements for “Barkley & Tassell’s” pharmacy, and later Tassell’s Pharmacy, appear in the pages of Latrobe newspapers between 1898 and 1904, but none of the ones found in a search of a digitized archive advertise a soda fountain or ice cream.

Advertisements for other pharmacies in Latrobe, on the other hand, had been advertising their soda fountains and ice cream for years. Kuhn’s pharmacy had a soda fountain in the 1870s. Richey’s pharmacy had one as early as 1890. Showalter’s pharmacy had one from at least 1903. Richey’s and Showalter’s pharmacies both advertised their soda fountains in 1904.

Beginning in the summer of 1905, however, numerous articles about, and advertisements for, Tassell’s pharmacy prominently mention her new soda fountain. Mary Tassell continued advertising the availability of ice cream, sundaes and sodas every year until she sold the business in 1909, as did the new owners after she left.

In May 1905, Mary Tassell’s pharmacy installed a new soda fountain.

A New Soda Fountain.

Miss Mary Tassell is installing a handsome soda water fountain in her drug store. The fountain arrived this morning and is now being installed. It is one of the handsomest ever seen in Latrobe, and is destined to become a popular meeting place for Latrobe’s lovers of soda.

Latrobe Bulletin, May 17, 1905, page 1.

No fountain this side of the city can compare with it in quality, beauty and completeness. it is the result of years of study by the greatest soda fountain manufacturers in the country, the American Soda Fountain Company and it is aptly named the Inovation, being an inovation in the dispensing of soda, neater quicker, and more logical. The dispensers face their customers and draw from what seems to be the counter which is thoroughly refrigerated and is built of inlaid onyx, and marble.

Latrobe Bulletin, May 20, 1905, page 1.

There are no pictures of her new soda fountain, but images of the “Innovation” model, as installed in Minneapolis and Boston, give a sense of what it may have looked like.

The INNOVATION is the new apparatus of the American Soda Fountain Company, and is really the only thoroughly practical soda fountain ever constructed.

Minneapolis Journal, June 30, 1905, page 18.

The American Soda Fountain Company, when the matter of installing a new fountain was first considered, assured me that a really handsome apparatus of the “Innovation” model would prove far more profitable, in proportion to its first cost, than any less expensive apparatus of older style construction. And the results have proved that they were right, for my new fountain was a trade winner from the word go.

The American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record, March 26, 1906, page 170.

To dispense the drinks and serve the ice cream, Mary Tassell hired an “expert dispenser . . . besides the other two clerks.”xxii One of those clerks was David Strickler.

Mr. George Eitemmiller, an expert soda water mixer, and his assistant student David Strickler, do the dispensing of sodas at Tassel Pharmacy.

Latrobe Bulletin, May 27, 1905, page 1.

Latrobe Bulletin, June 7, 1905, page 8.

David E. Strickler was born in Latrobe in July 1881. At least one source suggests he started working at the pharmacy when he was sixteen years old, which would place him in the store in late-1897 or early-1898, when it was still run by McMillan.xxiii In 1963, Strickler suggested he had once held other jobs in town. As a boy, he ran the merry-ground at Idlewild Park, and later worked in a local grocery store. He said a druggist invited him to learn the business because he showed promise.xxiv When he purchased the pharmacy in 1914, it was said to be the “culmination of an ambition which he has had ever since, as a mere boy, he began to clerk there.”xxv

But regardless of precisely when he started working there, he was clearly working there in 1905, and serving drinks and ice cream at Tassell’s new soda fountain about four months before banana splits are known to have been served at the NARD convention in Boston. Is it theoretically possible that David Strickler invented the banana split in Latrobe during the summer of 1905, and it somehow made its way to the NARD convention in Boston in September? Yes. But does that theory gibe with his own story of when he invented it and how it became popular? No.

It is not outside the realm of possibility that David Strickler could have invented the banana split in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, sometime between May 23rd (when Tassell’s new fountain opened for business) and September 18th (when the NARD national meeting opened in Boston), so perhaps his mistaken recollection was only one year off. But that would leave at the most, somewhat less than four months during which the apprentice soda jerk’s backwater invention could trickle out of Latrobe and into to Boston, where it gained widespread exposure and immediate notoriety. It sounds like a stretch, but there is at least one possible route.

Mary Tassell was active in the National Association of Retail Druggists. She served as secretary of the Westmoreland County chapter of retail druggists in at least 1905 and 1906.xxvi She even represented Pennsylvania at the national convention in Atlanta, Georgia in 1906.xxvii But there is no evidence that she attended the national convention in Boston in 1905, where banana splits are known to have been served. And even if she had attend, bringing the banana split with her, it would discredit Strickler’s own story about how the banana split became known outside of Latrobe.

On the occasion of the supposed 60th anniversary of the “Banana Split” in 1964, when Strickler was still alive and active in Latrobe, a local newspaper told the story.

At the time Howard Dovey was a attending medical school in Philadelphia and took the recipe back to Philly with him . . . Other students took the idea to Atlantic City where it really caught on and soon spread to all parts of the world.

Latrobe Bulletin, July 25, 1964, page 4.

Howard Dovey could not have shared the recipe with his medical school classmates in Philadelphia before the NARD convention in Boston in 1905, however, because Dovey did not go to school medical school until 1907. In August of 1906, Dovey left Latrobe to work at the Latrobe-Connellsville Company, where his brother was superintendent.xxviii Apparently having had his fill of the coal mines, he returned to Latrobe a few months later to reenter the local high school.xxix He left Latrobe for Philadelphia in September 1907 to attend the Medico-Chirurgical College of Philadelphia,xxx “with the idea of fitting himself for the practice of medicine.”xxxi

Strickler also attended school. He received the degree Doctor of Pharmacy from the University of Pittsburgh College of Pharmacy in May 1908.xxxii He passed the state exam in August 1908, to become a “full fledged registered pharmacist.”

Mary Tassell left the practice of pharmacy in 1909, reportedly to focus her energies on “spreading the doctrines of Christian Science.”xxxiii She sold the business to Daniel Livengood in May of that year. Livengood retained the services of David Strickler and one other employee.xxxiv Mary Tassell married Dr. H. C. Harriman in 1915, living with him mostly in Denver, Colorado. She died in a head-on automobile collision in the Cajon Pass, north of Los Angeles, in 1940.xxxv

Livengood sold a partial interest in the store to David Strickler in June 1910.xxxvi

And Strickler bought out Livengood’s remaining interest in the store in March 1914, to become the sole proprietor.xxxvii

The shop kept the name Strickler’s Pharmacy until it closed its doors in 2000.

The earliest mentions of “banana splits” found in a search of a digitized database of a Latrobe newspaper appears in 1911, in advertisements for Showalter’s Pharmacy, not Livengoods or Strickler’s.

Latrobe Bulletin, April 6, 1911,page 1.

This does not necessarily disprove Strickler’s claim, but it is curious that if he invented it, and it had since become widely known and popular, and he had since become part-owner of a pharmacy with a soda fountain for which he placed advertisements, that he would not (so far as can be determined) advertise the fact, or even advertise banana splits in his store at all, until decades later.

The earliest indication of David Strickler’s claim to have originated the “Banana Split” appeared in an advertisement for his drugstore in 1933.

P. S. - This store originated the “Banana Split,” now sold everywhere!

Latrobe Bulletin, May 26, 1933, page 12.

Boston - Stinson Thomas

The earliest known reference in print to a “banana split” appeared in September 1905, a week or so following the national convention of the National Association of Retail Druggists.

The Murray Co. showed a complete line of soda water flavors, so complete that they had undertaken to supply the big Puffer “Constellation” fountain in the next booth with everything used or which might be called for. . . . A “banana split” was the piece de resistance of their menu.

Pharmaceutical Era, September 28, 1905, page 305.

About one year later, and consistent with the earliest known reference, an article in the October 1906 issue of Soda Fountain magazine noted that “the banana split first came into public notice at the Boston convention of the N. A. R. D.” A passage from the article appears to quote a man named Stinson Thompson, described as the “chief dispenser at Butler’s Department Store” of Boston, in which he apparently describes how he made the first banana split in Boston “a little more than a year” earlier.

Full disclosure, the full text of the rare magazine was not viewed in researching and writing this piece. The brief excerpts, and one extended passage, are taken from Richard David Wissolik’s excellent and well-researched book, Ice Cream Joe, The Valley Dairy Story and America’s Love Affair with Ice Cream (Saint Vincent College Center for Northern Appalachian Studies, 2004). The book includes the most well-researched and balanced analysis of the various theories on the origin of the banana split that I found while researching this piece.

Wissolik noted that he had initially been prepared, on the strength of the 1906 article in Soda Fountain magazine, to conclude that the banana split had been invented in Boston. He had received a hard copy of the article from a man named Paul Dickson, the author of The Great American Ice Cream Book. Wissolik changed his mind, however, after receiving some newspaper clippings laying out Strickler’s claim to inventorship. Those clippings, however, were of articles published during the 1980s, not during the period of origin.

Wissolik’s book also includes the full text of a letter from Strickler, dated September 1959, in which Strickler sought to be selected to appear on the television show, I’ve Got a Secret. I’ve Got a Secret had a format similar to What’s My Line. A panel of celebrities, through questioning, tried to guess the “secret” of that week’s guest. Strickler’s secret, he claimed, was that he “made the first banana split” in 1904. Strickler was not selected to appear on the show, but the letter stands now as the single piece of supposed “documentary” evidence that he invented the banana split in 1904.

Prehistory of the Banana Split

Regardless of who invented the “banana split,” by that or any other name, it did not spring from nothing. It was not even the first known dessert to feature split bananas with a chilled, cream-based confection on top. In 1897, for example, the Buffalo Enquirer featured a recipe for “Bananas a la Creme” - bananas, split lengthwise, topped with chilled whipped cream, instead of ice cream. It was “entirely new.”

Light Summer Desserts.

Bananas a la Creme - This is an entirely new dessert - most refreshing and delicious. Take six plump, thoroughly ripe bananas, lay them in a refrigerator until they are ice cold. Just a few minutes before dinner peel the bananas, split each one in halves lengthways, lay them in a deep, oblong glass dish. Squeeze over the bananas the juice of two large oranges. Stand the dish in the refrigerator while you prepare the cream. Put a pint of rich cream in a bowl. Add to it two heaping tablespoonfuls of powdered sugar and half a saltspoonful of fine salt. Crush a dozen large, ripe strawberries and strain their juice into the cream. Whip the cream till it is stiff, and pour it over the bananas. Keep the dish in the refrigerator till ready to serve. Then ornament the top of the cream, which will be a delicate shade of pink, with a few slices of banana, alternated with strawberries cut in two.

Buffalo Enquirer, July 12, 1897, page 3.

It is not a great leap from “Bananas a la Creme,” with chilled whipped cream, to a “Banana Split” with frozen ice cream. Perhaps the big mystery is why it didn’t happen sooner.

A recipe out of Indiana suggests that someone may have split a banana open lengthwise and filled it with ice cream as early as 1903, although the recipe is not completely unambiguous on the question of the direction of the slicing.

Banana sundae - Take a small banana cut it open on the top and spread about half open. Then fill with ice cream or sherbert, preserved fruits and lastly whipped cream.

The South Bend Tribune, April 7, 1903, page 10.

A “Banana Sundae” was offered for sale in Bemidji, Minnesota, but without any specifics on how the banana was sliced or how the dish was constructed.

Bemidji Daily Pioneer, November 21, 1904, page 3.

In 1904, they sold a “Banana College Ice” in Portland, Maine, although it is unclear how the bananas were sliced. It was also described as, “not the ordinary kind,” suggesting that there had already been other college ices with bananas in them, which differed in some respect from the particular version advertised here.

Evening Express (Portland, Maine), May 10, 1904, page 2.

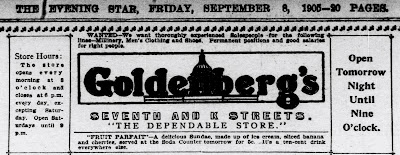

In early-September 1905, Goldenberg’s, in Washington DC, advertised a “’Fruit Parfait’ - A delicious Sundae, made up of ice cream, sliced banana and cherries, served at the Soda Counter” for 5c. No word on how the bananas were to be sliced.

Evening Star (Washington DC), September 8, 1905, page 6.

And on September 19, 1905, at the same time the NARD convention in Boston was serving a “banana split,” Burrill’s, in Ferndale, California, advertised their own “Banana Sundae” for sale.xxxviii

Admittedly, none of these early examples conclusively proves the existence of a “banana split” before the NARD convention in Boston, but they do suggest that ice cream and bananas was already a logical extension of “college ices” and “sundaes” that had already achieved a certain amount of popularity. Some of these early examples also demonstrate the use of split bananas with cream, and suggest the possibility that split bananas were used with ice cream, before the “banana split” and “banana royal” grew in popularity after the NARD convention.

Conclusions?

It seems safe to say that David Strickler’s story of “inventing” the banana split in 1904 is not true, or at least not entirely true. Although it is theoretically possible that he could have invented it after May 1905, and shared it somehow with with the 1905 national convention of the National Association of Retail Druggists in September 1905, reports of which include the earliest known references to the “banana split” in print. His boss, Mary Tassell, was active in the association, and attended the national convention the following year, so it is possible that she could have gone in 1905, although there is no evidence that she did. But that is not Strickler’s story. Strickler’s story falls apart in the face of new evidence.

The author of Ice Cream Joe was willing to believe, on the best evidence available at the time, that David Strickler should receive credit for making the first banana split in 1904. But even he was willing to entertain other theories. His conclusion was only good, he said, “[u]ntil someone comes up with new evidence.”xxxix The evidence presented here is just such new evidence.

Mary Tassell’s pharmacy did not get a soda fountain until May 1905. Howard Dove, whom Strickler credited with popularizing the banana split along the East Coast via his medical school classmates in Philadelphia, did not attend medical school in Philadelphia until years after the banana split is known to have been served at the NARD convention in Boston. Most of the early references to “banana split” and “banana royal” appeared in and around Boston and New England.

The women of the WCTU in Rapid City, South Dakota believed, in 1906, that the banana split came from Boston. And Stinson Thomas’ recollection of making banana splits with the peels on is consistent with an early recipe for banana splits, published in the same magazine in which the earliest known reference to “banana split” in print had been published a few months earlier. All these facts and more qualify as new evidence that should at least call Strickler’s claim into question.

And the “banana split” may not have been as novel as it was perceived at the time. A recipe for a lengthwise-sliced banana and chilled whipped cream dessert was known as early as 1897. It is no great leap from there to a lengthwise-sliced banana and ice cream dessert, although there is no clear reference to such a dessert until after the NARD convention in 1905. Several earlier references, however, reveal the existence of banana-and-ice cream desserts, but without unambiguously revealing whether the bananas were sliced lengthwise or not.

It is possible that someone, or several someones, in Boston or elsewhere, had made something like a banana split before it was introduced to a large, influential clientele of pharmacists at the NARD convention in Boston, in September of 1905. But it seems likely that its appearance there may have caught the attention of numerous soda fountain owners and operators from across the country, who brought the idea back to their home stores.

But perhaps it had always been a dessert looking for a catchy name. Regardless of when the dessert was first invented, the name, “Banana Split,” does not appear in print until 1905. If not for the name, it might otherwise have seemed like a simple, alternative fruit variant of a “College Ice” or a “Sundae,” which were two names for essentially the same style of ice cream dessert. A cool name like “Banana Split” or “Banana Royalle” may have been just what it needed to differentiate it from the pack, to become the beloved dessert it has since become.

The bigger question may be why the name, “Banana Split,” won out over its rival, “Banana Royalle” - and why “Quarter Pounder with Cheese” was chosen over “Royalle with Cheese,” which is objectively much cooler. What would Vince Vega do?

i The Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 34, Number 13, September 28, 1905, page 293.

ii The issue of Soda Fountain magazine was not available in preparing this article. The relevant excerpts quoted here appear in Richard David Wissolik’s excellent and well-researched book, Ice Cream Joe, The Valley Dairy Story and America’s Love Affair with Ice Cream (Saint Vincent College Center for Northern Appalachian Studies, 2004), which was available through inter-library loan. The authors of Ice Cream Joe received a copy of the Soda Fountain article from a man named Paul Dickson, who was the author of The Great American Ice Cream Book.

Dickson is not the only person to have had access to the Soda Fountain article. Columnist Ellen Rubin Wood, for example, mentioned Stinson and Soda Fountain in a 1982 article based, apparently, on information she received from the Smithsonian Institution. Lancaster Eagle-Gazette, July 7, 1982, page 4.

A reporter named Mary Kay Roth quoted from the article in a piece published in 1994. The Lincoln Star (Lincoln, Nebraska), July 20, 1994, page 11. In October of 1994, a syndicated article for Knight-Ridder Newspapers, in honor of the supposed 100th anniversary of the banana split, mentions Stinson Thomas, asserting that he was one of several soda jerks who had “made the claim that they were the devisers of the dish.”

“Butler’s Department Store,” of which no mention could be found, by that name, in a search of Boston newspapers, may refer to William S. Butler Company, a Boston dry goods store which was in business from at least the 1880s through the early-1910s,

iii For examples of cone-shaped ice cream scoopers, see my earlier post, Groundhog Day and Ice Cream Scoops - a History of Ice Cream Scoops from A-Z (Allegheny to Zeroll)). https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2023/02/groundhog-day-and-ice-cream-scoops.html

iv Hartford Courant, March 24, 1906, page 22.

v Kennebec Journal (Augusta, Maine), June 2, 1906, page 11 (“N. T. Folsom & Son made a ‘ten strike’ last Saturday, with that new ‘banana ice cream split,’ it being a late creation of some city artist, where it sells for 15c a dish.”).

vi Kennebec Journal (Augusta, Maine), June 13, 1906, page 2 (“The genuine ‘banana split,’ do try it, at the Nichols’ Pharmacy. Too delicious to be described, is this latest and one of the most tempting ice cream novelties.”).

vii The Barre Daily Times (Barre, Vermont), July 31, 1906, page 8 (“Sliced banana college ice at Drown’s. Ask the man.”).

viii Daily Journal (Montpelier, Vermont), August 22, 1906, page 4 (“When warm and thirsty just try banana split at Leland’s.”).

ix Omaha Daily Bee, July 8, 1906, page 11.

x The Boston Globe, July 14, 1906, page 14.

xi Black Hills Weekly Journal, November 23, 1906, page 4.

xii Rapid City Journal, December 5, 1906, page 1.

1 Michael Turback, The Banana Split Book, Philadelphia, Camino Books, Inc., 2004; “On the Downtown Beat,” Jack George, Latrobe Bulletin, July 25, 1964, page 4.

xiii Potter Enterprise (Coudersport, Pennsylvania), December 9, 1898, page 1.

xiv “History of Drug Stores in Greater Latrobe,” Latrobe Bulletin, January 24, 1974, page 2.

xv Merck’s Report , Volume 13, Number 1, January 1904, page 30 (“The fortieth anniversary of the establishment of the drug-store now known as the Tassell Pharmacy, in Latrobe, Pa., was recently celebrated. Matthew C. McMillan was the founder and his son continued the business until 1897, when Miss Mary Tassell purchased it.”).

xvi Public Opinion (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania), October 21, 2000, page 12.

xvii Potter Enterprise (Coudersport, Pennsylvania), December 9, 1898, page 1.

xviii At the time of his death of tuberculosis in 1907, he had reportedly first arrived in Latrobe “

xix “Successful Candidates. Registered Pharmacists That Passed the Recent Examination,” Harrisburg Daily Independent (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), May 14, 1899, page 1.

xx “Dissolution Notice,” Latrobe Bulletin, March 11, 1903, page 5.

xxi Pittsburgh Press, March 9, 1902, page 19 (Dr. Harvey A. Barkley, a student in the Allegheny Medical College, was a Latrobe visitor last week.”).

xxii Latrobe Bulletin, May 20, 1905, page 1.

xxiii Michael Turback, Banana Split Book, Philadelphia, Camino Books, Inc., 2004, page 16.

xxiv Latrobe Bulletin, September 21, 1963, page 3.

xxv Latrobe Bulletin, March 24, 1914, page 1.

xxvi Latrobe Bulletin, September 12, 1905, page 1 (“A meeting of the Retail Druggists Association, of Westmoreland county, is being held this afternoon at Oakford Park, near Greensburg. Miss Mary Tassell, of this place, is the secretary of the association and is attending the meeting.”); N. A. R. D. Notes, Volume 4, Number 32, May 17, 1906, page 17 (a report of donations to benefit victims of the San Francisco earthquake, names “Westmoreland Co., Mary E. Tassell, Sec’y, Latrobe, Pa.” as having donated $6.00 on behalf of her chapter).

xxvii Latrobe Bulletin, September 28,k 1906, page 5 (“Miss Mary Tassell left last night for Atlanta Georgia, where she will attend the convention of druggists which is in session there. Miss Tassell represents the Pennsylvania State Pharmaceutical Association.”).

xxviii Latrobe Bulletin, August 4, 1906, page 5.

xxix Latrobe Bulletin, November 12, 1906, page 5.

xxx “Medico-Chirurgical College of Philadelphia,” lostcolleges.com. https://www.lostcolleges.com/medico-chiurgical

xxxi Latrobe Bulletin, September 18, 1907, page 5.

xxxii Latrobe Bulletin, May 14, 1908, page 1.

xxxiii The Western Druggist, Volume 31, Number 10, October 1909, page 659.

xxxiv Latrobe Bulletin, May 27, 1909, page 4.

xxxv Potter Enterprise (Coudersport, Pennsylvania), March 14, 1940, page 8.

xxxvi Latrobe Bulletin, June 9, 1910, page 1.

xxxvii Latrobe Bulletin, March 24, 1914, page 1.

xxxviii Ferndale Enterprise, September 19, 1905, page 7.

xxxix Ice Cream Joe, page 90.

No comments:

Post a Comment