Twenty-Three,

Skidoo!

The early-twentieth century slang

expression, “twenty-three,” meaning, “get lost” or “take a hike,” dates to at

least 1899. It may sound far-fetched, but

circumstantial evidence suggests that it was derived from the beheading scene

at the end of Charles Dickens’, A Tale of Two Cities.

The hero, Sydney Carton, is the

twenty-third person in line for the guillotine; the knitting women in the crowd

count off each execution; “Twenty-three!”

He’s gone.

“Skidoo” appeared in print as

early as 1904 meaning, “to leave quickly;” but had also been the name of a

racing boat since 1901. The fact that

the race-related usage, perhaps suggestive of going fast, is consistent with the meaning of the slang expression, may indicate

that “skidoo” was known as early as 1901. Similarities between the sound and meaning of

“skidoo” and “skedaddle”

(which dates to just prior to the Civil War) suggest that “skidoo” was derived

from skedaddle. Three, short-lived

euphemisms for automobiles from the early 1900s (“skedaddle wagon,” “skidoodle

wagon,” and “skidoo wagon),” however, more clearly show a direct relationship

between “skidoo” and “skedaddle.”

“Twenty-three” and “skidoo” existed

independently for a few years, without evidence of widespread use of either

one. That all changed in 1905, when both

expressions, often linked together, rocketed to widespread, ubiquitous

use. Contemporary sources attribute the

surge in the popularity to George M. Cohan’s[i]

musical, Little Johnny Jones, the show that introduced the hit

songs, “Give My Regards to Broadway,” and “I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy”.

Twenty-Three

The written record for

“twenty-three,” starts with an interview with the writer, George Ade, published in

October 1899:

“By the way, I have come upon a

new piece of slang within the past two months and it has puzzled me. I first heard it from a big newsboy who had a

‘stand’ on a corner. A small boy with

several papers under his arm had edged up until he was threatening the

territory of another. When the big boy

saw the small one, he went at him in a threatening way and said: ‘Here, here!

Twenty-three! Twenty-three!’ The small boy scowled and talked under his breath,

but he moved away.”

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 22, 1899, page 34.

The date of the interview may be

significant in determining how old the expression was at the time. George Ade was no casual observer of slang; in

1896, he had published the successful book,

Artie, which made prominent use of slang:

The author, Mr. Ade, should

grasp the fact that an abundance of slang does not give the measure of a human

creature, nor, even when it is most adequate to that task, does it make him

necessarily interesting. The hero of

“Artie” is, briefly, a bore.

The New York Tribune, January 3, 1897, page 2.

His book Fables in Slang, released in November of 1899, cemented his

reputation as a connoisseur of slang:

In his latest book, “Fables in

Slang” (H. S. Stone & Co), Mr. Geroge Ade leaves the implications of his

former character-studies and indulges in social satire, some of it pathetically

humorous, some of it bordering closely on coarseness and vulgarity, and all of

it coming near to making the use of slang a fine, even a literary, art.

The Dial, Volume 27, Number 322, November 16, 1899, page 370.

In 1906, “Prof. Frederick Newton

Scott of the chair of rhetoric in the University of Michigan” traced the

origins of “Twenty-Three,” to the end of Charles Dickens’ classic novel, A Tale of Two Cities (just a few

paragraphs before the famous closing line, “It is a far, far better thing I do

than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have

ever known.”):

The last scene in the chapter

depicts the execution of Sidney Carton, the hero of the story. As the line of those condemned to die

advances slowly toward the guillotine, the “knitting women,” keenly interested

in the executions, counts the victims as their heads are shorn off by the fatal

blade. Carton, the twenty-third person

in the line, steps upon the platform the guillotine. Then, says Dickens, “the murmuring of many

voices, the upturning of many faces, the pressing on of many footsteps in the

outskirts of the crowd, so that it swells forward in a mass, like one great

heave of water, all flashes away. Twenty-Three!”

Arizona Republican, June 15, 1906, page 2, column 1.

At first blush, the explanation

sounds ridiculous. A Tale of Two Cities was published in 1859, forty years before “twenty-three” acquired its slang sense. The

opening of a stage version of A Tale of

Two Cities, weeks before George Ade’s interview, however, may throw a

different light on the question. Perhaps

it is not so far-fetched after all.

|

| The Indianapolis Journal, February 1, 1903, part 2, page 8. |

The Only Way, a stage version of A Tale of Two Cities, opened at the Herald Square Theater in New

York City on September 16, 1899 after a successful run in London. Within two months, George Ade reported having,

“come upon a new piece of slang [(twenty-three)] within the past two months. .

. .” Just a coincidence?

|

| New York Tribune, September 12, 1899, page 14. |

An opening-night review of The Only Way suggests that the execution scene was a

prominent feature of the production:

The trial of Charles Darnay

forms the climax of the play, and it closes with the execution of Carton, who

dies for his friend.

The Salt Lake Herald, September 17, 1899, Editorial Section, page

11, column 3.[ii]

A review of the London production

of The Only Way, described the final

scenes; and mentioned the calling of the numbers twice:

The fourth act has three

harrowing scenes and a final tableau. .

. . The third scene is laid in a hall of the Conciergerie, where the numbers of

the victims are called in turn, and whence Carton passes out to his

self-imposed fate hand in hand with Mimi, who instead of being a chance

companion for the guillotine, is brought into earlier acts and is represented

as entertaining a hopeless passion for him.

The final tableau reveals Carton ascending the scaffold in the triumph

of self-sacrifice.

The tableau emphasizes the

significance of the title, since it is a moving picture of “the only way” in

which the hopeless lover, Sidney Carton, can serve Lucie Manette, and it also

enables the actor to repeat the pathetic lines; “It is a far, far better thing

that I do than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than

I have ever known.” Nevertheless, like

much of the expository matter in the play, it is superfluous, since “the only

way” is apparent at the end of the scene in the cell and again when Carton’s

number is called in the hall of the Conciergerie, and the loud, hoarse roar of

the mob is heard from the street.

The New York Tribune, March 3, 1899, page 8.

The gruesome ending of the play was notable, for its time, because it flouted the convention of rewriting stage versions of tragic classics to give audiences a happy ending:

Two of the Rules of the Mangers

Successfully Broken.

A Drama Without Comic Relief or

Happy End.

No matter how serious the

dominating subject of a drama may be, there must be a comic element. That is one rule which American and English

managers seek to enforce upon the playwright.

No matter who deep the sorrows of the hero or heroine, they must

conclude in joy. That is another rule

laid down for authors of theatrical fiction in English. But both are broken by Mr. Wills in “The Only

Way.” He could not well have brought his

version of “A Tale of Two Cities” to any other conclusion for Sydney Carton than the guillotine, but

he might have thrust in some low comedy, and it is a wonder that he got a

London production of the piece without that concession to the ordinary demand

of the theatrical man of business.

. . . The tragedy of Sydney

Carton’s sacrifice is all the more valuable for stage use when given without

breaks in its somberness. It is a

curious fact that “The Ghetto,” after having been played three hundred times in

Amseterdam with a logical climax in the death of the heroine, is brought to an

absurdly happy end, by her rescue from the river, in the translation used at

the Broadway. Well, there was once a

version of “Camille,” in which the consumptive girl regained good health and

became her lover’s wife.

The Sun (New York), October 6, 1899, page 7.

Like the door slamming shut, at the end of Ibsen's, A Doll’s House, twenty years

earlier, the dramatic, somber ending may have made a memorable impact on the

audience. The timing of opening night,

less than two months before the slang expression is first reported, suggests

that there may be an actual connection between “twenty-three” and Sydney

Carton’s beheading. I find it

convincing; you be the judge.

There is at least one slight hitch

in the theory, however; there is at least one report of the slang expression

that pre-dates the New York opening of The

Only Way. But even that account

suggests its origins in A Tale of Two

Cities:

For some time past there has

been going the rounds of the men about town the slang phrase

"Twenty-three." The meaning attached to it is to "move on,"

"get out," "good-bye, glad you are gone," "your

move" and so on. To the initiated it is used with effect in a jocular

manner.

It has only a significance to

local men and is not in vogue elsewhere. Such expressions often obtain a

national use, as instanced by "rats!" "cheese it," etc.,

which were once in use throughout the length and breadth of the land.

Such phrases originated, no one

can say when. It is ventured that this expression originated with Charles

Dickens in the "Tale of two Cities." Though the significance is

distorted from its first use, it may be traced. The phrase "Twenty-three"

is in a sentence in the close of that powerful novel. Sidney Carton, the hero

of the novel, goes to the guillotine in place of Charles Darnay, the husband of

the woman he loves. The time is during the French Revolution, when prisoners

were guillotined by the hundred. The prisoners are beheaded according to their

number. Twenty-two has gone and Sidney Carton answers to -- Twenty-three. His

career is ended and he passes from view.

The Morning

Herald (Lexington, Kentucky), March 17, 1899, page 4 (Barry Popik’s online etymology

dictionary, The

Big Apple).

Had someone from Lexington,

Kentucky been in London recently? Had

someone just read the book? Had someone seen Daniel Frohman's production of an

earlier adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities,

All for Her, starring Mr. and Mrs. Kendal, in 1894? Or is there something else at work

here? There is no shortage of alternate theories.

For his part, George Ade did not claim

to know the origin of the phrase. He

lived in Chicago, however, and may not have been aware of the new play, its

climactic beheading, or its possible influence on the creation of the expression. He detailed two origin stories he had heard:

“I happened to meet a man who

tries to ‘keep on’ on slang, and I asked the meaning of ‘Twenty-three!’ He said it was a signal to clear out, run,

get away. In his opinion it came from

the English race tracks, twenty-three being the limit on the number of horses

allowed to start in one race. This was

his explanation. I don’t know that twenty-three

is the limit. But his theory was that

‘twenty-three means that there was no longer any reason for waiting at the

post. It was a signal to run, a synonym

for the Bowery boy’s ‘On your way!’ Another student of slang said the

expression originated in New Orleans at the time that an attempt was made to

rescue a Mexican embezzler who had been arrested there and was to be taken back

to his own country. Several of his

friends planned to close in upon the officer and prisoner as they were passing

in front of a business block which had a wide corridor running through to

another block. They were to separate the

officer and prisoner and then, when one of them shouted ‘Twenty-three,’ the

crowd was to scatter in all directions and the prisoner was to run back through

the corridor, on the chance that the officer would be too confused to follow

the right man. The plan was tried and it

failed, but ‘twenty-three’ came into local use as meaning ‘Get away, quick!’

and in time it spread to other cities. I

don’t vouch for either of these explanations, but I do know that ‘twenty-three’

is now a part of the slangy boy’s vocabulary.”

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 22, 1899, page 34.

Other common origin stories that

emerged during the period of popularity, after 1905, include telegraphs

operators’ slang, and gamblers’ slang.

The problem with each of those explanations, however, is the lack of

pre-1899 evidence of use. Although there

is some evidence in the record that explain how or why those explanations were

cooked up, there is no evidence of use prior to 1899.

Most of the explanations were offered after

1905, when the expression was widely popular, many years after the expression

was coined. Although those explanations

may accurately describe use prior to 1905, they do not clearly establish use

before 1899. I find the guillotine story

more believable.

Twenty-Three Horses

There are quite a few sources

that refer to horse races that ran with twenty-three horses at the start. To be fair, there are quite a few more

references to horse races with other numbers; but perhaps the frequent

occurrence of twenty-three at least explains why someone might believe that it

could have been the origin of the phrase:

The [Chesterfield] Nursery was

a big prize of one thousand sovereigns, but still we had not expected to see

twenty-three horses at the post for it.

It carried us back to old times, indeed.

Baily’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Volume 43, December 1884,

page 243.

Twenty-three horses started the

“Derby stakes” at Epsom Downs in London, in 1827, 1830, 1831, 1843, 1848, 1850,

1858, 1872, and 1879.[iii] Twenty-three horses started the “Chester Cup”

race in 1859. The Queen of Spain

attended a race in Spain, in 1858; in which twenty-three horses started (she

also witnessed the death of six bulls within a two-hour span the same

day). Twenty-three horses also started

the “Kenner Stakes” in 1897.

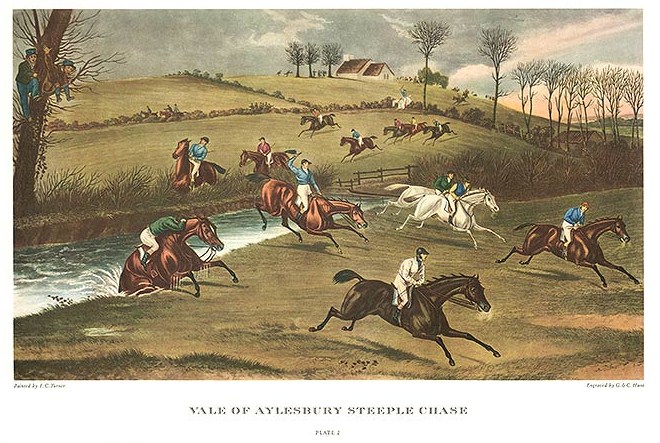

A well-known series of four

prints depicts the Vale of Aylesbury

Steeple Chase, a race that was run in 1836.

An catalogue for an auction held in 1910 describes Plate II of the

series as a, “most pleasing example illustrating this famous steeple chase in

which twenty-three horses and their riders are participating . . . .”[iv]

Although there is some evidence

that some horse races, most notably the Derby at Epsom Downs in London, often

ran with twenty-three horses, other numbers are also common. It is not clear, however, that there was ever

a hard-fast rule that could have spawned the slang expression. Nor is there any explanation for how or why

the expression first emerged among newsboys in Chicago. The role that telegraphers played in

spreading slang, generally, however, may provide some insight.

Telegraph Operators and Slang

How

Slang Travels.

The choicest bit of slang of

the age lay concealed in the ticks of their instruments for years before George

Cohan rescued it and put it to work in one of his musical comedies. Telegraph operators have been saying “23” to

each other over the wire for a number of years; but no one knew anything about

it. A great many people are still

unaware of the fact that this bit of slang originated with telegraph operators;

for only a short while ago a writer ventured the opinion that the term “23” was

of biblical origin, and cited the twenty-third verse of the sixteenth chapter

of Matthew as the probable place.

Evening Star (Washington DC), February 13, 1910, page 16.

Although the story suggests that

telegraph operators used the expression before, “George Cohan rescued it,”

George Cohan did not “rescue it” until Little Johnny Jones opened in late-1904. The expression was already at least five years

old at the time, even if it had not yet become widespread. The article, therefore, is not good evidence

of use before 1899.

An earlier article about

telegraph-operators’ slang, written in 1905, when “twenty-three” was already

popular, suggests that the phrase may not have been as closely associated with

telegraphers as later claimed.

Tellingly, the article makes no reference to “twenty-three” being part

of telegraph-slang, specifically:

“Twenty-three” has almost

passed from slang into proper language, but to the average man “seventy-three”

is still an unknown quantity.

“Seventy-three” is telegraph

slang, and into those two characters are crowded every wish for good. . . . .

It appears on the badge of the Magnetic Club, composed largely of those

in the telegraph and kindred trades, and a huge “73” in electric lights is the

principal decoration at their dinners . . . .”

Evening Star (Washington DC), October 7, 1905, page 12.

But whether or “twenty-three”

originated among telegraphers; telegraph operators may have played a role in

spreading the word:

“People who travel a good bit

are surprised, if they’re observant, at the rapidity with which a new slang

phrase will tour the country,” said a salesman whose district is from the

Atlantic to the Pacific. “I’ve often

left town here with a choice selection of brand new colloquialisms stored up

for use on my western friends, only to have them hurled at me on the other side

of the Rockies when I stepped off the train.

“The telegraph is what does the

trick. Telegraph operators are the great

promulgators of slang. An operator in

New York hears something new and catchy in the line of slang, and he springs it

on an operator in San Francisco. If a

colloquialism is coined in Philadelphia in the afternoon, San Francisco gets it

three hours earlier the same day.

Operators are all the time ‘joshing’ each other over the wire, and slang

is ‘just meat’ for them. That’s how it

attains instantaneous circulation. And

that’s how the ‘wise guy’ of the metropolis gets fooled when he strikes Oshkosh

or Oklahoma expecting to dazzle the natives with something shrewd.” –

Philadelphia Press.

The Paducah Sun, June 27, 1904, page 6.

Any slang spread by telegraph

operators would, presumably, come to the attention of young messenger boys, a

form of human e-mail server, who delivering messages all over town. That might explain how newsboys in Chicago might

use slang from New York City within weeks after it was coined. If you buy the Dickens origin story, it may

not be so surprising that it traveled as quickly as it did. For whatever reason, however, it did not

become very popular, or well-known, until after it was picked up in George M.

Cohan’s, Little Johnny Jones in

late-1904.

Gamblers’

Slang

A couple sources give fairly

detailed descriptions of how “twenty-three” was used as a signal to disperse

during a crooked game of dice or roulette.

The two descriptions are not even remotely similar. They were also made six to ten years after first

use of the expression. It is possible that

the gamblers honestly remembered using the term, “twenty-three,” before it

became wildly popular during and after 1905; but were mistaken in assuming that

it pre-dated first reports of the expression in 1899:

“Twenty-three is an old

gamblers’ expression and I heard it years ago,” said an ex-knight of the green

cloth recently. “In roulette there is a

number 23 and it was always a favorite with pikers. The piker would buy as little as he could and

the number 23 seemed to appeal to him.

He nearly always would play his last white chip upon the number 23 and

then it would be all off with him. The

custom of the pikers was so common that the gamblers took it up and ‘23’ became

a synonym for ‘all in.’”

The Evening Statesman (Walla Walla, Washington), July 5, 1906, page

3.

Why

Twenty-Three Means Down and Out

These spaces marked

“conditional” are used in a great many gambling games, such as spindle; they’re

the most useful thing in the world for leading the sucker on. For when he throws “conditional,” the dealer

tells him that he is in great luck. He has

thrown better than a winning number. He

has only to double his bet, and on the next throw he will get four times the

indicated prize, or if he throws a blank number, the equivalent of his

money. He is kept throwing

“conditionals” until his whole pile is down; and then made to throw twenty-three

– the space which he failed to notice, and which is marked “lose.”

You may ask how the dealer

makes the sucker throw just what he wants.

Simplest thing in the world. The

man is counted out. The table is crowded

with boosters, all jostling and reaching for the box, eager to play. The assistant dealer grabs up the dice, adds

them hurriedly, announces the number that he wants to announce, and sweeps them

back into the box. If the sucker kicks,

a booster reaches over next time the dice are counted, says “my play,” and

musses them up. The player never knows

what he has thrown. I don’t need to say

that “twenty-three,” as slang comes from this game. The circus used it for years before it was

ever heard on Broadway.

Will Irwin, The Confessions of a Con Man, New York, B. W. Huebsch, 1909, pages

84-85.

It seems more likely that the

claim of use, “before it was ever heard Broadway,” refers to the more recent,

better known Little Johnny Jones,

than to the older, more obscure, The Only

Way. It is at least ambiguous on the

issue. In any case, it is possible that

the writer was mistaken about how old the expression actually was. The catch-phrase, “twenty-three,” does not appear

in print (as far as I can tell) between 1899 and 1905. It may have survived within a small circle of

con-men and gamblers, after 1899, and become popular again with Little Johnny Jones. There is no definitive evidence of use prior

to 1899.

Skidoo

“Skidoo” first appears in the

written record a couple years after “Twenty-Three;” as the name of a racing

boat. During the sailboat racing seasons of 1901 through 1904, inclusive, M. St. G. Davies skippered the “Lark” class boat,

“Skidoo,” in a number of races on Long Island Sound. [v] Since the use of the name on a racing boat,

and a fast racing boat, at that, is consistent with the slang sense of leaving

in a hurry, it may reflect that the word was already in limited use.

“Lark” class boats were scows,

with a shallow draft, and no keel.

Although they did not handle as smartly as keeled boats, their shallow

profile made them fast. Their size, and

simple design, made them affordable for young racers. The introduction of “Lark” class boats in the

racing scene sparked some controversy. Several

yacht clubs banned them from participating in their races. It was the old-guard versus the young

Turks. One of the perceived issues seems

to have been their speed:

No sport can flourish that

attempts to discourage the young from entering. . . . You must have young blood, young energy, and

young spirits, to grow and wax strong. . . .

Legislation that tends to keep the young out is thoroughly ill-advised and

bad in every way. Yet that is what some

of our associations are putting on their books. . . . .

Boats like Lark and Swallow

have recruited thousands to the ranks of yachting, the majority of whom never

could have joined except for this type of boat.

Kill this type and you will deal the sport a mortal blow. . . . .

The rule lately adopted by the

Long Island Yacht Racing Association is aimed especially at the scow type, and

to favor the building of expensive craft.

What can you say against these scows?

They are not unsafe. They are not

bad sailers. The only objections seem to

be that they are fast and can and do win races.

The Rudder, Volume 13, Number 5, May, 1902, page 263.

|

| A Lark-class boat sailing on Lake Winnepesaukee (The Rudder, Volume 20, 1908) |

The earliest use of “skidoo,” in

the sense of “leave,” that I could find, is from Martin Green’s humor column, The Man Higher Up, in the New

York Evening World:

“I should think,” suggested the Cigar Store

Man, “that the opponents of Sunday baseball would realize that it is healthy

for the people to get out in the open air and holler.”

“Skiddoo!” said the Man Higher

Up. “Skiddoo!”

The Evening World (New York), April 18 1904, page 10.

The use of the word, without

explanation, may indicate that the word was already known, at least in New York

City. Four of the next five examples of,

“skidoo,” that I could find, all come from the same column. In most cases, the word is used as part of

the expression, “skidoo wagon;” a short-lived euphemism for automobile:

They are doing business to-day

in the same old stands, advertising for suckers in New York and country

newspapers, and the guys that are running them can be seen any pleasant day

shooting skidoo wagons through the park or pushing fast horses on the Speedway.

The Evening World, May 11, 1904, Final Results Edition, page 14.

In the early 1900s, people were

still learning how to live with new technologies that introduced a new element

of danger to the streets. Just as the

introduction of electric trolleys had wreaked havoc a decade earlier (which

gave us the Los

Angeles Dodgers – short for “trolley dodgers”), the automobile brought more

speed, and more danger, into streets that had long been the domain of

pedestrians and slow-moving, horse-drawn wagons (see also my post

on the history of “Jaywalking”). The

use of “skidoo” as a designator for cars reflects that speed:

The

Benzine Buggy and the Tenement Children.

“I see,” said the Cigar Store

Man, “that Commissioner McAdoo is going to police certain east side streets

leading to the ferries, so that automobilists won’t be annoyed by the children

of the poor falling under their machines.”

“Is is all right to protect the

skippers of the skidoo wagons,” replied the Man Higher Up, “but the children of

the east side of New York are entitled to all the consideration that can be

handed out to them. . . . .

“All at once, around the corner

from the avenue, comes an automobile, puffing and snorting and grunting and

horn blowing. It is full of men and

women, who are plainly contemptuous in their attitude. Does the chauffeur slow up to go through that

crowded block of children?

“Not on your speed limit. It is a case of the little ones getting out

of the way. Frantic mothers run out and

grab up their offspring, strong children hustle the weaker to the gutters,

terror-stricken infants fall down and roll in their haste to avoid the puffing

monster. The men and women in the skidoo

wagon ride along with their noses in the air, leaving behind an odor of

gasoline that is distinguishable even in a tenement neighborhood. Is it any wonder that automobiles are not

popular in sections where children swarm, especially when nearly every

neighborhood in town can show a case of a child whose life has been separated

from it by an automobile?

“The automobilists have a

license to run their machines through the streets,” protested the Cigar Store

Man.

“Surest thing you know,” agreed

the Man Higher Up; “but they have no license to run through the people of the

streets.”

The Evening World, May 25, 1904, Final Results Edition, page 14.

When speed limits were

introduced, early enforcement efforts created new problems:

The

Automobile Crop is a Boon to Long Island Farmers.

What’s the use in kicking

against a race concentrated into a few hours, even if the Supervisors have

issued an order that while the skidoo wagons are skiddooing dogs and chickens

must be tied up.

“Look what a good thing the

automobiles have been for the Long Island farmers. Through the long, hot summer months every farmer

within fifty miles of New York pinned a tin star on his red suspenders and

spent his time sitting on a fence and watching for speed violations. They were all constables, and they got half

the fines imposed for running over the law.

The Evening World, October 4, 1904, page 13.

“Skidoo,” was also a verb:

She implanted the salute square

on the muzzle of the ki-yi [(a dog)], whereupon all the male passengers

skiddooed from the car and ran shrieking into a gin mill on the corner. The mutt couldn’t skidoo. The female had him tied.

Evening World, February 7, 1905, Evening Edition, page 10.

Similarities between the sound

and meaning of the words, “skedaddle,” and “skidoo” suggest that they might be

related. Contemporaneous use of,

“skidoodle wagon” and “skedaddle wagon,” as synonyms of “skidoo wagon,” more

strongly suggest a direct connection between the two.

Skidoodle Wagon

In late 1904, the St. Louis

Police Department caught speeders, “scorchers,” with their new-fangled

“Skidoodle Wagon”:[vi]

St.

Louis “Skidoodle” Wagon

The city police in St. Louis,

Mo, have adopted the automobile as a patrol wagon for catching motorists who

violate the speed ordinance. The vehicle

is the product of the St. Louis Motor Carriage Co. of that city and has the

standard 12 h. p. single cylinder motor in it.

It is used to catch fast driving autoists who attempt to escape the

law. It has brass railings, and drop

seat directly in rear of driver’s seat, and facing the rear seat. It is upon this that the offender of the

automobile ordinance must sit and ride to the station when captured by the

“cops.” It is known as the St. Louis “Skidoodle Wagon,” having been so named by

the daily papers of that city.

Automobile Review, Volume 27, Number 11, December 31, 1904, page

626.

|

| The St. Louis Republic, October 25, 1905, page 1. |

The introduction of the police cruiser

was apparently one step ahead of speeding tickets. When speeders were caught, they did not

receive simple tickets; they were arrested and taken down to the police

station:

Unmindful of the presence of

the police “skidoodle wagon,” two North Side automobilists took liberties with

the speed ordinance last evening and were placed under arrest as a result. They will appear before Judge Pollard this

morning. . . . [The policeman] took up the chase, but did not attract any

special attention, as he says his machine was not fully extended. He allowed the two men to go as far as

Jefferson and St. Louis avenues, where he moved up between them and ordered the

chauffeurs to stop. Both were placed

under arrest and taken to the Sixth District Police Station, where they were

released on bond.

The St. Louis Republic, August 16, 1905, page 5, column 1.

Henry C. Garneu and Thomas W.

Crouch Jr. Pay $3.

They were arrested while

“scorching” in an automobile in Forest Park Saturday evening. They were caught

by Policemen Cooney and Stinger in the police “skidoodle wagon” after a chase.

The St. Louis Republic, April 4, 1905, page 1, column 3.

The new police car was not the

first “skidoodle wagon” in St. Louis. Visitors

to the St. Louis Fair were exposed to the term in mid-1904:

ST.

LOUIS AN AUTO MECCA.

Thousands of motor carriages to be Here for

Day at Fair August 11.

St. Louisward thousands of

automobiles will wend their ways, beginning to-day.

From all points of the compass

will come the red, green, yellow, white and other colored “skidoodle wagons.” They will come singly and in clubs to

participate in the ceremonies of St. Louis Day at the Fair, August 11.

They will assemble across the

river, and, forming there, they will speed in stately formation across the big

bridge and into the World’s Fair grounds.

The phalanx will be the greatest procession of the Twentieth-Century

carriages since the automobile has become a fact.

The St. Louis Republic, July 25, 1904, page 6, column 6.

An article in a Minnesota

newspaper, about an exhibit of early steam engines at the St. Louis World’s Fair,

compared Nathan Read’s

steam-powered wagon, built in 1789, to modern “skedaddle wagons”:

Wood was fed into the furnace

from the rear of the machine and the driver sat just in front of the steam box,

while the goods with which he loaded the steam wagon’s receptacle for

transporting loads was directly in front of him and extended some 12 or 14 feet

in length by about 10 feet in width. This

feature of the exhibit attracts a great deal of notice and by many is

characterized as the original attempt to produce the “skedaddle wagon” of the

present day.

Saint Paul Globe, November 27, 1904, page 5, column 6.

In Salem, Oregon, someone who

either liked lawn care, or disliked driving, compared the thrill of mowing the

lawn to driving a “ski-doodle wagon”:

A Salem man says there is

almost as much excitement in being the chauffeur of a lawn mower as a

ski-doodle wagon.

Daily Capital Journal, August 2, 1905, Last Edition, page 5, column

2.

By the end of the year, the

ubiquitous and ridiculously popular, “twenty-three for you, skidoo!” seems to

have entirely eclipsed “skidoo wagon,” “skidoodle wagon,” and “skedaddle

wagon.” I could not find any examples of “skedaddle wagon” after 1905, and only one example of “skidoodle wagon,” and a few

instances of “skidoo wagon” extending into the 1910s.

|

| Motor Talk, Volume 3, No. 1, January 1907, page 20. |

Twenty-Three, Skidoo!

“Twenty-three” and “skidoo”

coexisted for several years before they were inextricably combined in about

1905. During the early years, George M.

Cohan’s musical, Little Johnny Jones

generally received credit for popularizing the two expressions, and their

combination.

George M. Cohan’s Little Johnny Jones introduced the world

to “I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and “Give My Regards to Broadway.” James Cagney’s famous dance number, from the

movie “Yankee Doodle

Dandy,” depicts George M. Cohan’s performance in Little Johnny Jones.

Little Johnny Jones made its debut at the Liberty Theatre in New

York City on November 7, 1904. When the much

anticipated show finally reached Los Angeles in April, 1906, “23” and “skidoo”

made a big impression:

Cohan’s Musical Comedy is

Californian to the Core and is a Winner – And Such a Chorus!

The much belated but better

late than never “Little Johnny Jones “ has arrived. He has been arriving so long and at so many

different hopurs that Los Angelans had almost become skeptical but last night

he demonstrated he really exists and is surprisingly active little mortal.

The entire Johnny Jones company

came with him to the Mason, and it is a large one. There appear to be chorus girls without

number and of every variety imaginable.

At times it would almost appear that the chorus girls have to work

overtime and many of the most beautiful effects are produced by their costumes.

The piece is musical and the

scenic effects are far more striking than any which have been seen here this

season.

The third act in which the

scene is laid in Chinatown, San Francisco, is especially spectacular, and the

costume effects all that could be desired.

There are few new jokes but “Little

Johnny Jones” does not depend on joes for its popularity.

The

Bright Ones

Tom Lewis [(who appeared in the

original New York Production)] as The Unknown [(a detective)] is responsible

for most of the good ones and his “23,” “skidoo” and a few others never failed

to bring forth the intended laughs.

Los Angeles Herald, April 5, 1906, page 3.

The expressions caught on quickly

with local theatrical agent, Len Behymer:

Len

Behymer’s “Skiddoo”

. . . Mr. Behymer has been

quoting “Little Johnny Jones” for several days, and anyone who has chanced to

meet him will recall “23 for you,” “skidoo” or some similar phrase.

Los Angeles Herald, April 15, 1906.

The positive response the phrases

engendered in Los Angeles may mirror their effects on audiences elsewhere. As early as February, 1906, newspaper accounts

in other cities had already made the association between the show, and

“twenty-three” and “skidoo.” For their

part, however, neither Cohan nor Tom Lewis took credit for creating the terms. Cohan said he first heard the word in San

Francisco, and Lewis believed it was gamblers’ code:

For the past six months those

who indulge in up-to-date slang have been saying “twenty-three.” The meaning of the expression has been too

obvious from its use to require a definition – it is the equivalent and the

successor of “get thee hence,” “go ‘long,” “on your way,” “skidoo,” and other

methods of conveying the impression that the party of the first part desires

the immediate departure from his presence of the party of the second part. . .

.

The play that gave

“twenty-three” wide-spread popularity is now in Minneapolis, “Little Johnny

Jones,” and its author, Cohan, says he doesn’t know where it came from, except

that he heard it in San Francisco.

Tom Lewis who plays the

detective and says: “twenty-three for you,” however, has a theory that seems

reasonable.

“It was originally a gambling

term,” he says, “used in connection with a dice game, worked by grafters

connected with the circus. Twenty-three

was the throw of the dice that got the money, and when it was called it was

also a signal for the cappers to get out of the way quick before the victim

made a roar to get his money back. It

would be used with variations sometimes such as ‘eighteen and five,’ ‘eleven

and twelve.’ The cappers would do a little

mental arithmetic and then hike for the tall timber.”

The Minneapolis Journal, February 13, 1906, Page 11.

Despite their denials, several

more articles published in 1906 continued giving them credit. Five years later, the San Francisco Call (November 21, 1909, page 27) reported that,

“’Skidoo’ and ‘Twenty-three’ are Cohan expressions.” We know, however, that such

an attribution is overstated, as “twenty-three” and “skidoo” both pre-dated Little Johnny Jones. But what role did the play play in

popularizing the two expressions?

Little Johnny Jones

Little Johnny Jones is a story about an American jockey whose

reputation is tarnished by allegations of throwing a race in England. It was a lie, of course, and a detective gets

the good on the bad guys. The detective

speaks the line, “twenty-three,” several times in the play, and the word,

“skidoo,” once; but does not put the two words together.

In one scene, the detective is

trying to get rid of an annoying waiter, in what may be an early precursor of

Abbot and Costello’s “Who’s on First” gag:

Waiter. I have a cup of tea here, sir.

Wilson. Well, go ahead and drink it, don't let me stop you.

Waiter. Thank you, sir.

Wilson. Twenty-three.

Waiter. What sir?

Wilson. Twenty-three.

Waiter. Who, sir?

Wilson. You.

Waiter. No sir, thirty-six. Is there anything else I can do, sir?

Wilson. If there was you wouldn't be a waiter. (Waiter turns and

exits into door L.)

Transcript of a script of Little Johnny Jones available at: Doug

Reside, The New York Public Library Blog,

Musical of the Month: Little Johnny Jones.

|

| Tom Lewis (left), in Little Johnny Jones |

Towards the end of the show, the

detective rehabilitates Johnny Jones’ reputation, and tries to get rid of one

of the bad guys; McGee:

I am tickled to death to see

you with this man - McGee. (At mention of his name McGee turns and swells up.)

He's a good man - I know him. He's a Brooklyn Elk. You don't want to overlook

this jockey Jones. They may have fixed that horse in England but they couldn't

fix the jockey. He's the candy all right. I don't blame your niece for getting sweet

on him. (At this McGee strolls down stage.) but this man with the gray looks.

He's no good, arouse mit him. I'm going

to get him to sign this, the skedew.

I want to give you a little bit of advice.

Transcript of a script of Little Johnny Jones available at: Doug

Reside, The New York Public Library Blog,

Musical of the Month: Little Johnny Jones.

|

| Tom Lewis (left), in Little Johnny Jones |

The use of “arouse mit him,” is

apparently an Anglicized version of the German phrase, “’raus mit ihm,” meaning

“out with him. The meaning of the German

expression reinforces the meaning of the word, “skewdew” (apparently an

alternate spelling, or possible transcription error, of “skidoo”). “’Raus mit ihm” would not have been as

esoteric in 1904 as it may be today. A

song entitled “’Raus mit ihm,” had been a hit in 1899

and the country was filled with many more, recent German-speaking immigrants at

the time.

Little Johnny Jones may have popularized the two expressions,

separately, and been mistakenly credited with the combination. The script (as published and transcribed)

does not appear to be the source of the combination. Several sources credit the actor, Tom Lewis,

by name. It is possible that h ad-libbed

the line; got a big laugh; and continued using the expression, despite

different dialogue in the script. It

is also possible that the two expressions became popular separately, but were

combined by the public, naturally, based on similar meanings and usage.

In November 1905, however, a

newspaper in Oklahoma, credited a different vaudeville act, the Roger Bros.,

for the expression, “It’s Twenty-three for yours!”:

“Its Twenty-Three For Yours!”

Roger Bros.’ Famous French

Slang Phrase in Police Court.

The Guthrie Daily Leader (Guthrie, Oklahoma), November 11, 1905,

page 1.

The Rogers Brothers were well

known vaudeville performers who had been around since at least 1890. For many years, they performed as “German

comedians,” known for their “Teutonic witicisms.” In 1898, however, they became headliners;

first in The Reign of Error,[vii]

and then in a series of shows set in different locations – the titles sound a

bit like Hope/Crosby road pictures: The

Rogers Brothers in Wall Street (1899); The

Rogers Brothers in Central Park (1900); The

Rogers Brothers in Washington (1901), The

Rogers Brothers in Harvard (1902), The

Rogers Brothers in London (1903), The

Rogers Brothers in Paris (1904), and The

Rogers Brothers in Ireland (1905).

|

| Gus and Max Rogers in, The Rogers Brothers in Paris, Der Deutsche Correspondent (Baltimore Maryland), February 12, 1905, page 5. |

The show, The Rogers Brothers in

Paris, from 1904, may explain the Oklahoma headline’s reference to “twenty-three”

being a, “French Slang Phrase,” in 1905.

But although searches for the phrase, “Rogers Brothers,” yields hundreds

of hits between 1898 and 1906, only this one article, credits

them with popularizing the phrase. They

may have started using the phrase after it was used in Little Johnny Jones; or, their use may simply reflect the same

awareness of the phrase that led to its being used in Little Johnny Jones as well. Their use of the phrase at least illustrates how

popular the phrase had become by late 1905.

Twenty-Three, Skidoo!

As noted earlier, “twenty-three” first

appeared in 1899, but does not appear in print again, to my knowledge, until about

six years later; nearly a year after Little

Johnny Jones debuted. In the

earliest example that I could find, it appears along with, “skidoo,” but not in

the familiar, “twenty-three; skidoo!” format.

The context suggests that both expressions had already reached a high

level of familiarity. They appear in a “humorous”

story about a relentless, traveling, encyclopedia salesman. Each negative response by the customer

triggers the salesman to tout a corresponding selling point:

“Get out!” roared the man. “Didn’t I tell you that I ain’t in no need of

that book?”

“From your language, sir, I

infer that you are. It contains a

chapter on the correct use of the English language, rules of etiquette ---“

Skiddoo! Git! Twenty-three for

yours!” howled the victim.

“It also contains an up-to-date

slang dictionary and ---“

“Say,” roared the man, “will

you get out of here, or will I have to throw you out?”

“--- also contains a jiu jitsu

treatise, an easy way of getting rid of objectionable persons like myself, and

it also ---“

“I’ll take it then,” he said,

sinking meekly into his chair, “and as soon as I learn that jiu jitsu I pity

you or any book agent that comes around and tries to sell me gold bricks! How

much?” – New York Sun.

Dakota Farmers’ Leader

(Canton, South Dakota), August 18, 1905, page 6, column 3.

Many other early examples are

phrased, “twenty-three for you (or mine/or yours);” often followed immediately

by “skidoo.”

Twenty-three for mine – skidoo!

Evening Star, September 23, 1905, page 2.

In St. Louis, home of the

“skidoodle wagon,” you could purchase twenty-three “Ski-doo” Fruit Wafers for a

dime:

Twenty-three for You. The Candy

Man has something entirely new for you in his Ski-doo Fruit Wafers, and even 23

won’t be enough for you – yes, 23 for only 10c.

St. Louis Republic (Missouri), November 5, 1905, page 25.

Twenty-three for his! Skidoo.

Goodwin’s Weekly (Salt Lake City, Utah), January 6, 1906, page 6.

When freshmen at the University

of Illinois beat the sophomores in some inter-class competition, they gloated:

Have

a look! Have a look!

Ye conquered sophomores!

Now

that you have met defeat

Yours

heads are hanging toward your feet.

But

if your head you chance to raise

A

victorious Freshman meets your gaze.

You

are lobsters every one!

The

biggest dubs beneath the sun.

Poor

chesty sophs, you failed to shine.

23!

Skidoo! Poo Poo for you. ’09.

The Daily Illini, November 9, 1905, page 1.

|

| New York Clipper, Volume 54, Number 7, April 7, 1906, page 190. |

|

| New York Clipper, Volume 54, Number 7, April 7, 1906, page 202. |

Imposing Shakespearean actor, the

original Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and “dean of the American stage,” Richard Mansfield,

even got in on the act with, “Skidoo, 23”:

“Hoot Mon”

Mr. Richard Mansfield, who has

been accounted “as mild a mannered man as ever scuttled ship or cut a throat,”

is out with a protest against his growing reputation as a self-centered cynic. Mr. Mansfield declares this reputation does

him a great injustice, that he is really tame and will eat out of the hand,

jump thru hoops and count up to nine at command. . . .

The dean of the American stage

does admit having been irritated once.

It was when he was doing the dying scene in one of his plays. The house was still and nobody dropped a pin,

but suddenly an athletic scene shifter let off a sneeze that shook the stage

and made the footlights twitter. The

scene was ruined. Mansfield felt the

humiliation of the affair, but even then he refrained from bloodshed. Stepping to the edge of the scene, he

murmured: “Skidoo, 23,” and on such a slight foundation has Mr. Mansfield’s reputation

as a terror been constructed.

The Minneapolis Journal, March 11, 1906, part 2 (Editorial), page

4.

The familiar form, “Twenty-three

- Skidoo!” first appears in 1906. Barry

Popik, renowned word sleuth and proprietor of the online etymology dictionary, The

Big Apple, uncovered the earliest known example of the now familiar form. In April, 1906, Billy B. Van performed

the song, “Twenty-three -- Skiddoo!” one

of the, “two best songs of the spring season,” in The Errand Boy:

New York Clipper, Volume 4, Number 9, April 21, 1906, page 258.

Soon, the expression was

everywhere:

|

| The Evening World (New York), May 4, 1906, page 3. |

|

| New York Tribune, July 29, 1906, page 38. |

Of

Course.

Gunner – I see where a man in

the southwest had twenty-three children and then disappeared. What do you think of that?

Guyer – Why, that was nothing

unusual.

Gunner – What?

Guyer – Why, twenty-three –

skidoo!

The Plymouth Tribune (Plymouth, Indiana), November 15, 1906, page

6.

23, skidoo, for you, do you

mind?

Dakota Farmers’ Leader (Canton, South Dakota), June 22, 1906, page

4.

“Mary” had her little lamb, all

right, in the shape of a huge toy production on wheels, which “she” pulled

after “her” with a string; and on the lamb appeared the mystic legend “23 – skidoo!”

This vision moved many of the spectators to tears. It would have melted the heart of a stone

dog.

Goodwin’s Weekly (Salt Lake, City), July 21, 1906, page 10.

“23 – Skiddoo” sale at “The Hub”

is a winner for you.

Arizona Republican (Phoenix), August 10, 1906, page 4.

|

| Arizona Republican, August 15, 1906, page 6. |

“23” and “Skiddoo” hit the “big screen”

together (how big were movie screens big then?) in June of 1906; in a film that

hearkens back to the days of the “skidoo wagons” racing through Central Park:

“23” Or The Brief Experience of

the Skiddoo Bros. in Society.

This new and humorous film will

be appreciated by everyone who has laughed at the predicaments of the famous

hall room boys. It shows how they called

on the Astorbilt Sisters and how they went for an automobile ride in Central

Park. Is beautiful in photography, and a

laugh from start to finish.

The New York Clipper, Volume 54, Number 16, June 9, 1906, page 450.

|

| New York Clipper, Volume 54, Number 16, June 9, 1906, page 450. |

But nothing lasts forever. In 1916, one writer wondered:

What’s become of “Twenty-three:

Skidoo!”

The Day Book (Chicago, Illinois), June 27, 1916, last edition, page

12.

What became of “Twenty-three: Skidoo?”

I guess it, “twenty-three,

skidooed.”

|

| The Minneapolis Journal, December 23, 1906, Part II, page 1. |

[i]

George M. Cohan may also have had a connection to the origin of another iconic

word; “Bozo.” The play that seems to

have introduced the word, “Bozo,” was the sequel to a George M. Cohan play. See my post, What

Came First, Bozo or Bozo?

[ii]

Another reviewer reported that “’The Only Way’ has three powerful climaxes. . .

.” The Times (Washington DC),

September 24, 1899, second part, page 17.

Presumably Carton’s beheading was one of those climaxes.

[iii]

Louis Henry Curzon, The Blue Ribbon of

the Turf: a Chronicle of the Race for the Derby, Philadelphia, Gebbie,

1890.

[iv] Rare and Valuable Books and Colored Sporting

Prints, Including Selections from the Library of George G. Tillotson of

Wilkes-Barre, Pa. to be sold February 1 and 2, 1910, New York, Anderson

Auction Co., No. 805, 1910.

[v] See,

e.g., A. F. Aldridge, The Yachting Record: Summaries of All Races

Sailed on New York Harbor, Long Island Sound and Off Newport in 1901, New

York, Thomson and Company, page 16 (Indian Harbor Yacht Club, Spring Race,

Thursday, May 30, 1901); New York Tribune,

June 14, 1902, page 4 (New-Rochelle Club Regatta); The Sun, June 14, 1903, page 8 (Larchmont Spring Regatta; “The

Skidoo won the race for the Larks.”); Motoring

and Boating, Volume 1, Number 11, June 15, 1904, page 336 (Manhasset Bay

Regatta).

[vi]

The word, “skidoodle wagon,” echoes an earlier use of the word, “doodle-doodle

wagon,” for the vehicle that takes crazy people to the insane asylum: “Adams,

ye’er nutty, an’ I’m sorry for ye’er family this minute. I should be callin’ the doole-doodle wagon,

instead of standin’ here gossipin’ wid ye, an’ listenin’ to ye’er insane

maunderin’s as if ye had the power of consicutive thought. There was no snow in Gar-r-field Par-rk this

mornin’.” The Saint Paul Globe

(Minnesota), September 16, 1900, page 5.

This was the only use of, “doodle-doodle wagon,” that I could find, so I

cannot say whether it was a common expression or a one-off, or whether it could

have had any influence on the later development of “skidoodle wagon.”

[vii] The

title of the Rogers Brothers first successful show as headliners gave me some

pause. The Reign of Error appears to be a play on the expression, “reign of terror,” used

to denote the period of violence following the French Revolution; the period of

time during which A Tale of Two Cities

is set. Might they have originated the

phrase in a parody of A Tale of Two

Cities, even before The Only Way

premiered? The Reign of Error, however, was not a parody of A Tale of Two Cities; it was about the

adventures of a troupe of European performers on a road-trip to Brazil. The connection appears to be merely

coincidental.

I encountered an interesting 1906-published variant of linking 23 with Skidoo. In the final row of 'Nibsy the Newsboy' for the 20th of May, 1906, Nibsy rolls a barrel at some pursers while saying, ``Skidoo an' 46, double quick, fer nine''. It's reprinted at https://www.gocomics.com/origins-of-the-sunday-comics/2021/02/24

ReplyDeleteI assume the ``double quick'' justifies the doubling of 23 to 46. It's a neat variant.

Well that is interesting; something I hadn't run across before. Opens up a whole new field of Skidoo study. Following your lead, I found a few dozen references along those same lines. When Oklahoma was to be the 46th State, one writer called it the "Double Skidoo" state. When a basketball team scored 23 in each half, its score was called a "Double Skidoo." A few advertisements offered "double skidoo" pricing, setting prices for some items at $0.23, and larger items at $0.46.

Delete\I remember reading a transcript of the logbook of the Slop-of-War USS Richmond from about 1864, while she was blockading the southern Mississippi River during the Civil War. When a troop of Confederate cavalry was suddenly seen on the riverbank, the Richmond opened fire, causing the officer on deck to note in the formal logbook "...and they skedaddled away right fast", a rather serious place to find such informal slang!

ReplyDelete