“Jigaboo” is a variant of “Ji-ji-boo,” the first name of a character in a song about an Irishman who became the king of an “Indian isle.” The song, “I’ve Got Rings on My Fingers, or Mumbo Jumbo Jijjiboo J. O’Shea,” made its debut in the play, “The Midnight Sons” (1909), produced by Lew Fields, part of the comic duo, Weber & Fields.

The lyrics tell of an Irishman named Jim O’Shea, who “was cast away upon an Indian isle.” The “natives there they lik’d his hair, they lik’d his Irish smile, so made him chief Panjandrum, the nabob of them all,” after which, “they call’d him Ji-ji-boo Jhai.” Although he keeps a harem, with “wives galore,” he misses his Irish wife, and writes for her to join him, as his “Mistress Mumbo Jumbo Jij-ji-boo J. O’Shea.”

Now Jim O’Shea was cast away

Upon an Indian Isle

The natives there they liked his hair

They liked his Irish smile

So made him chief Panjandrum

The Nabob of them all

They called him Ji-ji-boo Jhai . . .

Follow this link to listen to hear Billy Murray sing the song.

Scott, Maurice, Billy Murray, Fred J Barnes, and R. P Weston. I've Got Rings on My Fingers. 1910. Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-129033/ .

In popular usage, however, “Ji-ji-boo” quickly morphed into “Jigaboo” or “Zigaboo,” and the meaning shifted from the name of the Irish character in the song to the name of the fictional island and its native, darker-skinned inhabitants. The words later came to refer to black people, specifically, likely based on the characterizations of the island natives on the stage, presumably portrayed by white actors in blackface, mixing their African, East Indian and South Pacific metaphors.

The early shift from “Ji-ji-boo” to “Jigaboo” and “Zigaboo” may have been influenced by familiar, unrelated, pre-existing words, “Zigaboo” (the name of a fraternal organization) and “Gigaboo,” a character in an early work by L. Frank Baum, who later wrote “The Wizard of Oz.”i Based on the context in which it was used, Baum’s “Gigaboo” may have been a blend of “giant” and “bugaboo” - a large, scary monster. The similar “bigaboo” was an occasional variant of “bugaboo.”

A few early examples of “Zigaboo” or “Jigaboo” were synonymous with “Bugaboo” or “Boogie Man,” consistent with the meaning of the pre-existing words, “Bigaboo” (alternate spelling of “Bugaboo”) and Baum’s “Gigaboo.” But most of the early examples used the words to refer to Pacific or South Seas islanders or to the name of imaginary islands or remote, exotic countries, consistent with the plot of the song about “Ji-ji-boo O’Shea.”

“Zigaboo” referred to a black person by at least 1918 (perhaps as early as 1914), and “Jigaboo” by 1921. During the 1920s, a troupe of black entertainers used “Zigaboo” in the title of one of their most popular skits, “Zigaboo Land,” and a black duo used “Jigaboo” as the title of their act. Writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance used both words neutrally, with no apparent negative connotation, in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. The two words and their short forms, “Jig” and “Zig,” were not described in print as pejorative until the 1940s.

Just as the evolution of the word from “Ji-ji-boo” to “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo,” the plot of the song was influenced by a long line of predecessor songs and plays about white men washed up on remote islands finding themselves in leadership roles, by proclamation or by marriage.

Earlier Influences

The story of a Westerner stranded on a South Seas island getting himself into a leadership role was not new - it dates at least to May 31, 1830, and the song “All in the Tonga Islands.” The decision to stage a revival of the plot element in 1901 may also have been influenced by actual events. Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea (the character, if not the name) bears more than a passing resemblance to the life and career of Daniel O’Keefe, an Irish-born American who was stranded on the island of Yap in the Caroline islands in the 1870s, and who later established a successful trading business, dealing primarily in the coconut byproduct, copra, which was in demand at the time for use as lamp oil.

Numerous items in newspapers and periodicals throughout the 1890s and early 1900s related sketchy details of Daniel O’Keefe’s colorful life. He sailed from Savannah, Georgia on a merchant vessel in the 1870s, leaving his wife behind, and for years was presumed lost at sea. He popped back up again more than a decade later, as a copra mogul on Yap. Early accounts of his life reported that he “lived like a prince,” which may have been true. Later, more fanciful accounts of his life, referred to him as “King O’Keefe,” embellishing the story with rumors that he had married an island king’s daughter, and later became “King” himself.

|

| "King O'Keefe," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 29, 1903, page 6. |

Stories about O’Keefe’s life may have inspired more than one song about an Irishman ruling a remote island. Weber & Fields 1901 production, “Hoity Toity,” featured the song, “King Kazoo of Kakaroo,” about an “Irish cannibal king,” who became the king of a “cannibal island” when given the choice of “mountin’ the throne or being an Irish stew.” One of his first acts as King is to “change their bill of fare,” making them vegetarians instead.

|

| King Kazoo |

Eight years later, “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” would also be the King of a remote, exotic island, in shows produced Lew Fields of Weber & Fields. Maud L’Ambert sang “I’ve Got Rings on My Fingers and Bells on My Toes, or Mumbo Jumbo Jijjiboo J. O’Shea” in his production of “The Midnight Sons,” and Blanche Ring sang it in “Yankee Girls,” also a Fields production. The song and the character’s name would become the apparent origin of the words, “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo.”

|

Scott, Maurice, Weston, and Barnes. I've Got Rings on My Fingers. Francis, Day & Hunter, New York, 1909. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.100007971/ . |

|

Scott, Maurice, Weston, and Barnes. I've Got Rings on My Fingers. T. B. Harms & Francis, Day & Hunter, New York, 1909. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.100007972/ . |

The potential early influences do not end there. A song entitled, “All in the Tongo Islands” (or simply, “The Tongo Islands”), appeared in several song books from the 1830s through the 1850s. The song has similarities to both “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” and “King Kazoo of Kakaroo,” suggesting Weber & Fields may have been familiar with it. “The Tongo Islands” also has similarities to an earlier song, “King of the Cannibal Islands,” suggesting that it may have been influenced by it.

“King Kazoo” is about a stranded Irishman who is crowned “King Kazoo of Kakaroo,” a title with a lot of K’s. “The Tongo Islands,” is about a shipwrecked American who marries the king’s daughter, becomes a chief, and takes the name “Koora Kira Kee,” a name with a lot of K’s. “I’ve Got Rings on My Fingers” is about a stranded Irish-American who is made “chief Panjundrum” of an “Indian isle,” and takes the name “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea,” a name with a lot of J’s.

|

The Popular National Songster, and Lucy Neal and Dan Tucker’s Delight, Philadelphia, John B. Perry, 1845, page 89. |

In “The Tongo Islands,” the stranded Westerner’s native bride wears “a feather through her nose, and rings . . . upon her toes.” In “I’ve Got Rings on My Fingers,” the stranded Irish-American wears “rings on my fingers and bells on my toes.”

“The Tongo Islands” also has thematic and lyrical elements that link it back to “The King of the Cannibal Islands.” In “Tongo,” the stranded Westerner runs away when threatened by the local cannibals. In addition, the refrain to “The Tongo Islands” includes the words “hoki poki” (in some versions, “Hokey Pokey”), as does “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” which was the original “Hokey Pokey” song.

Hokee pokee wonkee fum,

Puttee po pee kaihula cum,

Tongaree, wongaree, ching ring wum,

The King of the Cannibal Islands.

“The King of the Cannibal Islands,” An Original Comic Song, by A. W. Humphreys. Air - Vulcan’s Cave.ii The Apollo, Volume 2, London, H. Arliss, 1830, page 22.

Swango, Tongo, hoki poki, hingri ching-

ri, soki moki,

Swango, Tongo, hooki pooki,

All in the Tongo islands.

“The Tongo Islands,” The New Song Book, Hartford, Ezra Strong, 1836, page 18.

[For more information on the history of “Hokey Pokey” and “The King of the Cannibal Islands,” see my post: "'Hokey Pokey' and Madame Boki - Hawaiian Royalty and the History and Origin of 'Hokey Pokey'".]

|

Music Division, The New York Public Library. "King Kazoo of Kakaroo" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1901. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/92940d27-7acb-ea31-e040-e00a1806777e. |

Unlike Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea, the stranded Western sailor in Hoity Toity is not expressly an Irishman, but he does accept his appointment to the role of “ragtime Cannibal King” in order to avoid becoming an “Irish stew.” There is no marriage in “King Kazoo,” as there had been in “The Tongo Islands” and there would be in “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea,” but he is made a “Cannibal King,” similar to both “The King of the Cannibal Islands” and “The Tongo Islands.”

Just as the plot elements of “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” may have been influenced by previous songs and shows, the words “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo” may have been influenced by pre-existing words with unrelated meanings.

Gigaboo/Zigaboo/Bigaboo

While the historical through-line from “Hokey Pokey,” the “King of the Cannibal Islands,” to “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea,” the “nabob” and “chief Panjundrum” of an “Indian Isle” are interesting, they do not explain how or why “Ji-ji-boo” became “jigaboo,” or how or why the name of an Irish character on an East Indian island came to refer to African-Americans.

The name, “Ji-ji-boo,” as written in the lyrics to the 1909 song, appears to have been supplanted in popular usage by pre-existing words that sound similar but which have unrelated meanings.

“Igiboo” appeared in print at least once, in 1893, as a nonsense words used used to harass the batter in a game between the Philadelphia Phillies and the Boston Beaneaters. In the third inning, with Boston at bat, the umpire ordered Boston first baseman Tommy Tucker to head back to the bench from the third-base coaching box, for improper base-coaching.

The most pleasing feature of the game occurred in the fourth inning when the irrepressible, loudmouthed, cantankerous Tom Tucker was ordered to the players’ bench. . . . Tommy was coaching from the third base side.

Tommy didn’t stay in the box. He got close up to the line and kept up his cry of “Ugh, oh, ugh, igiboo, hi, ho, hoo, ugh,” until the noise became almost unbearable.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 17, 1893, page 3.

“Zigaboo” appeared in print at least twice, in 1896 and 1905, as the name of social organizations, one in Nebraska and one in either Kansas or Ohio, it’s not clear.iii

Several members of the “Zigaboo” society and their ladies were in Lincoln last evening and attended the rendition of “Wang” at the Funke.

The Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), January 31, 1896, page 8.

Oberlin (Ohio) Tribune: Miss Ida Cole and Miss Nina Torey entertained the “Zigaboos” with a picnic party at Birmingham, last Saturday afternoon.”

Ellis County News Republican (Hays, Kansas), August 19, 1905, page 7.

More notably, perhaps, “Gigaboo” appeared in print as early as 1900 in a book by L. Frank Baum, who is best known for writing The Wizard of Oz. It appeared in book that was published twice, under two different titles.

“Gigaboo” first appeared in A New Wonderland, published in 1900, the same year in which The Wizard of Oz was released.

“A New Wonderland” is the title, and the author, Frank Baum, has made a successful, original venture in the realm of Fairyland, the wonders of his stories being presented in a vein of irresistible drollery. . . . the Gigaboo which lived in a cavern of rock candy and ate from trees of which the fruits were cranberry tarts.”

Buffalo Courier, November 4, 1900, page 11.

The boys will also delight in the perpetual warfare between the good king and the mischievous Purple Dragon, the conquest by Prince Jollikin of a curious creature called a gigaboo, and the wonderful adventure of Prince Fiddlecumdoo with the giant hartilaf.

“A New Wonderland,” Book Notes, A Monthly Literary Magazine and Review of New Books, New York, Siegel-Cooper, Volume 6, Number 3, March 1901, page 282.

In 1903, A New Wonderland was reissued as The Magical Monarch of Mo, with some new material, and the scene of the action changed from “Phunnyland” to “the beautiful Valley of Mo.”

The character of the “Gigaboo” was a giant monster who lives in a cave and scares people, like a “bugaboo” or its occasional variant, “bigaboo.”

In one of the great hollows formed by the rock candy lived a monstrous Gigaboo, completely shut in by the walls of its cavern. It had been growing and growing for so many years that it had attained an enormous size.

L. Frank Baum, The Surprising Adventures of the Magical Monarch of Mo and His People, New York, Dover Publications, Inc., 1968, unabridged republication of the text and line drawings of the work as published by The Bobbs-Merrill Company in 1903, page 110.

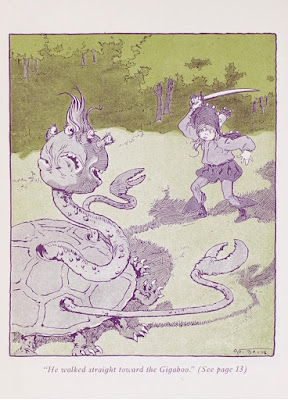

|

| “He walked straight toward the Gigaboo.” |

|

The Magical Monarch of Mo, Dover, 1968 (Bobbs-Merrill, 1903). |

The book does not provide any guidance on how to pronounce “Gigaboo,” but its gigantic proportions and frightening appearance and behavior (similar to that of a “bugaboo”), suggests it may be a portmanteau of gigantic and bugaboo. If so, it the intended pronunciation may be a soft <g>, like a <j> sound, and may have been pronounced exactly like “jigaboo.” At least one newspaper, for example, expressly referred to “Ji-ji-boo J.” as “Gig-a-boo Jay.”

I would not be much surprised to see Gig-a-boo Jay coming home some of these days with a thousand dollar machine as he gets his tootsy-wootsy most every thing she wants and he says the best is none to good for her.

Jamestown Weekly Alert (Jamestown, South Dakota), August 25, 1910, page 8.

In addition, in keeping with the “Bugaboo” theme, the rhyming, alternate spelling, “Bigaboo,” appeared in print occasionally for at least a decade prior to 1909.

In Kansas in 1897, Populist Governor John W. Leedy warned against the unfair criticism of the Populists (“pops”) by “Grub Street scribblers” (Eastern and Big City journalists).iv

“Grub Street” is the new big-a-boo of the pops according to the gospel of Gov. Leedy.

Council Grove Republican (Council Grove, Kansas), January 22, 1897, page 4.

In 1907, an article about eliminating the last roadblock to construction of a railroad cut-off, referred to the problem overcome as a “big-a-boo.”

The Santa Fe Cut-Off Located

All doubt as to where the Santa Fe will locate their new route through here is set at rest. Last week, Mr. Eby, the right-of-way man purchased right way over the last survey made of all those who he could make terms with and forever puts at rest the big-a-boo that has stood in the way of Quinlan’s advancement.

The Quinlan Mirror (Quinlan, Oklahoma), October 24, 1907, page 1.

The use of “Jigaboo man” to mean precisely the same as a “Bugaboo man” supports the notion of a connection between “bugaboo”/“bigaboo” and “jigaboo”/“zigaboo.” During the time period between the introduction of the song “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” and before “Jigaboo” took on its now familiar meaning, the expression “Jigiboo man” was used on occasion in the sense of a “Bugaboo man.” In 1910, for example, an article about scare tactics used in university fund-raising noted, “they try to scare us with the ‘Jigaboo Man’ into a fit and when we ‘come out of it’ we wonder how it all happened.”v

In 1911, a song called “The Jigaboo Man” was said to be an imitation of an earlier song, the “Yama Yama Man,” which, in the context of the song, had the same meaning as a “Bugaboo” or “Boogie Man.”

The “Yama Yama Man” of the song was essentially a bugaboo or boogie man who scared children in their bedroom. The name, “Yama Yama,” was coined to replace the word “pajama,” when two plays booked to the same theater were slated to have pajama songs.

When “Three Twins” was in Chicago every one wondered what a Yama Yama Man was, but, of course, we were all too polite to inquire. The truth has at last leaked out; he is a first cousin to a “pajama man.” . . .

When “Three Twins” was rehearsing in Chicago Karl Hoschna, the composer, was asked to furnish a “pajama man” song. He wrote one, only to learn that it could not be used in the production owing to the fact that the next play booked at the Whitney opera-house had as its main feature a pajama number. . . .

That afternoon, as he and Collin Davis, who wrote the lyric of “Yama Yama Man,” and Hoschna sat together, wondering what they would call the song, Sohlke kept repeating “Pajama-jama-yama-yama.” Suddenly he brightened up and cried:

“Did either of you fellows ever hear of a ‘Yama Yama Man’?”

The Chicago Inter-Ocean, July 26, 1908, Magazine, page 9.

Just what Miss Bessie McCoy is supposed to be is difficult to make out until she discards a weird make up that makes her look like a dippy Ophelia and bulges out in a Pierrot costume to sing “The Yama Yama Man.” Then she is a “hit.” She dances around ten Yama Yamas who look as though they had been banished from a picture book for scaring pink little girls and purple cows, and gives up parts of her song to droll imitations of our to-be-or-not-to-be-Hamlet, Mr. E. Fitzgerald Foy.

The New York Evening World, June 17, 1908, page 15.

She sings mysteriously, about a “Yama-Yama Man,” who jumps from dark corners at night, and she dances with eight white-faced manikins about him in sprightly fright.

Daily Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), June 21, 1908, page 21.

The Yama Yama Man

With his terrible eyes and face of tan

Will get you if he can.

The Times Herald (Port Huron, Michigan), August 18, 1908, page 1.

In 1911, a copy-cat song replaced “Yama Yama Man” with “Jigaboo Man,” suggesting perhaps that some people associated the word “Jigaboo” with “bugaboo” or “bigiboo.”

The modern musical comedy of the Hough-Adams-Howard variety is not complete without an imitation of Bessie McCoy’s famous “Yama Yama Man.” In the new Chicago revue, “Miss Nobody from Starland,” seen at the Sandusky theater Thursday, the song is called “The Jigaboo Man” and it was the most tuneful of the production, while the effects were good.

The Sandusky Star-Journal (Sandusky, Ohio), April 28, 1911, page 2.

Miss Olive Vail as the headliner, won the hearts of her house with her lovely face and voice. Her rendition of ‘The Jigaboo Man’ was far away above all the other offerings of the evening, and her realistic male chorus in support with their weird costumes added largely to the success of the number.

The Fresno Morning Republican, September 28, 1911, page 13.

In 1912, someone sang the song in a high school musical program, accompanied by “Ghosts,” consistent with the song being about a “bugaboo” or “boogie man.”

Tonight the high school will give a musical entertainment. . . . The following is the program.

. . . Jig a Boo Man - Miss Allison and Ghosts.

Caney Daily Chronicle (Caney, Kansas), November 23, 1912, page 1.

Two early examples of “jigaboo” in print are not consistent with either “bugaboo” or the now more familiar sense of the word. In 1910, for example, the program of a minstrel show to be given by a Catholic boys’ club included a segment entitled, “Jigabo’s Jokes,”vi which seems similar to the use of stock names like “Jasbo” or “Sambo” as the character name of a blackface comedian. And in 1912, a notice about an upcoming performance by children in Tacoma, Washington boasted that there “will be many pretty features, from the classic dance to the “jig-a-boo.”vii Neither one of these senses of the word appear to have caught on. Some people have speculated a connection between the Irish jig dance and jigaboo, but this single reference appears to be an outlier, and not indicative of a strong - or any - connection between the two.

Jigaboo/Zigaboo

In the years immediately after the debut of “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea,” “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo” (and sometimes “Gigaboo”) supplanted the name “Ji-ji-boo.” The sense of those words also changed, from the name of the Irishman, to the name of a remote, exotic island, or country, or the name of the people native to the island.

Two baseball player nicknames indicated that people understood an association between “ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” and “Jigaboo” or “Zigaboo.” In 1914, an amateur pitcher named “Zigaboo Mayo” was slated to pitch for a team of vets against a team of brewers.viii “Zigaboo Mayo” rhymes with “Ji-ji-boo J. O.”

In 1922, a pitcher named Patrick Henry Shea joined the San Francisco Seals. In his first game with the team, one reporter made several explicit references to the song, referring to him as “Patrick Jumbo Jigiboo Jay O’Shea” and describing him as having no “rings on his fingers nor bells on his toes.”

Patrick Jumbo Jigaboo Jay O’Shea, late of New York and now of these parts, had no rings on his fingers nor bells on his toes. Neither did he have much stuff on the ball, so the Tigers managed to halve a twin-bill with the San Francisco Seals.

The San Francisco Examiner, July 30, 1922, sporting section, page 1.

In 1914, a newspaper in Memphis, Tennessee referred to the left field bleachers as “Zigaboo land.”

McBride backed up against the left field bleachers to get McDermott’s fly in the tenth inning. Had “Red” put a few more pounds to the drive it would have landed in “Zigaboo” land.

The Commercial Appeal (Memphis), May 25, 1914, page 9.

His three hits had much to do with winning his game as he eventually scored on all three occasions. His first effort was a long drive which sailed into “Zigaboo Land” on a line and entitled the “German Barron” to canter around the bases unflagged.

The Commercial Appeal (Memphis), June 29, 1914, page 12.

The expression is not defined in these two examples, but they may be the earliest known example of “Zigaboo” to refer to black people. In 1915, and again in 1919, the “negro bleachers” in the segregated seating of the Memphis baseball park were located in left field.

Separate accounts of a game played at Memphis in early 1915, for example, describe Gene Paulette’s solo home-run alternately as having been hit into “the negro bleachers” or “left field.”ix And in 1919, Pug Griffin hit a ball “full in the face and it shot out to left field with great force, apparently headed for the negro bleachers.”x Assuming those seats had been in the same location in in 1914, the references to “Zigaboo Land” in the Memphis baseball park in 1914 are the earliest known example of “Zigaboo” used to refer to black people.

In 1915, “Zigaboo” appeared in the syndicated comic strip, Lord Longbow. The weekly strip recounted the adventures and misadventures of a British military officer or explorer of some sort, whose fantastical stories took place in exotic and dangerous locations around the world.xi He captured bears with his parachute, he escaped from bears using an umbrella as a parachute, captured a python using croquet wickets, disarmed Muslims with a magnet carried in his airplane, destroyed a hoard of nomadic warriors by ascending into and steering a dust devil toward them, fought off a band of monkeys by swatting the coconuts they threw at him with a cricket bat, and once saved the island of Zigaboo from an attack by a pirate ship, earning him the admiration of the “chief Zigaboo” of the island.

“Down in the Zizaboo isles a piratical junk hove into the offing.

“When they sent boats ashore we were in no position to stand attack, so I dashed to the laundry and swiped the soap, throwing it in the water.

“The sea was shortly afoam near shore and the rascals thought they were on the rocks, so they returned to their craft, old top.

“The chief Zigaboo had previously no use for soap, but when he saw that junk hull down on the horizon he promised to keep a piece all his life as a memento of the affair, old chap.”

Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon), February 13, 1915, page 14.

A remark in the syndicated comic strip, “Boots and Her Buddies,” in 1924 made a connection between “Zigaboo” and Pacific Islanders. One woman asks another why she accepted a date with Tom, who is “homely as a Fiji Zigaboo!” and who “dances like a truck horse!” Nevertheless, she accepted the date because, “his black eyes! they go so adorably with my new chiffon frock.”

|

Ironwood Daily Globe (Ironwood, Michigan), February 28, 1924, page 9. |

In 1914, the comedy team of Claude Durkee & Billy Dayton appeared in a “Double Dutch Comedy” they called, “The King of Gigaboo,” possibly a rip-off of, or inspired by, “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea.” Durkee and Dayton do not appear to have been very successful - the advertisement for the show is the only reference to them, or their show, uncovered in researching this topic.

|

Hutchinson News (Hutchinson, Kansas), January 9, 1914, page 8. |

The transition from East Indian in the song, to people of African descent, likely came about by the characterization of the islanders on stage with the Irish “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea,” presumably played by white actors in blackface, perhaps performing the characters as stock, African or African-American characters, not as anthropologically correct depictions of East Indian or Pacific islanders. The lyrics themselves are ethnologically ambiguous, as “Mumbo Jumbo” is of African Origin, not East Indian.

The earliest known example of either “Jigaboo” or “Zigaboo” unambiguously referring to a black person appeared in 1917. Coincidentally (or not?), it appeared in a poem written by Fred D. Beneke,xii a reporter from the same newspaper in Memphis that had apparently used the expression, “Zigaboo Land,” to refer to the segregated “negro bleachers” in left field, a few years earlier.

Beneke wrote a series of war-related poems for the Commercial Appeal during World War I. One poem encouraged people who were physically unfit to serve in the military, to do their part at home by buying bonds, planting a garden, and volunteering for the Red Cross. Another was critical of German war propaganda.

Another one of Beneke’s poems spread propaganda of his own, critical of certain kinds of soldiers who were physically fit and willing to serve “with a Zigaboo regiment.” The subject of the poem is a black infantryman who explains why he’ll stick to the infantry, and avoid the Navy, Air Corps, Artillery or the Cavalry.

THE PLACE TO SERVE

Sam Green is a regular soldier man,

Of African descent;

The world is bright when Sam can fight

With a Zigaboo regiment.

Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), July 8, 1917, page 5 The Hutchinson Gazette (Hutchinson, Kansas), March 28, 1918, page 10 (beginning in March 1918, the poem was reprinted in more than a dozen newspapers in Kansas and Oklahoma).

The sports journalist, “Bugs” Baer, described a boxer named Bundy (“the champ of his race”) as a “Zigaboo” in 1920.

THE BEST FIGHTERS, by “Bugs Baer.

Battling Bundy was another rough Xmas shopper. Bat laid the fist on his constituency generously. He though that a beating was a vacation. If one man wouldn’t put the boots on another man, Bat considered that guy a miser. In barroom skirmishing there are no rules. The fight ain’t over until the black crepe is on the door bell. Bundy was a zigaboo and the champ of his race.

The Pittsburgh Press, December 9, 1920, page 32.

Newspapers in Paris, Tennessee and New Castle, Pennsylvania referred to black defendants in police and court reports as “Zigaboos” or “Jigaboos” in 1921.

|

The Parisian (Paris, Tennessee), September 30, 1921, page 2. |

|

The Parisian, November 11, 1921, page 1. |

|

New Castle Herald (Pennsylvania), August 12, 1921, page 4. |

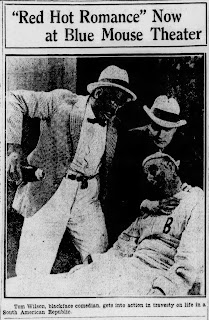

In 1922, a character in a film, entitled Red Hot Romance, was described as a “Jigaboo.” The character was played by a white actor named Tom Wilson in blackface.

[A]n unhappy young man who has to sell insurance for a year and prove that he can “make good” before he comes into his inheritance . . . is accompanied by a devoted jigaboo (ask any Yellow driver what that means) who has, I quote the subtitle, “raised him from a pup.”

Chicago Tribune, June 24, 1922, page 12.

|

“Tom Wilson, blackface comedian,” as he appeared in the film, “Red Hot Romance.” The News Tribune (Tacoma, Washington), August 23, 1922, page 8. |

“Jigaboo” and “Zigaboo,” as well as the short forms, “Jig” and “Zig,” would eventually become widely understood as pejorative expressions for a black person, that does not seem to have always been the case. White reporters writing for white-owned newspapers and white readers were not the only people to use the words.

Beginning in 1922 and continuing through 1927, an all-black company of performers, headed by Garland Howard and “Speedy” Smith, went on tour every season with a musical comedy revue entitled, “Seven-Eleven.” The “Seven-Eleven” company appeared in Boston, Kansas City, Minneapolis, Chicago, Montreal, Dayton and Baltimore, and likely many other points in between.

One of their most successful bits was a dream sequence in which the main characters were transported to “Zigaboo Land,” an inhospitable island with beautiful women, cannibals and the jealous “King Zigaboo.”

Jazz music and colored entertainers is a combination that always pleases Boston audiences, so it was not strange that the first performance of “Seven Eleven” at the Arlington Theatre last night met with the whole-hearted approbation of the Afro-Americans, who made up a large part of the audience of first-nighters. . . .

The second act is much better than the first, and shows the adventures of Jack Stovall (Speedy Smith) and Hot Stuff Jackson (Garland Howard) on the inhospitable island of Zigaboo. The dusky beauties who “shake a wicked hay stack” vamp poor Stovall until he falls into the clutches of the cannibals and is sentenced to die by King Zigaboo (Sam Cook). Just before the execution Stovall awakes to discover that he is back in the Needmore Hotel at New Orleans.

The Boston Globe, October 31, 1922, page 6.

In 1924, they were booked into Hurtig & Seamon’s theater on 125th Street in Harlem. Coincidentally, Hurtig & Seamon’s would become the Apollo Theater a decade later.xiii.

|

New York Age, May 24, 1924, page 6. |

The relationship with Hurtig & Seamon paid off. Under their management, “Seven-Eleven” joined the more prestigious Columbia Burlesque circuit in 1925, giving them more reliable work in more and better venues. They were the first all-black troupe in twenty-five years to be booked on the Columbia Circuit.

|

Pittsburgh Courier, February 7, 1925, page 8. |

Hurtig and Seamon’s all-colored show, “Seven-Eleven,” which opened yesterday afternoon at the Gayety Theater, proved one of the best entertainments of the season and was warmly received by a capacity audience. . . .

Howard and Smith showed to best advantage in “Zigaboo Land.” A crystal gazer told the two comedians that the most beautiful women in the world were in Zigaboo Land. This assertion started the two comedians on their way. Both of them were captured by King Zigaboo because they had been flirting with his wife.

. . . Hurtig and Seamon’s show is the first all-colored show to appear on the Columbia circuit in twenty-five years. The applause of the audience proved that these entertainments are popular.

Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), January 19, 1926, page 19.

“Seven Eleven,” an all-Negro musical revue featuring Mamie Smith, phonograph record star, opened last night at the Empress theater for a week’s stay. . . .

It has a book of a sort, in which the characters spend some time on a steamship levee, some more time in a lobby of a hotel that one owns, and still some more time in Zigaboo Land, a mystic place filled with weird looking animals and fat mammas who do shivery dances. The dances are none to shivery, however.

The Kansas City Star, December 4, 1927, page 5.

In 1925, Eric Waldron, a writer of the Harlem Renaissance, used “Jigaboo” in one of the earliest, unambiguous examples of “jigaboo” in print with reference to a black person.

“You known one thing,” Kit observed, “there ain’t another [n-word] in this place but you and me and the waiters. . . .”

Mistah Beauty looked indifferently about.

“Not a jigaboo,* but a whole lot o’ ofay† gals.”

. . . .

* Negro.

† White

“The Adventures of Kit Skyhead and Mistah Beauty, an All-Negro Evening in the Coloured Cabarets of New York,” Eric Waldron, Vanity Fair, Volume 24, Number 1, March 1925, page 52.

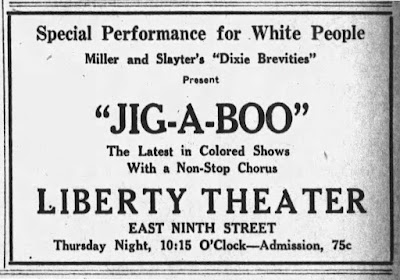

In 1928, Miller & Slayter’s “Dixie Breveties” company presented a show called “Jig-A-Boo.”

The State (Columbia, South Carolina), March 8, 1928, page 9.

In Chattanooga, they performed at the blacks-only, segregated Liberty Theater. The show went over so well that they did a “special performance for white people” only.

|

The Chattanooga News (Tennessee), March 28, 1928, page 21. |

Quintard Miller and Marcus Slayter sometimes billed themselves as, “the Aristocrat of Colored Shows.”

|

Wilmington News-Journal (Wilmington, Ohio), January 4, 1927, page 3. |

Quintard Miller was an African-American performer, producer, writer and promoter. When he was born near Chattanooga in 1895, his father was principal of the segregated “colored schools” of South Pittsburg, Tennessee. They later moved to Nashville, where Quintard’s father became the long-time editor of the black newspaper, the Nashville Globe. His older brothers were also performers. His oldest brother Irvin became a “noted vaudeville performer and theatre producer,” and his older brother Flournoy was an “entertainer, actor, lyricist, producer, and playwright,”xiv who would become one of the writers for the Amos and Andy television show in the 1950s.xv His niece (Flournoy’s daughter), Olivette Miller, would become a renowned jazz harpist and singer.xvi

Quintard Miller was acting professionally as early as 1915, in his brother, Irvin’s, company,xvii and producing his own shows in Nashville by October of 1917.xviii In early 1918, “Quintard Miller and his Cafe May Girls” joined his brother Irvin’s show, “Broadway Rastus.” By the end of the year, he was producing his own show, “Bernard’s Darktown Follies.”

|

“Darktown Follies,” The Indianapolis Sunday Star, December 15, 1918, part 6 (drama and magazine), page 1. |

|

The Indianapolis Sunday Star, December 15, 1918, part 6 (drama and magazine), page 2. |

“Bernard’s Darktown Follies” will be seen in a new edition of Quintard Miller’s wonder show, “Dixie to Broadway,” a musical comedy revue which has won him fame, at the Orpheum Theater, Wednesday, matinee and night.

The Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), November 16, 1918, page 10.

Marcus Slayter performed professionally as early as 1920, when he was in the cast of “The Smarter Set’s” “two-act jazzonian operetta,” “Bamboula.”xix In 1923, he was the manager of a performing company staging a musical comedy in Philadelphia.

“Si Ki” Big Musical Comedy in Rehearsal

On July 26, Marcus F. Slayter, the present manager of the Sandy Burns company, and a one-time member of the Billy King show, put “Si Ki,” a two-act musical comedy into rehearsal at O’Neil’s hall in Philadelphia. The producer is responsible for the book, lyrics and score, while Herman Hubbard is the stage manager. There are sixteen scenes in the piece.

The Pittsburgh Courier, August 11, 1923, page 11.

Slayter was a busy man in the fall of 1923, also staging a show called “Creole Follies” in Gibson’s New Dunbar Theatre, also in Philadelphia; perhaps his first collaboration with Quintard Miller.

The book is by Miller and Slayter, with lyrics and music by Donald Heywood, and special arrangements by W. Benton Overstreet.

The Pittsburgh Courier, September 15, 1923, page 12.

Five years later, Miller and Slayter toured together in the show called, “Jig-A-Boo.” Miller and Slayter’s personal and working relationship would be a long (and loving?) one. They moved to California together in the 1930s, where they produced floor shows at the “popular deep Central nite spot, Club Alabam.”xx In the 1940s, they lived and entertained together at a home on Denker Avenue,xxi and built a vacation home together in Val Verde,xxii a real estate development sometimes referred to as the “Black Palm Springs.”xxiii In 1953, in a local newspaper report about the pair of “ex-theatre troupers,” Miller and Slayter, spending their vacation together in their “lovely home” in Val Verde, they were described as “popular bachelors of Los Angeles.”xxiv

In the years immediately following Miller and Slayter’s “Jig-A-Boo” show, the word appears as the name of several songs; the “Jig-a-boo Jump” (1929), “Let’s Do the Jigaboo” (1930), and “Let’s Jig the Jigaboo” (1930), and “The Dance of the Jigaboo Man (1934).

Another writer of the Harlem Renaissance, Rudolph Fisher,xxv used the word “jigaboo” in his first novel, The Walls of Jericho, published in 1928. The word appears in dialogue spoken by one black man about another black man.

“Give it to Jinx,” urged a bystander. “Might stop that rattle yet --- ”

“Rattle, hell,” said Pat. “That jigaboo ain’t got a thing but the hiccoughs.”

Rudolph Fisher, The Walls of Jericho, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1928, pages 213-214.

An appendix to The Walls of Jericho, entitled “An Introduction to Contemporary Harlemese, Expurgated and Abridged,” Fisher explains the meaning of “jigaboo” as one of several, alternate synonyms of “negro.”

|

Rudolph Fisher, The Walls of Jericho, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1928, pages 213-214. |

In 1930, Langston Hughes, a “leading light” of the Harlem Renaissance,xxvi used “jigaboo” in his novel, Not Without Laughter, in dialogue among black speakers, in a scene set during World War I.

Where’s Jimboy, Annjee? In the war, I suppose! It’d be just like that big jigaboo to go and enlist first thing, whether he had to or not.

Langston Hughes, Not With Laughter, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, seventh printing, January 1945 (first printing July 25, 1930), page 320.

The black writer and anthropologist, Zora Neale Hurston,xxvii used the word “Zigaboo” in her “Story in Harlem Slang,” which appeared in the American Mercury in 1942.

In her accompanying “Glossary of Harlem Slang,” Hurston explains that “Zigaboo” means “a Negro” while “Jig,” “a corrupted shortening of zigaboo” has the same meaning. It is noteworthy that in Hurston’s gloss there is no pejorative connotation at all.

“On the Possible African Origin of Jigaboo,” Alan Dundes, Midwestern Folklore, Volume 17, Number 1, Spring 1991, pages 63-65.

The earliest suggestion that “Jigaboo” could be understood as a slur appeared the Dictionary of International Slurs (1944), in which “jigaboo: negro” appears in its list of ethnophaulisms. In 1947, a book entitled, Wartime Shipyard: A Study in Social Disunity, noted that:

The Negro was seldom even named in all-white talk except in appellations of implied derogation and antagonism, the most common being the timeworn “[n-word]” and the more recent “jigaboo” or “zigaboo,” frequently shortened to “jig” and “zig.”

Katherine Archibald, Wartime Shipyard: A Study in Social Disunity, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1947, page 61.

Conclusions

The song, “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” (1909) and the island characters on stage during the song, may be the origin of the words “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo,” in the sense of referring to a black person. The pre-existing words, “Gigaboo” and “Zigaboo,” with other meanings, may have influenced the change from “Ji-ji-boo” to “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo.” Early uses of “Zigaboo” and “Jigaboo,” with reference to exotic island locations, or with reference back to the character, “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea,” suggest a connection between those words and that song. The lack of any example of those words, in this sense of the words,and the pre-existence of those words (or something like them) in a completely different sense, further support the conclusion.

Other researchers have made other suggestions, but those appear to be mostly speculation, based on single examples of arguably similar words in an African language, with an arguably similar sense, but without supporting, documentary evidence. They were also handicapped by writing at a time before online, searchable archives made it possible to more easily find more early examples of early use, and follow more threads to make more connections, and draw more supportable conclusions.

Clarence Major, a professor of twentieth century American literature at the University of California at Davis, asserted that “jigaboo” derives from a Bantu word, tshikabo, meaning “a meek or servile person.”xxviii He also suggested the word was in use from the 1630s through the 1950s, and that it “was always pejorative.” The lack of any pre-1909 evidence of use, and the existence of non-pejorative use before the 1940s, however, call his conclusions into question.

In the absence of any other “plausible explanation,” the anthropologist and folklorist, Alan Dundes,xxix believed that “jigaboo” may have been borrowed from another African language, Igbo.xxx His argument would be stronger if there were even one intermediate example of something like the word “jigaboo” between 1808 (when the importation of slaves from Africa into the United States ended) and 1909 (when “Ji-ji-boo J. O’Shea” was first performed on stage).

The apparent origins of the words as a variant of “Ji-ji-boo,” from the popular song, as outlined above, may be the “plausible explanation” that would have obviated Dundes’ and Major’s speculations.

You be the judge.

ADDENDUM (June 6, 2023): More than a decade after "Rings on My Fingers" featured the lyrics, "Ji-ji-boo J. O'Shea," the name "Ji-Ji-Boo" was revived as the title of the popular dance tune, "Ji-Ji-Boo," by Willy White, Harry White and Joseph Meyer. Like the earlier song, "Ji-Ji-Boo" was about a sailor stranded on a "tropic isle." But this time, "Ji-Ji-Boo" was the name of a "Fiji Queen," not a title bestowed on the sailor. For more on this later song, see my post, "Ji-Ji-Boo 2 - the Etymology of Jigaboo (an Adendum)."

i “Public Domain Super Heroes, Gigaboo,” https://pdsh.fandom.com/wiki/Gigaboo

ii Interestingly, although volume II of The Apollo lists “The King of the Cannibal Islands” as “Air - Vulcan’s Cave” (sung to the tune of “Vulcan’s Cave”), volume 3 of The Apollo (1830) lists a song called “The Wake of Teddy the Tiler” as being sung to the tune of “The King of the Cannibal Islands.”

iii The reference to “Zigaboo” appeared in a Kansas newspaper, reprinted from an Ohio newspaper, but may have been about Kansans visiting Ohio - why else would the small society item from Ohio be reprinted in Kansas?

iv In his inaugural address, Governor Leedy said, “With a cheerful audacity that almost challenges admiration, Grub Street scribblers on a venal press which panders to the most vicious instincts of semi-civilized colonies like New York City and Chicago, with semi-barbaric squalor at the apex and semi-barbaric squalor at the base of their social life, have offered puny and presumptuous criticism of those whose shoestring they are not worthy to unloose. . . . They well know that Kansas was a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night before an oppressed people in the Nation’s darkest hour. We shall keep those fires alight in our camps, and that smoke ascending from our hilltops till this is indeed a government of the people and for the people and by the people.” Buffalo Courier, January 15, 1897,

v Centralia Fireside Guard (Centralia, Missouri), November 4, 1910, page 4.

vi Belvidere Daily Republican (Belvidere, Illinois), May 9, 1910, page 4.

vii The News Tribune (Tacoma, Washington), November 20, 1912, page 4.

viii Detroit Free Press, May 24, 1914, page 20.

ix Compare, The Commercial Appeal (Memphis), April 30, 1915, page 11 (Gene Paulette made the first Nashville run singlehanded when he lifted a homer into the left field seats in the fourth inning.”) with, The Nashville Banner (Nashville), April 30, 1915, page 10 (“Paulette, catching one of Merritt’s inshoots, drove it high up into the negro bleachers for a home run when two were out.”).

x The Commercial Appeal (Memphis), June 2, 1919, page 10.

xi Lord Longbow was first written by Richard Thain in the Chicago Daily News in 1907. After a hiatus, it was revived by a cartoonist named Rankin in 1909. It was syndicated beginning in about 1911. https://newspapercomicstripsblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/20/lord-longbow/

xii Frederick D. Beneke joined the editorial board of the Commercial Appeal after moving to Memphis from Clinton, Arkansas. His reporting from the scene of a deadly Louisville & Nashville train accident, that the ambulance crews were removing dead victims before wounded victims, helped spur reforms in ambulance practice. He was later the secretary of the Mississippi River Flood Control Association and the National Rivers and Harbors Congress. “Death Claims Fred D. Beneke, Valley Flood Control Expert,” The Commercial Appeal (Memphis), August 4, 1948, page 1.

xiii https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/manhattan/harlem-apollo-theatre-mecca-black-showbiz-article-1.789788

xiv https://aaregistry.org/story/flournoy-miller-vaudeville-playwright-born/

xv Overview of the Flournoy Miller Collection, New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts. https://archives.nypl.org/scm/20858

xvi https://aaregistry.org/story/olivette-miller-jazz-harpist-born/

xvii The Tennessean (Nashville), May 9, 1915, page 21 (“Irvine Miller and Esther Bigeou Miller, his wife, will return here for a two days’ engagement at the Lincoln Monday and Tuesday in ‘Mr. Ragtime,’ written by Miller. . . . . Quintard Miller, a brother, also returns with the company.”).

xviii Nashville Globe, October 12, 1917, page 8 (“Manager Miller. Quintard Miller who is putting on the shows at the Lincoln seems to know what he is doing. Having had an opportunity of seeing and knowing the leading colored performers, he is in a good position to pick the acts that will please Nashville theatre-goers.”).

xix The Richmond Planet (Virginia), October 23, 1920, page 2.

xx California Eagle (Los Angeles), July 10, 1936, page 10.

xxi California Eagle, August 22, 1946, page 12 (“Messrs. Q. Miller and M. Slayter entertained Friday evening at dinner in their Denker ave. apt. . . .”).

xxii California Eagle, February 3, 1949, page 12 (“Messrs. Quinton Miller and Marcus Slayter spent the weekend at their newly built home in Val Verde.”).

xxiii https://culturaldaily.com/val-verde-black-palm-springs/

xxiv The Signal (Santa Clarita, California), August 6, 1953, page 8.

xxv https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/fisher-rudolph-1897-1934/

xxvi https://www.biography.com/news/langston-hughes-harlem-renaissance

xxvii https://wams.nyhistory.org/confidence-and-crises/jazz-age/zora-neale-hurston/

xxviii Clarence Major, Juba to Jive, New York, Penguin Books, 1994, page 258; William Safire, No Uncertain Terms, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2003, page 8.

xxix https://alumni.berkeley.edu/california-magazine/just-in/2021-08-25/lord-lores-papers-famed-folklorist-alan-dundes-open-public

xxx Midwestern Folklore, Volume 17, Number 1, Spring 1991 (“I believe the term ultimately derives from a common root found in Nigritic languages in Nigeria. In Igbo, for example, we have ‘ezi,’ which means ‘goodness, truth, kindness’ and which yields an adjectival form ‘ezigbo,’ signifying ‘kind, good, true.’ . . . It is not at all difficult to imagine that Euro-Americans, lacking any knowledge of any Nigerian languages might have seized upon ‘ezigbo’ as an appropriate term for blacks in general. To be sure, in Euro-American racist usage, the term became one of opprobrium, having lost completely its original sense of ‘good and kind.’ But this semantic shift notwithstanding, it would appear that we have one more Africanism to be added to the long list of such borrowings in American culture.”).