|

| "The Mulligan Guard Lies But - Surrenders" (Puck, 1884 - a precursor of "Mulligan Stew"?) |

Mulligan

Stew is “a stew made from whatever ingredients are available.”[i] In the early 1900s, it was closely associated

with hobos or tramps who would make stew with whatever they could get their

hands on:

On Monday this band of vags [(vagabonds)]

started out to work the town which is probably the only work they have been

guilty of for many a moon. They held up

all our store people for grub in different forms, and later on assembled below

town to cook it. Near the Monarch mine

they started the fires, and with old apple cans to serve as pots, began the

manufacture of a Mulligan stew.

The Neihart Herald (Neihart, Montana),

July 18, 1896, page 3.

Now I know

why the Lady was a Tramp:

She wined and dined on

Mulligan Stew . . . that’s why the lady is a tramp!

Rodgers and

Hart, “The Lady is a Tramp,” from Babes

in Arms.

(Lady Gaga and Tony Bennett sang

“The Lady is a Tramp” (although they skip the opening verse and its

mulligan stew line).)

But why is

it a “Mulligan” stew? A “mulligan stew”

is frequently described as being similar to an “Irish stew,” so perhaps

Mulligan, an Irish surname, is merely a placeholder name indicative of its

Irishness; as others have surmised.[ii] But “Irish stew,” itself, was already used

idiomatically, on occasion, from as early as 1805, with a meaning similar to

“Mulligan stew”; something thrown together from random, disparate elements at

hand.

Which raises

the question, why “Mulligan”? The answer

may lie in a popular play about a rag-tag Irish militia outfit in New York City

. . .

The Mulligan Guard Chowder

. . . which featured

a chowder made with a cat. And of

course, if you make a chowder with a cat, isn’t it really a stew?

Coincidentally

(or not?), the earliest examples of “mulligan stew” in print related to another

group of rag-tag militia units; “Coxey’s Army.”

Coxey’s Army and Mulligan Stew

In 1894, the

United States was in the second year of what would be a four year long

depression; the worst depression in history up to that time. To protest the economic policies that

contributed to the Panic of 1893, and to lobby for the creation of a government

jobs plan that would pay workers with paper currency, Ohio businessman Jacob

Coxey organized an army of workers to march on Washington; and inspired workers

in other parts of the country to organize similar armies to mount similar

marches. These rag-tag militia-like

units were collectively known as, “Coxey’s Army.”[iii]

An army

marches on its stomach, and Coxey’s armies (or at least some of them) marched

on “mulligan stew.” All of the earliest

examples of “mulligan stew” I could find in print related to feeding Coxey’s

armies:

Contributions of food came in

liberally yesterday . . . . The meat and

potatoes were stewed together into what is called Mulligan

stew, “because it goes further that way,” as Commissary Brown put it.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Seattle,

Washington), April 12, 1894, page 5.

Tensions

were high two weeks later, when one wing of the “Industrial Army,” under the

command of “General” Hogan, commandeered a train in Montana to transport their

members to Washington DC. The real militia

was called out, and there were rumors that the federal government was sending some

“regulars,” including four companies of the so-called “Buffalo Soldiers,” who

were stationed at Fort Missoula, Montana.

Through it all, the workers (or wannabe workers) ate “mulligan stew”:

Rations were served to each

company and the men had what they called a “mulligan,”

which consisted of a kind of Irish stew made of the scraps left over

from the former meals.

The Anaconda Standard (Anaconda,

Montana), April 24, 1894, page 4.

A few months

later, a boatload of Coxeyites from the Northwest ate “mulligan stew” while

passing through Detroit on their way to Washington DC:

Dinner was served today between

the hours of 2 and 4 o’clock. . . . The

bill of fare consisted of “mulligan,” which closely

resembles an Irish stew, potatoes, and black coffee. “Mulligan” was the

favorite and the men passed up their tin cans for refilling “full many a

time and oft.” Two or three men were

having their hair cut while dispatching the delectable stew. The floor is used for a table and the men eat

with their fingers or improvised wooden spoons.

The cooking was done with oil stoves.

The stew was boiled in a battered old boiler and the coffee was prepared

in an ex-water pail.

The Inter-Ocean (Chicago, Illinoi), July

23, 1894.

Other

unemployed men, some of whom were headed to Washington DC to join the Coxey

Army, enjoyed “Mulligan” stew on the road during the same period:

I soon found out they were on their way to Washington; two with the

avowed intention of joining the commonweal army,

the others on one of the aimless expeditions that go to make up the sum of

existence for these latter-day nomads. . . .

During the afternoon Oakland bought his keg of beer, and on its arrival

in camp it was voted unanimously to hold it until the next day and then to

celebrate the day by cooking a “mulligan.” Now,

mulligan is a stew of large proportions and many ingredients, and, as it

would require considerable hustling to get together the stuff, we all started

early. To my share fell the tomatoes and

potatoes. Army was to get coffee, sugar,

salt and pepper, and the rest were to provide meat, bread, and if possible,

chickens.

The Evening Star (Washington DC), May

17, 1894, page 3.

Although

there is no direct evidence that “Mulligan stew” was a reference to “The

Mulligan Guard Chowder,” the coincidence of a rag-tag army of workers eating

“Mulligan stew” and a rag-tag Irish militia eating “Mulligan Guard chowder” may

at least raise an eyebrow. It seems

plausible that someone in Coxey’s Army could have used “Mulligan stew” as a

playful, pop-culture reference to “The Mulligan Guard Chowder.” And even if the term did not originate in

Coxey’s Army, it may nonetheless have been a reference to what had been a

popular play fifteen years earlier.

“Mulligan

stew” also owes a debt of gratitude to “Irish stew”.

Irish Stew

The Irish

have long been associated with stew.

“Irish Stew” appeared in cookbooks as early as 1802.[iv] The early recipes were generally pretty

simple, and required very few ingredients; usually mutton (or optionally, beef),

potatoes and onions, and sometimes thyme, parsley and/or carrots.

|

| Duncan MacDonald, The New London Cook, London, Albion Press, 1808, page 367. |

But despite

the simplicity of the recipes as they appeared in cookbooks, such stews were

apparently known for being amenable to mixing whatever old or fresh ingredients

were lying around. As early as the 1805,

“Irish Stew” was used idiomatically, to refer to thing made up of random

collections of various ingredients; suggesting, perhaps, that some Irish stews

may already have had something in common with what we now call a Mulligan stew.

In 1805, a writer

likened the craft of writing poetry to the making of an Irish stew:

To the Author’s Grandson.

Into my room whene’er you

pop,

You think it is some workman’s

shop,

A Poet’s shop – where

scraps and scratches,

Made like a

motley quilt of patches;

. . .

A queer mixt

medley, old and new,

Just as you make

an Irish stew;

The Poet thus

crams things together,

And stirs them with a

Goose’s feather.

Mr. Pratt

(Samuel Jackson), Harvest-Home,

Volume 3, London, Richard Phillips, 1805, page 57.

In 1810, a

theater critic described production

thrown together from old bits as an “Irish stew”:

Mr. Arnold’s Christmas

dish, an Irish-stew, made up of old materials,

appeared for the first time on the 26th.

The Monthly Mirror (London), January,

1810, page 65.

“Irish stew”

was also used figuratively in the United States, from time to time. In 1869, a review of the play, “An Irish

Stew, or the Mysterious Widow of Long Branch,” for example, described the cast

of characters as being, “mixed up in a regular Irish

stew through the intolerable intermeddling of Mr. Macglider as a

peace-maker.”[v]

In 1886, a

headline critical of inconsistent reporting in British newspapers as concocting

“an Irish Stew With Socialistic Seasoning.” Several London newspapers had apparently

written editorials likening anarchist terrorists convicted of murder in the Haymarket Affair with

pro-Irish independence agitators, like Jeremiah

O’Donovan Rossa, in the United States.

Britain was then trying to negotiate an extradition treaty with the

United States that would enable them to get their hands on those “political”

criminals. The American writer believed

that comparing convicted political murderers to political agitators was a false

equivalence.

|

| Omaha Daily Bee (Nebraska), August 21, 1886, page 1. |

In 1887, an article about a Mexican dinner served at a

banquet in Philadelphia described one of the dishes as, “Mexican-Irish stew”:

. . . “Puchero,” which

came next, was made of fried cabbage, goat meat, fried carrots and fried

bananas, and is known as a “Mexican-Irish stew.”

Arizona Weekly

Enterprise (Florence, Arizona), June 18, 1887, page 1.

Since “Irish

Stew” was sometimes regarded as a mix of incongruous elements, perhaps it was

inevitable that a common Irish name, like Mulligan, would become the name of a

“stew” made from whatever one has on hand.

But why

Mulligan in particular? Like many

catch-phrases and new expression, its origin may have been on the stage. In this case, its origins may stem from the

well-known team of Irish comedians, Harrigan and Hart.

Irish Comedians

Hogan &

Hart were one of the most successful comedy teams, producers and theater owners

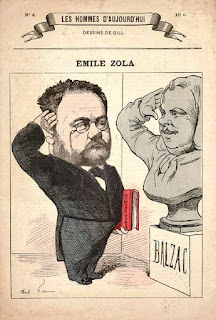

of the late nineteenth century. In 1879,

The New York Times referred to them as “ernest disciples of the type of gritty

realism pioneered by Honore Balzac and Emile Zola.”[vi]

The reviewer

compared Hogan & Hart’s series of “Mulligan Guard” plays to Zola’s series

of Les

Rougon-Macquart novels; stories about the lives of a middle class family

during the Second Empire.

The

“Mulligan Guard” series focused on the lives of members of the middle or lower

classes in New York City. The title

characters were members of a neighborhood Irish militia company. Other characters in the plays included

members of a neighborhood black militia, the Skidmore Guards, captained by

Simpson Primrose and the Reverend Palestine Puter; and a German couple,

Gustavus Lochmuller and his wife Bridget.

Although the plays were considered low-brow entertainment (the New York

Times reviewer assumed that names, Hogan & Hart, were only “vaguely

suggestive” to its readers), Hogan & Hart’s Theatre Comique was the most

successful theater in the city; and the Times gave them their stamp of approval:

Harrigan

and Hart were formerly “variety performers,” and were highly esteemed in their

profession. This was their chrysalis

state, for they soon developed in the butyterfly state of managers, and the

Theatre Comique was their fertile garden.

Here they established the old-fashioned sort of song-and-dance

performance, though it was soon observed that they were an unusually ambitious

couple. As time wore on, they began to

introduce novelties into their business, and, thanks to their association with

an able musician – Mr. David Braham – they were soon able to carry out an idea

which had been fermenting in the brain of Mr. Harrigan. The latter conc eived the project of placing

upon his stage a series of plays depicting low life in New York, interspersed

with original melodies. The author of

the Rougon-Macquart novels, it is

needless to say, proceded from the same starting point. Well, Mr. Harrigan wrote “Tue Mulligan

Guards’ Picnic,” and Mr. Braham gave the piece a musical seting. The success of the novelty was remarkable,

and it was soon followed by another play of the same sort, “The Mulligan

Guards’ Ball,” then by “The Mulligan Guards’ Chowder.”

[Their]

plays have presented the same characters in new situations, and are connected

in the manner of a magazine story, which is published serially. Mr. Harrigan’s central purpose seems to have

been to give a realistic picture of life among the poor wards of our City,

although he has never hesitated to sacrifice realism to farce. . . . The basis

of his work is simple Irishmen, Germans, and negroes figure in the story, and

the absolute impossibility of these three elements of nationality to live in

concord furnishes its amusing texture.

The New York Times Theater Reviews,

1870-1885, New York, The New York Times & Arno Press, 1975 (1879 D 21,

7:2).

The lower

classes depicted in the plays were also fans.

This etching depicts an audience watching the “thrilling spectacle of

the march of the Mulligan Guards” – with the guardsmen all decked out in

mismatched, non-uniform uniforms:

An image

from the novelization of the first episode of the Mulligan Guard shows the

“march of the Mulligan Guards” as they go home after a day of drilling and a

“target shoot.” The joke of the episode

was that they never could hit the target during the drill, so they had to

literally “drill” holes in the wooden target in order to salvage their

reputation.

|

| The History of the Mulligan Guard, New York, Collin & Small, 1874, page 28. |

The song

from the “Mulligan Guards,” was popular enough, and ubiquitous enough, that an

Italian organ grinder had the song on his organ in 1878, when he was still in mourning

over the recent death of King Vittorio

Emanuele II:

An organ-grinder struck the

town yesterday with his organ draped in mourning for the dead King. His silent token of his grief was very

touching until he began to grind out “The Mulligan

Guards.” – Oil City Derrick.

Puck (New York), Volume 2, Number 47,

January 30, 1878, page 13.

When the

“Mulligan Guard Chowder” debuted in 1879, the New York Times gave it a

favorable review:

“The Mulligan Guard's

Chowder” . . . is a very broad and

realistic sketch of low life, but an irresistibly comic one.

The New York Times Theater Reviews,

1870-1885, New York, The New York Times & Arno Press, 1975 (1879 Ag 22,

5:2).

One

advertisement for the play suggests that the chowder was made, like “Mulligan

stew,” with random ingredients – including a “cat” or wild tomcat (proper name

Thomas):

The New York Herald, September 14, 1879,

page 4.

A summary of

incidents in the play, published in another advertisement, seems to confirm

that the chowder may have been made with a cat; at least a cat is featured in

the plot. In scene 6, the action moves

from Manhattan to the “Jersey Beach,” where there is some fishing, clam

digging, a “Hot Chowder,” a funeral, and the “Appearance of the “Felis

Maniculatus” – a cat (or a rat? [vii]). The song that follows, “Dolly and Kitty and

Mary So Pretty,” may be about a woman named Kate, or could a reference to the

cat.

Although the

scanty evidence does not prove a connection between the “Mulligan Guard

Chowder” and “Mulligan stew,” the extended period of popularity of the “Mulligan

Guards,” generally, suggests that the connection is possible. The “Guard” were still popular enough during

the mid-1880s that several political cartoons in Puck were modeled after them:

|

| Puck (1884) |

As late as 1893,

Harrigan was still performing the “negro burial” bit from the “Mulligan Guard

Chowder.” Since that incident appeared

in the same scene as the chowder incident, he may well have still been

performing the chowder bit. Although I

could not find any specific reference to his performing the “chowder” bit into

the 1890s, he or others may have kept it alive:

It is a pity that Mr. Harrigan cannot

infuse the same up-to-date spirit into his productions, but the truth is that

of recent years he has raked over his old material too thoroughly, and,

besides, dozens of imitators have arisen with plays modeled on the ones that

made him famous long ago, and now the public has grown a little tired of those

phases of negro, Irish, and Italian characters which constitute Mr. Harrigan’s

chief stock in trade.

The Sun (New York), August 31, 1893,

page 5.

Ed Harrigan

kept the “Mulligan Guard” characters and situations alive in the early 1900s,

when he published a collection of “Mulligan Guard” stories.[viii] Although the book did not include the cat-chowder

incident from “The Mulligan Guard Chowder,” there are several references to chowder

in the book.

Although none of this proves that the

“Mulligan Guard Chowder” was, in fact, the inspiration for “Mulligan stew,” it

seems like a plausible explanation. And,

if “Mulligan stew” was inspired by a fictional “Mulligan Guard Chowder,” the

“Mulligan Guard,” itself, may have been inspired by actual events.

Irish

Militia

Neighborhood

militia units were a common feature of life in New York City, and many of them resembled, in one way or another, the fictional “Mulligan Guard”:

There are a great number of

militia companies in New York, and some of them are really very martial-looking

indeed. I am told there is a company of

Highlanders, formed by the sons of far Caledonia; and there are German, French,

Italian companies, &c. There are a number

of target companies, each known by some particular name – usually, I believe,

that of a favourite leader who is locally popular among them. . . .

A few of them are “The Washington Market Chowder

Guard” (chowder is a famous dish in the United States), “Bony Fusileers,”

“Peanut Guard,” “Sweet’s Epicurean Guard” (surely these must be confectioners),

“George R. Jackson and Company’s Guard,” “Nobody’s Guard,” “Oregon Blues,” “Tenth

Ward Light Guard,” “Carpenter Guard,” “First Ward Magnetizers” . . . and

multitudes of others.

. . .

Generally a target, profusely

decorated with flowers, is carried before the company, borne on the stalwart

shoulders of a herculean specimen of the African race, to be shot at for prize and

glory, and the “bubble reputation” alone.

On its return from the excursion and practice, the target will display

many an evidence of the unerring skill and marksmanship of the young and

gallant corps.

Lady

Emmeline Stuart-Wortley, Travels in America,

Volume 1, London, Richard Bentley, 1851, pages 298-299.

The fictional “Mulligan Guard” may also have been based on a real-life “Mulligan Guard”:

At a Meeting of the James Mulligan Guard, held at their headquarters 125

Grand street, on Thursday evening, April 2, a full attendance being present, it

was unanimously resolved to have an election for officers for the spring

parade, and the following gentlemen were unanimously chosen: . . . Patrick

McDonald; . . . Donahoe; . . . Donnelly; . . . Rourke; . . . Doyle; . . .

Stuart; . . . O’Connor. After election

the members retired to an adjoining room and filled their bumpers [(glasses)]. The first toast was given to the Hon. James

Buchanan, President of the United States; the second was the Army and Navy; the

third, the James Mulligan Guard, one and

inseparable; fourth, The Man whose name we bear; all of which were drank with

three times three [(three cheers; three times)], and interspersed with various

appropriate songs.

The New York Herald, April 5, 1857, page

7.

The name and

ethnic makeup of the real and fictional militia units is not the only

similarity between the two. The life of

the real-life James Mulligan, patron of the real-life Mulligan Guard, closely

parallels the life of Terrance Mulligan, the fictional patron of the original

fictional “Mulligan Guard.”[ix]

The History of the

Mulligan Guard.

Who has not heard of the

renowned Mulligan Guard? . . . Its members are earnest, honest, enthusiastic

men, and the Guard will undoubtedly be the nucleus of a crack infantry regiment

one of these days. But even then it may

be questioned whether it will allow its name to be changed, so proud are they

of their patron, Terrence Mulligan, the Assistant Alderman of the red-hot

Seventh [Ward] . . . .

The History of the Mulligan Guard, New

York, Collin & Small, 1874.[x]

James

Mulligan, the patron of the real-life militia, was a successful farrier

(horse-shoer) and neighborhood politician who was active in Democratic and

Tammany Hall politics. He lived at 119

Grand Street in New York City, and owned an events facility at 125 Grand Street

that he rented out for meetings, dinners, and balls.

In 1854, a

watershed year in Tammany

Hall politics, he was on the Democratic ticket for School Trustee of the

Fourteenth Ward. He was also active in

Irish politics.[xi] In the mid-1840s, he was a member of the

General Committee for the “United Irish Repeal

Association”,[xii]

a political movement that supported constitutional reform in Ireland and

independence from Great Britain. In the

mid-1850s, James Mulligan served as President of the “Irish Aid Society,” a

charity benefiting poor Irish in New York City.[xiii] One of their programs granted money to people

willing to relocate to “the West . . . whose virgin soil teems with fertility,

ready to give up its golden treasures to the first efforts of industry.”

Although

James Mulligan appears to have become a successful businessman and community

leader, his earlier life involved some comic situations that would have been

right at home in a “Mulligan Guard” skit.

In 1838, Mulligan

was fined $25 and costs for throwing a bucket of water or two over Mrs. Webb’s

head after she laid out her daughter’s best petticoat to dry in front of his fireplace without permission.

He threw the petticoat out into the yard, calling the child a

“brat.” She said, “my child, sir, is no

brat, sir; you nasty good for nothing ------!”

Mulligan told her to get out of the yard, “or I’ll throw a bucket of

water on you!” She dared him; “Oh brave

blackguard, throw a pail of water on a woman!

I dare you to do it, you dirty fellow!” So he did – twice.[xiv]

The previous

year, Mr. Mulligan was in court as plaintiff when one, Edward Mahony, stole “a turnip and trimmings – a watch and its

appendages, the property of James Mulligan, No. 119 Grand street.” The defendant claimed he was only borrowing

it. A third-party testified that Mahony had

offered to trade watch-chains with him.

The verdict – “petty larceny only.”[xv]

Ed Harrigan,

who created the “Mulligan Guard” series, was born in New York City in 1844 and

would have been fourteen years old when the “James Mulligan Guard” held its meetings

in 1858. If Harrigan lived in an Irish

neighborhood in New York City, and had a passing familiarity with the social

and political scene, he may well have been aware of James Mulligan and his

“Mulligan Guards.” The “Mulligan Guard”

series could have been based on his childhood recollections of a specific or

general recollection of the real-life “James Mulligan Guard.”

Another

element of “Mulligan Guard Chowder” was also based on real life. “Chowder Parties” were a common feature of

local political, social and military life.

Chowder Parties

The “chowder

party,” a close cousin to the “clam bake,” dates to at least 1834.

In a

discussion of how best to celebrate the Fourth of July in 1834:

For our own part, we are

free to say that we like not the tumult of a city celebration, and shall seek

our pleasure in a more quiet mode; but whether it shall be by means of a

chowder party in company with “the trampers,” on Barren Island – by a family

dinner at home, or by a visit to one of the thousand beautiful spots which are

to be found upon our own island, or within fifty miles of New-York, yet remains

to be determined.

The Long-Island Star (Brooklyn), June

26, 1834, page 3.

One of the

Vanderbilts offered “Chowder Party” excursions in the 1840s:

|

| Morning Herald (New York), July 24, 1840, page 3. |

|

| Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York), August 8, 1842, page 2. |

Six decades

later, a newspaper article surveyed the history of “chowder parties” as the “Chowder

Party” season heated up in the late summer of 1900. The article describes how the “chowder party”

had become a standard feature of social, political and militia life; similar to

the fictional “Mulligan Guard Chowder” and with similarities to the real life

of James Mulligan, the patron of the real “Mulligan Guard”:

The

chowder party was originally an outing arranged by a few men, who made use of a

“day off” to fish and then have a “bite” and a drink before coming home . . . . Target shoots and picnics suffered because of

the popularity of the chowder parties, and it was only a few years after their

introduction that outing parties had to bear that name to make them attractive.

But

as they grew in size the chowder part became less important, and a chowder party for a shop association, lodge, military

company or political club now usually dispenses with clams; what it really

needs is beer.

The

men who go into politics for the purpose of securing office for themselves or

for their friends, if they live in the lower part of the city, usually have

headquarters where their friends may congregate [(as did James Mulligan)]. . . . The association bears his name,

and every winter the saloons, barber shops and little stores have a placard in

their windows on which there is a portrait of the leader and the announcement

that the Patrick McCarthy or Moses Cohen or Giovanni Peanutti Associatino will

have a “grand reception ball” at some hall in or near the district. . . .

It’s

a long time between drinks from one grand ball and reception to another, and in

order to keep himself well before his constituents and to show that he is still

“it” the leader usually selects the dog days to give his friends an outing, which has for years taken the form of a chowder

party.

New York

Tribune, September 9, 1900, Illustrated Supplement, page 1.

In testimony

before the New York Senate in 1893, Tammany Hall Democrats were grilled about

using the sales of the Seventh Ward’s “chowder party” tickets to secure

political favors, influence and positions:

“Is it not a fact that the

saloon keepers and houses of prostitution paid $5,000 for chowder tickets?”

The witness replied that the insinuation

was infamous.

Then Chairman Lexow innocently

inquired, “How much chowder was supplied a man for $5?”

and ex-Judge Ransom assured the Senator that there were many other things in

chowder parties besides chowder. That

gave Mr. Goff an opening, and he added to the prevailing merriment by remarking

that chowder parties, and even chowder,

contained as many things as are in the list of a district leader.

The Sun (New York), June 8, 1894, page

2.

Mulligan Parties

By the early

1900s, “Mulligan” came full circle.

Whereas “Mulligan,” perhaps from “Mulligan Guard Chowder,” became

“Mulligan Stew;” “Mulligan,” apparently from “Mulligan stew,” may have

occasionally replaced “chowder” in “chowder party.” Or, perhaps the expression, “Mulligan party,”

merely reflected the fact that some people organized parties around a “Mulligan

stew,” as others did around chowder.

There was a

“Mulligan party” at Pike’s Peak in 1907:

|

| The Evening Statesman (Walla Walla, Washington), February 7, 1907, page 5. |

In 1913,

Thomas Gaines was arrested for holding “mulligan parties” with stolen chickens:

|

| The Tacoma Times (Tacoma, Washington), August 16, 1913, page 1. |

A ‘Mulligan’ is a great affair.

It’s a sort of cross between a Sunday school meeting in Japan and an English

athletic meet in Berlin in 1917.

Salt Lake Telegram (Salt Lake City,

Utah), July 26, 1915, page 12.[xvi]

Conclusion

The

expression, “Mulligan stew,” may reflect a melding of “Irish stew” with

Harrigan & Hart’s “Mulligan Guard Chowder”; a chowder that the fictional

“Mulligan Guard” made with a cat. The

expression may have taken root when unemployed men organized themselves into

militia-like units – “Coxey’s Army” – for a march on Washington to protest

economic conditions and lobby for a federal jobs program. The widespread use of “Mulligan stew” in

Coxey’s army may have influenced the continued association of “Mulligan stew”

with tramps and hobos. And, the

fictional “Mulligan Guard” may have been based on the actual “Mulligan Guard”

that was active in New York City in the 1850s.

Of course, I

could be wrong; if so, I want a do-over – a “Mulligan” – but that’s a whole nuther

story.

[ii]

See, for example, “Mulligan Stew”,

Wikipedia.org (accessed June 19, 2016) and Barry Popik, “Mulligan

Stew”, The Big Apple online Etymology Dictinoary (accessed June 19, 2016).

[iv] John

Mollard, The Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined, 2d edition, London, 1802,

page 53 (Cutlets a la Irish Stew).

[v] The New York Herald, February 9, 1869,

page 7.

[vi] The New York Times Theater Reviews,

1870-1885, New York, The New York Times & Arno Press, 1975 (1879 D 21,

7:2).

[vii] “Felis”

is the genus of a type of cat and “Maniculatis” is a species of mouse..

[viii]

Edward Harrigan, The Mulligans, New

York, G. W. Dillingham Company, 1901.

[ix] The

original manifestation of the fictional “Mulligan Guard,” in 1874, was said to

have been organized by a man named Hussey, with a patron named Alderman

Terrence Mulligan. Later versions of the

“Mulligan Guard” appear to have been organized by a grocer named Dan Mulligan.

[x]

The book does not list the name of the author, but the characters and

situations appear to be at least based on Ed Harrigan’s play, as his name is

mentioned on page 1 of the book as one of the leaders of the “Mulligan Guard.”

[xi] The New York Herald, October 26, 1854,

page 1.

[xii] New York Daily Tribune, February 8,

1844, page 3.

[xiii]

The New York Herald, September 6,

1855, page 2.

[xiv] TheMorning Herald (New York), January

23, 1838, page 2.

[xv] The Morning Herald (New York), August

16, 1837, page 2.

[xvi]

Credit goes to Stephen Goransan for uncovering

the sense of “mulligan” as a party, and finding the citation from the Salt Lake Telegram, July 25, 1915, page 12.

No comments:

Post a Comment