|

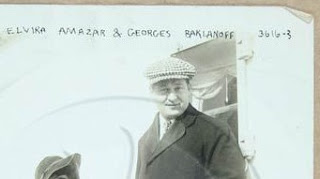

Indianapolis News, March 28, 1936, page 1.

|

It’s MARCH MADNESS!!! Time for a CINDERELLA team to go to the BIG

DANCE!!!

Time to winnow the field down to the

SWEET SIXTEEN!!! and the ELITE EIGHT!!!

In American pop-culture, all of these

expressions are widely associated with NCAA Division I championship basketball

tournament, where they were popularized by television basketball analysts like

Al McGuire, Brent Musburger and Dick Vitale during the late-1970s and early

1980s.

Most of these expressions, however,

are much older. “March Madness” and

“Sweet Sixteen,” for example, were firmly entrenched high school basketball idioms

in Indiana during the 1930s, “Cinderella” was commonplace by the 1940s, and

“Elite Eight” was standard in Illinois high school basketball during the 1950s.

“March Madness” and “Sweet Sixteen” both had long histories as non-basketball idioms before James Naismith wrote the rules of

basketball in 1891.

March Madness

Before Basketball

“March Madness” is older than the

NCAA men’s basketball tournament – and older than basketball itself. It was derived from the old expression, “as

mad as a March hare” which has “been around since at least the mid-1500s,”

originally as a reference to “the phenomenon of hares becoming very aggressive

during breeding season in March.”[i]

Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher,

playwright contemporaries of William Shakespeare whose fame rivaled the Bard’s

during his lifetime, used the adjectival precursor, “March mad,” several times

in the early 1600s.

The noun version, “March Madness,” appeared

in print as early as 1825, in a criticism of a rival newspaper’s positions on

tariffs and foreign affairs.

The Spring Fever.

“Mad as a March hare,” is an old adage, and applies with

great force to the condition of the Courant

about these days. As often as the year

comes round, and just about the time of the breaking up of the ice, the Courant

is seized with a strange nervousness on the subject of “Protection,” a sort of

sexual phrenzy which never shows itself at any other season.

This propensity to go crazy about the tariff, once in twelve

months, is a very proper matter for medical inquiry, and if looked into as it

deserves to be, might suggest some useful hints for the medical jurisprudence

of the country.

. . . To conquer Cuba is the mild dictate of common sense,

while to protect American Industry is ‘March’ madness!

By the late-1800s the expression was

regularly used to describe March weather.

-- Sunday night's severe snow storm, blustering, blow and wild wind was a let loose of old-fashioned March madness without method or merit. A friend suggested that it was next winter.

The Clarion Democrat (Clarion, Pennsylvania) March 20, 1869, page 3.

MARCH MADNESS

New York, March 28. -- New York experienced a somewhat topsy-turvy early morning to-day, due to a heavy wind, blinding snow and frozen sidewalks and streets. Cars collided with each other or with automobiles, signs and fences were blown down and trees uprooted, pedestrians were knocked over by trolley or motorcars or by mail trucks, one woman was blown into the East river, but was rescued, a frozen rail caused a short circuit which set fire to an elevated train and the rush hour traffic generally was hampered. A dozen persons were injured, several being removed to hospitals.

Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), March 28, 1919, page 1.

During the early decades of the

1900s, the expression was used in a several weather-related poems.

|

Des Moines Register, March 8, 1923, page 12.

|

|

Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1923, page 21.

|

|

Chicago Tribune,

March 26, 1929, page 12.

|

A third poem mixed its weather and

spring courtship metaphors.

March Madness.

By S. E. Kiser.

In the wild and windy month of March I met her.

I was merry, with the spirit of the Spring;

Her beauty made me wish that I could get her

To learn to look to me for everything. . . .

In the gusty month when winds become the maddest

I settled for the hearty lunch she ate;

Of all the people there, I was the gladdest;

How daintily she scooped things from her plate! . . .

In the month of March we took a ride together;

The taxi man drove wisely – to the park;

I told him that we didn’t mind the weather

And had no dread of riding after dark; . . .

It was in the month of March that, snuggling near me,

She told me of the husband that she had;

“Come out,” she said, “and help to make him fear me;

He has walloped both my brother and my dad!

Come out and give him chase,

And I’ll promise you his place;

You shall wed me when his hateful claim expires –

There was mist upon her hair

When I paid the taxi fare-

I am not at home, if any one inquires.

Pittsburgh Press, March 17, 1921, page

12.

In 1921, Babe Ruth broke Roger

Conner’s career homerun record while setting a new single-season record with 59

homeruns, setting off fan frenzy in spring training the following season. One baseball scribe dubbed the intense

interest in the Babe’s meaningless, pre-season homeruns a form of madness –

“March Madness.”

MARCH MADNESS.

The rooters raise a mighty shout

And make the

well-known welkin ring

When Ruth achieves a four-base clout,

Although it doesn’t

mean a thing.

Spring training may have been

interesting for Yankees’ fans in 1922, but it was generally (then as now) a

relatively hum-drum affair. High-school

basketball, on the other hand, provided excitement on an annual basis.

In Indiana in particular, the high

school basketball tournament became a form of madness – “basketball madness.”

|

Lansing State Journal (Lansing, Michigan), March 21, 1925, page 17.

|

“THE DAY” HAS ARRIVED.

The night before Christmas may intrigue a number of little

folk and those who minister to their desires.

For those who have ceased to believe in Santa Claus, however, it

scarcely can compete with the all-important date which marks the opening of the

annual state high school basketball tournament.

To say that the fans are agog would be putting it

mildly. All the enthusiasm which has

been accumulating during the last twelve months scarcely diminished by the

occasional effervescence of the playing season, is not ready to burst forth in

a frenzy of basketball madness.

The Indianapolis Star, March 1, 1929, page 8.

Coming as it did in March every year,

“March Madness” was a natural fit. The

expression was first used no later than 1931.[ii] The earliest known example played off the

conventional March madness-as-weather usage.

March Madness

The elimination of Anderson Tech, Columbus and Shelbyville

were only mere flurries of what is to follow this week at the various

basketball conventions in sixteen regional cities. – Newcastle Courier-Times.

Rushville Republican (Rushville, Indiana), March 11, 1931, page 2

This early use may have been a

one-off. The next-earliest example of

“March Madness” in reference to a basketball tournament appeared in 1937. In any case, it was certainly not yet

standard in 1931. A report of the

Indiana state finals that same year used “basketball madness,” not “March

Madness.”

Butler Fieldhouse, Indianapolis, March 21. – Indiana’s basketball madness reached its peak here

to-night as Muncie’s Bear Cats and Greencastle’s Cubs tore into each other for

the state high school championship. They

were the survivors of a total of 766 quintets whch three weeks aago began play

for the title.

The South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana), March 22, 1931, page 8.

“Basketball madness,” and not “March

Madness,” appeared regularly, if infrequently, through 1936.

[A]ll eyes were on the Jefferson-West Side encounter this

afternoon. “Basketball madness” at its

best!

Journal and Courier (Lafayette, Indiana), March 2, 1935, page 9.

|

Muncie Evening Press (Muncie, Indiana), March 18, 1935, page 4.

|

In 1936, on the occasion of the 25th

anniversary of the Indiana State High Basketball Tournament, an Associated Press item appearing in

several newspapers used the expression, “basketball madness.”

Crawfordsville, Ind., Feb. 19. J- Indiana, now in the throes

of its annual basketball madness will stop

cheering the 1936 teams long enough on Feb. 22 to honor the nine men who, as

members of the Crawforsville High school team, won the first state

interscholastic tournament back in 1911.

South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana), February 19, 1936, Section 3, page 2.

In 1937, an Associated Press appearing in several newspapers used the

expression, “March Madness.”

|

Journal and Courier (Lafayette, Indiana), January 5, 1937, page 13.

|

But the expression may have been in

regular use before 1937, even outside of Indiana, as suggested by its use in

the neighboring state of Michigan that same year:

High school basketball tournament time, oft referred to as March Madness, is with us in full

force.

The Escanaba Daily Press (Escanaba, Michigan), March 7, 1937, page 36.

Within a few years, “March Madness” would

be in regular and frequent use throughout the Midwest, including in Illinois

(1940), Iowa (1941), Ohio (1944) and Wisconsin (1947).

Other states also had basketball

tournaments, but without the attendant “madness.” In Nevada, for example, one newspaper used

“March Madness,” without any hint of irony or humor, to describe tax season on

the same page as it reported the results of a local conference basketball

tournament:

|

Nevada State Journal (Reno, Nevada), March 1, 1939, page 1.

|

But not all basketball tournaments

were equally “mad.” A distinguishing

element of what made Midwestern “March Madness” particularly crazy was the fact

that every team in the state took part in the tournament, providing a longer

tournament season, more games, more hope, more risk, and paving the way for

more crazy, maddening upsets.

In 1945, a region of New York adopted

a similar format. An article announcing

the new format explained the difference between a conventional tournament and

what was then understood as “March Madness.”

Called ‘March

Madness’

Preliminary plans for tournament play are well under way, it

was said today by Kurt Beyer of Norwich, sectional chairman.

Tournament basketball, under the sponsorship of the state

association, will be the feature athletic attraction of the month of March. Known in the Midwest as “March Madness, the

sport will be available for each of the 85 schools in Section-Four.

The tournament plan for the section is comparable to that

employed in the Midwestern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and others where

all schools are permitted to enter the play for championships. Contrasted to this is the plan prevalent in

other sections of this state where only league winners meet in eliminations for

championships in various classes of schools.

Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), February 1, 1945, page 15.

Even though every team in Indiana

could participate in the early rounds of the state high school basketball

tournament, only a select few were invited to Indianapolis for the last few

rounds; sixteen teams – the “Sweet Sixteen.”

Sweet Sixteen

Like “March Madness,” “Sweet Sixteen”

had a long history as an unrelated idiom before it was picked up in basketball. And even then, the earliest examples of it in

basketball referred to pre-season or pre-tournament rankings, and not the final

sixteen teams remaining in a tournament.

Before

Basketball

|

Los Angeles Sunday Herald, April 3, 1910, Section 4, page 4.

|

Then, as now, “Sweet Sixteen” was

used to describe young girls in the flower of youth as they bloomed into

adulthood. The expression is found in the poem, Wyoming, by an American poet

named Fitz-Greene Halleck, said to have been written in 1821.

WYOMING

Thou com’st, in beauty, on my gaze at last,

“On Susquehannah’s side fair Wyoming!”

Image of many a dream in hours long past,

When life was in its bud and blossoming,

And waters gushing from the fountain spring . . .

. . .

There’s one in the

next field – of sweet sixteen, –

Singing, and summoning thoughts of beauty born

In heaven, with her jacket of light green,

“Love-darting eyes, and tresses like the morn,” . . .

June, 1821.

F. G. H.

New York Evening Post, February 10, 1827, page 2.

Another American poet, William B.

Tappan, used the expression in 1822.

To a Lady of Sixteen

By W. B. Tappan.

Lady! While gaily opes on you

The world’s alluring, witching smile;

While flowers of every form and hue

Spring forth, your pathway to beguile –

O Lady, in the bursting dawn

Of hope, may real bliss be seen,

May bland contentment gild your morn,

And peace be yours at fond SIXTEEN.

. . .

Though cloudless suns for thee may rise,

And bright the joys that for thee shine;

O who may tell these beauteous skies,

These cloudless suns shall long be thine;

Yet long may these your day illume,

And may not storms, with rigor keen,

Assail the flower that loves to bloom

On the fair cheek of sweet SIXTEEN.

American Repertory and Advertiser (Burlington, Vermont), September 3, 1822, page 4.

“Sweet Sixteen” was used as a

trademark for beauty products as early as 1884.[iii]

A “sweet sixteen birthday party” or

“sweet sixteen party” was a “thing” by the 1880s.

Miss Blanche Loriomr gave a “sweet sixteen” birthday party on

Saturday evening to a number of the “sweet sixteens”

of the town.

Jackson County Banner (Brownstown, Indiana), February 11, 1886, page 1.

“Sweet Sixteen and never been kissed”

appeared several decades later.

Sweet sixteen and never been kissed. Inquire of W. Duland for free

samples.

The Marion Star

(Marion, Ohio), December 21, 1892, page 5.

“Of course I went, I was a little country girl, ‘Sweet-sixteen-and-never-been-kissed’ kind of one you

know.”

Juniata Sentinel and Republican (Mifflintown, Pennsylvania), April 12, 1893, page 4.

In the early 1900s,there were several

“Sweet Sixteen” songs and stage acts.

|

The Austin American (Texas), November 30, 1919, Section C, page 3.

|

In 1917, the White automobile company

sold a car with a four-cylinder, sixteen-valve engine as, “The Sweet Sixteen.”

|

Los Angeles Times, July 1, 1917, Part 6, page 4.

|

In a report of an automobile race in

Los Angeles in 1923, “Sweet Sixteen” took on a meaning more closely related to

the later basketball usage.

With every one of the sixteen racing

cars entered for next Sunday’s big championship motor event at the Los

Angeles Speedway so fast that speed qualification elimination tests have been

abandoned as needless, there will be no “scratches” of entrants.

This announcement . . . was made after it became known that

not a car of the “sweet sixteen” has done less

than 107 to 108 miles per hour in last week’s informal practice laps.

Los Angeles Times, February 19, 1923, Sports News, page 1.

“Sweet Sixteen” was still in regular

use in its conventional sense as well.

|

The Post-Star

(Glens Falls, New York), March 25, 1926, page 6.

|

|

Minneapolis Star, July 14, 1926, page 1.

|

Basketball

The earliest examples of “Sweet

Sixteen,” as applied to high school basketball tournaments in Indiana, did not

refer to the sixteen teams playing in the final rounds of a tournament, as is

generally the case today. Instead, they

referred to pre-season or pre-tournament predictions of the best teams in the

county or state, or the teams expected to make it to the final weekend of the

tournament in Indianapolis.

In 1927, a sports columnist in

Muncie, Indiana invited readers to send in their lists of the best teams in their

respective counties. Three readers

submitted lists with varying numbers of teams, each one cribbing the name of

their list from some other source.

Dan from Muncie, for example, submitted

his “Big Ten” in the state, likely a reference to the collegiate athletic

conference known by that name since the 1917 season. Bob from Yorktown submitted his “Natural

Eleven” of Delaware County, a nod to the game of Craps. And finally, Bolivar and Jushua of Randolph

County submitted their “Sweet Sixteen” of that county.

|

Star Press

(Muncie, Indiana), March 3, 1927, page 10.

|

A few weeks later, an Associated

Press article used the same expression to refer to the sixteen teams playing

for the championship in Indianapolis.

INDIANAPOLIS, March 18. – Sixteen high school basketball

teams entered the exposition building at the state fair grounds today, each

quintet hopeful of wearing home tomorrow night the crown emblematic of the

Indiana interscholastic championship.

The sweet sixteen were survivors of the starting field of 731 that

dwindled to sixty-four two weeks ago in the sectional tournaments and shrunk to

16 in the regionals last week.

Journal and Courier (Lafayette, Indiana), March 18, 1927, page 1.

By 1928, the new expression was

idiomatic.

“Sweet sixteen” also applies to the contestants in the high school

basketball finals.

The Indianapolis Star, March 14, 1928; The Star Press

(Muncie, Indiana), March 16, 1928, page 6.

INDIANAPOLIS, March 9 – (AP) – A few more hours and well will

know who will be the Sweet Sixteen.

Palladium-Item (Richmond,

Indiana), March 9, 1929, page 11.

|

Journal and Courier (Lafayette, Indiana), March 20, 1931, page 12.

|

BACK HOME AFTER SEEING THE “SWEET SIXTEEN.”

The Indianapolis News, March 14, 1935, page 18.

By 1935, Illinois joined Indiana in

hosting a “Sweet Sixteen” in its state capital to wind up the state high school

basketball championship tournament.

Champaign. March 20. – (AP) – The “Sweet

Sixteen” of Illinois high school basketball, last of a field of 860,

will pair off here tomorrow for the opening round of the state tournament.

The Dispatch

(Moline, Illinois), March 20, 1935, page 18.

It was in Illinois, a decade later,

that “Elite Eight” would become idiomatic in basketball tournament lingo.

Elite Eight

As was the case with “March Madness”

and “Sweet Sixteen,” there were a few, random examples of its use in basketball

and other sports became a common basketball tournament idiom. William Mullins posted several early examples

of “Elite Eight” on an online discussion board hosted by the American Dialect

Society, each of which appear to be one-off, literal, pre-idiomatic uses of the

expression.

"A week ago the qualifying round of this competition was

played and the elite eight to emerge into the

match play tourney were: R. M. Eyre,

David Duncan, Wilberforce Williams, Leslie Comyn, D. Hardy, A. S. Lilley, R. J.

Davis and Dr. Tufts." [golf tournament]

San Francisco Chronicle, August 7, 1913, page 9.

"Home clubs that go into the race rather hopelessly are

going to be surprised to find themselves among the

elite eight. Eight teams are to

continue in match play after the qualifying round." [golf tournament]

Cleveland Plain Dealer (Ohio), May 26, 1926, page 23.

"Ottumwa's record is slightly better, the

"mystery" five having scored an average of 30 points per game in

tourney competition while holding its opponents to a bare 14 tallies, the

lowest of any of the elite eight." [Iowa

state basketball tournament]

Daily Nonpareil (Council Bluffs, Iowa), March 15, 1928, page 8.

On at least one occasion, the

survivors of the first round of the “Sweet Sixteen” in Indiana were referred to

as the “elite eight,”[iv]

but it does not appear to have been idiomatic, as I could not find any other

examples in print during the period.

“Elite Eight” first appears regularly in Ohio

during the early 1950s. But in Ohio,

which had abandoned the traditional “March Madness” format for a two-class

system with big schools and smaller schools competing in separate tournaments,

the “Elite Eight” of 1951 were the eight teams, four from Class A and four from

Class B, competing in the semi-finals – not the final eight teams in a

single tournament.

When “Elite Eight” came into its own

in Illinois in the mid-1950s, it wasn’t without controversy. In 1954, the state of Illinois floated the

idea of reducing the number of teams it invited to Champaign for the last few

rounds of the championship tournament.

AN UNFOUNDED RUMOR has the “Sweet 16” doomed for a couple of

years at least. . . . If the tourney

goes to eight teams (and it will) . . . it will be referred to as the “Elite Eight.” . . . A four-team affair would be

called . . . “Fortunate Four.”

Galesburg Register-Mail (Galesburg, Illinois), April 30, 1954, page 21.

Two years later, the prediction came

to pass – at least as to the number of teams in the tournament, if not the

name. Like the Big 10, which clings to its

well-known, numerical trademark despite a fluid number of members, the

powers-that-be of the Illinois basketball bureaucracy fought logic and human

nature to hang on to the tried-and-true “Sweet Sixteen,” even in the face of

overwhelming resistance. “Elite Eight”

would win the day, but there were plenty of alternatives.

SPRINGFIELD – UP – The Illinois High School Assn., meeting

Wednesday to arrange its new eight-team basketball tournament finals, said the

meet will still be called the “Sweet Sixteen.”

. . . It was pointed out sports writers and announcers are already

talking of the “Elite Eight,” and the “V for victory Eight,” and the IHSA had

better name the tournament while it had a chance.

“It’s still the ‘Sweet Sixteen’”, an IHSA member insisted.

. . . They have opened the floodgates to what may develop into

one of the biggest name-calling contests ever to hit the state’s sports pages.

They have declared open season on the “______ Eight.”

When thousands of fans are setting battered and dazed in the

wake of adjectives flowing from the typewriters and lips of sports writers,

then perhaps they will strive to bring order.

It will be too late.

So if this tournament is to be named, for the coeds, we

suggest “Embraceable, Endearing or Enchanting Eight.”

Coaches may like the “Enormous Eight,” educators the “Enlightened

Eight” or “Educated Eight,” winners the “Invincible Eight,” losers the “Erratic

Eight” or “Exasperating Eight.”

Fans my like the “Expert,” “Evasive” or “Errorless Eight.”

In the locker rooms on victory night they will be the “Elated

Eight,” while to other schoos they may be the “Envied Eight.”

And to those who wanted the “Sweet Sixteen” forever, they now

can look forward only to the “Endless or perhaps Eternal eight.”

The Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, Illinois), November 17, 1955, page 20.

Thankfully, in the end, logic

prevailed.

Alton Evening Telegraph (Alton, Illinois), March 17, 1956, page 13.

Cinderella

The proverbial “Cinderella” team has

been a regular feature of basketball reportage since at least 1936. The name might easily have been simply

borrowed from the well-known fairytale, but given the timing of several early

examples, it seems likely that the new use of the word was as much, if not

more, by the nickname of boxer James J. Braddock, the “Cinderella man,” who

rose from obscurity to win the heavyweight title from Max Baer in 1935

(Braddock would lose the title to Joe Louis in 1937).

|

Chillicothe Gazette, March 23, 1936, page 9.

|

|

Carroll Daily Herald (Carroll, Iowa), December 31, 1937, page 4.

|

“Cinderellas” were a dime-a-dozen in

high school basketball tournaments by the early 1940s. But the two earliest examples “Cinderella”

teams in a high-profile, major college basketball tournaments I found are both

from 1944, when the “Cinderella Team” from St. John’s University, champions of

the National Invitational Tournament (N. I. T.), squared off against the “Cinderella Kids”

from the University of Utah, champions of the NCAA national championship

tournament, for the “Mythical” national championship, at a time when the N. I. T. and NCAA tournaments had equal stature.

|

Rapid City Journal (Rapid City, South Dakota), March 27, 1944, page 6.

|

|

Daily Herald

(Provo, Utah), March 29, 1944, page 4.

|

|

Daily Sentinel

(Grand Junction, Colorado), March 31, 1944, page 10.

|

Big Dance

The title character in the classic

fairytale Cinderella was famously invited to a royal ball. And since a royal ball is nothing more than a

big dance, “Big Dance” was a natural fit to describe “March Madness,” with its

endless possibilities of “Cinderellas” sneaking into the “Sweet Sixteen” or “Elite

Eight.” It may have been a natural fit,

but it was apparently not immediately obvious.

The earliest example I could find is from 1976, and it did not become a

popular expression until the 1980 NCAA basketball tournament.

One writer in Illinois, however,

nearly connected the dots in 1951.

This week Cinderella will continue polishing the woodwork,

taking time out only for non-league dances with

Chicago Teachers and Carroll College.

She plans to do a quick Charleston with

Chicago tonight on the Teachers’ own dance floor

in the Windy City, and has invited Carroll to DeKalb for a cake walk next Saturday.

The Daily Chronicle, February 20, 1951, page 14.

In 1976, Depaul University’s athletic

director, Gene Sullivan, likened his team to Cinderella and the NCAA tournament

to a ball.

“We’re the last ones invited to the ball, but, like Cinderella,

we hope to have a good time,” said Sullivan.

“Meyer should be coach of the year.

We lost three regulars from last year and took on a suicide

schedule.

Chicago Tribune,

March 8, 1976, Section 4, page 1.

A few weeks later, a newspaper in

Tampa, Florida, referred to the Florida state high school basketball tournament

as a “big dance” in a piece bemoaning the drop-off in talent following the graduation

of several recent stars of the tournament, including future NBA superstars

Darryl Dawkins, Otis Birdsong, and Michael Thompson.

Perhaps it was befitting that the 1976 tournament was not

such a great one. It might have been fitting

that the attendance was poor.

For indeed, it was good old Jacksonville’s last year for the

big dance.

It was coming to an end.

The tournament will move to Lakeland’s Civic Center for at

least the next three years.

The Tampa Tribune, March 16, 1976, page 2 C.

By 1980, and increasingly afterward,

the “Big Dance” became a common euphemism for the Final Four of the NCAA

Division I National Basketball Tournament.

If Billy Tubbs is

thinkin’ about dustin’ off his dancin’ shoes, he’s gonna have to hot-foot it

past Clemson tonight.

“We sure would like to go to the prom,” Tubbs, Lamar

University’s coach, says. That, of

course, is the Final Four, the next-to-last step to the

NCAA basketball championship.

Times-Tribune

(Scranton, Pennsylvania), March 13 1980 page 32.

For a good time, Al Wood likes to lace up his dancin’ shoes

and head for the nearest disco. He’s no

two-left-footed stumblebum off the streets, either. His teammates on last year’s touring Olympics

team report that the silky senior forward on North Carolina could git down,

boogie and shake his booty with the best of them.

Wood wore sneakers to The Big Dance,

a popular euphemism for the NCAA Final four . . . .

Tampa Bay Times

(St. Petersburg, Florida), March 29, 1981, page 11C.

Today, grade-inflation being what it

is, the “Big Dance” frequently refers to the entire tournament.

Darryl Dawkins, Otis Birdsong and

Michael Thompson all playing in the same high school tournament???

That was a Big Dance.

[iii] Official Gazette of the United States Patent

Office, August 15, 1916, page 931 (Sweet Sixteen trademark, alleging use

since 1884 on “face or complexion powders.”

[iv] Journal and Courier (Lafayette,

Indiana), December 29, 1938, page 16 (“Lebanon once lost something like 16

games during the regular schedule, yet won its way to the elite eight in the

state finals . . . .”).