|

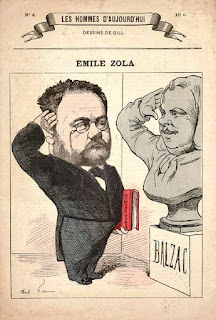

| The Evening World (New York), August 15, 1908, page 4. |

In golf, and

in life, a do-over is a “Mulligan” - and has been since at least

1936:

[T]he serious slangsleuth Paul Dickson reports the earliest

print citation to be an A.P. dispatch of May 5, 1936, crediting the use of mulligan

to Marvin McIntyre, an aide to F.D.R., which the reporter defined as

“links-ology for the second shot employed after the

previously dubbed shot.” The word was popularized in the coverage of

President Eisenhower’s golf outings.

William

Safire, “On Language,” The

New York Times Magazine, March 23, 2008.

No one

really knows the etymology for sure, but competing origin stories generally

credit the term to a Canadian golfer from Montreal, or a golf club locker room

attendant from New Jersey.

Sam Clements

recently discovered[i]

what seemed like, at first blush, a tantalizing clue:

If it is a bad ball, “off the

wicket,” he may take a “mulligan” at it and

knock it over the fence, “out of bounds” they call it.

The Colorado Springs Gazette, April 19,

1919, 12/3.

On closer inspection,

however, it does not seem to be a perfect match. The context and rules of cricket suggest that

to “take a ‘mulligan’” here, refers to taking a full, hard swing at the ball; not

to getting a second chance, as in golf.

It is

possible, I suppose, that this full-swing sense of “Mulligan” is a precursor to

the second-chance sense of “Mulligan.”

Did “Mulligan” originate from taking a second tee-shot; a full swing? But it may be just a “red herring”; any

similarity being just a coincidence. I

do not know and have not found any direct evidence of a connection.

[UPDATE 5/16/2017: See my new post: Hey Mulligan Man! -

But looking

into this newly rediscovered sense of “Mulligan” opened a window into some

forgotten aspects of early sports and pop-culture history; the mythical homerun king, “Swat Mulligan,” the

original “Sultan of Swat” (not Babe Ruth) and a possible etymology of “Mulligan Stew” (see my

earlier post - Irish

Stew, Irish Militias and Chowder – a History and Etymology of “Mulligan Stew”).

The swing-away

sense of taking a “mulligan” in cricket seems to be derived from the

name of greatest baseball hitter you’ve never heard of – “Swat” Mulligan. And, Babe Ruth was not the first “Sultan of

Swat” in baseball; and the original “Sultan of Swat” was not even a swatter of baseballs – he was from Pakistan – no news on whether he played cricket or not.

“Swat” Mulligan

“Swat”

Mulligan (or Milligan)[ii]

was a mythical baseball slugger who played for the “Poison Oaks” of the “Willow

Swamp League” during the earliest days of professional baseball. His forgotten exploits were rescued from the

trash-bin of history by the sportswriter Bozeman Bulger, who chronicled his Bunyan-esque

baseball accomplishments in a series of articles in the New York Evening World, beginning in about 1908.

One typical

article told how “Swat Milligan” foiled “Fahrenheit Flingspeed’s” egg-pitch;

only to be called out for being hit by his own batted ball. Flingspeed, of the “Fungo Falls Club,” planned

on getting the otherwise nearly invincible “Swat” Mulligan to swing and miss by

pitching a Killaloo’s egg to him.

Unluckily for him, Flingspeed was wearing a pair of pants he borrowed

from his bullpen-mate, “Harold Hangover.” In Hangover’s most recent outing, he

had used some magician’s flash powder to throw his “celebrated ‘firebug’ ball

causing Swat to set the woods on fire.”

Due to an unexpected chemical reaction between the egg and the residue

of the powder, the egg became hard and rubber-like in his pocket before it was

pitched. Mulligan hit the egg out of the

stadium; straight at city hall:

But due to the “extra-ordinary

resiliency of the ball (egg) . . . instead of going into the window it struck

the swaying flagstaff on top of the hall with a mighty crash. As if shot from a Mauser rifle the ball

bounded back to the park and struck Swat squarely in the back as he was making

his ninth run [around the bases].”

The Evening World, July 1, 1908, page

12.

In another

tale, an injured “Swat” Mulligan pulled a “Kirk Gibson”; limping

onto the field after missing two games (he had been laid up due to his fondness

for drinking baseball bat varnish), and hit a homerun after “getting

the goat” of a Russian pitcher by telling him to, “go back to the mines” in

Russian. Heady stuff!

|

| The Evening World (New York), August 15, 1908, page 4. |

The only

pitcher who ever really got the best of “Swat” was Cy Young; although it must

have been late in Mulligan’s career (Cy Young became a professional in 1889 and

entered the major leagues in 1890).

|

| The Evening World, July 1, 1908, page 12. |

“Swat’s” sudden,

post-career fame led to a stage play based on his life and a doll (action

figures, I guess) in his likeness.

|

| The Evening Star (Washington DC), February 12, 1911, part 2. |

|

| Tacoma Times (Washington), July 7, 1911, page 6. |

In 1915, the New York Yankees tried to lure “Swat” out of retirement to coach the Yankees:

|

| The Seattle Star (Washington), January 13, 1915, page 9. |

And his son,

“Swat Mulligan, Jr.”, also played some professional ball:

|

| The Evening World (New York), June 14, 1919, page 9. |

As a result

of “Swat” Mulligan’s reputation as a great baseball slugger, other

sportswriters would sometimes refer to strong hitters in baseball and golf as

the “Swat Mulligan” of their respective team or sport:

|

| The Evening World (New York), August 22, 1919, page 2. |

|

| The Evening World (New York), June 13, 1919, page 22. |

| The Evening World (New York), July 10, 1917, page 10. |

In 1920, even

the immortal Babe Ruth was said to display his “Swat Mulligan Stuff” at the

Annandale course in Pasadena, California:

|

| The Evening World (New York), March 13, 1920, page 8. |

It seems

likely that the word, “mulligan,” as used to describe a batsman in cricket, was

a reference to “Swat” Mulligan and his prodigious talent.

The “Sultan of Swat”

Babe Ruth, a real “Swat Mulligan” of the diamond and the links, was also known as

the “Sultan of Swat,” a title he bore regularly beginning in the 1920 season,

the year after he set a new major league homerun record (29) in 1919, his last

season with the Boston Red Sox.

But “Babe,”

who is still revered as THE “Sultan of Swat,” was not the first. In August of 1920, for example, Grantland

Rice (who is responsible for popularizing, “it’s not whether you

win or lose, it’s how you play the game”) referred to Babe Ruth as:

. . . the new Sultan of Swat

. . . [iii]

Earlier that

year, Rice had even praised a different “Sultan of Swat” and tried to predict a

successor – without including Ruth in the discussion:

[Ty] Cobb has

only a year or two to go as the Sultan of Swat,

and when he begins to skid the battle to take his place will be a merry one, with

Sisler favored, as Collins, Jackson and Veach are no longer debutantes.[iv]

Just one

month earlier, Grantland Rice referred to Pat Moran, the manager of

the Cincinnati Reds as, “the Red Sultan of Swat”[v]; two years earlier (1917), he had dubbed Honus Wager, “Honus – Honus the Hittite – Sultan of Swat”.[vi]

And even then, the expression

had already been around for a few years, even if it did not appear regularly or

often in print. As early as 1911, a

sportswriter from Detroit debated:

Who is the best hitter in the

world? Here is a question that base ball fans throughout the territory in which

the national game is played never tire of arguing. Any one of a dozen sluggers can bring forward

thousands of admirers who will talk until they are black in the face to prove

that their man is the one and original Sultan of Swat.[vii]

[(candidates included Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, Larry Lajoie, Tris Speaker, Honus

Wagner and Sherwood Magee)]

The Real Sultan of Swat

In 2009, Foreign Policy Magazine online published an article entitled, “The Sultan of Swat,” about the dangerous Taliban leader who held sway over the Swat Valley at the time. Although I do not know the motivation for the headline, I would not be surprised if the editors had intended the headline to be a clever reference to Babe Ruth's moniker. If so, the expression had come full-circle since the "Babe's" nickname was derived, in the first instance, from an actual title of a former ruler of the region - the “Sultan of Swat”.

[T]he ruler of Swat, called himself Sultan.

Edward E. Oliver (illustrated by J. L. Kipling), Across the Border: or, Pathan and Biloch, London, Chapman and Hall, 1890, page 218.

Before the Yusufzai Afghans settled in the Peshawar valley, Hashtgnar was held by the Shalmanis, a Tajik race, subjects of the Sultan of Swat.

The Imperial Gazatteer of India, Volume 13,

Oxford, 1908, page 60.

Swat is a mountainous district in Pakistan once known as the “Switzerland of Pakistan”; but which is now better known as a former Taliban stronghold and location of some of the fiercest fighting in the Afghan War and the Global War on Terrorism. As of 2015, however, peace had returned.

As noted by

Greg Kemnitz, writing

on Answers.com:

"Swat" [(in the

nickname, “Sultan of Swat”)] is also a double meaning:

"Swat" is also the name of an actual district in Pakistan . . . . At various times in its history, Swat's leaders were called Sultans. So, there were "real" Sultans of Swat in history, and doubtless a sportswriter with some sense of history and geography gave The Babe this enduring nickname.

"Swat" is also the name of an actual district in Pakistan . . . . At various times in its history, Swat's leaders were called Sultans. So, there were "real" Sultans of Swat in history, and doubtless a sportswriter with some sense of history and geography gave The Babe this enduring nickname.

While it is

true that sportswriters eventually gave the title to various baseball sluggers,

including most enduringly to Babe Ruth, other writers in the early 1900s used

the real title, “Sultan of Swat,” as a humorous, shorthand title for generic, "exotic" characters.

In 1904, for example, a writer for the New York Sun was so happy fishing that he would not trade places with an Eastern potentate:

For the gentle spring days have come, the balmy blissful days when the sun is just right and the earth seems to have reached teh very limit, and as we sit here, with our float bobbing up and down on the rippling water and the bait only half gone, we would not change places with the Sultan of Swat and the King of Knuck both rolled into one and riding around in a 100 horse-power automobile over a special track paved with prostrate cops and bill collectors.[viii]

In 1906, a poem in the New York Sun described how theatrical press agents create new sensations:

“The Milk Bath Artist Has Seen His Day,”

. . .

The marrying girls of the sextette bunch,

. . .

The marrying girls of the sextette bunch,

The girl who jilted a millionaire,

The girl who, ‘tis said, one time

took lunch

With the Sultan of

Swat (on a girlish dare)[ix]

In 1912, writing about the love life of a famous actress from Cincinnati who affected a French persona:

Gertrude’s Parisian accent and

shoulder-shrug won her instant recognition.

An Indian rajah – we failed to catch the gentleman’s name, but we are

sure it was not the Sultan of Swat – visiting

New York, was so enchanted with her beauty, and especially her dazzling,

flashing teeth, that, when she declined to join his harem, he presented her

with his favorite anklet of burnished gold to match Gertrude’s burnished gold

hair . . . .[x]

In a 1914

article about how American diplomats avoid the ostentatious accessories favored

by their European counterparts:

Swank! . . .Yankee swank!

Your ambassador to the Court of

St. James must wear his dress suit without trimmings. For him decorations of any kind are sternly

forbidden. No ribbons or medals may

ornament his breast. Knee breeches and

silk stockings are not for him. It is

the same with the American minister plenipotentiary to the Sultan of Swat [(although the rest of the story was

about an American diplomat to Zanzibar – which is nowhere near Swat)].

The use of “Sultan

of Swat” appears to be a melding of an actual title and the idiomatic use of the title with yet another baseball title - the “King of Swat.”

The “King of Swat”

Long before

anyone was the “Sultan of Swat” in baseball, the “King of Swat” (which dates to

as early as 1901[xi])

reigned supreme. At various times,

Honus

Wager was the “King of Swat” . . .

|

| South Bend News-Times (Indiana), December 25, 1913, page 8. |

“Nap” Lajoie

was the “King of Swat” . . .

|

| Tacoma Times (Washington), June 9, 1913, page 2. |

Ty

Cob was the King of Swat . . .

|

| Tacoma Times (Washington), February 20, 1918, page 6. |

. . . and

“Shoeless” Joe Jackson was the “King of Swat.”

|

| El Paso Herald (Texas), June 28, 1913, comic section page 6. |

Eventually, Babe

Ruth was crowned the “King of Swat”:

|

| Richmond Times Dispatch (Virginia), November 6, 1921, page 62. |

The earliest

examples of Ruth as the “King of Swat” pre-date the earliest examples of him as

the “Sultan of Swat that I could find. He may even have been better known as the

“King of Swat” at least early in his career. Searches in databases of pre-1923 newspaper for

[“king of swat” and “babe ruth”] yield about twice as many “hits” as searches for [“sultan

of swat” and “babe ruth”].

But for some reason, the “Sultan of Swat” was more enduring . . . perhaps it was the ridiculous crown (King Vitamin anyone?).

[i] American

Dialect Society’s e-mail discussion list archive, June 17, 20:10:25 EDT 2016.

[ii]

“Swat’s” last name was originally “Milligan,” but over time, he was frequently

referred to as “Mulligan,” even by writers in his own paper, and sometimes in

headlines above articles in which the name was spelled, “Milligan.”

[iii] The Washington Herald (Washington DC),

August 19, 1920, page 9.

[iv] The New York Tribune, January 2, 1920,

page 10.

[v] The New York Tribune, December 26, 1919,

page 10.

[vi] The Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennylvania),

February 24, 1917, page 14.

[vii] The Ogdensburg Journal (Ogdensburg, New

York), March 28, 1911, page 5 (referencing an article from the Detroit Free Press).

[viii]

The Topeka State Journal, April 29, 1904, page 8 (reprint from the New York Sun).

[ix] The New York Sun, November 4, 1906,

page 33.

[x] The Seattle Star (Washington), August

29, 1912, page 4.

[xi] The St. Louis Republic, November 1,

1901, page 4 (“[Patsy] Donovan has by no means given up hope of retaining the

King of Swat [(Jesse Burkett)].”)

[Note: Edited November 8, 2018 to add one early (1890) reference to the actual Sultan of the Swat Valley, and minor edits for clarity.]

[Note: Edited November 8, 2018 to add one early (1890) reference to the actual Sultan of the Swat Valley, and minor edits for clarity.]