Lead Pipe III – The Final Chapter:

The Malleable History and Etymology of “Lead Pipe” Cinches

The Malleable History and Etymology of “Lead Pipe” Cinches

Introduction

The idiom, “lead pipe cinch,”

denotes a sure thing. But deciphering

the origin of the idiom has been anything but.

In two earlier posts (Horse

Racing and Suicide and A

Stone-Cold “Lead Pipe” Update), I surveyed early examples of the idiom in

print, early stories explaining the purported origin of the idiom, and some

educated guesses about how or why “lead pipe” was chosen as an intensifier for

a regular-old “cinch.” The word, “cinch,”

comes from Spanish. It came into English

through Western cowboys who learned from Mexican caballeros to secure saddles

to their horses using a “cincha” strap.

A “cincha” strap could be tightened by pulling one end of the strap

through two rings, securing it with a cinch-knot. There was no need to secure the strap with a

pin through a hole in the strap, as one might with a typical belt buckle.[i] The word, “cinch,” later came to be used,

idiomatically, to mean having a strong hold on something, and eventually came

to refer to a sure thing.

A “lead pipe cinch” is attested

from as early as July 29, 1888.[ii] It first emerged in horse racing circles,

where a sure bet was a called a “lead pipe cinch.” A “lead pipe cinch” was thought to be even

stronger than an “air tight cinch.” The

imagery of an air-tight cinch is easy to understand. Since “cinch” means to tighten the strap

holding a saddle on a horse, an “air-tight cinch,” suggests cinching tight

enough to make it air-tight.

Purported Origin Stories

A “lead pipe” cinch, however, is more

cryptic. Two early explanations of the

idiom’s origin asserted that the expression was inspired by a drowning incident. The earlier of the two stories, from October

1888, just a few months after the earliest known appearance of the idiom, tells

of a burglar who fell into the water when jumping onto a ferry to cross from

New Jersey into New York City. As he

flounders, his partner takes bets on how quickly his buddy will drown. It’s a sure thing that he will drown quickly;

he knows that his friend has a section of lead pipe “coiled around his waist.” The bet was a “lead pipe cinch.”[iii] In the later story, from 1890, plumber fell

from the East River ferry. He drowned

because he was carrying one of the tools of his trade; he had “a coil of lead

pipe wrapped around his body,” like a belt or a “cinch.” The “lead pipe cinch” was too much for him,

and he drowned.[iv]

Although both of these explanations

sound far-fetched, they both echo details of an actual, widely reported, suicide

from several years earlier. In 1883, a

feather merchant named Robert Cunningham purchased several, high-value insurance

policies; and then jumped from the East River ferry. Witnesses commented on how quickly he disappeared

beneath the waves. When they found his

body several days later, they discovered why he sank so quickly. He had a ten pound bar of lead secured to his

vest by a length of wire. A coroner’s

inquest failed to rule the drowning a suicide, and the insurance policies

apparently paid off.[v]

Since the drowning happened

several years before the idiom is first recorded, it is possible that the suicide

could have inspired the idiom. Perhaps

gamblers admired the risk and payoff.

Perhaps he owed them money. But

the lapse of four years between the drowning and the earliest-known appearance

of the idiom in print may suggest that the idiom was coined, independently,

several years later. The actual drowning

incident may only have inspired the fanciful origin stories, when the new idiom

called to mind the earlier, notorious suicide.

[See also, my Final-Final Chapter - Lead Pipe IV; A Lead Pipe Could Be a Sure Thing Even Before it was a "Cinch"]

Why Lead Pipe?

If the idiom developed

independently, unrelated to the drowning, it is not immediately clear how or

why a “lead pipe” came to represent a particularly strong “cinch.” I imagine a “lead pipe” as something that is

stiff and rigid, like the stainless steel drain pipes under my kitchen sink; something

the lead pipe that Colonel Mustard or Mrs. Plum might have used to bonk Mr.

Boddy, on the head, in the billiards room, in the board game Clue (or Cluedo). The image of using a pipe as a cinch does not

ring true.

Lead also seems to be an unlikely

candidate to denote strength. As metals

go, lead is soft, malleable, and easily deformed. It seems that iron, steel, or any other

strong metal or material, would have been more logical choices. Although lead is presumably stronger than a

rope or other strap that might be used as a cinch on a horse, what is it about

a lead pipe that would make susceptible to being used as an intensifier for “cinch.”

Ironically, perhaps, it may be lead’s

weakness that holds the clue to why it was used to denote a strong cinch. In the

late-1800s, lead pipes were sold in coils, much like a coil of rope. Lead pipes were also freely, and easily,

bendable, and could be bent into knots.

It was not beyond reason to imagine using a lead pipe as a strong cinch. The public perception of the easy malleability

of lead pipe is illustrated by a story of a lead-pipe attack gone wrong:

Securing a section of lead

pipe, he hid in a doorway, and when a strapping big fellow happened to come

along he hit him a terrific blow on the back of his bull neck. The lead pipe wrapped around the big man’s

throat like a scarf, and he walked off with it whistling ‘Annie Laurie.’

Evening Star (Washington DC)September 22, 1899, page 13.

The form of the idiom is also

consistent with the form, “[BLANK] cinch,” where the [BLANK] is replaced by any

of a number of other materials that could be used to make a cinch, literally or

figuratively. The strength of a “lead

pipe cinch” lies in the fact that lead is stronger than an actual “rope cinch,”

or “leather cinch.” A “barbed wire cinch” is another type of strong cinch, and

the lowly “string cinch” is just the opposite, a sure loser.

Coils of Lead Pipe

In the late-1800s, lead pipe was

not anything like the rigid, stiff, stainless steel pipes under my kitchen

sink. They seem to have been more like

the copper tubing in my water supply; the kind of tubing that even I could bend

into a pretzel. Lead pipes were

manufactured and sold in coils, not unlike coils of rope. The practice is spelled out in a patent

issued in 1882, for an improvement in the method of manufacturing lead pipes:

In the manufacture of lead pipe

it is customary to wind it on a cylindrical drum or reel into bundles or coils

in order to put it into convenient for for subsequent handling . . . .

US Patent No. 269651, dated

December 26, 1882, to John Farrell, of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.

Such “coils” were available for

sale in various lengths:

The length of a coil or bundle

of lead pipe for ¼ in., 3/8 in., ½ in., and 1 in. pipes is 60 ft. Sometimes 1 ¼ in. pipe runs 60 ft., but this

is too heavy a bundle. The coil or

bundle of 1 ¼ in., 1 ½ in., 1 ¾ in., and 2 in. pipes is 36 feet long.

Philip John Davies, Standard Practical Plumbing: Being a

Complete Encyclopaedia for Practical Plumbers and Guide for Architects,

Builders, Gas Fitters, Hot Water Fitters, Ironmongers, Lead Burners, Sanitary

Engineers, Zinc Workers, London, E. & F.N. Spon, Ltd., 1889, Volume 1,

2d Ed. Revised, page 36.

The ease with which it could be

bent was one of the advantages of using lead pipe:

It has this great advantage

over cast-iron pipe fitting, that lead pipe, by the skilled plumber, can be

bent on the spot exactly as it is

wanted.

S. Stevens Hellyer, Lectures on the Science and Art of Sanitary

Plumbing, London, B. T. Batsford, 1882, page 63.

Although a certain amount of

skill and technique were required to bend larger pipes, smaller “pipes” were

easily bent:

Small

Pipe Bending.

For small pipes, such as from ½

in. to 1 in. “stout pipe,” you may

pull them round without trouble or danger; but for larger sizes, say, from 1 ¼

in. to 2 in., some little care is necessary, even in stout pipes.

Davies, Standard Practical Plumbing, London, E. & F. N. Spon, Ltd., 2d Edition, Revised, 1889, page 96.

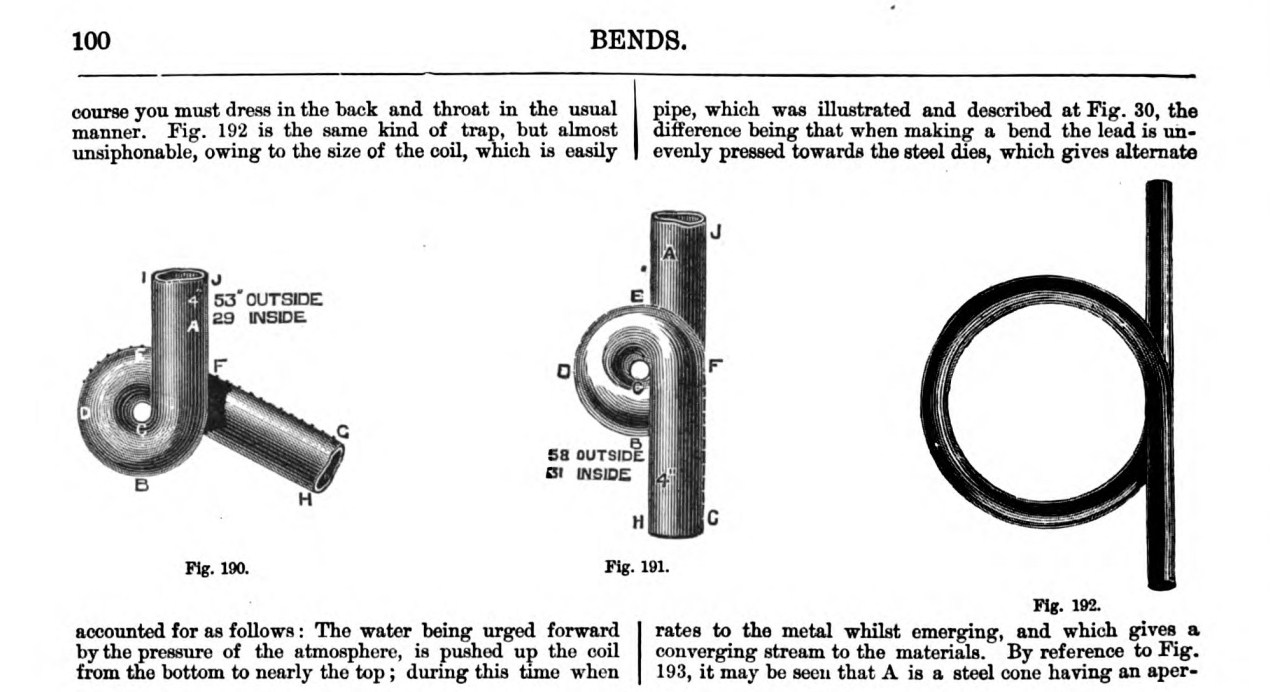

Plumbing handbooks from the time

include lengthy chapters on techniques for bending pipes. Plumbing diagrams generally showed how the

pipes should be bent in place. They did

not suggest, and the catalogues did not generally supply, pre-bent sections of

pipe. “Lead pipes,” even pipes up to two

inches, could be bent into crazy shapes:

Lead pipes had common household

uses; being commonly used in water supply and drainage, and gas supply. Although the dangers of lead poisoning were

known in the 1880s, water supply pipes were often lined with copper, or copper

alloy, increase the strength of the pipe, and reduce the risk of lead poisoning. But lead pipes were still used in household

drainage systems; they had not yet learned to address the long-term, harmful

effects of lead leaching into the environment.

Lead pipes also had industrial

uses. They were often used as heating

coils, or condenser coils, in chemical processes. They were frequently used in distilling

processes for various chemicals, including moonshine.

Lead pipe is still used for various industrial applications; and is still manufactured and sold in coils, and bent to to the desired shape.

Lead pipe coils appear to have

been well-known, common, and widely available in the late-1800s. They were so well-known that both of the

early, purported origin stories referred to “coils of lead pipe,” instead of

the lead bar and wire that were reported in the original suicide on which those

stories were based.

Lead pipe coils were also common

enough to be fodder for stupid jokes:

When a coil of lead pipe in

front of a hardware store begins to wiggle and stick out its forked tongue a

Dakota man knows it is time to swear off.

Saving the country by putting

the Bryan men in power would be like throwing a drowning man a coil of lead

pipe for a life preserver.

Potosi Journal (Potosi, Missouri), August 1, 1900, page 1.

A section from a coil of lead

pipe was featured prominently in a story about a man who was cheated by the

butcher. The butcher had apparently hidden

a small coil of lead pipe inside a turkey, to increase the sale price of a

turkey priced for sale by the pound. A

sketch that accompanied the article shows a curved, nearly round, coil of

small-diameter “lead pipe” that looks more like a Polska

kielbasa than what I normally think of as a section

of pipe.

Coils of lead pipe were so common

that an autopsy on one of Barnum’s elephants (Jumbo’s widow, Alice), revealed a

“small coil of lead pipe” in her stomach.[vii] She also had three or four-hundred pennies,

part of a jack-knife, and a miscellaneous collection of pebbles in her

stomach. She did not die from eating too

much junk; she died in a tragic fire that also took the life of several other

elephants, including the famous “white elephant,” Toung Toulong.[viii]

[Blank] Cinch

The syntax of the idiom, “lead

pipe cinch,” is consistent with the syntax of other literal, as well as

idiomatic, uses of the word cinch; “[BLANK] cinch,” where [BLANK] represents

some material from which the actual, or proverbial, cinch is made. There were actual, “rope cinches” and

“leather cinches,” and figurative, “barbed wire cinches.” I found one reference to a figurative,

“string cinch,” which was the opposite of a “lead pipe cinch” – it was a sure

loser, or easy mark. Metaphoric cinches

could also be intensified, or strengthened, by cladding, binding, fastening, or

riveting the cinch with copper. The

expression, “steel cinch,” also appeared in print on several occasions; often

in reference to J. P. Morgan’s monopoly on steel.

Rope Cinches

When a rope was used to tie, or

secure, something, it could be called a “rope cinch”:

Live local from the Home Index:

Over 70,000,000 pairs of suspenders were made in the United States last year,

yet half the men around here wear a hay-rope cinch to keep the slack[ix]

of their trousers out of the mud.

The Morning Call (San

Francisco, California), May 20, 1890, page 1.

An effort was then made to

start Peeples [(at shortstop)], but he wouldn’t budge. Several suggestions were offered, such as

feeding him dirt, putting a rope cinch on his nose and twisting it, pouring

water in his ear and building a fire under him.

None of these remedies, however, were deemed expedient, so a young man

named Armstrong, lately signed, was put to work at short, while the other man

sat on the bench and sniffled.

The Morning Call (San Francisco, California), June 19, 1891, page

2.

He kept the

company of matadors busy every moment of the time for more than a quarter of an

hour. Then he was lassoed head and foot,

thrown and a rope cinch tied about him.

A Mexican mounted and rode the animal, the toreadors keeping up the

former exercises.

The San Francisco Call (San Francisco, California), September 17,

1895, page 4.

A race with wild steers for

mounts is on the program of the Elks’ rodeo at Klamath Falls. A rope cinch will be used instead of a

saddle, and contestants will be allowed a rope-and-tail hold.

Daily Capital Journal (Salem, Oregon), July 4, 1913, page 2.

Leather Cinches

When a band of leather is used to

bind, or secure something, it could be called a “leather cinch.” There are dozens of references to “leather

cinches.” Although most of those

references refer to straps used to secure a horse to a saddle, a wagon, or to

cargo on the back of the horse, “leather cinches,” could also be used as hat

bands and women’s girdles or belts:

I saw one man at church who

wore a massive Mexican hat with two or three pounds of silver braid on it, and

a leather cinch with two silver buckles for a band.

The Salt Lake Herald, April 19, 1891, page 13.

The Evening World (New York), July 25, 1892, page 2.

Barbed Wire Cinches

The less widely used idiom,

“barbed wire cinch,” enjoyed a brief lifespan.

When Guglielmo Marconi (the

inventor of the “wireless” telegraph) lost his fiancé, a clever writer joked:

What does it profit a young

inventor to devise a wireless telegraph and lose his girl? The next time Marconi gets a fiancée he had

better put a barbed wire cinch on her.

You can’t hold the modern maiden by the wireless process.

The San Francisco Call, January 29, 1902, page 6.

When a Kentucky politician advocated

a two-cent whiskey tax, a reporter speculated:

And it’s a barbed wire cinch

that he meant every word of it.

Daily Public Ledger (Maysville, Kentucky), March 27, 1906, page 2.

A candidate for office in

Tombstone, Arizona promised:

Now, I won’t ask the cowboys

and ranchers to come more than fourteen miles just to vote for me, as, of

coarse, I have a barb wire cinch anyhow.

Tombstone Epitaph, September 20, 1908, page 4.

String Cinch

Rope cinches and leather cinches

were functional. Metaphoric “barbed

wire” and “lead pipe” cinches were secure.

But the lowly “string cinch” was something less desirable – a sure

loser. The expression appeared in an

account of a baseball game involving actors and newspapermen:

Giffen pitched a wonderful

game, sending one man to base on balls and striking out a man in the sixth

inning. Smiley was always so busy

adjusting his face and his whiskers and his sweater that he never hit the ball

and the opposing batter regarded him as a string cinch.

St. Paul Daily Globe (Minnesota), June 26, 1895, page 4.

Since I could only find one

example of the expression, “string cinch,” I would not call it an idiom. But the expression did follow the familiar,

“[BLANK] cinch” format, in which [BLANK] is the name of the material used to

make the cinch. It is therefore further

evidence that the idiom, “lead pipe cinch,” may have been an allusion to using

a length of bendable, lead pipe coil, as a cinch.

Copper Bound/Lined/Fastened/Riveted

Cinches

Lining a lead pipe with copper

increases the strength of the pipe, while maintaining many of its beneficial

characteristics:

A metaphorical cinch could also

be strengthened by binding, lining, fastening, riveting, or otherwise strengthening

the cinch, with copper:

Lentilhon has a copper-bound

cinch bet on Sherrill.

The Sun (New York), May 9, 1889, page 6.

“I’ve had a good many hard turns in this

line,” he said. “Dead sure things gone

wrong! Copper fastened cinches left at

the post! And all that sort of demoralizing business, but an experience I had

in Chicago a few years ago beat all else hollow in a long and, by no means,

uninteresting career of playing horses.”

Lawrence Democrat (Lawrenceburt, Tennessee), October 2, 1891, page

1:

In race course language, the

owners look on it as a copper-lined lead-pipe cinch.”

The Sun (New York), November 22, 1891: page 3,

“The track will be heavy

tomorrow, and I’ve got a copper riveted, lead pipe, copyrighted, air tight

cinch. Firenze in the mud – she swims in

it – She can make th pace so hot that the track will be dry before she does the

first quarter.”

Los Angeles Herald, November 12, 1891, page 10.

Steel Cinches

In 1901, when J. Pierpont Morgan

(the model for the Monopoly mascot, Uncle Pennybags, and grand-father of Real Housewife of New York, Sonja Morgan's, ex-husband) cornered the world steel

market, the phrase “steel cinch” came into limited use for a brief period of

time. A cartoon that appeared in

Harper’s Weekly show Morgan securing a steel cinch around the world:

The phrase was used again in 1905

when the Sultan of the

Ottoman Empire awarded Morgan the “grand cordon of the Osmanli order.” In this context, the phrase worked on several

levels; as a reference to Morgan’s control of the steel industry, and by an

oblique reference to rope, which could be used to tie a cinch (“cordon” is the French word for rope):

The important news comes from

Constantinople that the sultan has conferred on J. Pierpont Morgan “the grand

cordon of the Osmanli order.” Although

there is doubt in the minds of Mr. Morgan’s countrymen as to what sort of thing

that grand cordon is, the sultan’s compliment to our eminent fellow-citizen is

appreciated at its full value. It will

match nicely with the distinction conferred on Mr. Morgan by the American

public – “Grand Commander of the Steel Cinch.”

Los Angeles Herald, May 8, 1905, page 6.

The expression received a more

down-home treatment a few years later:

“Gents,”

he says, “you’ve hearn what the ‘greement is.

An’ now I wanter say let every gent put up every cent he’s got ‘cause

this is a cinch. You know me an’ you

know that when I says I’ve got a cinch I’ve got a real one – a double riveted,

reinforced Bessemer steel cinch.”

The San Francisco Call,

September 27, 1908, page 12.

Diamond and Double-Diamond

Cinches

At about the same time that the idiom,

“lead pipe cinch,” came into use on the East Coast, an alternate expression

could be heard in the American West, where the idioms, “diamond cinch” and “double-diamond

cinch,” was used metaphorically, to describe a having firm grasp on

something. But despite the well-known

strength of diamonds, the “diamond” in a “diamond cinch” does not relate to the

gemstones, it the diamond-shape described by a portion of a rope used to secure

a load on the back of a pack animal. The

“diamond” hitch and “double-diamond” hitch

procedures are still in use today.

The “double-diamond hitch” was in

use at least as early as 1872:

With one accord we dismounted,

adjusted our cinches, made everything secure about our saddles, put the

double-diamond hitch to the pack (a feat which none but Prof. Raymond could

perform), after which that pack and that horse were one and the same thing;

then we took again our places in the saddle.

The New North-West (Deer Lodge, Montana), June 1, 1872, page 2.

In 1878, “diamond cinch” was used

figuratively, in the sense of putting a stop to something by cinching it, as

opposed to the later sense of being a sure-thing:

Right here we draw the “diamond

cinch” on all this nonsense. – Helena (Mon.) Herald.

The Stark County Democrat (Canton, Ohio), March 28, 1878, page 2.

In 1889, an article about slang

included a section explaining the word cinch, and related idioms:

Everybody has heard “cinch”

used as the equivalent of a sure thing.

In loading burros or other pack animals of the far West, the packer

fastens the burden with ropes, which he ties around the animal’s body with a

peculiar knot. It never works loose, no

matter how rough the road. In Western

towns to-day a “diamond” or “double-diamond cinch” expresses a sure thing that

cannot possibly fail. New Yorkers draw

the knot somewhat closer, and when they grow emphatic speak of an “air-tight

cinch,” frequently abbreviated to “air-tight.”

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Washington), February 26, 1889,

page 7.

The phrase was still in idiomatic

use in 1894:

For some time past negotiations

have been pending and concerted effort made on the part of the Denver and Omaha

smelters to gather under their protecting wing the Salt Lake valley smelters,

and thus have what is termed in western parlance a “diamond cinch” upon the

mine owners and ore purchasers of this section.

Omaha Daily Bee (Nebrask), March 30, 1894, page 1.

Conclusion

In 1888, when the idiom, “lead

pipe cinch,” first appeared, lead pipes were sold in coils (like rope), and

were freely bendable (like a rope). It

would not have been much of a stretch to imagine wrapping a coil of “lead pipe”

around a horse to make a particularly strong cinch. The format of the idiom (“[BLANK] cinch”) is

consistent with format of expressions used to describe actual cinches, like “rope

cinches” and “leather cinches.” The form

of the idiom is also consistent with the form of other, less well-known

expressions (“barbed wire cinch” and “string cinch”), in which the material

being figuratively used for a cinch is more obviously rope-like.

It is therefore plausible, if not

likely, that the expression “lead pipe cinch” originated as an allusion to bending

a “lead pipe,” or lead tubing, into a particularly strong cinch. Although lead is not a particularly strong

metal, a lead pipe is certainly stronger than rope, leather and string.

I wouldn’t say it’s a “steel

cinch,” although it is at least a “barbed wire cinch.” It’s certainly more likely than a “string

cinch.”

It’s a “lead pipe cinch.”

[i] American Notes and Queries, volume 5,

number 17, August 23, 1890, page 197.

[ii] ADS-L

(American Dialect Society, Internet discussion group), July 10, 2010 (message

by Garson O’Toole, reporting find by Stephen Goranson). “They considered Lucky Baldwin’s great filly

Los Angeles a “lead pipe cinch,” and put their money on at any odds.” Boston

Sunday Globe, page 6, column 2.

[iii] The

New York Tribune, Octobe 8, 1888, page 12 (see my earlier post, A

Stone-Cold, Lead-Pipe Update).

[iv] Pittsburg Dispatch, April 27, 1890, page

20, column 8 (citing The St. Louis

Republic) (see my earlier post, Horseracing

and Suicide).

[v]

See my earlier post, Horseracing

and Suicide – the Heavy History and Etymology of “Lead-Pipe Cinch”.

[vi]

The allusion to seeing snakes, when drunk, is a precursor to the stereotypical,

drunken hallucination, the “Pink Elephant.” See my earlier post, The

Colorful History and Etymology of “Pink Elephants.”

[vii] The Doctor, Volume 1, Number 23,

November 16, 1887, page 5.

[viii]

See my earlier post, Buddhism

and Baseball – White Elephants and the White Elephant Wars.

[ix]

Note how the reference to the, “slack of their trousers,” hints at the origins

of the word, “slacks,” for pants.

No comments:

Post a Comment