On Groundhog Day 1897, Alfred Lewis Cralle received a patent for a mechanical ice cream scoop. Fittingly, he was from western Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh), not far from Punxatawney, the home of Groundhog Day and Punxatawney Phil. And every year, like Groundhog Day (in the modern Bill Murray sense of the word), posts, links and comments pop up on social media celebrating Cralle as the man who “invented THE ice cream scoop.” That characterization, however, is not accurate.

Alfred Cralle invented “an” ice cream scoop, but not “THE” ice cream scoop. His was not the first and would not be last. Ice cream “scoops or measures” were available, for example, in Boston in 1890.

Boston Globe, May 25, 1890, page 8.

A widely reprinted newspaper filler-item mentioned a “new ice cream scoop” in 1892.

An inexpensive utensil is the new ice cream scoop. It costs but 40 c, and is worth several times the price to the woman deputized to ladle out the ice cream at a fair or fete. These scoops cut the cream out in perfect forms, giving Tom the same amount as Dick or Harry.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 4, 1892, page 6.

A new ice cream scoop has been invented which takes out from the freezer exactly the same amount of frozen sweetness to every customer and in exactly the same shape. After this it won’t do the young man a particle of good even if he is particularly well acquainted with the young lady behind the ice cream table at the church fair.

The Boston Globe, August 8, 1892, page 4.

Cralle’s scoop bears some resemblance to some modern ice cream scoops. But there are earlier patents that look more like some ice cream scoops still in use today than does Cralle’s. He had reportedly “received many letters from firms at Chicago, Philadelphia, Cincinnati and other cities offering large inducements to him should he wish to sell the patent outright or on a royalty,”i but it is not clear whether anyone ever manufactured any scoops according to his design.

Cralle’s scoop was not the only one inventing new scoops at the time; nor was he the first person from Allegheny County, Pennsylvania inventing scoops at the time. Defying all odds, during a three-year period from 1896 through 1898, more than a dozen patents were awarded for more than a dozen distinct designs, all to different inventors, with ever single one of those inventors from western Pennsylvania, nearly all of them from Allegheny County. A search of a worldwide patent database found no other ice cream scoop patents from anyone anywhere else in the United States during the same period.

What was going on?

The answer is suggested by a comment in a brief biography of Cralle, published shortly after his patent issued.

The invention patented by Mr. Cralle was advertised for by H. C. Evert, a well-known patent attorney in this city, last April, and immediately Mr. Cralle set his ingenious mind to work.

The Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1897, page 10.

Henry Charles Evert was “at one time was one of the best known patent attorneys in the United States,” with offices in Washington DC and Pittsburgh. In Pittsburgh, he was locally famous for a colorful home life. In 1900, for example, he maintained separate homes, one with his mother and actual wife, and a second home with his girlfriend Mollie Campbell, under the false names of Mr. and Mrs. Whitney.ii

At the time of his death at the age of 46, in February 1915, he lived with a woman named Mrs. Julia Zanestein, the mother of his two youngest children. His wife, the mother of his two oldest children, had sued Mrs. Zanestein for alienation of affection, and had her arrested and briefly jailed for failure to make payments. The legal entanglements surrounding his estate and will made for several big headlines in Pittsburgh newspapers.

Evert placed advertisements in local newspapers soliciting clients. But instead of passively seeking out inventors with inventions, he actively gave invention prompts, with lists of ideas for items readers might invent. Many of his ads, beginning as early as February 1896, included a suggestion for inventing an “Ice Cream Disher that can be easily and rapidly operated with the hand.” Later versions of the ad specified an “ice cream disher that can be operated with one hand.”

Pittsburgh Press, February 23, 1896, page 15.

Pittsburgh Press, March 15, 1896, page 23.

More than a dozen local inventors took Evert up on his ice cream scoop suggestion.iii He wrote and filed nearly all of

the ice cream scoop patents from 1896 through 1898.

Alfred L. Cralle was one of his clients. Cralle’s invention was noted in a local paper shortly after his patent issued.

For a long time the colored man has been coming to the front in the political, educational, business and industrial world, and on not a few occasions has the scientific world been benefited b the brain of the colored man. Hundreds of patents have been obtained from ideas introduced by the ingenuity and originality of the negro, and many thousands of dollars have found their way into the coffers of those who were fortunate enough to grasp an idea thus advanced before a patent was secured.

But all colored people have not been so fortunate, and Alfred Lewis Cralle, of No. 9 Olive street, this city, is one of the few exceptions. Mr. Cralle is the inventor and patentee of an ice cream mold or disher, and its practicability as a household article makes it all the more valuable.

The Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1897, page 10.

Alfred L. Cralle was born in Lunenburg County, Virginia, on September 4, 1866. He attended public schools there, and later enrolled at Wayland Seminary, Washington DC, one of the forerunners of the HBCU, Virginia Union University. Early in life, he worked with his father, a carpenter, where he reportedly developed his mechanical aptitude.iv

After leaving Wayland, Cralle moved to Pittsburgh, where he worked at various times as a porter for the Markell Bros’ drug store in the East End, and as a porter at the St. Charles Hotel. He would likely have had the opportunity to observe ice cream service close-up at either one of those positions; hotels of that era generally had restaurant service, and the Markell Bros. drug store is known to have had a soda fountainv (ice cream was generally served at “soda fountains” of the time).

It is not clear where Cralle was employed at the moment he conceived his idea, but when Evert filed Cralle’s application in June 1896, he was just starting a new job, as the Assistant Manager of the newly-formed Afro-American Financial, Accumulating, Merchandise and Business Association. Within several months, he would be promoted to manager of the association.vi

The association appears to have been something in the nature of a Black chamber of commerce and/or savings and loan. It was, in any case, devoted to the financial development of Black business enterprises. The president of the association, Rev. J. O. Thompson, described their services, and the need for their services, in a speech in 1897.

In referring to his organization, Rev. Thompson said: “Thirty-four years have passed in history and with a population of 70,000,000 in the United States, there are about 9,000,000 colored people. I believe that a solution to the negro problem lies in the fact of multiplying the race. We are accumulating &750,000,000 each year, which is distributed among the whites. The reason Bishop Turner did not get more negroes to go to Africa was due to the fact that fully $50,000,000, which reverts to the white man each year was too great an incentive to have him part with his colored brother.”

“One has said that there are 200 negroes capable of filling the presidency of the United States if it were possible to secure for a negro an election. There are about 140,000 colored people in this state, who accumulate an average of $1.75 per week. We have no manufacturing establishments of other business interests. we are unable to procure a place for one of our race in the various factories and business houses of white men, but readily spend our money with him. The negroes’ conditions to earn a livelihood are growing less each year, owing to the influx of immigrants. We must be producers as well as consumers, and although we have the same power of production, there seems to be such a lack of productive interest in us that we lose hope and fail to take courage.

“The association I represent,” Rev. Thompson continued, “is a race enterprise, and factional and denominational differences are laid aside. We all know how quickly property depreciates in value when a black man moves into a rich white settlement, and this is the reason so many of us are unable to rent houses in certain portions of this and other cities. But I must confine myself to the association. We have a capital stock of $560,000, divided in shares having a par value of $52 each. It is governed by a board of directors numbering 15 of our most prominent business men. Of the entire capital $65,000 has been subscribed and paid in.”

The Pittsburgh Press, May 25, 1897, page 9.

Alfred Cralle married Elizabeth Wade in 1900.vii They purchased a new home at 168 Mayflower Street in Pittsburgh’s East End in 1904.viii He was a member of the Golden Seal Lodge and the Free and Accepted Masons. He died at home on May 6, 1919.ix

Inspired by Evert’s advertisement, and perhaps informed by his experiences working in a drugstore and hotel, Alfred Cralle invented his version of an ice cream scoop. Evert filed an application for a patent on Cralle’s behalf on June 10, 1896. The general idea is similar to some modern scoops, the ones with a thumb-operated lever that moves a scraping blade along the inside of the scoop, to help separate the ice cream from the scooper. Cralle’s design included a similar gearing system used on many such scoops.

Cralle’s solution to the problem differed from earlier versions, while borrowing elements of those who went before. A survey of earlier patents paints a picture of the history of ice cream scoops, generally, and places Cralle’s invention in context, as one person’s small contribution, among many, to the advancement of ice cream-scooping technology.

One complaint voiced in many of the articles, posts or comments about Cralle’s ice cream scoop is that he and his invention are unknown, the suggestion being that “racism” prevented his name from being passed down to history. But none of the other people who contributed to the origin, history and evolution of the ice cream scoop are generally known either. A survey of early ice cream scoop patents adds their names to the otherwise nameless, faceless succession of inventors who did their small part to advance the art and technology of scooping ice cream.

An early patent for a designated “ice cream server” was issued to Jorge Oyarzabal, of Malaga, Spain in 1869. It included “a knife, A, and a flat scoop, spade, or blade, B, arranged at right angles to each other, and connected by a spring of elastic bow-shank, C. Or they may be connected like the legs of tongs, and be provided with a spring to open or move them apart.”

Ice Cream Server, US96929, J. Oyarzabel, October 19, 1869.

Oyarzabel’s “server” was not a “scoop” as such. But the existence of ice cream “scoops,” by that name, can be inferred from comments in Thomas Burkhard’s patent of 1875, for “vessels for measuring and handling ice-cream, &c.” The patent also succinctly describes the problem addressed by every ice cream scoop patent since - ice cream sticking to the scoop. Burkhard’s patent used thermodynamics to melt a small layer of ice cream where it touched the “vessel.”

My invention relates to an improvement in vessels for measuring, molding, and handling ice-cream or other frozen confections, whereby I obviate the troublesome freezing of the same to the sides of the vessels or molds, or whereby, when so frozen, I am enabled to melt a very thin film of uniform thickness between every part of the walls of the mold, measure, or scoop and the contained frozen cream or ice, so as to release the said frozen cream or ice, so as to release the said frozen confection from the mold without injury to the form imparted by the mold, or from the measure or scoop without the inconvenience of scraping with some instrument, as has been hitherto the case. My invention further enables me to readily mold in a neat and beautiful form and turn out upon a dish a small portion of ice-cream to be served to customers in a retail shop, a thing hitherto so troublesome and inconvenient that it has never been practiced to any notable extent.

US 165301, Thomas Burkhard, July 6, 1875 (filed May 17, 1875).

Burkhard’s patent diagram did not show a “scoop,” as such, but the patent’s language was general enough to apply to any “mold, measure, or scoop” of whatever shape or size. For whatever reason, however, Burkhard’s design does not appear to have ever been incorporated in any commercially available ice cream scoop. Perhaps the technology did not exist at the time that would have made it feasible or practical. Later patents generally focused on incorporating a scraper of some kind within the body of the scoop, to mechanically release the ice cream.

An 1878 patent to William Clewell, of Reading, Pennsylvania, introduced the internal scraping blade. The scoop required two hands to operate, one on the handle and the other twisting the internal blade using a top-mounted handle.

Ice-Cream Measure and Mold, US209751, W. Clewell, November 12, 1878.

This basic design was apparently widely used. Advertisements for conical scoops, with hand-turned knobs to operate internal scraper blades can be found well into the 1900s, and examples are easily found in online searches for “antique ice cream scoops.”

Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1906, “The Fair” advertising section.

A decade later, a man named Naylor patented something similar, but with the moving parts reversed; the internal scraping blade was connected to the main handle and remained immobile during use, whereas the top-mounted twisting handle was mounted on the body of the scooper itself - “when it is full, it is inverted and the cup turned with one hand, while the rim and knives are held stationary with the other.”

Measuring Device for Ice Cream or Other Similar Substances, US384776, T. A. Naylor, June 19, 1888.

The earliest ice scream scoop that bears a close resemblance to scoops still in use to day was patented by B. J. Noyes, of Boston, in 1895. This one has a more rounded scoop-body, with a scraping blade operated by turning a knob, that moves the blade, with a spring to move the blade back to its original position. The only thing that has changed from Noyes’ version to modern versions of the same scoop, is the mechanism used to rotate the blade.

Ice Cream Spoon, US538693, B. J. Noyes, May 7, 1895.

A different type of solution is to push the ice cream straight out from the scooper with a plunger. Older Californians might recognize the origins of the traditional, cylindrical Thrifty ice cream scoop in this patent by Hans Thode of Mattoon, Illinois.

Dipper, US554550, H. M. O. Thode, February 11, 1896 (filed July 8, 1895).

The Pittsburgh patent attorney, Henry C. Evert, began soliciting clients to submit inventions for an “ice cream disher to be operated with one hand” as early as February 1896. He continued soliciting ice cream scoop inventions for about seven years, after which another Pittsburgh patent attorney started placing nearly identical advertisements, which continued for another decade.

Evert submitted the first of his ice cream scoop patent applications in March 1896. His client, Alfred L. Riggs of Knoxville, Pennsylvania, in Allegheny County, invented a scoop with a conical body and internal twisting blades. The blades twisted when the handle was depressed or released.

Ice Cream Mold, A. L. Riggs, June 9, 1896 (filed March 7, 1896).

A couple months later, Evert’s clients, C. L. Phillis and H. E. McCoy of Pittsburgh, filed their application for a conical ice cream scoop with internally twisting blades. Their version dispensed with the spring action, using a thumb-actuated lever to twist the blade one way on one use, and be ready for use the other way for the next scoop. Their idea seems to have been to omit whatever complications or maintenance issues might be cause by spring-activated parts.

Ice Cream Mold and Disher, US568274, C. L. Phillis and H. E. McCoy, September 22, 1896 (filed May 13, 1898).

Evert’s client, Henry J. Pfeiffer of Pittsburgh, filed his application in September. His invention used a spring and plunger on top of the cone, with a screw to translate the up-down motion of the plunger into the twisting motion of the internal scraping blades.

Ice-Cream Mold and Disher, US571170, Henry J. Pfeiffer, November 10, 1896 (filed September 1, 1896).

F. D. Clark of Washington County, Pennsylvania used a completely different mechanism in his patent application, which Evert filed in March of 1896. Two hinged portions form a cone shape in its normal position. After scooping ice cream into the scooper, the user squeezes the spring-loaded handle together, forcing the two halves of the cone apart, and releasing the ice cream.

Ice-Cream Mold and Dipper, US571188, Fred D. Clark, November 10, 1896 (filed March 20, 1896).

Evert’s clients, C. W. and J. E Harmon and C. L. Boyd of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, filed an application in April of 1896 for a patent that issued on December 15, 1896. Their version of an ice cream scoop bears a close resemblance Noyes’ patent of a year earlier, and is perhaps one step closer to some scoops still in use today.

Ice-Cream Mold and Dipper, US572987, C. W. Harmon, J. E. Harmon and C. L. Boyd, December 15, 1896 (filed April 9, 1896).

Ice cream scoops with the same, general scoop design are still in use today, although perhaps with different mechanisms for operating the internal, scraping blade. Similar ice cream scoops were advertised for sale during the first decades of the 1900s.

Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama), April 18, 1908, page 18.

Henry G. Morris of Hoboken, Pennsylvania, also in Allegheny County, also received his patent in December 1896. Henry Evert had filed the application for him in September. Morris’ ice cream scoop used a thumb-actuated lever to cause the inner scraper blades to rotate within the body of the scoop.

Ice Cream Mold and Disher, US573681, H. G. Morris, December 22, 1896 (filed September 1, 1896).

John and Susanna Zimmer of Pittsburgh invented a scoop without a long handle. In its place was a looped handle, as on a coffee mug or teacup. A user depressed a button with their thumb

(against spring tension) before scooping the ice cream. After filling the scoop, they would release the button, which cause the spring to turn the internal scraping blades. Henry Evert filed their application in April of

1896; the patent issued in December.

Ice-Cream Mold and Dipper, US574185, John Zimmer and Susanna Zimmer, December 29, 1896 (filed April 14, 1896).

Henry C. Evert filed a patent application on behalf of Alfred L. Cralle of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania on June 10, 1896. His patent issued on February 2, 1897, Groundhog Day. Cralle’s invention included a bifurcated, spring-action handle. Like Naylor’s device a decade earlier, Cralle’s design called for rotating the entire body of the scooper around a stationary, internal scraping blade. But unlike Naylor’s scoop, Cralle provided toothed gearing so the scoop could be operated with one hand.

Squeezing the moving handle part (b’) against the spring tension moved a “segmental rack” (an arced section with geared teeth), which in turn engaged a “toothed rack” on the outer rim of the body of the scooper. The movement of the gearing caused the body of the scooper to rotate with respect to an interior, stationary scraping blade secured to the stationary part of the handle (b) by an arm (d). In this gripped position, a user would scoop some ice cream. When the grip was released, spring tension would move the handle back to its normally open position, which in turn would engage the gearing, rotating the scoop body back to its original position while helping release the scooped ice cream from the scoop.

The section b of the handle is provided with an arm d, extending lengthwise with the mold and secured at the apex thereof to the shaft or rivet e, on which said mold a is adapted to rotate, as hereinafter described. . . .

The portion b’ of the handle is provided on its inner end with a segmental rack h, adapted to engage with a toothed rack k, secured on the mold near the mouth of the same, and the handles are provided with a spring l, secured between the portion of the same to retract the cutters after the handles have been forced together.

Ice Cream Mold and Disher, US576395, Alfred L. Cralle, February 2, 1897 (filed June 10, 1896).

Evert filed an application for Thomas Handly of Allegheny, Pennsylvania in September 1896, for his patent which issued in July 1897. Handly’s scoop had a spring-mounted arm under a handle, which operated to sweep internal scraping blades.

Ice Cream Disher and Mold, US586181, Thomas F. Handly, July 13, 1897 (filed September 5, 1896).

James and William Crea, of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, filed their patent application on March, 1897. Their patent issued on July 20, 1897. Henry C. Evert acted as their patent attorney. The Crea’s scoop had a slide lever mounted on a spring within the handle. Pushing the lever forward activated internal scraping blades. Spring tension returned the lever to its normal position when released.

Ice-Cream Disher, US586807, James and William Crea, July 20, 1897 (filed March 29, 1897).

Evert filed an application for Thomas F. Rankin, of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in November 1896, for a patent that issued in October 1897. Rankin’s patent has a thumb-actuated lever mounted on the handle, to activate internal scraping blades within the body of the scoop.

Ice Cream Mold and Disher, US591635, Thomas F. Rankin, October 12, 1897 (filed November 6, 1896).

Evert filed an application for Herman August Weber, of Pittsburgh, in May of 1896. The patent would not issue until February of 1898. Weber’s ice cream scoop bore some similarities to Cralle’s invention. It had a bifurcated handle held normally open by spring tension, and external, toothed gearing. But Weber’s invention moved the scraping blades within the stationary body of the scoop, whereas Cralle’s moved the body of the scoop around stationary scraping blades.

Ice Cream Mold and Disher, US599157, Herman A. Weber, February 15, 1898 (filed May 4, 1896).

Three years later, another one of Evert’s clients, Maximillian Bach of Pittsburgh, patented something similar, but with the gearing engaging on the side closest to the handles.

Ice Cream Mold and Dipper, US671788, Maximillian Bach, April 9, 1901 (filed January 16, 1900).

Despite the reported “many letters from firms at Chicago, Philadelphia, Cincinnati and other cities offering large inducements to him should he wish to sell the patent outright or on a royalty,” it is not clear whether Cralle’s design was ever put into production. Some posts about Cralle’s invention include photographs of what they believe to be a version of his ice cream scoop design, but a close look at the mechanism proves otherwise.

Samuel Momodu’s article on blackpast.org, “Alfred L. Cralle (1866-1920),”x for example, includes a photograph of an ice cream scoop with a mechanism for turning interior scraping blades within a stationary scoop body, not the other way around, as claimed and described in Cralle’s patent. The photograph posted in that article shows what antique ice cream scoop dealers refer to as “Gilchrist’s No. 33 Ice Cream Scoop.”xi

The Southern Pharmaceutical Journal, Volume 3, Number 7, March 1911, (insert) page 33.

Images of “Gilchrist’s No. 33 Pyramid Shaped Ice Cream Disher” reveals a thumb-operated lever that pushes a rod forward, the rod having a rack which engages with gearing on top of the internal scraping blade, to turn the blades and release ice cream scooped into the body of the scooper.

This model is apparently based on a patent for an “ice cream ladle,” issued to Raymond B. Gilchrist, of the Gilchrist Company of Newark, New Jersey. The patent describes a “rack bar” with “teeth” which engage a “pinion” to turn an internal “scraper.”

Ice Cream Ladle, US1109577, Raymond B. Gilchrist, September 1, 1914 (filed April 16, 1910).

Gilchrist is a rare bird among ice cream scoop inventors. He is one of a small group whose name is known to history, at least among a small cadre of dedicated ice cream scoop collectors who share their passion on scoopcollector.com. Gilchrist was a serial inventor, entrepreneur and businessman. He held patents on numerous bar, soda fountain and kitchen-related items, including drink mixers, glass holders, lemon squeezers, corkers, cork extractors, battler cappers, mop wringers and ice cream scoops. Several of Gilchrist’s non-ice cream designs are still familiar-looking items, nearly unchanged in more than a century, including his “mop press,” “straw dispenser” and electric ice cream drink mixer.

Raymond Gilchrist and two partners organized The Gilchrist Company of Newark, New Jersey in January 1910, with capital of $125,000, and the stated objective of “manufacturing cork pullers, lemon-squeezers, corking machines, capping machines, ice pics, ice tools, etc.”xii

The company would also sell a line of ice cream scoops, several of them based on patents of his own design. Gilchrist’s No. 30, for example, looks like the “ice cream disher” in another one of his patents. This model reminds me of the mashed-potato scoops used by lunch-ladies in the schools I attended in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Southern Pharmaceutical Journal, Volume 3, Number 7, March 1911, (insert) page 33.

Ice Cream Disher, US1109576, September 1, 1914 (filed September 26, 1907).

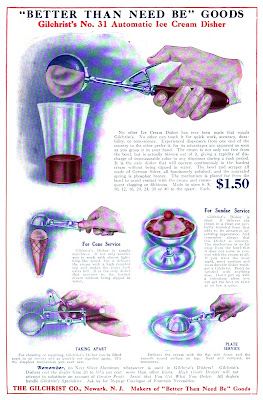

Gilchrist’s No. 31 Automatic Ice Cream Disher looks like the design disclosed in another of his patents. This design looks very much like many ice cream scoops still in use today.

The Southern Pharmaceutical Journal, Volume 3, Number 7, March 1911, (insert) page 33.

US1132657, Raymond B. Gilchrist, March 23, 1915 (filed February 3, 1908).

Another inventor whose name is known among ice cream scoop collectors, and whose scoops are sought after by ice cream scoop collectors today, is Edwin Walker, of Erie Pennsylvania. Walker was associated with the Erie Specialty Company, which had its own line of ice cream scoops. Like Gilchrist, Walker held numerous patents, including several cork-pullers, several cigar-tip cutters, several phonographs, and several ice cream scoops. The Erie Specialty Company sold several different ice cream scoop designs under the name, “Walker’s ‘Quick and Easy’ Soda Fountain Accessories.” They also sold other of Walkers’ inventions, including an “automatic cork-puller.”

One of Walker’s early ice cream scoop patents introduced the “rack” and “pinion” mechanism, later adapted, albeit in a different arrangement, in Gilchrist’s No. 33 and shown in Gilchrist’s ’577 patent. Walker’s early scoop had a “rack” G with “rack teeth” g which engage a “pinion” F to rotate the “scraper” C within the body of the scoop.

Ice Cream Dipper, US892633, Edwin Walker, July 7, 1908 (filed December 1, 1905).

One of Walker’s later patents showed an operating mechanism eerily similar to Gilchrist No. 33 and and the ’577 patent, but Walker's application was filed several months later than Gilchrist’s.

Ice-Cream Disher, US1162116, Edwin Walker, November 30, 1915 (filed July 19, 1910).

Walker’s ’116 patent is reflected in the Erie Specialty Company’s “Walker’s Quick and Easy Soda Fountain Accessory” No. 387.

Other of Walker's designs looked, more or less, like other of his ice cream scoop patents.xiii No. 389 looked like his patent “ice cream disher,” US1138706, May 11, 1915, and No 386 like his patent “ice cream dipper,” US1012944, December 26, 1911.

Walker’s No. 385 looked like his .

Walker’s No. 182 and No. 184-A looked like one aspect of Walker’s patent “ice cream dipper,” US1138704, May 11, 1915, as as shown in figures 4 and 5 of the patent. This design hearkened back to Clewell’s 1878 patent, in general look and operation, but with a newly designed method of attaching the turn-key to the apex of the scoop.

Ice Cream Trade Journal, Volume 9, Number 4, April 1913, page 13.

The final coup de grace (or would that be coup de glace?) in the ice cream scooper-stakes was, perhaps, the simplest, most elegant solution - no mechanism, just thermodynamics, courtesy of Sherman Kelly and the Zeroll Company.

This so-called “antifreeze” scoop reportedly eliminated ice pellets on the surface of the serving. I believe that some accredited it with non-stick characteristics. It is very easy to use. It is easy to clean, It is robust. It is to this day one of the most commonly used ice cream scoops. To some extent, this scoop ended the race to find the best tool for serving ice cream. Did I mention that it is plain and does nothing but serve ice cream?

“Mechanisms,” scoopcollector.com Blogs, https://www.scoopcollector.com/mechanisms.

In 1939, Sherman L. Kelly, of Toledo, Ohio, received a patent for an ice cream scoop that keeps itself just above the melting point of the ice cream, which “lubricates” the scoop so that the scoop of ice cream “quickly and freely slides into the bowl from the severing rim and as freely is released therefrom.”xiv This was a simplification over his earlier patent which used electrical heating elements embedded within the scoop.xv

But even Kelly borrowed, perhaps unknowingly, from an age-old solution. In 1875, Thomas Burkhard of New York City patented a vessel for handling ice cream that anticipated the thermodynamics of the Zeroll scoop by nearly six decades.

Burkhard's patent used water, even cold water.

The cold water, when the measuring-vessel is filled with frozen cream, parts enough of its specific heat to melt a uniformly thin film between all parts of the wall of the vessel A, and thus to release the cream from the vessel, and permit the frozen confection to be turned out neatly and quickly into the vessel of the purchaser. I keep the cold water in this measuring-vessel as long as I wish without changing. It acts perfectly at any moderately low temperature above 32 deg. Fahrenheit, quickly regaining from the surrounding air the small amount of heat it loses in melting the film which releases the cream from the vessel A.

US 165301, Thomas Burkhard, July 6, 1875 (filed May 17, 1875).

Kelly's patent used liquid within the scoop, alcohol or water, but any liquid having a "high heat conductivity."

It thereby conducts heat from the hand of the operator through the walls of the handle into the liquid. In practice this is normally a sufficinet temperature rise to maintain the face above the freezing temperature of the material. This lubricates the tool so that the formed service portion quickly and freely slides into the bowl from the severing rim and as freely is released therefrom.

US 2160023, Sherman Kelly, May 30, 1939 (filed May 23, 1935).

The “stopper” E of Burkhard’s invention corresponds to the “plug” 10 of Kelly’s. It’s mostly the shape of the two vessels that distinguishes them one from the other. Burkhard’s patent diagrams illustrated something more like a cup or tub of ice cream, but the language of the patent was very general, and even on its own terms applicable to any vessel, “mold, measure or scoop” of any desired shape or size.

Perhaps the technology did not yet exist for producing practical ice cream scoops embodying Burkhard’s idea at the time. In any case, we should ball be grateful that the technology did exist when Sherman Kelly, as legend has it, witnessed a young woman blistering her hands while scooping ice cream in West Palm Beach, Florida in 1932.xvi

National Ice Cream Day is the third Sunday in July. Perhaps February 2nd can be turned into National Ice Cream Day, to remember all of the inventors, from A to Z (Allegheny to Zeroll), and from Oyarzabel and Clewell to Gilchrist and Walker, and all of the Cralles and others in between, who advanced the art of scooping ice cream.

If the groundhog does not see his shadow, summer - and ice cream weather - will arrive six weeks early.

Ice Cream Trade Journal, Volume 9, Number 4, April 1913, (insert), page 17.

i The Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1897, page 10.

ii Pittsburgh Daily Post, July 25, 1900, page 5.

iii A couple other local patent attorneys also filed similar patents for other western Pennsylvania inventors, perhaps inspired by Evert’s ads, and Evert himself filed a few more ice cream scoop patent applications a few years later.

iv The Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1897, page 10.

v Pittsburgh Dispatch, April 14, 1892, page 3 (“Boy about 17 or 18 years old to attend soda fountain. Markell Bros., Penn and Frankstown avenues.”).

vi The Pittsburgh Press, February 14, 1897, page 10.

vii “Marriage Licenses,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, September 21, 1900, page 5.

viii Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, November 17, 1904, page 16 (Mayflower street: Matthew H. Patton sold to Alfred L. Cralle an improved lot, 23x100 feet, in Mayflower street, near Park avenue, Twenty-first ward, for $2,700).

ix Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 9, 1919, page 15 (“On Tuesday, May 6, 1919, at 3 a.m., Alfred L. Cralle, beloved husband of Elizabeth L. Cralle, at the family residence, 168 mayflower street, East End”).

x https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/cralle-alfred-l-1866-1920/

xi Searching online for “Gilchrist’s No. 33” or “Gilchrist conical ice cream scoop” or the like results in numerous hits for images of scoops similar to the one shown.

xii Newark Evening Star and Newark Daily Advertiser, January 11, 1910, page 15.

xiii Ice Cream Dipper, US1012944, Edwin and Clarence Walker, December 26, 1911; Ice Cream Disher, US1138706, Edwin Walker, May 11, 1915; Ice Cream Dipper, US1138704, May 11, 1915

xiv Tool for Handling Congealed Materials, US2160023, Sherman L. Kelly, May 30, 1939 (filed May 23, 1935).

xv Gathering Tool for Congealed Material, US1974051, Sherman L. Kelly, September 18, 1934 (filed April 14, 1933).

xvi “Our History,” zeroll.com, https://zeroll.com/pages/about-us

.jpg)

%20-%20Copy.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment