Ride ‘im Cowboy!

Oh, the ten-gallon hat is a wonderful thing,

Both to wear on the head and to chuck in the ring

And at coming conventions let delegates sing,

Ride ‘im cowboy!

Let bold Lochivar gallop out of the West

On a bucking cayuse, with his chaps and a vest,

And a ten-gallon hat and a gun and the rest -

Ride ‘im cowboy!

“Ride ‘im Cowboy,” L. C. Davis, “Sports Salad” column, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 11, 1927, page 15.

President Calvin Coolidge and “Dakota” Clyde Jones on the steps of theWhite House in their Ten-Gallon Hats.

According to History.com, “most experts argue that the name ‘10-gallon hat’ is actually an import from south of the border,” derived either from “braided

hatbands - called ‘galons’ in Spanish,” or from “the Spanish phrase ‘tan galan’ - roughly translated as ‘very gallant’ or ‘really handsome.’”

The History.com article is wrong on at least one point - most experts do not “argue” either one of those theories,

pro or con. Most people discussing one or the other, or both of these origin stories, generally state them as fact, or state as fact that one or the other theory is true, or likely to be true, or believed by other “experts”

to be true or likely to be true. There has been very little published argument, analysis or discussion, pro or con, of either one of those theories, since their first appearances in print many decades ago.

The History.com article may also be wrong about the likely origins of the expression “ten-gallon hat.” A third,

simpler theory seems more likely - that “ten-gallon” is an “irreverent,” humorous exaggeration used to emphasize the relatively large size of the hat. The editors of the Merriam-Webster dictionary supported the exaggerated-volume theory in a syndicated column in 1987. The same column dismissed the braided hatband theory as “unlikely.”

The likeliest and most obvious explanation for the word’s being used in this way is that the hat, like the gallon measurement, was large, perhaps the largest hat in the West. Just

as the word “pint” is often used to describe what is smaller than average (as in “pint-sized” and “half-pint”), the word “gallon” came to signify what is larger than average,

even enormous.

“Take Our Word” (syndicated column), the editors of Merriam-Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, Montana Standard (Butte, Montana), February 1, 1987, page 22.

The exaggerated-volume theory is also consistent with the earlier use of “x-gallon” to describe a different style of large hat. For many decades, beginning as early as the

1880s, silk top hats, stovepipe hats or plug hats, were routinely referred to as “two-gallon,” “four-gallon,” “five-gallon” or, on occasion, even “ten-gallon” hats, although

by far the most common version seems to have been the “two-gallon” hat.

Beginning in the late-1910s, as top hats were going out of style, western-style “cowboy” hats became the new sheriff of “x-gallon” hat town. One of the earliest

known, unambiguously Western examples was a reference to “ten-gallon hats” in Texas, although “two-gallon” and four-gallon” were more common through much of the 1920s. References to “x-gallon”

western hats were kept in the public eye through movies and movie commentary, shameless self-promotion by westerners and western towns and civic organizations, and by several high-profile incidents involving Presidents Harding

and Coolidge and high-profile hats. “Ten gallon hat” would become more-or-less standard by the 1930s.

Given the long history of “x-gallon” in reference to non-western-style hats, decades before its use with respect to western-style “cowboy” hats, it seems unlikely

that the “gallon” in “x-gallon” hat was derived, originally, from the Spanish “galon” braid said to have been used on Mexican sombreros. And given the long history of “x-gallon hat”

decades before “ten gallon hat” became a thing, it seems unlikely that “ten-gallon hat” was derived, in the first instance, from the Spanish compliment, “tan galan.”

Two-Gallon (or more) Top Hats

Many of the early examples of “x-gallon” hat in print do not specify or explain the hat style at issue. But the context of several examples suggests, and some later examples

specifically clarify, that the types of hats generally referred to in that fashion are formal, silk top hats, or stovepipe hats, of the style associated with Abraham Lincoln or the Monopoly board game mascot, rich Uncle Pennybags.

A tall hat suggests a large volume, which was humorously referred to as an “x-gallon hat.”

The earliest such reference, from 1882, does not specify the type of hat, but suggests that it would make the speaker unrecognizable from his normal appearance.

Hush! Charley; don’t talk so loud. When we have our two-gallon hat on the girls can’t tell us from the “hairy man of the jungles.”

The Homer Index (Homer, Michigan), April 12, 1882, page 3.

Another early reference does not mention the type of hat. But it appears in a story about a big-city businessman, “a fellow from Pittsburgh,” who had been putting on airs and

treating the locals rudely while visiting the smaller town of Monongahela; precisely the kind of person who might be more likely to wear a formal hat than the rustic locals. But he was put in his place by a school girl.

Standing at the City Hotel door, with a two-gallon hat on, he ogled a school girl passing down, with an insolent air, and said:

“Good evening, Miss.”

“Good evening,” she replied, looking at him so suspiciously that he hesitated.

“Ahem, Miss, ahem, a-“

“Well,” she put in, “why don’t you bark?”

“Bark! bark! What do you mean? I don’t quite understand.”

“Oh, you don’t? Why, here in Monongahela a puppy that has had any decent training always barks when he sees a stranger.”

The Daily Republican (Monongahela, Pennsylvania), April 16, 1883, page 4.

Another early example does not describe the hat, but it takes place at a wedding, precisely the sort of place a formal hat might be worn.

A number of Pittsburg’s darkest and handsomest African citizens, the girls full of fun, and the boys with two gallon hats on, went up on the morning train to attend the wedding of two of Brownsville’s darkest and handsomest . . . .

The Daily Republican (Monongahela, Pennsylvania), May 24, 1883, page 4.

Another early example involved a political club from Pittsburgh’s Continental Club, “with their big crimson banner and two-gallon hats,”i

attending Grover Cleveland’s Presidential inauguration; precisely the sort of event where a silk top hat might have been worn at that time.

An early example from Michigan may be the oldest version of the “old chestnut”ii about a large hat covering a small brain.

The young Paw Paw plug thinks it requires a two gallon hat to cover a pint of brains.

The True Northerner (Paw Paw, Michigan), September 2, 1886, page 5.

Another early “x-gallon” hat joke relates to “dudes” wearing “plug hats.” Merriam-Webster defines “plug hat” as “a man’s stiff hat (such as a bowler or top hat).” At the time, “dudes” were generally high-society

types (or wannabe high-society types); in other words, precisely the sorts of people who might wear a top hat.

Four-gallon plug hats have had squally times during the April winds. The old and younger dudes are expecting calmer times this month.

Des Moines Register, May 4, 1888, page 5.

A report out of Richmond, Indiana in 1891 also associated the “x-gallon hat” with dudes.

He was no dude. He didn’t carry a cane nor sport a two gallon hat, his coat was somewhat worn and his shoes were a little run down at the heel. . . .

The Richmond Item (Indiana), July 18, 1891, page 4.

On occasion, the nominal volume of the hat might be larger than the standard two gallons. That same year, a salesman visiting Bancroft, Michigan was described as an “elderly man

with silvery hair and whiskers, covered up with a five gallon hat.”iii

And in 1892, a (presumably) high class reporter visited a low-life “unmasked ball” of the “lower ten” percent of society (he was visiting in the role of reporter,

he reassures his readers). In his report of the affair, he recounts an exchange between two regular attendees eyeing the fish-out-of-water reporter and wondering what he was doing there.

“Say, Jen, whose de bloke wid de four gallon hat?”

The interrogator was a decidedly uninviting character. Jen, the girl at his side, was just as tough.

“Oh, he’s one of dem reporters wot tinks he knows it all; how I’d like to swot him one in de jaw,” she replied.

The Parsons Daily Sun (Parsons, Kansas), January 6, 1892, page 2.

Later examples are more clear about the type of hat referred to by the expression, “x-gallon hat.”

The plug hat is rather an uncommon sight nowadays in this part of the country, but one is occasionally seen on the streets and never fails to excite comment. The small boys, and some of

the larger ones, have an almost uncontrollable desire to take a shot at it with a snowball. The wearer of the “begum” or “two gallon” hat is generally supposed to be a person of distinction, either a congressman or hackdriver, and it is very wrong for the boys to throw snowballs at his hat

- and miss it.

The Courier (Fairview, Kansas), January 31, 1896, page 1.

The earliest-known example of “ten gallon hat” is from a political parade in 1908, by the Blaine Club of Cincinnati. The article does not describe the style of hat, but a contemporaneous

photograph of the same event proves, at least in this instance, that the hats being referred to were of the top hat style.

This morning, just about the time Enquirer readers pick up the paper and give it hasty perusal before negotiating their ham and eggs and hot rolls, a special train that worked overtime in

eating up the distance between this city and the town of the Big Wind on Michigan’s shores will be shedding oodles of white ten-gallon hats in the Union Depot of the latter city.

Cincinnati Enquirer, June 15, 1908, page 7.

When the Blaine club, of Cincinnati, marched up to the Auditorium in Chicago Tuesday it brought back to the minds of old-timers the days of a quarter century ago, when political clubs were

uniformed. The Blaine club wore the high white hats which were so popular during the campaign of the eighties.

Detroit Free Press, June 17, 1908, page 6.

Numerous examples of “x-gallon hat” from the same period are suggestive of its being a piece of formal wear, and not informal, western attire. The hat King George wore before

his coronation, an “ordinary black silk beaver,” was said to have a “capacity about two gallons.”iv A “long tail coat, five gallon

hat, or a few lapel trinkets, winks and passwords” were said to have once been all that was necessary for “admission into the best” society.v

And when former Mayor John F. Fitzgerald (John F. Kennedy’s grandfather) led the Boston Braves onto the field for game four of the 1914 World Series, he was “without his two-gallon hat and cutaway for the first

time. A soft hat and business suit sufficed.”vi They would lose the game and the series that day. Blame it on the hat.

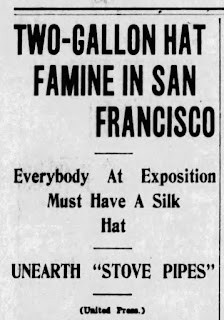

And when representatives of industry and domestic and foreign governmental delegations descended on San Francisco for the Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915, the increased demand for silk

“stove pipe” hats created a “two-gallon hat famine.”

There’s a two-gallon hat famine in San Francisco. The suffering is terrible. Peaceful old patriarchs are being dragged forth to

brave the winds and fogs to make an Exposition holiday. “Tiles” of by-gone days are being forced to desert dusty corners sacred to the memories of ancestors, and silk hats even of the Days of ’49 - more relics of the past - are serving in proud processions of Twentieth Century progress.

Ask any hat man in San Francisco and he will tell you that attempting to serve the Panama Pacific Exposition with silk hats is as bad as furnishing Europe with munitions. . . more two-gallon

hats are being used at the Exposition than were required to inaugurate all the Presidents and Governors of these States. The reserves of 1916 were long ago called out and the “home defense” is now on its last

legs.

It’s this way; every time a Governor, General, former President or somebody of that sort arrives in town to visit the Exposition, several committees doll up to meet them. Everybody must have a silk hat. There are is a constant succession of these visits, which cause considerable wear and tear on the hats, and in addition every twenty-four hours at the

Exposition is somebody’s or something’s “Day.”

Evening Sun (Hanover, Pennsylvania), August 13, 1915, page 6.

The “famine” in San Francisco was as much a matter of limited supply as it was of high demand. Silk hats were going out of style. An obituary for the out-of-fashion “Stovepipe”

hat appeared in a 1913 issue of Harper’s Weekly. It explicitly included “x-gallon hat” as on of several alternate names for the silk, cylindrical

hat.

The Rise of the “Stovepipe”

The shiny silk cylindrical hat, sometimes called topper, high hat, plug, high dicer, stove-pipe, or four-gallon hat, by the irreverent, seems fated to disappear, after little more than one century of existence.

Harper’s Weekly, Volume 57, Number 2940, April 26, 1913, page 26 (later reprinted in numerous newspapers in the United

States and Canada).

Since nature abhors a vacuum, with one “x-gallon” hat on its way out, another one was on its way in. Western “cowboy” hats would soon replace the top hat as the

“x-gallon” hat of choice.

And just a few years later, Eastern “dudes,” who in an earlier decade might have worn a “two gallon” stovepipe hat, were now donning “two-gallon” cowboy

hats at Western “dude ranches.”

It is odd how the atmosphere of the cow-country can in a few days transform a dapper college sophomore or a tired cabinet-minister into a swashbuckling Western character, arrayed in a “two-gallon”

hat, a flannel shirt of clamorous pattern, and nondescript trousers tucked into fancy, high-heeled boots with huge, jingling spurs. It is odd how this creature, born to ride in town-cars and elevators, will take to riding

cow-ponies, and seek to imitate, in speech and manner, the lowliest wrangler who looks after the dude’s horses.

“Westward-Whoa!” Gene Markey, Harper’s Bazaar, July 1924, page 44.

A “lady dude” in a “two-gallon” hat, Harper’s Bazaar, July 1924, page 44.

Ten-Gallon (or less) Cowboy Hats

The earliest example I’ve found of “x-gallon hat,” unambiguously in reference to a western-style hat, is from 1917. A man named F. T. Boylston, of the IXL ranch in Wyoming,

took a job inspecting horses at the Kansas City stock yards. But he was something of a heavy drinker, “he had a thirst eleven months long,” and needed some cash. To alleviate his situation, he passed a bad check

- he got away with it because of his big Stetson hat.

INDORSED BY A 6-GALLON HAT.

Or, Why a Farmer Cashed a Bad Check for a Cowpuncher.

. . . Boylston was arrested yesterday on complaint of Elliott. He gave Elliott $10 of $15.95 he had left, and promised to pay back the rest in two weeks.

“If it hadn’t been for that big cowboy hat,” Elliott mused, “I wouldn’t have cashed the check. After this whenever I see a ‘Stet’ I’m going

to run.”

The Kansas City Times, February 15, 1917, page 7.

A Texas reporter chastised another reporter for confusing “Dutch” people from the Netherlands with “Dutch” Germans. A New Yorker might make a similarly “provincial”

error in assumptions about Texans.

That is as provincial an error as for the New Yorker to assume that the Texan always wears a ten gallon hat, and spends all his time lynching people.

El Paso Herald, January 5, 1918, page 4.

And again in El Paso, and again a “ten gallon” hat.

“El Paso’s streets are the most fascinating that I have seen in some time,” said Mrs. E. B. Wentworth, “for wherever I go I see such a diversity of interest, such

a variety of color. Here is the cowboy, with his long boots, his ten gallon hat, and his colorful personality with those far-seeing eyes of the man who dwells on the desert

and sees afar off; here is the Mexican, with his strange garments, his face half hidden with his neck scarf, and just beyond a young girl steps out of a store, clad in garments and dressed with the style which might be expected

of New York city itself. From quaint, dirty, and yet picturesque Chihuahuita to the exclusive homes in Austin Terrace, this city just radiates charm.”

El Paso Herald, January 15, 1918, page 6.

Cowboys from the west Texas hinterlands wore “ten gallon hats” when they went to enlist in the “American liberty army” in World War I.

El Paso, Tex., Jan 23. - High heeled cowboy boots chaps and “ten gallon hats” have replaced shoes of English lasts, pinch back suits and golf caps as the wearing apparel of the majority of recruits who are accepted at the local army recruiting station for service in the American

liberty army.

The rush of the city boys and young men to join the colors is almost over, according to the officer in charge of the station. But the news that the United States needed her young men has

just begun to percolate to the isolated cow camps, ranches and mining districts of the southwest. The result was a rush of applicants for enlistment from these sparsely settled districts of the southwest.

Grand Forks Herald (Grand Forks, North Dakota), January 23, 1918, page 2.

Sheriff Joe Adair, of Atoka County, Oklahoma, wore “what he calls his ‘five-gallon sombrero’” on an extradition trip to St. Joseph, Missouri.vii Frank Benjamin, of El Paso, Texas,

wore a “five-gallon hat” when he insulted Freddie Harris, of Riverside, California, by calling him an “orange picking kid.”viii

And the oil boom in Texas created a jumble of disparate clothing styles, “a chaotic clashing of costumes - overalls and tailored business suits, Broadway derbies and high-crowned Texas ‘five-gallon Stetsons.’”ix And the Governor of Texas wore a “‘five gallon’ cowboy hat”

during a trip across the state.

Governor Hobby on the trip wore a “five gallon” cowboy hat and a vivid red shirt, presented to him by his admirers in Van Horn prior to his departure.

El Paso Times, August 30, 1919, page 2.

When “Miss Wyoming,” Helen Bonham, visited New York City in 1920, for the purpose of promoting a “Frontier Days” round-up in Cheyenne, she wore a “two-gallon”

Stetson hat.

She was entertained at the McAlpin by General Coleman du Pont, to whom she had a message, and she insisted that the financier try on her “two-gallon” Stetson.

New York Tribune, July 4, 1920, section 7, page 5.

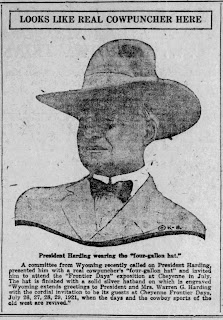

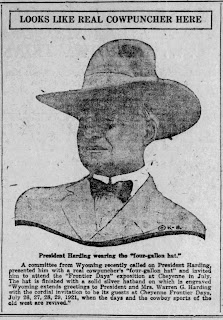

She returned to the East Coast the following year, this time with a widely-reported “four-gallon” Stetson sombrero, a gift for President Harding.

A “four-gallon” Stetson sombrero with an engraved invitation on a chased silver band is Cheyenne, Wyoming’s, way of asking Mr. Harding to witness the forthcoming annual

“Frontier Day” riding and roping contests there. No direct suggestion that he wear the unique “skypiece” at the roundup is conveyed, but “Miss Wyoming,” who is putting the finishing touches,

appears hopeful.

Brooklyn Standard Union, June 22, 1921, page 16.

“Four-Gallon” Hat for President Harding.

This beautiful Stetson bears a heavily chased silver band, tied with a cinch knot of white doeskin. On the band is engraved an invitation for the President to visit the annual Frontier Day.

“Miss Wyoming” and Governor Carey are admiring the hat.

Boston Post, June 22, 1921, page 17.

President Harding wearing the “four-gallon hat.”

The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), July 18, 1921, page 4.

A story out of Montana involving a Chinese Tong gunman in a “two-gallon” hat reads like an episode of the classic TV show, Kung Fu, starring David Caradine as Kwai Chang Caine.

“The Cowboy,” Tong Gunman, was in Helena After Butte Outbreak

“The Cowboy,” so called because of his partiality to a two-gallon Stetson hat and other characteristics of his attire copied after range-riders, and said to be greatly feared by Chinese because of his reputation as a Bing Kong Tong gunman, who is being sought by the authorities at Butte

in connection with the murder of Hum Mon Sin, a member of the Hop Sings, was in Helena a short time following the outbreak in the mining camp, it was said yesterday.

The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana), March 4, 1922, page 10.

Although two, four and ten seem to have been the more common values, the nominal volume of cowboy hats were all over the map, anywhere from one to ten. A headline ahead of Casper, Wyoming’s

Rodeo Week in 1923 announced, “Gallon Hats in Vogue as Rodeo Opens.”x When the Texas sheriffs held

their annual convention in Galveston in 1923, they wore “big three-gallon Stetson hats - famous because Texas sheriffs made them so.”xi An “old timer” sitting on a fence at the Muskogee, Oklahoma race track in 1922,

wearing a “six gallon stetson turned down fore and aft, and turned up, starboard and port.”xii

And in Montana, the residents of Shelby were expected to “start wearing their eight-gallon Stetsons and other cowboy regalia” when the roundup and rodeo came to town in the summer of 1923.xiii

In 1923, civic leaders in Forth Worth, Texas staged a “Dress Up Day” for the city’s Diamond Jubilee, in which celebrants were encouraged to wear their “five gallon

hats.”

True to the Jubilee spirit, it is likely that all Fort Worth will don the garb of the Jubilee celebrator, including five-gallon hat, red shirt and boots, while the women folk will appear

in the garb of their ancestors of fifty or seventy-five years ago.

Fort Worth Record-Telegram, November 1, 1923, page 7.

Civic leaders also formed the “mystic order of the sons and daughters of the Saxet” (Saxet is Texas, backwards) to promote the city’s Diamond Jubilee. Madame Olga Petrova,

in town to perform during the Jubilee, paid her $1 membership fee and posed in a “four gallon sombrero.”xiv The “King Saxet” wore a complete cowboy ensemble.

Fort Worth Record-Telegram, November 1, 1923, page 7.

When Fort Worth was set to host the Southwestern Exposition and Fat Stock Show the following summer, the “mystic order of the Saxet” took the lead in encouraging locals to “bring

out the four-gallon hats” for the duration of the exposition. Hubb Diggs, the “King Saxet,” even issued a “four-gallon hat decree.”

The royal attire of the Sons and Daughters of Saxet will consist of the big cowboy hat circled with the official Saxet band.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 2, 1924, page 14.

A clothing store in Oklahoma advertised Stetsons “of the ‘four gallon’ capacity” to stockmen and visitors to a livestock show in 1924.

Oklahoma Daily Live Stock News (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma), March 4, 1924, page 4.

Civic leaders in Butte, Montana organized something called “The Montana Order of Ten-Gallon Stetsons.”

Independent-Observer (Conrad, Montana), July 16, 1925, page 6.

With actual Westerners pumping up the volume with four, five and ten gallon hats, the entertainment industry magazine, Billboard, clung to the original “two-gallon” hat expression, which had until recently been regularly used to refer to a different style of hat.

Miss “Wild West” showed off her “two-gallon” hat (and priceless legs) when she arrived in New York City to join Ziegfeld’s “Follies,” with a recommendation

from a tent show operator in Shelby, Montana.

At Grand Central Station, Miss Salmon, clad in a two-gallon hat and a cowhide skirt, mounted a six-cylinder broncho and was taken to the Ritz-Carlton, there to remove the Pullman dust before having a chance to exercise her gills before the beauty chorus magnate.

Billboard, August 18, 1923, page 8.

The Mayor of San Francisco was inducted into the “Order of the ‘two-gallon hat.’”

Mayor Rolph, of San Francisco, is crowned with the official headpiece of the Pony Express Celebration which is to be held in the Golden Gate City September 9.

Billboard, August 18, 1923, page 8.

Organizers of the Calgary Stampede posed in their “two-gallon” hats.

On the left above (under the “two-gallon” hat) is Guy Weadick who most successfully staged the Stampede in connection with the recent Calgary Exhibition, and whose ranch is near that of the Prince of Wales.

Billboard, September 8, 1923, page 96.

And the famous rodeo cowboy (and later the recipient of an honorary Oscarxv), Yakima Canutt, was said to be able to increase the size

of his “two-gallon” hat by one gallon, after winning the title of “all-round cowboy” at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup.

Yakima Canutt, of the State of Washington, may now increase the size of his “two-gallon” hat by one gallon, for he had won the title of champion all-round cowboy at the Pendleton

(Ore.) Roundup.

Billboard, October 20, 1923, page 85.

The transition of x-gallon top hats to x-gallon cowboy hats may have been nearly complete in 1926, when a movie fan-magazine published a headshot of the movie actor, Huntly Gordon, in a

cowboy hat with a six-shooter. They referred to his hat as a “two-gallon” hat, as opposed to a “silk topper,” with no apparent irony about the juxtaposition of the different hat styles and their recently

reversed volumetric designations.

HUNTLY GORDON

He’s never had the opportunity to tear loose in an outdoor picture for his assignments have invariably been society roles. However, there is nothing to keep huntly from wearing a bandanna

handkerchief instead of a bat-wing collar, a two-gallon hat instead of a silk topper, and fanning a six-shooter thru the air when he wants to look like a true son of the wide open spaces.

Motion Picture Classic, Volume 23, Number 6, August 1926, page 12.

The transition from any-old-x-gallon hat, to “ten gallon hat,” may have been influenced by widespread press coverage of President Coolidge and his “ten gallon hats”

- he wore them during a visit to South Dakota, and again later, when one of his South Dakota companions repaid the visit with a trip to Washington DC, and later still, during a fishing trip to Wisconsin. But Coolidge’s

first run-ins with large cowboy-style hats were not of his own volition, and not all of the same volume.

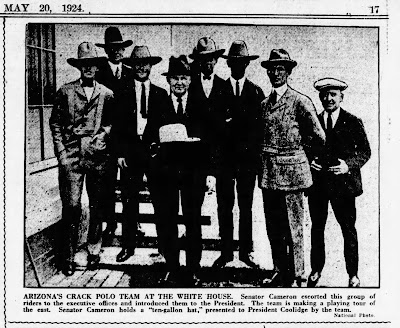

In 1924, a “crack polo” team, visiting Washington DC from Arizona, presented the President with a “ten-gallon hat.”

Senator Cameron holds a “ten-gallon hat,” presented to President Coolidge by the team.

Evening Star (Washington DC), May 20, 1924, page 17.

President Coolidge famously refused to pose in a “four-gallon” hat, in a publicity stunt to promote a new film staring the movie cowboy, Tom Mix.

After receiving the rough riding actor the President with a sigh agreed to step outside and be “shot.” The camera men were lined up like a true enough firing squad. There were

efforts to get the President to put on a four-gallon hat. That was too much. Mr. Coolidge couldn’t imagine himself as a cowboy. So the picture was shot with the

President and the actor and its appearance coincided with the “release” of a new feature by the self-same star.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 4, 1925, page 19.

Pres. & Mrs. Coolidge & Tom & Mrs. Mix, 5/21/25. , 1925. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016839894/.

Tom Mix was likely promoting The Rainbow Trail (a sequel to Riders of the Purple Sage), which had just started showing in movie theaters a week earlier.

Exhibitor’s Herald, Volume 21, Number 2, April 4, 1925, page 5.

Coolidge would eventually lose his fear of ten-gallon hats - and of publicity, at least as it pertained to his own hat and his own publicity. During the summer of 1927, he was seen, photographed

and filmed wearing a large cowboy hat on numerous occasions. Thousands of accounts in hundreds of newspapers across the United States reported the wearing of his “ten-gallon” hat.xvi

Charlotte Observer (North Carolina), June 27, 1927, page 5.

The President received a complete cowboy outfit for his birthday, which was on the Fourth of July.

President Coolidge was given a complete cowboy outfit today on his fifty-fifth birthday and he brought delight to his guests and boy scouts who presented the outfit by appearing on the front

lawn of the state game lodge in the full regalia of a western horseman.

The hills surrounding the lodge resounded with cheers as the President returned from the house in the middle of his birthday party wearing a bright red shirt, blue kerchief, chaps, boots,

spurs and a ten gallon hat.

Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia), July 5, 1927, page 1.

President Coolidge in cowboy outfit, standing in field with photographers; mountain in background. , ca. 1927. July 12. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/96522723/.

Not everyone was impressed.

The rumblings that you may have heard lately were the rumblings and nashing of teeth of Teddy Roosevelt when he turned over in his grave at the thought of the little slim Cal at a rodeo wearing a ten-gallon hat and sheepskin breeches. The Pathe News on the films in the cities showed Cal donning his wildwest outfit and a pinto pony being led out to him.

The Daily Standard (Sikeston, Missouri), July 22, page 2.

At the time, there was speculation in the press that Coolidge would seek a third term as President, and his western wear was thought to be an effort to curry favor among voters in certain

parts of the country.

The Daily Standard (Sikeston, Missouri), July 22, page 2.

President Coolidge wore a “ten gallon” hat to a rodeo, where he cheered on his “favorite entry,” a man named Dakota Clyde Jones, described variously as the man “in

charge of the Custer State Park rangers” or the “keeper of the horses at the summer white house.”

From the center of a mammoth crowd of westerners, President Coolidge, wearing a “Ten-Gallon” hat, today watched the tri-state round-up, a spectacle of skill and daring on horse and steer.

The Atlanta Constitution, July 6, 1927, page 10.

And he wore a “ten-gallon” hat to the ground-breaking (or would it be rock-breaking) ceremonies for Mount Rushmore, which he attended in August 1927.

When President Coolidge attended the Mt. Rushmore Memorial Celebration near his South Dakota summer home, he chose to go astride “Mistletoe” his favorite horse, to wear his new ten-gallon hat and good substantial cowboy riding boots. “Quite Sensible,” said Dakotans.

The McCook Tribune (McCook, Nebraska), August 24, 1927, page 3.

President Coolidge broke out his “ten-gallon” hat again in October, when his favorite South Dakota cowboy, “Dakota” Clyde Jones, visited Washington DC.

The cowboy wore his ten-gallon hat and high-heeled riding boots but parked his roweled spurs and chaps outside lest they scratch the White House furniture. . . .

The president took one of his own ten-gallon hats out of camphor this afternoon, donned it and posed with Jones for photographers on the south lawn of the White House.

The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania), October 22, 1927, page 1.

At least one observer credited the President with reviving interest in the “ten-gallon” hat.

If the pilgrimage to the Black Hills has done nothing else it has served to bring the ten-gallon hat back to its own.

Most folks had forgotten that there was such a thing - that is, most city folks. The big hat, so far as the great bulk of the population knew, has gone into that musty limbo from which there

is no return.

But the ten-gallon hat has staged a comeback. Athwart a presidential dome it has been shot for the movies and recorded indelibly by the still shots. The ten-gallon hat - there she, or he

- stands and long may it wave.

The ten-gallon hat is in the ring and a hat of that kind makes mighty near a ring full without any other company.

The Butler County Press (Hamilton, Ohio), August 5, 1927, page 3.

But President Coolidge was not done wearing his ten-gallon hat. During the summer of 1928, even without the hint of a possible campaign in the offing, the President shocked locals in Wisconsin

by breaking out his “ten-gallon” hat to go fishing.

First definite accounts of President Coolidge fishing - picturing him as wearing a ten-gallon hat, rubber boots and a slicker over a khaki shirt and using dry flies as his bait - both puzzled

and delighted this town [(Superior, Wisconsin)] of ardent fishermen today.

Mr. Coolidge’s ten-gallon felt hat gave rise to the puzzlement, while the news that he did not use worms for bait caused much relief among the easily touched sporting sensibilities

of the habitual trout anglers.

The Lexington Herald (Kentucky), June 22, 1928, page 1.

Although the hyperbolic “ten-gallon” label stuck, some widely circulated jokes addressed the literal truth of the hat-size, the truth about Coolidge and the truth about how

many Westerners actually wear the hats.

An anxious inquirer asks The Journal if a “ten-gallon hat” really holds ten gallons. Darned if we know. We never saw one in South Dakota till Coolidge came West. - Western (S.

D.) Journal.

The News Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), August 25, 1927, page 18.

The present occupant of the White House brings in his fish and poses with them the while his neck is encircled in a high, stiff collar. The country saw at once that it wasn’t merely

a matter of being out of tune with fishdom in the matter of bait - the whole thing went deeper than that and was in reality a matter of disposition, or temperament, or something like that. But even that wasn’t as bad

as the pose in the ten-gallon hat, as it has come to be called, though it doesn’t begin to hold ten gallons. Six quarts is the usual rated capacity.

The Butler County Press (Hamilton, Ohio), August 5, 1927, page 3.

As for why the so-called cowboy hat came to be called “x-gallon,” or ultimately “ten gallon,” it seems likely that it was simply a humorously exaggerated description

of a unusually large hat style. A previous style of hat had been known by a similar name, though usually with a smaller, stated volume, and that expression seems to have been transferred from one style to another as fashions

changed.

The simple, perhaps more likely answer is not the only answer out there. There are at least two alternate theories, although neither one of them has been supported by anything other than

conjecture - in both cases, perhaps reasonable conjecture deserving of a closer look, but conjecture nonetheless - without (apparently) much effort to justify or support the theory with actual supporting documentation.

“Galon” - Braid

The theory, that the “gallon” in “ten-gallon” hat is a corruption of “galon,” a Spanish name for a decorative braid, first appeared in print in 1939.

The theory appeared in a brief article, in an academic journal, written by Arthur L. Campa, a professor of Spanish at the University of New Mexico. The article was reprinted, nearly in full, in several newspapers shortly

afterward. The theory received a gloss of extra-respectability, when cited in a footnote of a discussion on Spanish loan-words in H. L. Mencken’s American Language: Supplement I (1945).xvii It has since been repeated as fact dozens of times in dozens of

newspapers, books and other sources, generally without question, attribution or additional supporting documentation. And many of the later restatements of the theory toss in new, additional, unsupported details, not in the

original.

The theory was first published more than ten years after President Coolidge’s famous “ten-gallon” hat-wearing incidents, more than two decades after the earliest-known

examples of “x-gallon” western-style hat appeared in print, and long after the original “two-gallon” stovepipe hat had largely disappeared. The theory may have taken hold because of collective amnesia

about the archaic term for the archaic hat. And the person who first floated the theory may not have even been familiar with the passe term for the passe hat-style.

Arthur L. Campa was a Spanish language educator and pioneer in the study of Mexican-American folklore. He earned a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree from the University of New

Mexico, and a PhD from Columbia University. He authored several textbooks for people learning Spanish, several collections of North American, Spanish-language poetry, songs and stories, and a history and survey of the Hispanic

culture of the American Southwest. He spent a decade on the faculty of the University of New Mexico, served as an officer in the Army Air Corps during World War II, with service in North Africa and Italy, and later served

on the faculty of the University of Denver, as well as spending a decade as “Cultural Attache” at the American embassy in Lima, Peru.xviii

Campa was born in Mexico, to a Mexican Methodist minister who had trained in the United States and an American mother. He lived at various times in La Paz, Mexico, Douglas, Arizona and

Cananea, Sonora. His father, a captain in revolutionary forces under Venustiano Carranza, was killed in 1914, by revolutionaries under Pancho Villa. Following his father’s death, his mother returned to the United States,

moving to El Paso, and later Albuquerque, when Arthur was eighteen years old.

Arthur L. Campa graduated from Harwood Methodist High School in Albuquerque in 1923, having played on the state championship runner-up, Harwood High basketball team, during his senior year.

If Campa and his teammates had actually won the state title, it would have been another Hoosiers moment.

The Harwood boy’s school was a Methodist boarding school; a short-lived sister school (brother school?) of the Harwood Girls School, which operated for nearly a century, from the

1880s through the 1970s.xix It opened in 1922 for the “industrial and religious training of native boys,”xx

and closed in 1929, having provided for the “education of boys of Spanish descent and of Mexican parentage,” for students drawn from New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and Mexico.xxi

Following high school, Campa attended Albuquerque Business College in 1924, where he joined four of his high school teammates on that school’s basketball team.xxii

He and his brother later studied at the University of New Mexico, although there’s no indication that they ever played basketball for the Lobos, although is brother David, who had been a starter for the Harwood High

state runner-up team, won an award for writing the “best rally song” for the school.xxiii

Arthur L. Campa’s speculation about the origin of the expression “Ten-Gallon hat” (as applied to a western-style “cowboy” hat) appeared in an article entitled,

“Ten-Gallon hats,” in the journal, American Speech, in October 1939. The article was reprinted in full, with attribution, in numerous American newspapers

shortly after publication.

The original article covered half-a-page, with four paragraphs, no footnotes, endnotes, citations, or references, and no examples of early, related transitional examples. The basic thesis

is that the word “gallon” in the expression “ten-gallon hat,” was originally a “mistaken translation of a Spanish word.”

The word ‘gallon’ had no reference to size at one time; it simply served to describe the braid with which a vaquero’s hat was trimmed, and instead of being ‘gallon’

it should have been ‘galloon.’ The Mexican vaquero and charro still speaks of his sombrero galon or his galon y toquilla. In numerous ballads collected in the Southwest, the name galon appears repeatedly to describe

a ‘gallooned hat.’

Since the Spanish word galon may be translated into either ‘galloon,’ or ‘gallon’ it is not surprising that the transliteration should take that form which was closer

to the original galon. The additional descriptive ‘ten’ was simply a relative term used to designate a hat of greater size. It may not be too far fetched to note, in this connection, that the largest milkcan

used on ranches is of ten-gallon capacity.

A. L. Campa University of Mexico

“Ten Gallon Hats,” A. L. Campa (University of Mexico), American Speech, Volume 14, Number 3, October 1929, page 201.

Since its first appearance, the general idea has been repeated hundreds of times as fact, and with additional embellishments not mentioned in the original. Whereas Campa simply suggested

that “gallon” came from “galon,” and the “ten” was added to suggest relative size, later versions of the theory suggest that “ten” related to either the height of the crown,

or width of the brim, as measured by the number of “galon” braids it could accommodate. These embellishments, which are no fault of Campa’s, seem particularly implausible.

As for Campa’s suggestion that “gallon” came from “galon,” it seems as though it would have been a plausible explanation, or at least a suggestion worthy of

additional exploration, if not for the existence of the long history of describing abnormally large hats by increasingly exaggerated volume.

To fully understand the suggestion, it may be worth looking into what a “galon” is and its relationship to hats. It may be true that “galon” was a Spanish word,

but it was also a word commonly used in English-language discussion of fashion.

A “galon,” or frequently “galloon,” was a decorative ribbon, band or braid, generally with some metallic component. Many references to “galon” or “galloon”

refer to silver or gold “galon” or “galloon.”

Although most references to silver or gold galon or galloon refer to decorative trim on women’s dresses, they were also used on hats, frequently women’s hats, and not limited

to a specific style of hat.

Many “gallooned” hats, or hats with “galon” or “galloon” trim, were women’s hats.

Cream-colored straw hats have bands of gold or silver galloon with clusters of white ostrich tips and fancy jeweled pins as ornaments.

Evening Journal (Vineland, New Jersey), September 6, 1890, page 4.

A Winter Hat.

The crown of the hat is simply encircled with dull gold galon.

West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser (Truro, England), December 31, 1903, page 12.

One of the girls had made for herself a gorgeous hat band. It was of gold galloon and it had hand-made flowers, and vines running over it and caught into the gold mesh of the galloon was a kind of simulated fruit.

Los Angeles Times, October 19, 1911, page 23.

The sheaf of plumage is arranged at the top of the brim under a long, flat bow of galon.

New Tribune (Tacoma, Washington), October 23, 1914, page 15.

Of gray velvet is a scalloped-shell brimmed hat. A band of gun-metal galloon finds its way around the crown under a velvet box pleating and terminates into a brush of skunk fur partially encircling the crown.

The Fargo Forum and Daily Republican (North Dakota), September 27, 1916, Fashion Section page 5.

On the lower left is shown a mourning toque, having a dome crown and drooping mushroom brim. The trimming of this chic toque is jet beads and dull jet galloon.

The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer (Connecticut), February 17, 1915, page 9.

Se predice que se llevaran mucho los sombreros de estilo Mandarin, o seanse de ala caida; en efecto ellos son artisticos y bonitos.

Un lindo modelo de estos es de terciopelo beige cubierto con un galon de plata, y alrededor de la copa una tira de piel pasada por unas aplicaciones de plata.

El Paso Times, November 11, 1916, page 4.

A few gallooned hats were men’s hats, particularly military hats worn by high-ranking officers.

Details gleaned from a late-18th century diary, written by an early, Spanish Governor of California named Don Pedro Fages

and rediscovered in the early-20th century, were widely published in 1913. One item mentioned in many of those reports was a description of a Captain Palma’s

hat, variously described in translation as a “silver-gallooned hat” or a peaked hat, “gallooned with silver and adorned with a cockade.” The date of the writing was nearly a century before the hat-style

later associated with the expression, “ten-gallon hat” was in use, so it is unlikely that it would have been a reference to such a hat.

Also, in more recent times, a British admiral is said to have worn a “gallooned” hat.xxiv

Wearing the gallooned cocked-hat of a full admiral of His Majesty’s Navy, Sir Charles Gordon Ramsey reluctantly pulled down his flag which had flown over the naval base at Rosyth, Scotland,

and went into retirement on October 1 of last year.

Carbon Chronicle (Carbon, Alberta), May 6, 1943, page 4.

It may be true, as Arthur Campa claimed, that “galon” was used sombreros in Spanish-language writings. It is not clear, however, whether those examples were limited to fancy

hats, trimmed in gold or silver braid, or related to working hats, of the style commonly worn by Mexican vaqueros and western cowboys. He did not list any citations, so it is impossible to say.

Cowboys did wear hats with hatbands, but perhaps not generally with decorative galon. Mexicans of means did wear expensive hats, decorated with what may be described as metallic galon,

but it is not clear that such usage could have, or did filter down to workaday cowboys. A few contemporary descriptions of hats illustrate common features of cowboy and Mexican hat styles from the relevant period.

A report out of Fort Sumner, New Mexico in 1880 described the get-up of two travelers “decked out in the full war-paint of Texas cow-boys.” Their hats had hatbands, but not

fancy galon, just a rolled-up bandanna.

Either wears a whitish felt hat, vast of brim, and with a neatly-rolled red handkerchief tied around the minute portion of a crown; a blue woolen shirt, also surmounted in the region of the

neck with a red kerchief; calf skin leggins, trimmed with leather fringe and buttons adown the outer seams; spurs fiercely long in the rowel and given to jingling bravely; two belts, holdin in their loops 100 rounds of cartridges,

half for the revolver suspended from one of the belts and half for a repeating carbine.

The New York Times, July 25, 1880, page 10.

In an extensive interview first published in the New York Sun (and later republished in book form as Life and Adventures of a Cowboy), a famous cowboy named John H. Sullivan, who was better known by his stage name, Broncho John, described the functionality of the various items of a typical cowboy’s clothing and gear. He described the

use of hatbands on their hats, but made of leather, not fancy galon.

Take, for instance, the cowboy’s big-rimmed hat. The fact alone that it has been worn without changing fashion for generation after generation is enough to indicate that use not vanity,

dictated its origin. Until recent years, when the importance of these hats was recognized by hat manufactures and wool, felt, and fur were turned to account in making them, we made our own hats. . . . We wear leather bands

on all our hats, because cotton, woolen, or silk won’t wear and won’t keep the hats on.

Nowadays our hats are made in the East and made of the best fur of the best water animals. We can wash them or soak them in water for that matter, after they have been exposed to all kinds

of weather, and they hold their shape as if they were just out of the factory. They will do service for many years. The Stetson hat is the most commonly used in the West. They cost from $8 to $30. If made to order they

cost a great deal more. I have seen hats that cost $500.

The New York Sun, August 29, 1886, page 6.

An anecdote published in a popular illustrated magazine, about a man who brought a fancy Mexican hat onto a train in Texas, distinguished common Texan hats from fancier Mexican hats. The

Mexican hats, as described, were decorated with metallic trim consistent with the sorts of decorative ribbons called galon or galloon. Texan hats were apparently plainer and cheaper.

MEXICAN HATS.

A passenger in a coach from the West one night recently, writes a Fort Worth correspondent, when he boarded the train out on the plains, brought in and carefully deposited in the drawing-room

on one of the cushions, a $50 Mexican hat, stiff with silver thread embroidery and circled by a heavy silver cord. He was A. J. Adams, who, only twenty-eight years old, is able, out of the profits of his New Mexican ranch,

to indulge in the luxury of a $50 hat, but purely as a piece of interior decoration for an Eastern friend’s house. Sheriff Warne, of Mitchell County, who, with Millionaire Gregory, of Chicago, was admiring the hat,

said that General Valdes, when an exile from Mexico, had with him a hat that cost $600, and a California saddle that had cost $2,300. Both were heavily embroidered with gold and silver lace, and the general was very proud

of them. “It’s a common thing,” he added, “for these Texans to wear hats that cost from $15 to $25. In fact, a cowboy’s hat and saddle cost more than the whole of the rest of his outfit. The

boys get these big hats from the East, where they are manufactured, although they are never worn. A silk hat is as uncommon out here as one of these sombreros is on Broadway.

“These big hats are the best hats in the world. They are warm in Winter, and a shade in Summer. The Texans are very particular about the broad brims. They will touch nothing with

a brim narrower than three inches, and they want often a hat that is five and a half inches in width of brim. These hats last four or five years, and some cowmen have a superstition about them if they have good luck while

they own them, and after they have worn them a long while, they will send them on and have them cleaned and wear them several years longer. . . .”

“Why are Mexican hats so expensive?”

“They are made by hand. Unlike the Texan sombreros, they are made of wool carefully prepared, and each one of these costly hats represents several months’ labor. This hat, you

will see,” he added, as he rubbed his hand over the peak, “is as soft as a new-born baby’s cheeks. This silver thread is laid on by women, who are careful to mat it together. It gives the brim a curl, and

it keeps the tiny sugar-loaf in the centre stiff. This pattern is very simple, but you will see the cactus, the palm and the Mexican grasses picked out in gold and silver on many of the hats. The true Mexican will invest

his all in a fancy hat and clothe the rest of his body in dirty rags.”

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Volume 59, Number 1,529, January 10, 1885, page 343.

It may be true, as Arthur L. Campa said, that some people referred to some of their hats as “sombrero galon,” but it is not clear that such references would have been commonly

used among common working ranch hands, such that it might have spawned the expression, “ten-gallon hat,” to refer to over-sized western hats. Given the ubiquity of the use of galon or galloon in reference to decorative

trim on a wide variety of clothing and hat designs, it seems unlikely that the expression would develop specifically to describe a particular style of western or Mexican hat. It seems all the more unlikely, given the long

history of “x-gallon hat” to describe different styles of hats, long before it became used almost exclusively to refer to western-style cowboy hats.

The simple explanation is that the older expression gave way to a new meaning as hat styles changed.

“Tan Galan”

The earliest article floating the “tan galan” theory appeared separately, and nearly simultaneously, in two publications in 1985, the newsletter of an organization called National Image Inc. and a publication called, Hispanic Link. Without access to the full, original version, it is impossible to say who wrote the piece, but the excerpts available in snippet views via Google Books shows there is little or no evidence presented to support the claim.

The claim appears as one of a laundry list of Spanish or Mexican influences on the language of the American Southwest.

Thus the cowboy would say “Vamoose” (vamos; let’s go) “lasso” that “desperado” (deseperado; desperate one) and take him to the “hoosegow” (juzgado; court) and put him in the “calaboose” (calabozo; jail).

The cowboy would grow to like chile con carne and jalapenos and cooked his “barbeque” (barbacoa; from a Taino Indian word) out on the range.

Consider the origin of the ten gallon hat which is a direct copy of the charro’s (expert horsemen’s) tan galan (very decorative) sombrero. it has nothing to do with liquid capacity.

National Image Inc. Newsletter [October 1985]; Hispanic Link, Number 924, week of September 15, 1985.xxv

The claim would be more convincing if it included citations to Spanish-language references in which expert horsemen were said to be wearing tan galan sombreros. Sadly, no such citations were provided.

“Tan galan” is, in fact, an expression that can be found in 19th and early 20th century Spanish language texts. A search on the HathiTrust online archive, for publications printed in Mexico, before or during the year 1920, and with both the word string, “tan galan,” and the word “sombrero,” anywhere within the text, resulted in sixty-one raw “hits.” A random spot-check of somewhere between ten and twenty unique volumes in those results found precisely zero examples in which

tan galan appeared anywhere near the word sombrero, and in most cases (divined using admittedly limited Spanish abilities) seemed to refer to people, as opposed

to things, much less hats or sombreros. That is not to say that it could never happen, but there is no evidence, beyond the unsupported claim, that it did.

The suggestion that “ten-gallon” hat is a corruption of tan galan sombrero seems unlikely, given that it depends on the similarity between “tan” and “ten,” and that most of the early examples of “x-gallon”

hat are anything other than “ten” gallons.

Unless and until more (or any at all) evidence in support of such early usage is presented, I would caution against buying into the “tan galan” hat business.

But by all means, buy a ten-gallon hat.

i Philadelphia Times, March 5, 1885, page 4.

ii For more on the history and origin of the expression, “chestnut,” with reference to an old, stale joke or story, see “Horses,

Jokes and Bells - an Unfunny History of ‘Old Chestnut’ Jokes.” https://esnpc.blogspot.com/2019/01/horses-jokes-and-bells-unfunny-history.html

iii Owosso Times (Owosso, Michigan), January 16, 1891, page 1.

iv Wilkes-Barre Times Leader (Pennsylvania), February 14, 1911, page 8.

v Rockford Chronicle (Alabama), June 21, 1912, page 4.

vi Baltimore Evening Sun, October 13, 1914, page 1.

vii St. Joseph News-Press (Missouri), December 19, 1918, page 6.

viii The Evening Index (San Bernardino, California), February 24, 1919, page 9.

ix San Francisco Chronicle, March 10, 1919, page 15.

x Casper Star-Tribune (Wyoming), July 31, 1923, page 10.

xi Houston Post, July 10, 1923, page 1.

xii Muskogee Daily Phoenix and Times-Democrat, September 6, 1922, page 5.

xiii Anaconda Standard, May 23, 1923, page 9.

xiv Fort Worth Star-Telegram, October 16, 1923, page 4.

xv https://youtu.be/MpO9dB0aHsI?t=112

xvi For more silly and not-so-silly images of President Coolidge’s visit to South Dakota in 1927, see, “Presidential Visits

to South Dakota - Calvin Coolidge,” South Dakota Public Broadcasting, https://www.sdpb.org/blogs/images-of-the-past/presidential-visits-to-south-dakota-calvin-coolidge/

xvii H. L. Mencken, The American Language: Supplement I, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1945, page 313, footnote 3 (“An interesting discussion of ten-gallon hat, from the Spanish sombrero galon, by A. L. Campa, is

in American Speech, Oct., 1939, p. 201.”).

xviii Arthur L. Campa, Hispanic Culture in the Southwest, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1993 (brief biography

in the foreword, written by Richard L. Nostrand).

xix https://web.archive.org/web/20110817173554/http://harwoodartcenter.org/ss/harwood-girls-school-1925-197/

xx Albuquerque Journal, September 8, 1922, page 5.

xxi Albuquerque Journal, May 9, 1929, page 4.

xxii Albuquerque Journal, December 4, 1924, page 7.(“The business college team has in its

ranks five members of the Harwood team which was runner-up in the state tournament here in 1923. They are Madrid, Sisneros, Costalea and the Campa brothers, David and Arthur.”); Albuquerque Journal, February 15, 1925, page 4 (in a game between the ABC (Albuquerque Business College) and the “Lobo Pups” (in context, presumably the University of New Mexico freshman

squad), the Camp brothers of ABC combined for one point in a 24-22 loss).

xxiii Albuquerque Journal, June 1, 1926, page 5.

xxiv For a pic of Sir Charles Gordon Ramsey in his Admiral’s hat, see, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw209595/Sir-Charles-Gordon-Ramsey .

xxv The excerpt can be pieced together using snippet view of word searches in or around the text of interest on books.google.com.

The similarity of the text in the Hispanic Link version can be seen using a snippet view from a word search of the text on books.google.com.

The date of the Hispanic Link article can be seen on the snippet view of the search result. The date range of the National Image Inc. Newsletter version can be inferred and approximated using searches for years and months on a limited search available on the HathiTrust version of the reference.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)