In February 2023, an international incident involving a surveillance balloon from China prompted some anonymous twitter user to post this meme of a Chinese take-out box suspended by a balloon.

The image plays off the origin of the surveillance balloon in Communist China. But the familiar take-out containers are not from China, Communist or not.

According to Peter Kim, executive director of New York’s Museum of Food and Drink, the box is a “uniquely American Design” and “as American as Apple Pie.”i He agreed with The New York Times Magazine, who had traced the origins of the box to Frederick Weeks Wilcox, of Chicago. Wilcox received a patent for a “Paper Pail” in 1894 (US529053, November 13, 1894).ii

Coincidentally, however, at about the same time the Chinese balloon incident was playing out in the news media, I ran across earlier references to what looked like “Chinese” take-out-style containers from 1882 and 1884.iii I ran across the references while researching the history of ice cream scoopsiv - the paper containers being suited (according to their designers) for packing ice cream. Seeing the meme at about the same time prompted me to dig deeper. A quick search convinced me that I had stumbled across new information. As I dug deeper, a more interesting story unfolded.

The history of “Chinese” take-out box is even more “American” than previously known. It has connections to early American history, as it was invented by a long-serving Vice President of Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute, and was patented just in time for the United States’ Centennial in 1876. The story has drama, in-fighting, backstabbing, litigation and corporate squabbles. And it is wide-ranging, touching on the history of other well-known, everyday objects - the stapler, paper cups and motion pictures.

Folded paper boxes made of a single sheet of paper are old. A patent issued in 1874, for example, described boxes “made complete from one piece of material by several folds” as “very old.”v What was new and radical about about the style of box that would later be associated with Chinese take-out was that the arrangement of folds made it basically water-tight, with no seams in the storage compartment where something might leak out.

The earliest patent that embodies the general look and characteristics of the modern take-out box was issued on March 28, 1876 - just in time for the Centennial. The inventor was a man named Henry Renno Heyl, from Philadelphia.

Heyl also invented the single fastener on either side where a handle might be secured.

I prefer to so proportion the folds and lap them at the sides that a single fastening at each side will serve to secure the folds themselves and a handle or ribbon or other material.

Other than describing the box as “water tight,” Heyl’s original patent did not limit the types of things that might be carried in it, although it did mention its suitability “ice cream, fruit, and most commodities for which the box is specially intended.” Later patents for similar boxes listed things like, “ice cream, oysters, and like substances of semi-fluid character,”vi “berries, oysters, ice-cream, and the like.”vii Paper pails along these lines would eventually be generically referred to as “oyster pails,” regardless of use.

As recognizable as Heyl’s paper box design has become, it is only one of several innovations he had a hand in, and it may not be the most widely known or most important of his accomplishments. Heyl invented the stapler, was president of one of the earliest paper cup companies, and staged the first-ever exhibition of a motion picture.

Henry R. Heyl, of Philadelphia, for many years vice-president of the Franklin Institute, and an inventor of note, was at the Strand on Sunday. Mr. Heyl is the inventor of wire stitching [(staplers)], the first folding box and lately of the paper milk bottle. . . . The Union Paper Cup Co., of Trenton, of which Henry R. Heyl is president, are building a plant at Fernwod, near Trenton . . . .

Five Mile Beach Weekly Journal (Wildwood, New Jersey), September 12, 1906, page 1.

The first moving pictures ever exhibited in public. They were made by Henry Heyl and were projected on a screen before 1,600 people in Philadelphia in 1870.

Scientific American, Volume 112, Number 23, June 5, 1915, page 530.

Henry Heyl is frequently credited as the inventor of the modern staple. He did not invent the first staple, but he did invent the first stapler that could insert and bend the staple in one shot. His design was not perfect, he used a second stamping action to better secure the staple, but it was a major innovation and generally considered to be the first “single shot staple” machine.viii

Devices for Inserting Metallic Staples, US195603, September 25, 1877.

Heyl’s one-shot stapler was not unrelated to his paper box. It may have been developed as a solution to problems associated with paper box making and book binding. Heyl had a succession of patents, involving the use of staples, many of those with a co-inventor named August Brehmer. Their earliest such patent, from 1872, was for an “Improvement in Machines for Making Boxes of Paper.” Their early stapling processes used two steps - insert the staple and then crimp them. Later patents described the use of such staples to make boxes and in the binding of pamphlets and books.

Heyl’s and Brehmer’s designs won at least two awards. They were honored at the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 (the Philadelphia World’s Fair). The Novelty Paper Box Company (the assignee of most of their patents) received an award for their “wire stitching machines machines for books and pamphlets” (“wire stitching” in this context refers to stapling).ix In 1882, the Franklin Institute awarded their “Scott legacy medal and premium of twenty dollars” to Henry R. Heyl and Hugo Brehmer for their “Book Sewing Machine.”x

Heyl’s newly patented “paper box” may have been one of the first commercial uses for his newly patented stapling processes. His paper box patent describes the use of staples to secure the folds and attach the handle.

I prefer . . . to fold these laps outside and around two opposite sides of the box, so that the two pairs of laps, together with the two ends of the handle of ribbon or tape, may be secured by a single staple-fastening at each side . . . .

These staples are readily made and applied by the improved machine described in another application for Letters Patent which I have executed of even date herewith.

“Paper Box,” US175456, March 28, 1876, filed July 30, 1875.

Heyl did not invent the paper cup, but “was the inventor of the machines which make paper cups.”xi In 1906 he served as President of the Union Paper Cup Company of Trenton, New Jersey. That year is interesting because it is two years earlier than the earliest patents issued to Lawrence Luellen, who is generally given credit for inventing the paper cup in 1908.

The Union Paper Cup Company had connections to a man named James C. Kimsey, from Philadelphia, whose paper cup patents pre-date Luellen’s by several years. Kimsey’s main interest was in making paper milk bottles for sanitary delivery of milk, but he also developed paper cups. A man named John J. Shea held paper cup patents which were even earlier than Kimsey’s; and Shea’s cups were available for sale several years before Luellen filed his first patent application.

Luellen’s designs and and his company’s business model won the day. The company he and his partners founded would later become the Dixie Cup Company, the dominant player in the market, but he did not “invent” the paper cup as frequently claimed.xii

And in another first, Henry R. Heyl of Philadelphia was the first person to project moving images of people onto a screen - the first “motion picture,” in an exhibition of the “phasmatrope” at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia on February 5, 1870.

The brilliant conception was due to the ingenuity and photographic skill of Henry R. Heyl, of that city. The exhibition was repeated by him before the Franklin Institute March 16th following. These were the first exhibitions known to the writer of photographs to represent in motion living subjects projected by a lantern upon a screen.

C. Francis Jenkins, Animated Pictures, an Exposition of the Historical Development of Chronophotography, Washington DC, 1898, page 7.

The photographs were staged poses, not taken from people in motion. They represented six sequential positions of dancing couple waltzing. The six were repeated three times to fill in eighteen frames on the wheel. The wheel repeated the same sequence of motion over and over as it was turned, so it was limited to showing brief, repetitive motions. An operator controlled the machine by hand, and synchronized with a live orchestra, the images waltzed on the screen in time with the music - the first “motion picture.” He is said to have been one of the dancers who posed for the images.xiii

As for Heyl’s paper box, now associated with Chinese take-out, it would remain basically the same for a century and a half. But Heyl’s company did not last that long. Heyl and Brehmer assigned their paper box and stapler patents to the Novelty Paper Box Company. Heyl’s “oyster pail” was not their only product, but it may have been one of their most valuable. The Novelty Paper Box Company went out of business in 1894, just after his paper box patent expired (at the time, patents were valid for seventeen years). Other patents were also expiring around the same time and earlier, so it may have been a cumulative loss of competitive advantage, without commensurate investment in innovation to maintain their competitive advantage.

The reason for the dissolution of the company was given as “the existing conditions of trade, and particularly the competition affecting the business of the company.” The corporation had valuable patents, which have just expired.

Philadelphia Times, March 25, 1894, page 3.

When Heyl died suddenly in 1919, due to injuries sustained in a streetcar accident, he was remembered as the inventor of the paper oyster pail. His name was still associated with at least one style of pail.

A mechanical engineer by profession, Mr. Heyl specialized in the design of special machinery, making articles constructed of paper, and wire. He was the inventor of the first machine for the making of wire stitched boxes and paper oyster pails, one design of which still bears his name.

Reading Times (Reading, Pennsylvania), March 21, 1919, page 3.

It is unclear whether his name was used as a trademark of the Kinnard Manufacturing Company, or as a generic term for a particular style. Oyster pails had been available under the name since at least 1894.

|

The Merchant’s Journal (Topeka, Kansas), December 29, 1894, page 19. |

|

The Inland Printer, Volume 24, Number 1, October 1899, page 158. |

|

The Dayton Herald (Dayton, Ohio), October 14, 1899, page 10. |

Following in the footsteps of Heyl's first paper oyster pail, other inventors and manufacturers would improve upon the product, creating the competition that would eventually drive Heyl's Novelty Paper Box Company out of business. Numerous designers and inventors would make technical changes, modifications and alterations over the years. Frederick Wilcox, for example, created a design in which the wire bail (or handle) did not poke through the interior wall of the container. His patent was at least the 25th improvement or modification to the paper oyster pail in the eighteen years following Heyl’s patent.

Wilcox’s “paper pail” was only one small part of his long career in paper products.

Frederick W. Wilcox, a New York manufacturer and inventor of paper boxes, has died at St. Luke’s Hospital, in that city, of apoplexy and heart trouble. For nearly forty years he was identified with the J. W. Wilcox Paper Box Company,xiv and was interested with his father in the inventions of the ice cream box, so generally used by confectioners, the congress tie envelope for legal papers, the paper oyster pail and many other paper box inventions. He was widely known in the tea and coffee trade through his extensive trade in sample boxes. He was fifty-seven years old.

Boston Evening Transcript, January 22, 1909, page 5.

The paper “oyster pail” seems to have been a profitable product, suggested by, if nothing else, the interest in innovation as evidenced by the large number of patents issued in the field. And some of those patents were considered valuable, sparking infringement litigation among the various players. Some of the inventors went from partners to competitors and opposing parties in paper box patent litigation, while others simply jumped ship from one company to the other.

Interestingly, most of the folded “oyster pail” patents between Heyl’s original patent in 1876 and Wilcox’s patent in 1894 were issued to inventors from Dayton, Ohio.xv Dayton was the home of the Wright Brothers and styles itself the “City of Inventors.” It was also the home to Aulabaugh, Crume & Company, later Crume & Sefton Manufacturing, later Carter-Crume Company, which later became the Kinnard Manufacturing Company. Aulabaugh, Crume, Sefton and Kinnard all held patents in paper “oyster pails” at one time or another, as did several of their employees.

Coming one year after Heyl’s patent, Peter M. Aulabaugh 1877 design looks a bit different, with curved sides, but it is the earliest patent to disclose the wire bail still in use today.

Improvement in Paper Vessels, US198332, December 18, 1877, Peter M. Aulabaugh, assignor to Aulabaugh, Crume & Co.

James A. Weed’s 1880 design introduced, for the first time, the angular wire bail, bent into angles, as opposed to curved over the top as in a classic bucket. A later patent, to Theodor H. Huewe (US262951, August 22, 1882), explained that the rectangular bail was functional; “I preferably make [the bail] of wire and of rectangular form, so that the weight of the vessel and its contents shall not tend to draw the sides together when the vessel is carried by the bail.”

An 1884 patent that looks very much like a modern take-out box, was the brainchild of two of the most important people in Chinese take-out box history, William E. Crume and Joseph W. Sefton, both of Dayton, Ohio. Crume and Peter Aulabaugh were at one time partners in Aulabaugh, Crume & Co. of Dayton, the assignee of Aulabaugh’s earlier paper vessel patent. The two had also been co-inventors on a patented “paper dish,” designed for grocers selling small quantities of bulk butter, lard or the like.xvi

Sefton and Crume had a falling out at one point, and Sefton moved to Anderson, Indiana, another minor hotbed of folded box patents. At least six early folded paper box patents were issued to inventors from Anderson, Indiana, or assigned to Sefton’s company in Anderson.xvii

As early as 1882, Crume and Sefton were partners in the Crume & Sefton Manufacturing Company, of Dayton, makers of various paper products. But several years later, Crume and Sefton went their separate ways - Crume continuing to run Crume & Sefton in Dayton, and Sefton running his own company in Indiana. The split resulted in litigation and an injunction. And both men later filed patents in their own, individual names, assigned to their own rival companies.

Paper Vessel, US303216, August 5, 1884, William E. Crume and Joseph W. Sefton, assignors to the Crume & Sefton Manufacturing Company.

Dayton Herald, August 19, 1882, page 4.

Reorganization

At a reorganization of the Crume & Sefton Manufacturing Company this morning the following directors were selected;

President - W. E. Crume . . . Board of Directors - W. E. Crume [and three others, not including Sefton)].

The Dayton Herald, May 17, 1888, page 2.

Yesterday the reorganization of the Crume & Sefton Manufacturing Company was noted in the Herald. To-day it was learned that Mr. J. W. Sefton, retiring president, has sold his interests in the company and has temporarily retired from active business.

The Dayton Herald, May 18, 1888, page 3.

NOTICE.

Dayton, Ohio, June 29, 1889.

The J. W. Sefton Manufacturing Company recently started into business at Anderson, Indiana, and engaged in imitating some lines of our goods and infringing our trade marks. We at once began a suit in the U. S. Court, at Indianapolis, for an injunction against such infringement and for damages. . . . Respectfully, The Crume & Sefton M’f’g. Co.

The Dayton Herald, July 1, 1889, page 3.

The J. W. Sefton Manufacturing Company of Anderson, Indiana survived the legal attack. In 1916, the company sold for $3,000,000. One of their big successes came in 1900, hen “J. T. Ferris of the J. W. Sefton manufacturing Company invented and built the first combination unit for making double-faced corrugated board by machinery”xviii - in other words, cardboard.

Joseph Weller Sefton moved to San Diego in 1890 due to failing health.xix When he died in 1908 “from heart failure, induced by the grippe,” he was considered “one of the wealthiest men on the Pacific Coast.” Like Wilcox, Sefton died at the age of 57.xx His son, J. W. Sefton, Jr, a San Diego banker, famously married the movie star Minna Gombell, promising not to interfere with her career and signing a contract, “specifying that she could go out with unattached males between 3 p. m. and 1 a. m.” whenever they were separated due to business.xxi

The J. W. Sefton Manufacturing Company also made several contributions to the evolution of the paper oyster pail, with no fewer than six related patents filed between 1889 and 1898, one to John L. Sefton (presumably related), two to James Knight of Anderson, Indiana, and three to a man named Ira W. Hollett, of Chicago, who assigned his inventions to the Sefton company.

Prior to contributing designs to Sefton manufacturing, Ira W. Hollett had been business in Chicago making different types of water-tight containers according to what may seem now like an outlandish idea - metal seams. In 1882, Hollett patented the “metal seamed paper sack” (US261851). He filed the patent application in February 1882, and was one of the principals the Chicago Liquid Sack Company was incorporated in March of the same year.

A “metal seamed paper sack” was exactly what it purports to be - a paper sack with seams formed by pressing the edges together with metal strips, instead of adhesives. It was said to provide a “liquid-tight” seal, as opposed to bags sealed with adhesives, which might “leak by contact with the fluid.” He also claimed that the metal strips could be bent or folded at the top to form a carrying handle.

Hollett’s company was in direct competition with makers of “oyster pails” in the style of Heyl, Crume and Sefton. In 1884, Hollett filed an application for a “paper pail” in the already-traditional shape, but using “metal clamps” to form “liquid proof or tight seams,” instead of arranging the folds to make the pail water-tight.

As odd as the design may seem today, it was apparently successful, at least for awhile.

One of the most enterprising and successful concerns in this city is the Chicago Liquid Sack Company, whose office and factory are at Nos. 28, 30, 32 South Canal Street. This company was organized in 1882, and the increase and growth of its business have been phenomenal. They manufacture a very useful article in the shape of paper sacks, pails, and boxes, all water-proof, thus affording a handy, cheap, and convenient article for carrying oysters, syrups, butter, jellies, honey, etc., etc. No glue is used in cementing the seams, metal strips are used instead, making the sack or pail more secure. Among the specialties made by the company are metallic-seamed paper liquid sack and dandy pail, ice-cream and folding boxes, round paper cans, also round and square packages for shelf goods generally. The company ship their goods all over the United States. . . . The officers of the company are J. C. Magill, President; I. W. Hollett, Manager, and H. D. Oakley, Secretary and Treasurer.

Origin, Growth and Usefulness of the Chicago Board of Trade, New York, Historical Publishing Co, 1885-’6, page 301.

In the long run, however, the metal-seam design lost out to the folded paper pail. And if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. Beginning in 1895, Ira Hollett was designing and filing patents for folded paper pails, which he assigned to the J. W. Sefton Manufacturing Company. One of those designs, which was filed in 1898 but not issued as a patent until 1908, appears to incorporate all of the characteristics of the modern “Chinese” take-out container. The final touch was the “cooperating hooks and slits” closure on the top flaps.

Hollett’s unfolded paper blank is similar to Chinese take-out containers still in use today.

The Legacy of the “Oyster Pail”

A century later, the “oyster pail” would be more closely associated with Chinese takeout than with oysters, although insiders still refer to them as oyster pails. The transition is said to have taken place during the post-World War II era in the United States, although Chinese takeout is known to have been served in paper “oyster pails” as early as 1914.

|

| Albuquerque Evening Herald (New Mexico), February 9, 1914, page 6. |

Down to Cases

With Case

TEN MINUTES WITH A CHINESE BILL OF FARE

. . . "Taking order to home pack in oyster pail will be charge extra."

Honolulu Star-Bulletin (Hawaii), January 21, 1924, page 6.

But at that early date, folded, paper “oyster boxes” were as likely to have been used for any number of items, including frequently peanut butter, honey and more commonly, ice cream.

In 1932, Freda Farms capitalized on the strong association between oyster pail-style boxes and ice cream. They designed their new restaurant building on the Berlin Turnpike in Newington, Connecticut as a “Triple Ice Cream Box,” shaped like three “oyster pails.” They also outdid Baskin Robbins, offering “32 Flavors,” more than a decade before Baskin Robbins made “31 Flavors” famous.

.jpg) |

Hartford Courant, May 29, 1932, page 32. |

When they opened a second location in West Springfiled, Massachusetts a month later, it was billed as an “Ice Cream Box,” singular not plural.

|

Transcript-Telegram (Holyoke, Massachusetts), June 30, 1932, page 14. |

Although labeled as the Freda Farms in Connecticut, this building may be their second location, in West Springfield, Massachusetts. It is not the same location as the “triple ice cream box” building because there are no hills behind, as in photographs of the “triple ice cream box” store in Newington.

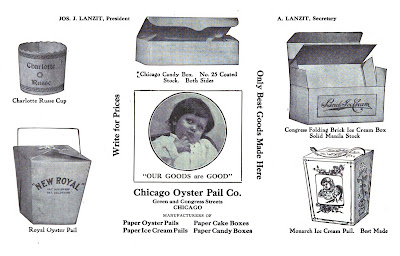

An advertisement for the Chicago Oyster Pail Company from 1907 shows the similarity between boxes they marketed as “Oyster Pails” and “Ice Cream Pails.”

|

Ice Cream and Candy Makers’ Factory Guide, Chicago, Horizontal Freezer Co., 1907. |

The history of the Chicago Oyster Pail Company reveals more in-fighting and drama in the cut-throat oyster pail business. Lanzit had ties to the J. W. Sefton Manufacturing Company. Its President, Joseph J. Lanzit, was one Sefton’s “most formidable competitors” in the oyster pail business. He had previously made boxes for his own company, the Joseph J. Lanzit Manufacturing Company. He was so successful that J. W. Sefton bought him out and hired him to work for them as a salesman. As part of their agreement, Lanzit signed a ten-year non-compete agreement. But it didn’t last.

Lanzit worked for Sefton for one year, and then “entered into relations with the Fred Rentz paper company and the Chicago Oyster Pail company” (the Chicago Oyster Pail company was a partnership between Fred Rentz and a woman named Anna Rafferty, a former employee of Lanzit’s company). Sefton sued and a court found in their favor, enjoining Lanzit from engaging in the oyster pail and related businesses for ten years.

It is not clear whether or to what extent the injunction was enforced, or whether it even remained in force after the initial court rulings. The Chicago Oyster Pail company remained in business throughout the next ten years and beyond. And Lanzit was associated with the company again from at least as early as 1901. Years later, he was connected with the Florida Folding Box Company of Miami (1919) and the Smith-Byer Paper Company in Los Angeles (1920).

|

The services were secured of Joseph J. Lanzit of Chicago, inventor of much of the automatic machinery used in quantity production of paper containers, as superintendent of production.

Los Angeles Times, December 19, 1920, part 5, page 5.

As duplicitous as Lanzit had been, and as disturbing as his legal difficulties with Sefton Manufacturing must have been, it was not the most duplicitous thing he would do and not the most disturbing legal difficulties he would face. In 1924, Joseph J. Lanzit was arrested and convicted of conspiring to murder his wife, a “noted beauty and prominent business woman of Venice, Calif.,” and her closest relative.

Making ardent love to his third wife while he fashioned an infernal machine to blow her to atoms, is the confessed murderous duplicity of Joseph J. Lanzit.

Lanzit, 62, was arrested in the act of planting a dynamite bomb, said by experts to have been powerful enough to raze 50 houses.

The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana), March 28, 1924, page 5 (Note: at the time, “making love” could refer to simple wooing or romancing, not to the physical act as it would suggest today, so it did not have the same impact on contemporary readers as it might to someone reading the headline today. And it did have that meaning in the context of this story, which describes his romancing her with sweet phone calls while planning the attack.).

Oyster pails have since achieved a prominent place in pop-culture as so-called “Chinese takeout” containers. They also achieved a small place in high culture, in the poetry of three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, Carl Sandburg. Sandburg mentioned Lanzit’s Chicago Oyster Pail Company obliquely in his poem, “Clean Curtains.”

“Clean Curtains” appeared in Sandburg’s 1920 collection, Smoke and Steel. It tells the story of a family moving into a home on a busy industrial street corner in Chicago, at Congress and Green, optimistically placing clean white curtains in their windows. In time, however, the dust stirred by hoofs, wagon wheels and rubber tires breaks their spirit and they take down the clean white curtains. One of the factories on the corner is an “oyster pail factory.” Given the location, it appears to be a specific reference to the Chicago Oyster Pail Company, which leased property at 504 South Green Street in 1907.

|

Chicago Tribune, August 30, 1907, page 14. |

The corner of Congress and Green would have been located just west of what is now the western side of the I-90/I-290 interchange.

CLEAN CURTAINS

New neighbors came to the corner house at Congress and Green streets.

The look of their clean white curtains was the same as the rim of a nun’s bonnet.

One was was an oyster pail factory, one way they made candy, one way paper boxes, strawboard cartons.

The warehouse trucks shook the dust of the ways loose and the wheels whirled dust - there was dust of hoof and wagon wheel and rubber tire - dust of police and fire wagons - dust of the winds that circled at midnights and noon listening to no prayers.

“O mother, I know the heart of you,” I sang passing the rim of a nun’s bonnet - O white curtains - and people clean as the prayers of Jesus here in the faced ramshackle at Congress and Green.

Dust and the thundering trucks won - the barrages of the street wheels and the lawless wind took their way - was it five weeks or six the little mother, the new neighbors, battled and then took away the white prayers in the windows?

“Clean Curtains,” Carl Sandburg, Smoke and Steel, New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1920, page 41.

Fred MacMurray and Carole Lombard dined from oyster pails in a taxi-cab in Paramount’s 1935 film, Hands Across the Table.

The rest is history.

i “Small Wonders of Design”: The Chinese Take-out Box,” CBS News, Sunday Morning, May 22, 2016, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/small-wonders-of-design-the-chinese-take-out-box/ .

ii “The Chinese-Takeout Container is Uniquely American, New York Times Magazine, January 15, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/15/magazine/the-chinese-takeout-container-is-uniquely-american.html ; “Small Wonders of Design”: The Chinese Take-out Box,” CBS News, Sunday Morning, May 22, 2016, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/small-wonders-of-design-the-chinese-take-out-box/ ; “Chinese Food Delivery Containers, Explained,” Dana Hatic, eater.com, October 1, 2016, https://www.eater.com/2016/10/1/13110692/chinese-food-takeout-box-history ; “The Surprising Origin of Chinese Takeout Boxes,” Elle Woodside, mashed.com, August 19, 2020, https://www.mashed.com/237997/the-surprising-origin-of-chinese-takeout-boxes/ .

iii US303216, Crume and Sefton, 1884; US262951, Huewe, 1882.

iv “Groundhog Day and Ice Cream Scoops - a History of Ice Cream Scoops from A-Z (Allegheny to Zeroll),” https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2023/02/groundhog-day-and-ice-cream-scoops.html

v US158134, Edward D. F. Shelton, December 22, 1874.

vi US198332, Aulabaugh, 1877.

vii US215309, Wolf, 1878.

viii “Stapler Gallery, Single Shot Staple Machines,” officemuseum.com, https://www.officemuseum.com/stapler_gallery_single_staple.htm ; “The Surprising History and Development of Staplers,” SALCO Stapleheadquarters.com, https://stapleheadquarters.com/the-history-and-development-of-staplers

ix Philadelphia Inquirer, September 28, 1876, page 2.

x Philadelphia Inquirer, October 19, 1882, page 8.

xi Trenton Evening Times (Trenton, New Jersey), June 1, 1909, page 1.

xii For more on the history of paper cup, see my post, "Rewriting Pulp Fiction - an Unabridged History of Paper Cups." https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2023/03/rewriting-pulp-fiction-unabridged.html.

xiii Philadelphia Inquirer, February 4, 1962, Today Magazine section, page 2.

xiv Wilcox was also associated at various times with Wilcox Paper Box Company, the Wilcox-Potter Company and the Duck & Wilcox Paper Box Company.

xv US198332, Aulabaugh, 1887; US215309, Wolf, 1879; US262951, Huewe, 1882; US279992, Tiffany, 1883; US303216, Crume and Sefton, 1884; US382559, Schmidt, 1888; US3961131, Wolf, 1889; US411654, Fogelsong, 1889; US416817, Veneman, 1889; US432029, Fogelsong, 1890; US440656, Fogelsong, 1890; US515820, Crume 1894; US519153, Fogelsong, 1894; US528316, Wolf, 1894.

xvi US196880, William E. Crume and Peter M. Aulabaugh, of Dayton Ohio, Assignors to Aulabaugh, Crume & Co., November 6, 1897 (filed August 2, 1877).

xvii US416810, John L. Sefton, 1889; US571526, Hollett, 1896; US571831, Hollett, 1896; US577863, Knight, 1897; US581028, Knight, 1897; US886058, Hollett, 1908 (filed 1898).

xviii Alexander Weaver, Paper, Wasps and Packages, the Romantic Story of Paper and its Influence on the Course of History, Chicago, Container Corporation of America, 1937, page 70.

xix The Champaign Daily News (Champaign, Illinois), March 27, 1908, page 2.

xx Sacramento Star, March 26, 1908, page 8.

xxi “Marriage Contract Pleases, Extended,” Evening Vanguard (Venice, California), July 9, 1934, page 2.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment