|

| Everett Bird Mero, American Playgrounds, their Construction, Equipment, Maintenance and Utility, Boston, Massachusetts, The Dale Association, 1909, page 66. |

PLAYGROUND SONG

In friendly feats of skill we vie

As o’er the Maypole rope we fly,

Or balance in the tossing swing,

Or on the see-saw lightly spring.

We cluster on the giant stride,

And gaily coast on Kelly’s slide,

And, upside down, we face the stars

Upon the horizontal bars.

. . .

Playground fun and playground ways

Make for children merry days.

So we sing our playground song,

Happy as the day is long!

-G. F. P., in the

Philadelphia Record

Playgrounds

and playground slides were both well established features of pop-culture when

the poem was published in the Brooklyn

Daily Eagle in 1911.[i]

Things were

different in Brooklyn two decades earlier when electric trolleys first plied

the streets of Brooklyn:

Little Zetta Lumberg, aged four, was this morning said to be

dying at St. Mary's Hospital, Brooklyn. She was knocked down by trolley

car No. 118, of the Fulton street line, last night.

As the child crossed the street at Saratoga avenue there was a maze of trolley cars and vehicles. She dodged behind an uptown car just as another trolley car came flying down the other track.

As the child crossed the street at Saratoga avenue there was a maze of trolley cars and vehicles. She dodged behind an uptown car just as another trolley car came flying down the other track.

The

Evening World (New York) October 3, 1893.

|

| The World (New York), February 27, 1895. |

The new-fangled

vehicles brought speed and danger to the streets, a place that previously had

been a relatively safe space shared by horse-drawn wagons, pedestrians, and children

at play. The Los Angeles Dodgers’ nickname,

shortened from the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers (first used in 1895), is a lasting

reminder of those dangers. See my earlier piece, The Grim Reality of the “Trolley Dodgers.” [ii]

One solution

to the problem – playgrounds:

Those children of Brooklyn who survive the attacks of the

remorseless trolley car will at least have pleasant play-grounds next summer.

New York Tribune, October 8, 1893, page

6.

As the

electric trolley spread to other cities, playgrounds were never far

behind:

[I]n the spring of 1895, the trolley system was adopted in

Philadelphia, and many accidents to children playing on the streets stimulated

the public sentiment very greatly in favor of playgrounds were “the poor little

urchins could play, free from danger to life and limb.”

Stoyan Vasil

Tsanoff, Educational Value of the

Children’s Playgrounds, a novel plan of character building, Philadelphia,

1897, page 136.

In 1899, the

Mayor of Toledo, Ohio waxed philosophical about the need for more playgrounds

and better playground equipment:

I want to give them places where they may play free from the

electric cars and the temptations of the street, where they may get together

and learn to love each other. It is true

that in many of our cities certain parts of the parks have been designated as

playgrounds for the children: but, as a rule, they have not been equipped with

apparatus and are nothing more than places where children might romp and play ball,

etc. But, with the closing years of this

century, we catch glimpses of the new civilization that is to characterize the

twentieth century. We are looking

forward and thinking of a larger life that refuses to be satisfied with the

sordid scramble or possession of property and demands opportunity for

expression of men’s spiritual nature that has been in danger of being crushed

out by the fierce warfare of competition that is now giving way to a more

sensible order of combination, which, in turn, is to be succeeded by a

co-operation that will lead to brotherhood, a brotherhood that is to make it

its business to see that the possibilities of happiness be within the reach of

every man, woman and child – in short, to see the kingdom of heaven set up and realized

on earth.

The North Adams Transcript (North Adams,

Massachusetts), August 12, 1899, page 2.

A bit

overwrought, perhaps, but the kingdom of heaven on earth sounds like a worthy

goal, regardless of one’s religious bent.

But Mayor Alanson Wood was a man of his time, and his time was defined

by the

progressive movement, which swept the country from the 1890s through about

the 1930s. The progressive movement, in

part a reaction to industrialization and urbanization, was marked by broad efforts

to improve living conditions, public health and safety, and working conditions.

One aspect

of the progressive movement were so-called “settlement

houses,” a worldwide network of charitable, neighborhood social work

institutions, hundreds of which were scattered across the country and

throughout the world at the turn of the century:

Settlements were organized initially to

be “friendly and open households,” a place where members of the privileged

class could live and work as pioneers or “settlers” in poor areas of a city

where social and environmental problems were great. . . . The idea was that

university students and others would make a commitment to “reside” in the

settlement house in order to “know intimately” their neighbors. The primary

goal for many of the early settlement residents was to conduct sociological

observation and research. For others it was the opportunity to share their

education and/or Christian values as a means of helping the poor and

disinherited to overcome their personal handicaps.[iii]

One such

“settlement house” was Washington DC’s “Neighborhood House,” where an anonymous

janitor designed and built the first known children’s playground slide sometime

between its opening in April 1902 and August 1903, when the earliest known

reference to a playground slide appeared in print:[iv]

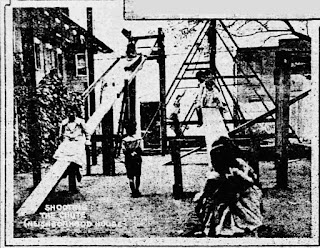

“Shooting the Chutes.”

One of the most delightful sports in this playground is

“shooting the chutes,” a piece of apparatus invented and installed by “Uncle

Richard,” the colored janitor of Neighborhood House, who takes as great delight

in the pleasures of the little folks as they do themselves. The “chutes” consists of a long, smooth

plank, the lower end about twelve inches from the ground and the other placed

at an elevation of about twelve feet.

There is a platform at the top of the chute, which is reached by means

of a ladder. The children climb up the

ladder and seating themselves on the smooth, sloping board, slide to the bottom

with greater or less speed, holding onto the slide railing which has been

erected along the course to prevent accidents.

It is a thrilling slide and one greatly enjoyed, even by older people.

|

| Evening Star (Washington DC), August 1, 1903, page 7. |

And if

playground safety was the goal, some playground equipment of the period seems

to have missed the mark, at least as viewed from the perspective of our more

safety conscious era, with our plastic “play structures” and rubberized

playground surfaces.

One early

example of retrospectively obviously dangerous playground equipment appeared in

Boston a few months before Washington DC’s more conventional playground slide –

the sliding bars.

|

| Boston Post, May 3, 1903, page 7. |

A

description of the use of similar sliding bars in Washington DC a year later

illustrates the potential for injury:

At one place where there are sliding poles – that is, two

long smooth poles set a couple of feet apart and forming the base of a right

angle between the ground and a platform about twelve feet high – some feats

were performed that were truly spectacular.

One favorite “stunt” seemed to be the trick of standing on the platform

and jumping out about six feet into space, catching by arms and legs on the

pole, the body between, and sliding swiftly to the bottom. This was done time and again, but, curiously

enough, without mishap. One of the boys

had a trick of sliding halfway down and continuing the descent by means of a

series of somersaults. He would land on

his head two times out of three, but a small matter like that did not seem to

feaze him.

Washington Times, September 11, 1904,

part 3, page 9.

The national

reach of the “settlement house” and playground movements made it possible for a

good idea in one city to be copied in another city; but which slide was

first? Boston’s “sliding poles” fell

squarely within the range of time during which “Uncle Richard” could have

designed the first conventional playground slide in Washington DC, thereby complicating

the question. The appearance of another

type of slide during the same period of time complicates the question even

further.

And, in a

touch of irony, the dangerous trolleys that a decade earlier had prompted the

need for more playgrounds for children of poor and working class families, and

thereby resulting in the invention of the playground slide, also provided

easier access for those same poor and working class families to visit “the

biggest playground in the world,”[v]

Coney Island, where increased attendance spurred the creation of more and

better attractions – including “Kelly’s Slide.”

Amusement Park Slides

On opening

day of Coney Island’s new Luna Park attraction on May 16, 1903, visitors were mesmerized

and enthralled by its electric lights – and thrilled to its new rides, including

a slide:

They have created a realm of fairy romance in colored light,

so beautiful that the rest of Coney Island will have to clean up and dress up,

if it is to do business. . . . [T]he beauty of the place under its

extraordinary electrical illumination scheme is its primary feature.

. . .

In one corner of the grounds is a quaint old Dutch windmill,

and here was discovered one of the most popular contrivances for amusement ever

seen. It consisted of a bamboo chute with a good sharp incline, but with

many devious turnings, and just broad enough for a good-sized boy. It was not an hour before an unnumbered host

of boys had discovered this wonderful slide, and before many minutes boys were

shooting down this chute at the rate of about three a second, and fairly

smoking as they slid down the curves.

The chute has not yet been worn smooth as glass, as it will be soon, and

last night it was estimated that something like 3,000 pairs of trousers were

more or less damaged within the short space of an hour. It was great fun.

The New York Times, May 17, 1903, page 2.

Young boys

were not the only people who enjoyed the “Helter Skelter” or “Kelly’s Slide”:

|

| Colliers , Volume 33, August 27, 1904, page 20. |

“Kelly’s

Slide” was so successful that they installed a new slide the following year – this

time with bumps:

Gov. Odell Bumps the Bumps and Shoots the Chutes at Coney

Island

|

| Evening World (New York), July 22, 1904, page 3. |

|

| New York Times, June 12, 1904, page 25. |

Although it

is uncertain whether Boston’s sliding poles, Coney Island’s “Kelly’s Slide” or “Uncle”

Richard’s “chute the chutes” was first, there may have been some earlier slides.

A brief

notice in a St. Louis newspaper from 1901 refers to two attractions that sound

like slides:

Summer Garden Arrangements.

New attractions on the Midway will be seen. . . . The moving stairway, Kelly

Slides and cellar door will be included among the other features.[vi]

There may

even have been some sort of children’s slide in the Children’s Pavilion of the

1893 Chicago Worlds Fair, the fair that put the “Midway” in fairs :

One of the charming sights seen here [(the Children’s

Pavilion)] was a little red-cheeked English miss, whose stockings reached half

way to her bare knees, and who, after long persistence, succeeded in “placing

the cart before the horse,” rumbling her wagon in front of her, as she slid down the shining “cellar door.”[vii]

So what was

this “cellar door”?

The

quotation marks suggest that it was something other than a literal cellar door. The description of the “cellar door” as

“shining” may refer to something “polished smooth as glass,” as was the

“Kelley’s Slide” at Coney Island several years later.[viii] One chronicler of the fair described the

Children’s Pavilion as “the biggest playhouse in the world” with “toys of all

nations, from the rude bone playthings of the Eskimo children to the wonderful

mechanical and instructive toys of modern times,”[ix]

which suggests that this “cellar door” may well have been something

purposefully designed for children to slide on.

The truth is

out there, but we may never know the answer.

It is also

possible that the “cellar door” at the Children’s Pavilion was an actual,

typical American cellar door, installed with the express purpose of having children

to slide on it, as generations of American children had been doing for decades.

|

| The Herald Los Angeles, June 21, 1896, page 13. |

Cellar Door Nostalgia

Early

playground slides and amusement park slides were frequently compared with

inclined cellar doors, like the one Dorothy tried getting into to escape the

twister in The Wizard of Oz.

This fall he is going to have an entirely new list of

attractions. Chief among these will be a

tobogganless toboggan slide. It is a

contrivance similar to the one known as “bumping the bumps” at Coney Island. .

. . No cars are provided for the slide,

the venturesome passenger merely sitting down in it and sliding over the route,

just as we used to do in childhood’s happy days on the

old cellar door.

The L’Anse Sentinel, (L’Anse, Michigan),

September 17, 1904, page 1.

American

children were sliding down cellar doors as early as the summer of ’42 (1842):

But there is one grievance which clearly demands the

concentrated energies of the whole civil – and, if it must be so, in the last

resort, military – power of our city for its eradication – we mean the “rowdy

boys,” from three to ten years of age, who “deface our fences” with chalk and

pencil, “injure our palings,” by riding on them, drag their miniature engines

[(wagons)] upon our sidewalks, play “tag” up and down our alleys, perch

themselves upon our stoops, and slide down our

cellar-doors.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 16,

1842, page 2.

The joys of

sliding on cellar doors inspired a

popular song entitled “Grimes’ Cellar Door” and a stage play of the same name

that ran for decades.

The popular song

“Grimes’ Cellar Door” debuted in 1870:

For I would give all my Greenbacks,

For those bright days of Yore,

Old Grimes’ Cellar Door.

The play made its debut at Proctor’s Opera House in Wilmington, Delaware in

August 1890. Grimes Cellar Door ran continuously, in one form or another, for more than a decade;

frequently put on by small touring companies playing small towns.

|

| Pittston Gazette (Pittston, Pennsylvania), December 23, 1910, page 3. |

By 1897,

sliding down the cellar door was considered one of those nostalgic pleasures of

lost youth:

But of all sliding places the most delightful, beyond a

doubt, is the cellar door. There are

many reasons for this, which will appear upon a moment’s consideration.

In the first place, the cellar door stays put; you don’t have

to be forever fixing it, as you do the chair and the ironing board. It is outdoors, in the open air, an added

delight. It draws other children, who

come to play with you, to slide on your cellar door, or it may be that you go

to slide on theirs; the cellar door is perhaps the scene of your first

introduction into youthful society.

There are cellar doors everywhere, but the outside, inclined

cellar door, of the kind that you slide on, is peculiar chiefly to smaller

cities, to towns and villages and to houses in the country; to localities where

there is room. . . .

Blessed is he among whose earlier recollections is a cellar

door, with the bright blue sky above and green grass to roll upon all around.

The Salt Lake Herald (Utah), August 1,

page 14.

The

expression “cellar door,” and its association with childhood play, was used

idiomatically in circumstances where we might use “plays well with others” or

“takes his ball and goes home,” as the case may be.

What the Monroe Doctrine Means.

Burlington Hawkey.]

The Monroe doctrine simply and explicitly declares that no

foreign nation shall come over here and slide down our

cellar door. . . .

Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee),

April 12, 1880, page 2.

The Pittsburgh Times mustn’t let its Washington correspondent

speak of “a man named Miller” in connection with the Internal Revenue

Commissionership. He doesn’t slide on our political cellar-door, and we

have at times refused to spin tops with him for keeps; but he isn’t altogether

unknown in Washington and is very far from being a nobody.

Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (West

Virginia), March 16, 1885, page 1.

Now that Prince Bismarck has apologized and declared that the

Samoa incident was all a mistake, we freely forgive him, and he may slide down our cellar-door whenever he chooses,

just as if nothing had happened. – Chicago

News.

The Vermont Watchman (Montpelier,

Vermont), May 1, 1889, page 4.

|

| Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), November 6, 1895, page 6. |

|

| Semi-Weekly Independent (Plymouth, Indiana), April 22, 1896, page 5. |

|

| Star Tribune (Minneapolis, Minnesota), October 12, 1902, page 41. |

A few years

later, the expression “cellar door” first became known as the most beautiful

expression in the English language.

Coincidence? Cause and Effect? You be the

Judge.

See, for example, “Cellar

Door”, Grant Barrett, The New York Times

Magazine, February 11, 2010 (tracing the idea that “cellar door” is an

inherently beautiful, sonorous or euphonous expression to 1903) and “Slide Down My Cellar

Door,” Geoff Nunberg, LanguageLog, March 16, 2014 (speculating that the

perceived special beauty of “cellar door” may have been influenced, in part, by

the “cellar door” songs and their romantic, nostalgic associations).

I will save

that question for another day.

More Slides

But as

popular as cellar door-sliding was before 1903, it quickly gave ground to the

modern playground slide.

There were

playground slides in Chicago by 1905:

St. Louis

had a new “Slide, Kelly, Slide” in 1908:

A constant line of youngsters stood awaiting their turn at

the “Slide, Kelly, Slide,” a contrivance constructed

on the principle of the shoot-the-chutes.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), June

15, 1908, page 4.

The new

“Kelly Slide” was front-page news in Kansas in 1913:

|

| The Junction City Daily Union (Kansas), April 28, 1913, page 1. |

Soon, you could

buy your very own “Kelly Slide” so that your children wouldn’t have to mix it

up with the riff-raff down at the public park:

The common

names, “Slide, Kelly, Slide” or “Kelly Slide,” refer to an earlier pop-culture

phenomenon, the song, “Slide, Kelly, Slide.” The song, one of the first big hit

songs recorded on a phonograph, was itself a reference to an

earlier sports and pop-culture icon, “the Only” Mike “King” Kelly, a popular

vaudeville performer and professional baseball’s first $10,000 man.

Mike Kelly

was an aggressive base-runner and known, along with his other Chicago

teammates, as a good slider. The hook

slide, or “Chicago slide,” originated in Chicago while Mike played there. However, the “slide” of “Slide, Kelly, Slide”

fame may be more of a dig at his leaving Chicago for Boston, and later breaking

a contract to go on an Australian baseball tour with the Chicago team

(“sliding” being a euphemism for breaking a contract or getting out of an

obligation), than it is a reference to base sliding. The timing, circumstances, and lyrics of the

song suggest as much. He may have only

become famous for his sliding retroactively, in the afterglow of the song that

firmly associated his name with sliding.

Slide, Kelly, Slide!

Mike Kelly is

a hall of fame catcher who played seventeen seasons of professional

baseball. He first rose to prominence as

a member of the Chicago White Stockings in 1880. He played for seven seasons, much of that time

under owner Albert Spalding; yes, that Spalding, who is now better remembered

for is sporting goods company which is still in business today.

Following

the 1886 season, Kelly announced that he would never play in Chicago

again. He claimed to have been

improperly fined $275 for “intemperance” (drinking too much). He and his brother were doing well in the

horse business at Hancock Park, Chicago, and he didn’t need his baseball money. To recoup on his investment, Spalding sold

Kelly’s contract to the Boston Beaneaters for a then unimaginable sum of money

for a baseball player - $10,000.

In 1888,

Albert Spalding organized an Australian baseball tour in which his Chicago

White Stockings played a series of exhibitions against a team of all-stars from

other teams. He called the all-star team

the “All-American Baseball Team,” which is believed to be the origin of the now

common expression or designation, “All-American”. The teams left Chicago in late-October and

played a series of games across the country, en route to its port of departure,

San Francisco.

Mike Kelly

initially agreed to join the “All-Americans”. His image appears on promotional material and

was prominently mentioned in the pre-tour publicity campaign.

|

“The All-American

Team” (Mike Kelly, top row-center), Outing, Volume 13, Number 2, November

1888, page 160.

|

His team was

glad to see him go on tour, for reasons that lend credence to Spalding’s

reasons for fining Kelly two years earlier:

President Soden of the Boston club says he is glad Kelly is

going to Australia this winter, for he will have no opportunity to carouse with

his Boston friends.

Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1999, page

13.

But as the

day of departure grew near, Kelly was nowhere to be seen – and rumors started

circulating that he was not going to make the tour.

|

| St Louis Post Dispatch (Missouri), October 11, 1888, page 8. |

Tiernan and Mike Kelly still say that they are not going to

Australia. The two Kellys - $10,000 Mike

and Umpire John – are to open a saloon in New York this winter.[xiii]

Despite the

rumors, numerous newspapers ran articles assuring that Mike Kelly was on his

way, would be there in a few days, or would catch up with the team soon. The news of his imminent arrival followed the

team on its cross-country tour from Chicago to San Francisco, in a kind of

running gag that would have done Chevy Chase (and his “Generalissimo Francisco

Franco is still dead bit”[xiv])

proud.

When Kelly’s

name showed up on pre-printed scorecards in Minneapolis, the backup catcher pretended

to be Kelly. But they still expected him

in Cedar Rapids.

The boys have been having a laugh about it ever since, and

will have lots to tell Kelly when he joins us.

Evening World (New York), October 23,

1888, page 1.

Or at least

in Salt Lake City a week later.

The absorbing conundrum with Mr. Spaulding, Mr. Anson and the

Australian contingent last week, was: “will Kelly go with us to Australia,” as

rumor had it that Kelly was about to jump his contract

at the last minute. Mr. Spaulding

was confident, however, that the “great beauty” would show up at the eleventh

hour, and latest accounts have it that Kelly is now with the team, and will surely be here on October 31st and November 1st.

The Salt Lake Herald, October 24, 1888,

page 5.

|

| The Sunday Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), November 4, 1888, page 6. |

But surely

he wouldn’t miss the boat, even after missing a game in San Francisco:

Mike Kelley, the beauty, will arrive in this city

in a few days. He will accompany Spalding’s players to

Australia. It looks as if Mike was

afraid of a California audience. Perhaps

he has recollections of his work in San Francisco last season.

Oakland Tribune (California), November

14, 1888, page 3.

One day

before his ship sailed out of San Francisco, some papers were still reporting

his imminent arrival.

|

| Fisherman and Farmer (Edenton, North Carolina), November 16, 1888, page 3. |

The joke

followed him into the next season. At

the end of the 1889 season, Boston treated Kelly to a big party at which he was

presented with a Charlotte Russe (a

type of cake) in the shape of a giant tureen:

On the cover was the inscription “Slide, Kelly, slide!” and

below this on the other side of the tureen were the words, “Where is he?”

The Evening World (New York), October

11, 1889, page 1.

The song

“Slide, Kelly, Slide” was first performed in Chicago in early November, 1888, less

than two weeks after he missed the train out of Chicago with his

Australia-bound, All-American teammates, and about two

weeks before the ship sailed for Australia.

Although the song would later be associated with (and the sheet music

dedicated to) the singer, Maggie Cline, the song was first performed by its

writer, comic actor J. W. Kelly (no relation), the “Rolling Mill Man.”

|

| Chicago Tribune, November 5, 1888, page 3. |

This first

notice refers to a “great hit,” which at first blush might suggest the song has

been around for awhile. But a paper trail of his performances in and

around Chicago during the weeks leading up to this earliest notice never mention the song.[xv] An advertisement for his performance at the

Park Theatre just two days earlier also does not mention the song, suggesting that the song was new, or least relatively new, in early November 1888;

in the same place and time where Mike Kelly was skipping out on his Australian tour commitment.

And what’s

more, some of the lyrics arguably relate to Mike Kelly’s life and career, while curiously avoiding any praise for Mike Kelly and his purported sliding skills.

In the first

verse, Kelly strikes out, but has a chance to get on base when the catcher

muffs the ball. The chorus encourages him

to:

Slide, Kelly, slide,

Your running’s a disgrace,

Slide, Kelly, slide!

Stay there, hold your base!

If someone doesn’t steal you,

and your batting doesn’t fail you,

They’ll take you to Australia!

Slide, Kelly, slide!

In the

second verse, Kelly goes into the game to replace a catcher who “went to get a

drink.” Poor Kelly can’t see the ball and

gets his “muzzle” broken. Cue the chorus.

In the

third, they send him out to center field despite his rapidly swelling nose. It doesn’t go well, and he doesn’t’ remember

what happened. When he regains

consciousness as they carry him home, he learns that they lost the game

62-0. “Slide, Kelly, Slide! etc.”

So the song

is largely nonsense and isn’t clearly about Mike Kelly. The song was written and first performed by a

singer named Kelly, so perhaps it was merely eponymous.

The lyrics do not reflect a great baseball player or runner. The words of the chorus encourage him to

slide, but he is always in trouble and never quite succeeds.

Some

aspects of the lyrics, however, arguably relate to Mike “King” Kelly. There is a catcher who drinks, his “running is a

disgrace,” and “if someone doesn’t steal him” they might take him “to

Australia.” The song debuted during the week in which Mike Kelly, a professional

baseball catcher and notorious drinker, famously skipped out of his contractual

agreement to go to Australia in the city and with the team from which

he was famously “stolen” by Boston two years earlier.

A slang

dictionary of the time reveals that the verb, “slide,” then as now, could be

used to mean leave, skip, shirk – all words that a Chicagoan might have used

with respect to Kelly’s leaving Chicago and skipping his promised trip to

Australia.

|

| John S. Farmer, Slang and its Analogues, Volume 6, 1903. |

To my mind,

the circumstances suggest that the song was at least as much about his leaving

Chicago and skipping the trip to Australia, as it is about his prowess as a base-runner. And in any case, there is very little

contemporary evidence that he was widely known or regarded as a particularly

skillful base-slider.

I could not

find any contemporary evidence that he was particularly well-known for sliding

before 1889. But in May of

1888, a mere five months before the song first appeared in Chicago, a newspaper published a two-column, page-length analysis of the dangers

of baseball sliding, including an analysis of the distinct sliding styles of several players.

He must sprint away when opportunity offers, and by throwing

himself head foremost or feet foremost to the earth, slide along the ground

towards the goal, over pebbles and through mud and dust, only to be greeted

with laughter if unsuccessful, and with mingled laughter and applause if

successful. Barked shins, torn scalp,

bruised limbs and body he gets for his daring, and very little else. . . .

The best sliders . . . prefer the headlong plunge, Johnnie

Ward, Ned Williamson, Fogarty, Ewing, Sunday, Mulvey, Nash, Brown of

Boston. Latham, Dave Orr, McClellan and

others equally as well known go in head foremost, while “the only” Kelly, Gore, Connor, Smith, Robinson, Bastian, Anson,

Hanlon and others prefer jumping feet foremost.”[xvi]

The article

details the base-running idiosyncrasies of several players, including Orr,

Easterbrook, Williamson, Ward, Ewing, Latham, Connor, Hanlon, Fogarty, Sunday

(Billy Sunday who, decades later, famously

couldn’t shut Chicago down) and Brown; with no mention of anything peculiar

or particularly interesting about Mike Kelly’s slide.

I could find

only one oblique reference to Kelly’s slide from his time in Chicago; a

humorous anecdote originating in Chicago used the expression, “Chicago slide”,

idiomatically in reference to a disheveled person.

In the

story, a bloody passenger boards a train.

His “trousers looked as if he had made a Chicago slide for third base

through a briar patch.” When pressed

about why he looks so bad (had been in an railroad accident? – no; was he a

runaway? – no; was he a baseball player? – no), he responds with a passive-aggressive

threat; “I tried to stick my nose into another man’s business.”

|

| The Woodstock Sentinel (Woodstock, Illinois), August 27, 1885, page 6 (reprinted from the Chicago Herald). |

Years later,

“Chicago slide” and “Kelly’s slide” appear more regularly in print with

reference to the hook-slide in baseball.

|

| John J. Evers, Touching Second; the Science of Baseball, Chicago, Reilly and Britton, 1910, page |

The best

evidence that Kelly was, in fact, known for developing a unique style of sliding

appeared a couple decades later.

Kelly invented the “Chicago slide,” which was one of the greatest tricks

ever pulled off. It was a combination

slide, twist and dodge. The runner went

straight down the line at top speed and, when nearing the base, threw himself

either inside or outside of the line, doubled the left leg under him (if

sliding inside, or the right, if sliding outside), slid on the doubled up leg

and hip, hooked the foot of the other leg around the base and pivoted on it,

stopping on the opposite side of the base.

Every player of the old Chicago team practiced and perfected

that slide and got away with hundreds of stolen bases when really they should

have been touched out easily.

Los Angeles Herald, June 10, 1906, page

8.

The same

article claimed that only one man could still do the “Chicago slide” to perfection;

Bill Dahlen, then of the New

York Giants. A few years later, when he

was the manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Dahlen wrote an article in which he

explains that he learned the slide directly from Kelly’s old teammates in

Chicago:

Another thing they taught me was sliding to bases, not only

so as to avoid being touched, but also to avoid getting hurt or hurting anyone.

That slide known as the “Chicago

slide” was the invention of Kelly and adopted by Burns, Williamson,

Pfeffer and the great players of that day.

The Akron Beacon Journal (Ohio), June 8, 1910, page 5.

In 1924,

sports columnist and sports historian, Frank Menke, similarly credited Kelly

with developing the “fade-away” slide:

Kelly was first to use the “fade-away” slide – and no man since

then, except Ty Cobb, has been able to duplicate it in its remarkable entirety.

. . . Before “King Kel’s” day, base

stealing was almost an unknown art.

Batters who could not hammer their way to second or third either were

advanced by another hitter – or died there.

Kelly would start his slide about ten feet from the bag with

a high leap into the air which shot his body downwards at the bag with

tremendous speed. . . .

Few basemen then had the nerve to try to block off

Kelly. He never went into the bag twice

the same way. He always threw himself

with cyclonic force and seeming more vicious.

Yet spiking by Kelly were rare happenings.

The Lincoln Star (Nebraska), July 11,

1924, page 14.

It is

therefore believable that “Slide, Kelly, Slide” could have been an homage to

his sliding acumen, but the lyrics, context and timing of the release of the

song suggest a different reason, or at least a double-meaning, as a knock

against Kelly for skipping out on Spaulding’s Australian baseball tour and

leaving Chicago for Boston.

Summary

An anonymous

janitor named “Uncle” Richard designed and built the first known playground

slide sometime between April 1902 and August 1903. Boston’s “sliding poles” and Coney Island’s

“Kelly’s Slide” (or “Helter Skelter”) show up in the historical record in May

1903.

But the

playground slide was not imagined from whole cloth. It was part of a continuum of gravity-powered

sliding entertainments including the good-old cellar door. Other predecessors include “Shooting the Chutes,”

“water toboggans,” “water slides,” “toboggans” and the roller coaster, each of

which has its own fascinating history – but that’s a story for another day.

|

| Evening Star (Washington DC), June 4, 1922. |

|

| Washington Post (Washington DC), July 2, 1905. |

[i] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 11, 1911,

page 22.

[ii] When

the automobile made streets even more dangerous a few years later, it became

necessary to develop traffic codes with new violations, like jaywalking, to

live in harmony with the new technology. See my earlier piece, Jaywalkers

and Jayhawkers - a Pedestrian History and Etymology of "Jaywalking."

[iv]

The report of “Uncle” Richard’s “shoot the chutes” slide disproves earlier

stories about the purported “first playground slide.” On April 17, 2012, the BBC and The Daily Mail published stories online with images purporting

to be the “World’s first children’s slide.”

The slide, they reported, was invented by a man named Charles Wicksteed,

who, they claimed, installed the first slide in Wicksteed Park in Kettering,

Northamtonshire in 1923. Paige Johnson

of Play-Scapes

playground blog quickly refuted the claim with images of slides at the

Russian Tsar’s summer palace (1910), Coney Island (1905) and a recent image of

a restored slide in Philadelphia believed to have been installed in 1904. The Play-Scapes post also included an image

of a slide on a rooftop in New York City dated to “circa” 1900, although the fashions

shown the photo almost certainly date that image to at least a decade or two

later.

[v] Blue Grass Blade (Lexington, Kentucky),

June 2, 1907, page 3.

[vi] The St. Louis Republic, April 17, 1901,

page 8.

[vii]

Mrs. Mark Stevens, Six Months at the

World’s Fair, Detroit, Michigan, Detroit Free Press Printing Co., 1895,

pages 210-211.

[viii]

Colliers , Volume 33, August 27,

1904, page 20 (“One of the things which the crowd likes best is a sort of

winding inclined trough, made of bamboo and polished smooth as glass.”).

[ix]

Benjamin Truman, History of the World’s

Fair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, H. W. Kelley, 1893, page 194.

[x]

Image from Cigarboxlables.com.

[xi] Dan de Vere’s Comic and Sentimental

Song-Book: Hudson’s Californian and North and South American Circus,

Quebec, “Le Canadien” Office, 1873, page 20.

[xii] Dan de Vere’s Comic and Sentimental

Song-Book: Hudson’s Californian and North and South American Circus,

Quebec, “Le Canadien” Office, 1873, page 20.

[xiii]

Wichita Eagle (Kansas), November 22,

1888, page 8.

[xiv]

Chase’s Franco joke resonated with audiences at the time, because rumors of the

strong-man dictator’s impending death were reported for several weeks before he

actually died. In a typical report by

the UPI, a headline read, “Brain test shows Franco is still alive” (Traverse

City Record-Eagle (Michigan), November 14, 1975, page 2). After his death, Chase parodied

such coverage with repeated reports that he was still dead.

[xv] He

performed at a benefit for newsboys on October 11, an Elks Club benefit on

October 28, and took a side-trip to Springfield, Missouri on October 31.

[xvi] The Sunday Leader (Wilkes-Barre,

Pennsylvania), May 27, 1888, page 6.