NIB . . . A very small piece or quantity of anything.

The English Dialect Dictionary, Volume 4, M-Q, London, H. Frowde, 1903.

NIBS . . . An important or self-important person - usually in the phrases his nibs or her nibs as if a title of honor.

A rumor circulating on social media platforms since at least 2015 suggests that the name of Twizzlers’ black licorice-flavored candy, “Nibs,” is a shortened form of “n[-word] babies.” This may not be true, however, as a race-neutral sense of the word “Nib,” meaning a “very small piece or quantity of anything,” would explain the choice of the name, without resort to a speculative, racist acronym. Licorice “Nibs” are about the same size and color as “cocoa nibs” and roasted “coffee nibs,” which were known ingredients in the candy and foot processing fields when “Nibs” took their name. Any passing similarity to the word “n[-word] babies” may be mere coincidence.

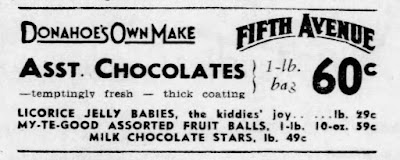

The rumor, even if false, is rooted in at least one fact. Small, baby-shaped licorice candies have, in fact, been offered for sale in the United States since at least the 1880s. Those candies were frequently referred to as “n[-word] babies.” A race-neutral, alternate name, “licorice babies,” was at least as common as the problematic name by the 1900s, and became increasingly dominant as the years passed. Twizzlers’ “Nibs,” however, are not and never have been baby-shaped, and there’s no indication that they were ever marketed, or referred, to as “N[-word] Babies.”

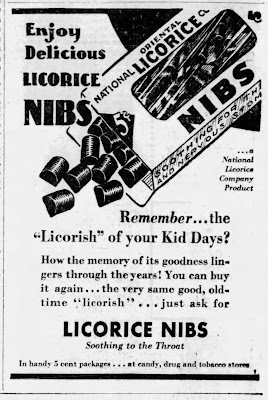

Surprisingly, perhaps, if “Nibs” ever has been marketed in what might now be seen as a racially inappropriate name, it was in relation to Asians, not African-Americans. Beginning in about 1930, “Nibs” were rebranded as “Oriental Nibs.” “Oriental,” in this case, likely alluded to the licorice root being widely harvested in the Middle East, as opposed to the Far East, but that did not stop some people from associating them with Asia.

NIBS

TWIZZLERS brand NIBS are manufactured by Hershey, the chocolate company, who bought out TWIZZLERS’ parent company, Y&S in the 1970s. Y&S stood for Young & Smylie, a licorice company from Brooklyn, New York, that dates back to 1845.

Young & Smylie’s products included, Acme Licorice Pellets, a variety of wafers, lozenges and sticks, with many of them sold under the Y&S brand name. |

Young & Smylie advertisement, Grand Trunk RY Company of Canada, Official Time Table, 1885. |

In 1902, Young & Smylie joined forces with several other licorice companies, H. W. Petherbridge, F. B. & V. P. Scudder, Stamford Manufacturing, and MacAndrews & Forbes, to form

the National Licorice Company, with Charles A. Smylie as President. National Licorice changed its name to Y&S in 1968.

The National Licorice Company became entangled in anti-trust litigation, as part of the so-called “Licorice Trust.” They were also implicated in the “Tobacco Trust” litigation, since licorice paste was one of the main ingredients in plug chewing tobacco.

|

The Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1907, page 2. |

The National Licorice Company introduced NIBS brand licorice bits in 1923.

|

Des Moines Tribune, November 8, 1923, page 9. |

Licorice Nibs Here.

Harry S. Hays, the licorice man, is in the city introducing a new confection called Licorice Nibs. It’s the same licorice that we all loved so much when we were youngsters and with many of us the taste has never disappeared, only that we remember licorice as a stick and our personal vanity keeps us from buying and chewing licorice sticks. Now that objection is removed. Licorice Nibs, is simply our old friend licorice in a new form - in small square bits - attractive to look at and attractively packaged.

The Cedar Rapids Gazette, October 29, 1923, page 10.

Licorice NIBS are very small pieces of candy, which may explain why they were given a name that means, in one sense of the word “nibs,” a “very small piece or quantity of anything.” The word was applied to “small nibs of turfy loam,”i a “small nib of lime,”ii “small nibs of charcoal,”iii or “small nibs of coal.”iv

The word “nibs” had been used with a different type of licorice candy several years earlier. Significantly, with respect to the suggestion that NIBS is short for “N[-word] Babies”), these earlier licorice “nibs” were apparently not black on the outside, so there would have been no particular reason to refer to them by that name. The licorice was encased within “little tubes of crystal sugar,” perhaps like Good ‘n’ Plenty or licorice pastels.

Licorice Nibs. - Dainty little tubes of crystal sugar and filled with delicious licorice candy. Very tasty for those who like good licorice candy. Lb. 25c.

Asbury Park Press (Asbury Park, New Jersey), November 12, 1915, page 5.

There were also at least two other types of “nibs” commonly used in food production. Licorice NIBS are about the same size, and of a similar color (or shade), as coffee nibs and cocoa nibs, so it would not have been a stretch to apply the same name to small pieces of licorice.

Coffee Nibs.

Each [coffee] berry has two seeds usually called coffee beans or coffee nibs, and these are the coffee of commerce.

Webster’s Weekly (Reidsville, North Carolina), November 21, 1901, page 3.

Here the coffee nibs, or “beans,” have been shoveled into heaps, to dry in the hot sun.

Visual Education, Volume 4, Number 1, January 1923, page 48.

Cocoa Nibs.

To prepare the [cocoa] seeds for use, they are roasted, crushed, and winnowed to remove the husks. The husks are known in commerce as “shells”; the crushed seeds are called “cocoa-nibs”; cocoa-nibs ground to a paste makes “flaked cocoa”; flaked cocoa mixed with sugar and aromatized is “chocolate.”

Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Universal Exposition of 1889 at Paris, Washington DC, Government Printing Office, 1891, page 713.

The Story of Chocolate and Cocoa, Hershey, Pennsylvania, Hershey Chocolate Corporation, 1926, pages 11, 19, 20.

The expression, “Cocoa Nibs,” was even used in a marketing campaign for cocoa in England. In the 1910s and ’20s, Rowntree’s (who would later develop the “Kit-Kat” bar), marketed its “Elect Cocoa” with mascots known as the “Cocoa Nibs.”

|

The Poster, Volume 13, Number 5, May 1, 1922, page 45. |

The Cocoa Nibs held out a cup,

To cheer the poor old fellow up.

“Drink lots of this, and when you’ve done,

“You’ll have more colour than the sun.”

Lincolnshire Echo (Lincoln, England), December 18, 1919, page 2.

“His Nibs”

The brand name of licorice NIBS may not be based on “N[-word] Babies,” but the word “nibs” could be insulting in one sense of the word. “His/Her Nibs” was used ironically, as a mock-aristocratic title, to refer to an “important or self-important person.” It was frequently expanded to “His/Her Royal Nibs” or, when used with respect to someone from the “East” (Middle or Far), “His/Her Oriental Nibs.”

For example, the King of Hawaii.v

The King of England.

His Royal nibs, King Ed. the VII, had finished reading the evening papers that had been brought in by a page dressed in such gorgeous livery that so far as clothes went even General Miles would look like three worn ten cent pieces by comparison.

The Elk City Enterprise (Elk City, Kansas), March 29, 1901, page 3.

A fictional Mayor.

By Clothes-line Press. Washington D. C., March 19. - The pennyroyal train bearing His Royal Nibs, Lord Helpus ‘Rastus, Knight of the Golden Fleece, arrived at the Grand Central station here at 8:30 A. M. There was a large crowd at the station and several locomotives made considerable noise by way of salute. His Royal Nibs went to the Shoreham for Breakfast.

The Buffalo Times (Buffalo, New York), March 19, 1902, page 1.

A stage play, in which the title character, “His Royal Nibs,” was Satan - King of the Underworld.

|

The San Francisco Call, April 18, 1904, page 12. |

Among the thousands of references to “His/Her Nibs” or “His/Her Royal Nibs,” there are a small handful (a few nibs?) of examples of “His/Her Oriental Nibs,” when the person being referred to is from the “East.”

Sunset Cox has had an interview with the Sultan of Turkey, during which they discussed the tariff question. As his Oriental Nibs is reported to have about two hundred wives, he would doubtless find the speech of the witty ex-Congressman on the tariff on corsets peculiarly interesting.

Humboldt Times (Humboldt, California), September 15, 1885, page 2.

When the Shah visited England, and went to the Gaiety Theater, London, to witness the ballet, his royal oriental nibs was filled with astonishment to find those light-heeled nymphs of the footlights arrayed very much like the ladies of his harem, back home in Tehran.

The Chicago Inter-Ocean, November 27, 1887, page 17.

His Oriental Nibs, Hadji Hassein Ghooly Khan, Embassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary from Nasr-Ed-Din, Shah-in-Shah (King-of-Kings) of Persia, to this part of the “Wild and Wooly West,” has packed his diplomatic portfolio and departed these shores, without any leave-taking of the President or the State Department.

The National Tribune (Washington DC), July 18, 1889, page 5.

Constantinople, November 24. - United States Charge d’Affairs Griscom called upon Tewifik Pasha, Minister for Foreign Affairs, yesterday to urge a settlement of the difficulty in relation to granting of an exaquatur to Dr. Thomas H. Norton, who some time ago was appointed by President McKinley to establish a consulate at Harpoot. The Porte is firm in its refusal to grant an exequatur.

Stockton Daily Evening Record (Stockton, California), November 24, 1900, page 8.

He says he can’t abide his Oriental Nibs, but as [the Hindu mystic, Swami Lal Singh] is a friend of Mrs. Stevenson’s he has to swallow him.

“‘Where’s Emily?’A Serial Mystery Story,” Carolyn Wells, Herald and Review (Decatur, Illinois), September 27, 1927, page 4.

“Where’s Emily?” would again be widely published throughout the United States in 1930. That same year, the National Licorice Company’s hometown newspaper, The New York Daily News, exposed a fake-prince’s return to New York under an assumed name, several years after first being deported under his previous assumed name. He was apparently a sort of high-end gigolo, ingratiating himself with wealthy women who bathed in the glow of his exotic fake-titles and regal bearing.

He did not choose this title for himself, but the New York Daily News referred to him as “his royal Oriental Nibs.”

Whispers of the Oriental potentate’s presence came to The News. This investigator took one look and, strangely enough, found Prince Pasha to bear a remarkably close resemblance to none other than the quince prince Zerdecheno of 1922, 1924 and 1925; formerly exposed by The News as an erstwhile pants presser, book salesman, hotel heat and general all-around four-flusher.

Deported by the immigration authorities after his last visit here in 1925, when The News had exposed and nipped his royal pretensions for the second time, the self-styled prince of Kurdistan and scion of the Pharaohs has bounced back again with a new title, but evidently with the same old tricks up his sleeve. . . .

A request to see the passport brought a laconic, “Some othair day - later, perhaps,” from his royal, Oriental nibs.

The New York Daily News, March 10, 1930, page 3.

This time he would get to stay in the United States, but only after finally admitting (and proving) that he had been born in Detroit.

But that didn’t end his charade. A decade or so later, he was hauled into court on charges of disorderly conduct, related to a fight with the husband of one of his companions during her divorce proceedings.

A cane-swinging duelvi over red-headed Irene Hendy, above, mother of a 15-year old boy, caused the self-appointed Emir of Kurdistan to be presented at court himself in Long Island City.

El Paso Times (Texas), The Sunday Home Magazine, September 20, 1942.

He was found not guilty, in part on the strength of a love letter from his married girlfriend - or ex-girlfriend; during the trial she referred to him as an “imbecile.” A reporter who recognized him during the trial quoted him as having said,

“It is humiliating to acknowledge I was born in Detroit.”

“Oriental Nibs”

By the end of 1930, the National Licorice Company had rebranded its NIBS as “Oriental” NIBS. Was the change an allusion to the mock- aristocratic sense of “His Nibs”? Or simply an added element of exoticism for marketing purposes? Was the change influenced by a fake Turkish “Prince” who was in the news in 1930 and 1931? Or reprints of “Where’s Emily?” It’s not clear why the National Licorice Company rebranded “Nibs” as “Oriental” NIBS that year, but the new name was at least suggestive of “His Oriental Nibs,” and of the “Oriental” origins of licorice, whether they knew it or not.

|

Cedar Rapids Gazette, November 1, 1923, page 8. |

When introduced in 1923, National Licorice’s NIBS featured images of Egyptian pyramids and palm trees on its packaging. If that seems kinda random, it might be explained by the fact that the world was then in the grips of “Tut-mania,” in the wake of the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in November 1922 by Howard Carter and The Earl of Carnarvon.

King Tut’s name was “plastered” “here, there ‘n everywhere” in marketing and advertising the following year.

The “King Tut” label is going to be plastered on half a hundred articles of merchandise this summer. . . . “King Tut” dresses, “King Tut” suits for men, “King Tut” marcelle waves, “King Tut” candies, “King Tut” labels for canned fruit and vegetables, “King Tut” patent medicines, “King Tut” corn remedy, are among the things either already or soon to be placed on the market . . . .

The Columbus Telegram (Columbus, Nebraska), April 19, 1923, page 3.

|

International Confectioner, March 1923, page 49. |

Whether National Licorice had this in mind or not, King Tut’s name was even more appropriate for use with respect to its licorice candy, than merely reflecting the King Tut-obsessed Zeitgeist, as was the case with most other products.

Even the famous King Tut was tucked away with licorice root in his tomb.

Chicago Tribune, January 11, 1935, page 18.

|

The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), June 22, 1953, page 23. |

Later NIBS packaging also featured images of camels, which were directly related to the history of cultivating licorice. At one time, much of the licorice imported to the United States was transported by camel from its source to initial processing facilities.

The principal articles of export from Smyrna to the United States are licorice root, emery stone, figs, opium, canary seed, carpets and rugs . . . . During the last quarter nearly $50,000 of licorice root has been sent to America. . . . The Stamford manufacturing company of Connecticut is a large exporter of this root. It comes to Smyrna in huge bales loaded on camels.

Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut), November 27, 1885, page 1.

National Licorice had the good sense not to use the name of King Tut, just King Tut-adjacent, Egyptian imagery, so its packaging remained relevant even after King Tut faded from the headlines.

In about 1930, the National Licorice Company rebranded NIBS as “Oriental” NIBS. Although the word “Oriental” has fallen into disfavor, and might be interpreted as problematic if used today, at the time, it was understood as referring to something from the “East” (the word comes ultimately from Latin, orientalis, “of or belonging to the east”vii). The word was most frequently used with respect to the Far East, but was also used with respect to the Middle East.

|

Salt Lake Telegram (Utah), December 20, 1930, page 25. |

|

The Ottawa Citizen (Ottawa, Ontario), September 25, 1931, page 20. |

|

The Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), May 10, 1935, page 8. |

Although the pyramids and camels were strictly Middle Eastern, another element of the packaging may have been more suggestive of the Far East. The font used for the word “Oriental” on NIBS’ packaging seems similar to stylistic “Chinese” fonts, like those known as Mandarin or Wonton.

Although originally “Oriental” only in the Middle Eastern sense, some people associated “Oriental” NIBS fondly with the Far East. A Chinese family from New York City, for example, celebrated “Chinese New Year” with “Oriental licorice . . . Nibs.” When they moved to Florida, and couldn’t find them in the stores, so they wrote to the newspaper for advice in where to find them.

Chinese of Brevard:

Happy New Year to All.

We are a Chinese family from New York. Our family tradition around New Year’s has been to surprise each other with miniature packages of goodies as candied ginger, lichee nuts and Oriental licorice. We are well supplied with the first two items but have been unable to find a particular licorice brand called Nibs. Can you find them for us? And may the year 4667, the Year of the Fowl, bring you prosperity.

Ling Tsun, Indian Harbour Beach

Florida Today (Cocoa, Florida), February 14, 1969, page 1C.

“Licorice Babies”/“N[-word] Babies”

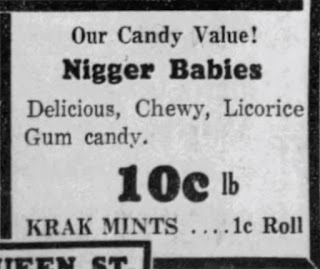

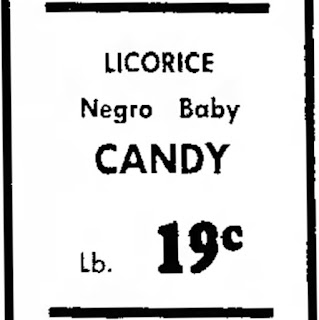

TWIZZLERS’ NIBS may not have been originally called “N[-word] Babies,” but there were, in fact, licorice flavored candies that were called “N[-word] Babies,” from at least as early as 1883.

J. B. Whitehill’s store is headquarters for fancy and plain candies, such as . . . n[-word babies, O. F. L. drops, gum babies, licorice drops, mint lozengers, O. H. drops and stick candies of all kinds.

The Jeffersonian-Democrat (Brookville, Pennsylvania), October 24, 1883, page 3.

This early example does not unambiguously show that the candies were baby-shaped; nor does one a few years later, although the differentiation between “licorice drops” and “n[-word] babies” suggests that perhaps they were.

Special Sale of Candy.

Mixed candy . . . red hots, cocoa beans, maple beans, cachone, cinnamon imperials at 50c per box or 15c per lb: licorice drops, n[-word] babies, peanut bar, maple sugar, 10c per lb. . . .

Davenport Morning Star (Davenport, Iowa), November 29, 1890, page 4.

A few years later, another example more directly states that the candies are “in the form of” babies.

CHILDREN GET SICK.

They Buy All Sorts of Confections and Trouble Results.

. . . The youngsters in these days have, pennies, nickels and even dimes, and they are not slow in imitating their elders by way of astonishing their inner man with all sorts of indigestible things. . . . Various kinds of gaudily wrapped gum, warranted to cure dyspepsia, headache, dizziness, etc.; licorice in the form of n[-word] babies, or long black sticks that look as inviting as railroad spikes or cold weinerwurst . . . .

Quad-City Times (Davenport, Iowa), February 10, 1894, page 1.

Early references to the candy (before 1900) all use the name, “n[-word] babies,” whereas after 1900, the name, “licorice babies” seems to have been used at least as often, and to have become increasingly dominant over the years.

The booby prize, which was a small licorice baby, was won by Miss Clara Kirchner and Geo. A. McGrath.

The Marion Star (Marion, Ohio), January 31, 1900, page 8.

Licorice babies, by any name, became part of the pop-culture, beyond the candy. In 1901, Mose Gumble wrote the song, “I Loves My Licorice Baby,” although n this instance (presumably), the “Licorice Baby” was a black woman, not the candy.

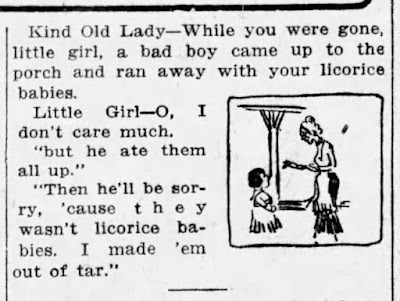

A widely circulated, viral joke in the 1910s called them “licorice babies.”

She Didn’t Care

Kind Old Lady - While you were gone, little girl, a bad boy came up to the porch and ran away with your licorice babies.

Little Girl - Oh, I don’t care much.

Kind Old Lady - But he ate them all up.

Little Girl - Then he’ll be sorry, ‘cause they wasn’t licorice babies. I made ‘em out of tar.

Los Angeles Evening Express, August 14, 1914, page 12.

|

The Boston Globe, August 20, 1914, page 14. |

In Camden, New Jersey, the home of the MacAndrews & Forbes licorice manufacturing plant, the company’s sports teams (baseball, basketball, and bowling) were all known as the “Licorice Babies,” and their baseball team played at “Licorice Ball Park.”

“Licorice babies” were the focus of a game played at children’s parties, as described Mrs. Elizabeth Thompson’s “Heart and Home Problems” advice column.

You could have small licorice candy babies secreted all over the rooms and have a hunt and give a small prize to the one who discovers the greatest number.

The Evening News (Wilkes-Barrre, Pennsylvania), October 14, 1913, page 7.

Although sometimes, the game went by a different name.

A “n[-word] baby” hunt was one of the features of the evening. Miss Rhea Jones won the first prize and Harry Holloway the booby.

The Piqua Daily Call (Piqua, Ohio), August 28, 1903, page 8.

But even where race-neutral name was used for the candy, the game might go by a different racially problematic name.

Music and charades and a “coon hunt” with the little licorice babies as the trophies of the hunt, made a deal of merriment after a business meeting, and before a dainty supper.

The Hutchinson Gazette (Hutchinson, Kansas), May 13, 1914, page 6.

In a syndicated children’s story, the child-protagonists, Nick and Nancy, ran across “N[-word] Babies” in “Sugar Plum land.”

|

| The Tulsa Tribune (Tulsa, Oklahoma), May 27, 1923, Magazine Section. |

The little black men were licorice n[-word]-babies and their wig-wams were empty ice-cream cones turned upside down!

The Richmond Item (Richmond, Indiana), April 8, 1923, page 8.

A few years later, in another syndicated children’s story, the “Tinymites” got into a marshmallow fight with the “Goofy Goos” in the “gum drop hills.” Two episodes later, we learn that the “Goofy Goos” are actually “licorice babies.”

|

|

“The Tinymites,” story by Hal Cochran and pictures by Knick, Santa Ana Register (Santa Ana, California), July 27, 1927, page 13. |

“King Lollipop” acts as peacemaker.

|

Santa Ana Register, July 28, 1927, page 13. |

“We’re Licorice candy,” one replied. “In candy stores we’re often spied. Of course we’re very harmless, we bring no cause for fear.”

The Coppy laughed aloud and said, “You all know how to raise much Ned. I think you fought a dandy fight with us a while ago.” A licorice baby, ‘mid a grin, replied, “We did not hope to win.”

Santa Ana Register, July 29, 1927, page 27.

Baby-shaped, licorice candy would continue being sold under a variety of names, some neutral, some bad or worse.

|

The Pittsburgh Press, September 29, 1932, page 19. |

|

The Life (Berwyn, Illinois), January 19, 1934, page 3. |

|

Lancaster New Era (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), July 27, 1934, page 6.

|

|

Hanover Evening Sun (Hanover, Pennsylvania), June 2, 1938, page 2.

|

|

Harlan News Advertiser (Harlan, Iowa), June 21, 1955, page 13. |

|

The Pittsburgh Press, September 23, 1947, page 4. |

Even some non-baby shaped candy were given race-conscious names.

|

Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario), September 23, 1931, page 6. |

The names used varied by place and time. There are a few references to licorice babies referred to as “tar babies” from the 1920s through the 1950s.

A penny . . . would buy ten licorice tar-babies at the grocer’s - and the grocer took that penny as though he wanted it.

The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), April 2, 1925, page 10.

|

The Wagoner Tribuner (Wagoner, Oklahoma), April 28, 1959, page 4.viii |

In Canada, they reportedly dropped “N[-word] Babies” in favor of the supposedly less objectionable (?) “Sambos,” which was apparently still in use in the 1980s - “it’s OK, it’s harmless, it’s French! And besides, it could be worse” (paraphrasing the President of the Company).

Times change. Observer received a package of Nutty Club Licorice Kids from a reader this week. What worried her was the word “Sambos,” also in large type, on the front of the packet.

What’s this? Shades of the golliwog? Racism rearing its ugly head on a candy wrapper?

Licorice Kids are made by Scott-Bathgate, which has plants in Vancouver, Winnipeg and Toronto. Company president Jim Burt was unrepentant: “Sambos? Oh, Sambos. Licorice Kids. Sambos is the French translation for Licorice Kids. It’s as simple as that.”

. . . “French Canadians Know them as Sambos,” said Burt. “And we don’t use a Parisian French in the world of candies. No, we haven’t had any complaints.”

Burt pointed out that long, long ago Licorice Kids used to be known as “N[-word] Babies.”

By comparison, Sambos seems almost harmless.

The Vancouver Sun (Vancouver, British Columbia), March 20, 1982, page E2.

Bigger “Licorice”

Whereas small, licorice candy babies were sometimes referred to as black children, black people were sometimes referred to as “licorice.” Although not as common as the ubiquitous “dusky,” “sable,” or “chocolate,” “licorice” was a word occasionally used by writers casting about for more variety in descriptive terms for the skin tone of black people. The heavyweight fighters, Jack Johnson and Sam Langford, for example, were big hunks, chunks, or sticks of licorice.

In 1910, the white fighter Larry McLean put the kibosh on any rumors that he might assume the mantel of the “White Hope” to fight the champion, Jack Johnson - he was afraid. His fears may have been founded in reality, but he claimed to have reached his decision in a dream.

“I dreamed that I was matched with the big cloud. I was pleased with the idea, for the purse was a big one and even the losing end looked pretty good to me. . . . But the fight was to come off in a week and I soon saw that I would need more training than I could possibly get in that length of time. . . .

“Finally the night of the fight arrived and I knew that I did not have a chance. I cannot describe my sensations as the time came for leaving the gymnasium for the ringside. I was not physically afraid, but I could not endure the thought of being crumpled up on the floor or the ring with that enormous hunk of licorice standing over me, grinning. . . . I shall never place myself in such a position again. It seemed like a year that I was training for that fight and two years that I was waiting to hear from the tar-baby. That is the closest that I will ever come to fighting Johnson.”

The Cincinnati Enquirer, August 14, 1910, Sports, page 2.

One week later, Sam Langford, perhaps the greatest fighter never to win a title, was preparing for a fight in Boston. He was widely known as the “Boston Tar Baby,” but was referred to by a few other choice names on occasion.

Two large chocolate drops, Sam Langford and Joe Jeanette, will mix before the Armory Athletic club in Boston on September 12. Both of these bruisers are big fellows, but it looks like “cream” for Langford, the Boston tar baby, otherwise known as the big stick of licorice.

The Oregon Daily Journal, Portland, Oregon, August 21, 1910, Section 3, page 9.

Sam Langford, the Boston chunk of licorice, can still clamber through the ropes of a prize ring and slam an ordinary fighter into insensibility. But Sambo is nearly through as a scrapper. An account of a bout Langford fought with Jack Thompson in New York the other night says the Boston tar baby had so much excess weight amidships that he resembled a balloon.

The Washington Times (Washington DC), April 12, 1917, page 10.

White sportswriters were not the only ones applying the descriptor to black people. The groundbreaking black entertainer, “Black Carl” (whose real name was Edward Johnson), had a long career as a magician, theatrical agent and for twenty-five years, the chief doorman of New York City’s Metropolitan Opera company.

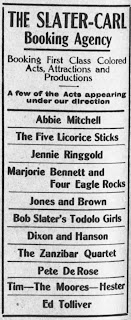

Black Carl had a decades-long career as a magician, beginning in his state of Kansas in the 1890s. Later in his career, he transitioned into theatrical management. One of the many black acts he managed was called the “Five Licorice Sticks,” a name frequently mentioned and reported on in New York’s black-owned and operated newspaper, The Age.

|

The New York Age, August 3, 1911, page 6. |

“The Five Licorice Sticks,” a quintette of singers and dancers headed by Nettie Glenn will make a big impression with their plantation groupings with the real Southern atmosphere.

Buffalo Courier (Buffalo, New York), October 23, 1910, page 76.

|

The LaCrosse Tribune (LaCrosse, Wisconsin), August 27, 1910, page 2. |

|

The Gazette (Montreal, Ontario), October 29, 1910, page 13. |

Black Carl, Nettie Glenn and the Five Licorice Sticks worked at a time when black entertainers were increasingly making inroads in a field of entertainment that had long been dominated by fake, black entertainers, played by white performers in blackface. Black Carl was a pioneer as a black musician and talent agent. The Five Licorice Sticks were, for the most part (apart from Nettie Glenn), anonymous and apparently interchangeable. But they and their contemporaries deserve credit for carving out careers for themselves at a time when it was more difficult to get your foot in the door, ultimately reducing demand for blackface entertainment, and finally putting them out of business, by offering the real McCoy.

Other “N[-word] Babies.”

The expression, “N[-word] Babies,” had a long history in other contexts, long before it was used as one of the names of baby-shaped, licorice candy. It was used to refer to actual babies, certain kinds of baby dolls, and to a variety of target, ball-throwing games. You can learn more about the history of throwing games by that, and other names, in my upcoming post, a link to which will be added here when it is posted.

|

The Yale Record, Volume 17, Number 14, May 11, 1888, page 158. |

i Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (London), August 16, 1885, page 11.

ii Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (London), July 3, 1881, page 11.

iii Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (London), July 6, 1884, page 11.

iv The Western Times (Exeter, England), July 18, 1876, page 3.

v For an unrelated connection between the King of Hawaii and the origin of the expression, “Hokey Pokey,” in musical comedy about cannibals, see my post, “Hokey Pokey” and Madame Boki - Hawaiian Royalty and the History and Origin of “Hokey Pokey.” https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2022/04/hokey-pokey-and-madame-boki-hawaiian.html

vi The expression, “to raise Cain,” may have been influenced by a well-known joke about raising one’s physical cane in anger. See my post, “Sticks and Canes May Break My Bones - a Battered History and Etymology of “Raising Cain” and “Shake a Stick.” https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2016/03/sticks-and-canes-may-break-my-bones.html

vii https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=oriental

viii See also, The Morning Post (Camden, New Jersey), December 13, 1928, page 21 (“Tar Baby” in list of candies for sale).