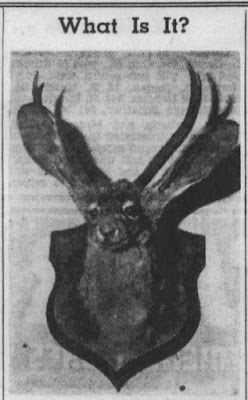

What is it?

A “jackalope.”

Indigenous to the

wide-open spaces in souvenir shops of the American West, “jackalopes” can also

be found as invasive species on tchotchke shelves and man-cave walls

worldwide.

A portmanteau of “jackrabbit” and

“antelope,” a jackalope is a stuffed jackrabbit mounted with deer or antelope

antlers. But when this photograph of a

gift shipped from Kern County California to Pennsylvania was published in 1942,

there was no accepted single word to describe it.

Despite occasional reports of such

animals in the wild in newspapers across the country since at least the 1890s,

they were generally referred to simply as “antlered jackrabbits,” “horned

jackrabbits,” or similarly bland, descriptive phrases. Early attempts (1930) to coin a more

expressive name, “boop-oop-o-doopdeer” or “whatizzitt,” never quite caught

on.

The earliest accounts of horned or

antlered jackrabbits were likely legitimate sightings of actual jackrabbits

suffering from wart-like, viral growths, now known as the Shope papilloma virus. Readers, however, frequently misunderstood

the reports, believing them to be a genuine new or unknown species, or

dismissed as the drunken hallucinations of hunters on a bender, or outright

fabrications. The absence of

photographic or physical evidence and rarity of the condition prolonged the

confusion.

But by the early 1930s, creative

taxidermists had taken matters into their own hand, stuffing the void with

natural-looking fakes. While it may be

impossible to determine with certainty who made the first one, the Herrick

brothers of Douglas, Wyoming generally get credit. The brothers, they say, made their first one in

1939 (or 1934 or 1932, depending on the source). But the evidence is thin, sometimes

contradictory, and the date hard to pin down.

Other sources suggest similar fakes were

made elsewhere even earlier. It’s possible

that different people, in different places and at different times,

independently mounted antlers on jackrabbits to mimic the horned or antlered

jackrabbits regularly described in press reports over many decades. The earliest-known contemporaneous report of

an antlered jackrabbit hunting trophy on display was at a ticket office of the

Northern Pacific Railroad in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1932. And reports made decades after the fact

suggest they may have existed during the 1920s, and perhaps as early as 1912.

But it took a Presidential whistle-stop

tour through Wyoming in 1950, and a concerted effort of civic self-promotion by

the Chamber of Commerce of Douglas, Wyoming to finally give the unforgettable

creature an unforgettable name – the “jackalope,” and give it the national

attention it deserves. Later attempts to coin alternate names, “antelabbit”

or “sarabideer” (saber-toothed rabbit-deer), did not make any inroads. “Jackalope” was here to stay.

Douglas, Wyoming was not the first

western town to use fake-taxidermy to promote the town. Whitefish, Montana did something nearly

identical with “fur-bearing fish” in the mid-1920s, right down to a pair of taxidermists

who made the first examples. A widely publicized

faux-fish feud between Whitefish and the upstart Salida, Colorado, who later

claimed to be the home of the “fur-bearing fish,” kept the fish in the

limelight during the 1940s, which would have given Douglas ample opportunity to

become familiar with the concept.

And if Douglas, Wyoming was inspired

by Whitefish, Montana, Whitefish Montana was likely inspired by nearby Glacier

National Park and the Great Northern Railway that brought visitors to the

park. Beginning in 1911, the year after

it was established, the park and railway brought attention to the park with

tall-tales of fabulous creatures like the “Wimpuss” and fur-bearing “polar

trout,” and fantastic geologic features like a subterranean connection between

its lakes and the Arctic Ocean, and a “Bourbon Spring,” in the middle of a

field of mint, perfect for mint juleps chilled with glacial ice. Images of the “Wimpuss” were distributed in

photo-albums distributed throughout the park, and a fake-taxidermy specimen of

a “Wimpuss” hung on the wall of the park’s hotel lobby.

A Natural History of Jackrabbits

with Horns

Reports of jackrabbits with horns or

antlers first appeared in great numbers in Kansas, Texas and other states of

the Great Plains and American Southwest in the 1890s.

Bill Spencer killed two horned jack-rabbits the other

day. One of them had four horns, two on

each side of its head. The other had but

one horn which proceeded from near the end of its nose, like the horn of a

one-horned rhinoceros. The horns were of

perfect structure and about three inches in length. We only regret that they could not have been

captured alive.

Ness County News (Ness City, Kansas), February 13, 1892, page 4.

Herbert Cook shot the other day in the timber on the Sioux

river a cotton-tail rabbit which was a decided curiosity.

It had antlers like a deer.

The main horns were about an inch long and on each a prong had started,

one side being considerably larger than the other. The antlers were located near the base of the

ear.

Star Tribune

(Minneapolis, Minnesota), January 30, 1900, page 5.

Although not fully understood at the

time, many (if not most) of these reports were likely genuine sightings of

jackrabbits with horny growths caused by a virus; growths which, if they grow

from the top of the head, sometimes look a lot like antlers or horns, although

generally more irregular and asymmetrical.

Many of the descriptions are consistent with the viral growths.

|

| Arizona Republic (Phoenix, Arizona), April 27, 1927, page 17. |

Although eyewitnesses may have

understood that the horny growths were not really like horns or antlers,

readers were left to their imagination.

With frequent repetition and recirculation, and generally without

photographic support, the reports morphed into something slightly more

fantastic, and ultimately unbelievable.

As a result, the familiar reports of “horned” or “antlered” jackrabbits

would frequently be dismissed as a joke or as the drunken rambling of hunters

off on a bender.

By the time that fourteen-mile-lake in Barton county gets

filled with water Kansas will begin to grow sea searpent stories, too. They will be appreciated. The horned jackrabbit story is becoming sadly

frayed.

Dodge City Globe (Dodge City, Kansas), February 2, 1899, page 2.

A Jackrabbit with five horns has been seen out in Pratt

county, Kan. And Kansas, as everybody

knows, is a prohibition state.

Edgerton Journal (Edgerton, Kansas), March 22, 1907, page 2.

“I think I’ll go in for hunting, my dear,” said Mr.

Sudden-Wealth. “I hear there’s excellent

rabbit shooting in these parts.”

“Do so by all means.

Hunting is aristocratic. And some

antlers will look well in the front hall.

Courier-Journal

(Louisville, Kentucky), January 27, 1919, page 6.

In 1930, a hunter’s mistake and

perhaps some sloppy editing of the initial report of the event, prompted

reports of a rabbit with antlers in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, with calls

to hunt it down, stuff it and put it on display.

[D]id you know we had a new kind of animal in the upper

peninsula? Hunting it will further complicate the dangers of the deer hunting

season. Won’t be at all surprised to

have the AP devote a column to this boop-oop-o-doopdeer or whatizzit. The first mention of the queer animal

appeared in an editorial in a newspaper of the peninsula. Here is the quotation:

“In his excitement, he had mistaken her for a rabbit and

pulled the trigger – not waiting to see the antlers.”

If you see a rabbit with antlers running around in the woods,

don’t you do a thing but hike to the nearest telephone and call up this office

so we can send out a hunting party to bring in the boop-oop-o-doopdeer for the

conservation department’s wild-animals-we-have-known exhibit at the Marquette

county fair next year.

The Ironwood Times (Ironwood, Michigan), November 28, 1930, page 8.

An innocent reading of the report is

that the rabbit hunter accidentally shot a deer, shooting before making sure it

was a rabbit – “not waiting to see the antlers [which would have shown it was a

deer].” A more ridiculous reading of the passage suggests a deer hunter

accidentally shot a rabbit without ensuring it was a deer – “not waiting to see

the antlers [which would have shown it was a deer].” In either case, the report is ambiguous,

giving rise to the inference that the hunter believed rabbits had antlers or

had seen rabbits with antlers.

Another newspaper published what

appears to be an alternate version of the Michigan story, only this time in

Minnesota and garbled by several layers of miscommunication as in a game of

“telephone.”

Rabbits with deer antlers have been seen by Minnesota hunters

who, if their liquid ammunition holds out, will be chased up trees by squirrels

with giraffe necks and elephant trunks.

South Bend Tribune (Indiana), December 8, 1931, page 6.

An Unnatural History of “Jackalopes”

With decades of reported sightings,

perhaps it was inevitable that someone, somewhere, sometime would create a

lifelike model. It’s not entirely who

did it first or where, but there are several candidates. Conventional wisdom holds that the Herrick

Brothers of Douglas, Wyoming did it in 1939, or 1934 or 1932, but there are

other candidates.

A rare, early photograph of something

like a jackalope, said to have been captured and mounted near San Benito,

Texas, was reprinted in newspapers across the country in late-1912 and into 1913.

|

| Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pennsylvania), December 15, 1912, page 7. |

Although it’s possible that this was

an actual virus-inflicted jackrabbit, nearly four decades later, a man from

Canada claimed to have faked a photograph and story of an antlered jackrabbit

that “got around all over America” years earlier. The report said it had happened “25 years

ago,” which would date it to 1921. But

the only such viral image an exhaustive search for early jackalopes has

uncovered is the one pictured above, from 1912.

If his story is true, and if the date given was just a general

recollection off by a few years, John Reid of Princeton, Ontario may have made the

earliest known “jackalope.”

John Reid, of Princeton (Ontario), is hale and hearty at 87

years, because he has been sustained during the years by a pretty good sense of

humor. Out of the village comes the

story of how he whittled down and sharpened a pair of deer spikes and stuck

them into the head of a big jack rabbit he shot 25 years ago. He suspended the rabbit well enough for a

good picture. How that story got around

all over America! An antlered jack rabbit, forsooth!

Ottawa Journal

(Ontario), February 13, 1946, page 8.

Another antlered jackrabbit

reportedly hung on the wall of a restaurant in Livingston, Montana as early as

1928. Again, the dates might be off, and

the animal might actually have been diseased, but then again, it might refer to

an early example of a stuffed “jackalope.”

An antlered rabbit, snapped by amateur photographers for two

decades, is in the possession of a thief.

An unknown collector stole the mounted animal from a local

restaurant. The owner swears the rabbit,

with horns like deer antlers, was shot by a woodsman in the Hellroaring country

after its horns snagged in brush.

The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana), July 24, 1948, page 2.

Given that “jackalopes” are so

unbelievable, it seems fitting that the earliest, contemporaneous reference to

a “jackalope” hunting trophy on display was submitted as a local entry to a

national Ripley’s Believe it or Not contest.

Rabbit With Antlers

Caroline Heft . . . makes note of something thousands of

people must have seen: “In April, 1932, there was on display in the window of

the N. P. [(Northern Pacific)] railroad ticket office, St. Paul, a snow shoe

rabbit with beautiful little antlers about six inches long, each antler had two

prongs. A clerk in the office informed

me this freak had been captured out in Idaho.”

The Minneapolis Star Tribune, May 13, 1932, page 8.

The year 1932 is a critical date in

the history of the “Jackalope.” It’s the

jumping off point for determining whether the Herrick brothers, Douglas and

Ralph, could have invented the “jackalope” in 1932, as claimed.

Discounting the earlier claims that

were made decades later, is it possible that the Herricks made a “jackalope” in

1932 that inspired the one in the St. Paul railroad ticket office in April

1932? By the Herrick’s own admission, it

couldn’t be the same “jackalope,” because they claim to have sold their first

“jackalope” to the LaBonte Hotel in Douglas.

Let’s look at the facts. In April 1932, the older of the two Herrick

brothers, Douglas, was 11 years old, three months shy of his twelfth birthday

in July.[i] His younger brother, Ralph, would most likely

have been 8 years old, or at most a month or two past his ninth birthday.[ii]

In 1977, the Wall Street Journal and the New

York Times separately reported the year of the Herricks’ first “jackalope”

as 1934. But a more local newspaper, The Casper Star-Tribune, located fifty-five

miles down I-25 from Douglas, reported the year as 1939 on numerous occasions, beginning

as early as 1992. And when the Wyoming

state legislature considered naming the “jackalope” that state’s “official

mythical animal” in 2005 (the bill died in committee), they listed 1939 as the year

of origin.

It was only Ralph Herrick who “insisted”

after his brother’s death in 2003 that it happened in 1932.[iii] On balance, the evidence suggests they were likely

not the first, but it’s not impossible.

It is as possible as an 11-year-old and an 8-year-old making a fake

hunting trophy sometime during the first three months of 1932. But that’s not to say they didn’t create

their own “jackalope” independently, as others seem to have done elsewhere.

And if the Herricks made the first

one in Douglas, Wyoming, they likely played a leading role in popularizing the “jackalope,”

perhaps inspiring the town of Douglas to usher their “jackalopes” into national

prominence in the wake of a Presidential visit to the region by Harry S. Truman

in 1950.

The Chamber of Commerce of Douglas,

Wyoming might also have been inspired by the Chamber of Commerce of Whitefish,

Montana, who for decades had famously promoted their town with a fake-taxidermy

of fur-bearing fish, which had coincidentally been made by a different set of taxidermist

brothers.

And Whitefish, Montana, in turn, was

likely inspired by nearby Glacier National Park and the Great Northern Railway,

who had both promoted tourism to the park with tall-tales of “wimpusses” and “polar

trout” and their own of fake-taxidermy.

Fur-Bearing Fish

The earliest fur-bearing fish

reference in Montana is a play on the arguably ambiguous wording of a proposed

wildlife management bill for the protection of “fur-bearing animals and fish.”

The bill introduced in the house by Boardman of Deer Lodge,

providing for the better protection of fur-bearing animals and fish, relates to

a subject that may very properly receive legislative attention. During the past years the destruction has

been immense, and in consequence of this wanton slaughter fur-bearing fish are

already almost unknown in the sparkling brooks of Montana. But proper legislative measures can easily

correct this abuse, and then the toothsome “pike,” the broad shouldered

“sheephead” and estimable “sucker” will cherish beneath their shaggy sides,

deep in their heart of hearts, a well spring of gratitude for their noble

protectors in the Montana legislature.

Butte Miner

(Butte, Montana), February 1, 1911, page 4.

The joke may have been a

one-off. There was no claim (real or

humorous) that they actually existed, and there is no evidence of any local

fur-bearing fish legends or traditions there until decades later, when separate,

unrelated reports “polar trout” were combined to form the legend of the

fur-bearing fish of Iceberg Lake.

In June of 1913, newspapers across

the country published the astonishing claim that so-called “polar trout,”

previously known to have existed only in the Arctic Ocean, had been found in

Iceberg Lake in America’s newest National Park.

There was only one possible explanation (cue eye-roll) – a subterranean

connection between the park and the Arctic Ocean.

|

| Oakland Tribune (California), June 1, 1913, page 40. |

A few months later, newspapers across

the country published a fake-news item about the return of a purported explorer

named John Bunker, who had recently returned from Greenland with stories and

actual specimens furry “polar trout,” but it was likely pure bunk.

Polar trout, the only fur-bearing fish known to natural

history, is the latest contribution of the arctic regions, according to John

Bunker of Northwood Center, N. H., known as the Isaac Walton of that state, who

today reached Boston from a two months’ exploring trip in Greenland. He brought photographs and actual specimens

of the strange fish, which he has called the polar trout.

. . . The skin is covered with a fine brownish fur,

resembling the texture of moleskin. This

fur is slightly spotted with white, as is a young seal in the spring. Bunker says this fact first led him to call the

curiosity a polar trout.

Inter-Ocean

(Chicago, Illinois), October 20, 1913, page 5.

Six months later, a travel writer

appears to have conflated the two stories into a new rumor – fur-bearing fish,

like the ones previously reported from Greenland, could also be found in Iceberg

Lake. The discovery was attributed to “Hoke

Smith,” but was it merely a hoax?

Iceberg Lake is the habitat of the polar trout discovered by

Hoke Smith, who says they have fur instead of scales.

Norton Courier

(Norton, Kansas), March 19, 1914, page 7.

The report came from a full-page

travelogue and photo essay of Glacier National Park that appeared in dozens of

newspapers across the country. The

story, “Among the Glaciers,” was written by a man named Frederick William

Pickard, “expert fisherman,” Vice President of DuPont, and author of several serious fishing guides,[iv]

not by someone generally prone to flights of fancy. The comment appeared as a casual aside,

tucked in between descriptions of the new automobile road and the Glacier Park

Hotel, and with no apparent skepticism or curiosity.

It is not clear whether Pickard

conflated the two stories on purpose, or whether the stories had already been

combined by others, and he was just repeating something he had heard in the

park. But he almost certainly did not

swallow the story hook-line-and-sinker.

Anyone visiting the park in 1914 would have been regaled with all sorts

of silly stories about the “natural history” of the park, most of them coming

(or attributed to) the same man.

The “polar trout” hoax of 1913 was

only one of several unbelievably strange “discoveries” in the park attributed

to wordsmith and press agent, “Hoke Smith,” a hoax-smith extraordinaire, even

if by any other name.[v]

Three years before the first fur-bearing

fish stories from the park, he was credited with discovering the “Wimpuss”

(good eating in-season, but only if killed properly – by making them laugh

themselves to death) and the “Bourbon Springs” (formed by acres of corn trapped

underground after an earthquake in 2435 BC, distilled underground by a hot

water geyser, and aged four thousand years, before bubbling to the surface in

the middle of field of mint – makes for good mint juleps chilled with glacial

ice).

Park management, the hotel owner and

the Great Northern Railway, which brought visitors to the park, all embraced

these freshly minted legends as elements of their marketing plans.

The Glacier Hotel hosted a “grass

dance” in October 1911, “one of the features being the discovery of ‘Bourbon

spring’ in the center mint bed. The

spring was surrounded by small pine trees and mint juleps cooled by glacier ice

were served. While it was not possible

to capture a live wampus, the party are all in favor of coming again for this

purpose.”[vi]

Picture books placed prominently in

the “lounging tents of all the camps” for viewing by the guests included “an

article on the ‘Wimpus’” and a “clever sketch by a Chicago writer and has

flattering reference to Hoke Smith, one of the Great Northern’s publicity men.”[vii] Presumably, the “clever sketch” was the one

that appeared alongside Richard Henry Little’s original “Wimpuss” story in the Chicago Tribune.

|

| Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1911, page 6. |

The hotel also kept a fake-taxidermy,

stuffed “Wimpuss” on the wall above the newsstand in the lobby.

The walls are adorned with trophies of the chase . . . as

well as . . . the only existing specimen of the far-famed “wimpus” of Glacier

National Park.

. . . Would you believe there are wimpus believers! A model of this creature occupies a

conspicuous place over the newsstand in Glacier Park Hotel. Close observation and careful study of th

external appearance of the animal show it to be a mixture of fish, monkey,

reptile, cat, spider, and bat.

Mathilde Edith Holtz, Glacier national Park, Its Trails and

Treasures, New York, George H. Doran Company, 1917, pages 34, 170.

|

| Purple Parrot, Northwestern University, Volume 4, Number 7, April 1924, page 5. |

While the “Wimpuss” and “Bourbon

Springs” received occasional mentions in the press over the following decade, the

furry “polar trout” faded into relative obscurity. That would change in 1925.

Fire Chief Collins has returned from the convention of

Montana firemen, held at Whitefish last week, enthusiastic over the reception

tendered to the visitors, and with a fish story that would make Isaac Walton

reach for a gun. Irvin S. Cobb, famous

humorist, who is vacationing in Glacier National park, was seated next to Chief

Collins at a banquet where the insult to the finny tribe was perpetuated and is

now preparing to tell the world of the “fur-bearing fish.”

. . .

The toastmaster announced that after much labor an entirely

new specimen of the underwater wiggler had been produced and brought from under

the table a large glass jar containing a fish about a foot long, completely

covered with, what was beyond a doubt, a wonderful coat of fur. It was explained that the fish could live

only on an island and that the citizens of Whitefish had built an island in

Whitefish lake to accommodate the new species.

The one difficulty that could not be overcome was the fact that the

fur-bearing fish had a peculiar digestive system and could exist on nothing but

ice worms.

According to Chief Collings, it was more than a quarter of an

hour before the guests, including Cobb, were wise to the fact that a clever

taxidermist had slipped a speckled trout into a gopher’s hide, and added that

Cobb then and there started to “dope out a story.”

The Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana), June 30, 1925, page 8.

The initial report did not disclose the

name of the “discoverer,” but one year later, a Montana newspaper gave credit

to the Chief Dispatcher of the Whitefish office of the Great Northern Railway.

Decades later however (as was the

case with the jackalope), two taxidermist brothers claimed to have invented the

fur-bearing fish.

It lived in iceberg lake in the Montana Rockies. It had a fur coat instead of scales to

protect it from the burning cold of the lake.

It hunted fat ice worms for dinner, and the men who fished for it had to

heat their hooks first. It often

exploded, once landed, just from the sudden change in temperature.

That fish was one of the minor national preoccupations of its

time. The new streaked across the

country, and scientists gave out statements. . . .

The fur-bearing trout was though up by two brothers,

taxidermists in Whitefish – C. H. and S. A. Karstetter, who still practice

their art here.[viii]

It was a local gag for a while. The late R. E. Marble of Whitefish took a

picture of the oddity.

The Billings Gazette (Billings, Montana), July 4, 1942, page 7.

|

| R. E. Marble’s postcard of Hicken’s Fur Bearing Trout. Examples can still be found in online auctions from time to time. This example bore a postmark dated 1928. |

In 1930, one local businessman sent

what might have been an identical copy of this same postcard to a friend in

Baltimore.

The water in this lake is so cold that nature has taken care

of her own by providing the fish with a thick coat of fur, the letter

said. In fact, the water is so cold, Mr.

Jackson writes, that it is beyond the freezing point.

The Evening Sun

(Baltimore, Maryland), November 26, 1930, page 6.

And in addition to the postcards,

locals occasionally presented various stuffed-shirts with their own stuffed

“fur-bearing fish.”

Whitefish, May 17. – (Special) – Roy. N. Arnold, city water

commissioner . . . had the honor of

presenting a mounted specimen of the renowned fur-bearing fish to the president

of the National Waterworks association who was in attendance at the

meeting.

The Missoulian

(Missoula, Montana), May 18, 1938, page 5.

|

| James E. Murray, United State Senator from Montana, showing off his “mounted furry fish.” Great Falls Tribune, July 4, 1942, page 3. |

Another article clarified the origin

of the fish, splitting the difference, giving credit to everyone involved for

their respective contributions, including to the Whitefish Chamber of Commerce.

Whitefish, Jan. 25. (Special) – The famous fur-bearing fish,

invented by the late James Hicken, Great Northern dispatcher, built by

Karstetter Bros., photographed by the late R. E. Marble and publicized by the

Whitefish Chamber of Commerce, is the basis for the fourth annual contest in

business letter writing sponsored by the Business

Education World, a professional journal for teachers of business subjects.

Great Falls Tribune (Great Falls, Montana), January 26, 1941, page 7.

But as “famous” as Whitefish had become

as the home of the “fur-bearing fish,” there were other rivals to the title.

In 1937, a purported catch in

Missouri briefly caught the public’s eye.

The fish resembles a trout in every respect except that it

has a rich coat of fur completely covering its body in longitudinal stripes,

brown and gray-yellow, much on the order of a chipmunk. The stripes run from snout to tail.

Orlando Evening Star (Orlando, Florida), October 29, 1937, page 9.

William LaVarre debunked the Missouri

fish in his syndicated column, “Seeing’s Believing!” where he published “photographic

proof” sent to him by the purported discoverer.

The fur, he said, was from a chipmunk.

|

| The Indianapolis Star (Indiana), January 9, 1938, Gravure Section, page 3. |

About one year later, similar stories

popped up about “fur-bearing fish” in the Arkansas River in Colorado. It was no ordinary fish. And the man responsible was no ordinary

faker; he was a convicted pyramid scheme fraudster, recently pardoned by

President Roosevelt and reinventing himself as publicity agent for the Chamber

of Commerce of Salida, Colorado.

SALIDA, Colo. – Wilbur B. Foshay, who in 1928, headed a

22-million-dollar utilities empire, is working these days for the people who

got him out of jail. And doing a good job, too.

As the super-salesman manager of this citys Chamber of

Commerce . . . the 57-year-old Foshay is one of Salida’s most admired citizens.

. . .

The Dothan Eagle (Dothan, Alabama), February 28, 1939, page 10.

Wilbur Foshay’s last name is familiar

to residents of Minneapolis, where the Foshay Tower is still a prominent

feature of the skyline. But whereas his

tower still stands, his fortunes sank. His

crimes, related to financial schemes that crashed with the stock market in 1929,

were precisely the sorts of financial dealings that helped bring about the

crash.

Others lost their shirts, but Foshay

lost his freedom. He was sentenced to 15

years in prison, serving only three years, after Roosevelt reduced his sentence

by five years, with another two off for good behavior.

Foshay’s first big success was his

popular “Follow the Hearts to Salid” campaign.

|

“Follow the Hearts to Salida,” image courtesy of the

|

His second big success involved a

different type of bathing beauty, one dressed for cold weather.

Tourists and tenderfeet from the effete East have been

regaled frequently with the tale of fur-bearing trout that were indigenous to

the waters of the Arkansas River.

Recently, a resident of Pratt, Kan., wrote to city officials

here urgently requesting proof of the story of the unusual fish.

The letter was turned over to Wilbur b. Foshay, secretary of

the Salida Chamber of Commerce.

Without definitely committing himself – in a letter – as to

the truth of the existence of pelted piscatorial prizes in Arkansas, Foshay

simply mailed the inquirer a photograph of a fur-bearing trout.

Oldtimers in the region aver these fabled fish were numerous

hereabouts at one time, but that they are rapidly nearing extinction.

Orlando Sentinel (Florida), December 4, 1938, page 11.

Efforts to prove or disprove the

rumor were frustrated by law – according to Foshay.

Furry fin-flippers, Foshay said in a letter . . ., can be

caught only in January – when fishing is not permitted in Colorado streams.

Nevada State Journal, January 10, 1939, page 1.

Years later, similar restrictions on

Douglas, Wyoming’s “Jackalope Hunting License” prevented would-be jackalope

hunters from bagging their own in the wild; the license restricts hunting to

June 31, between sunrise and sunset.

Not everyone took the claims of

fur-bearing fish in Salida seriously.

“Fur-bearing Fish Found in Colorado.” – Headline.

Old stuff, according to Elmer Twitchell, the famous

piscatorial expert. “I found fur-bearing

fish years ago,” he declares. “In fact,

I bred ‘em for the pelts. Know what

killed the business?”

“No,” we replied.

“Moth-fish,” replied Elmer.

The Record (Hackensack,

New Jersey), January 26, 1939, page 8.

The head of the bureau of fisheries

aquarium in Washington DC, on the other hand, waded into the debate with

perhaps too much seriousness, throwing a big wet rag over the story.

“This is the season for fur-bearing fish, and naturally so,”

said the fisheries official. “The fur,

however, isn’t fur, but fungus.”

The Evening Times (Sayre, Pennsylvania), January 13, 1939, page 7.

The head of the bureau of fisheries

was not the only person to take the stories seriously. Dorothy A. Johnson, a

former resident of Whitefish, Montana then living in New York City and working

as a freelance writer and editor of for a publishing company,[ix]

“blew her top” when first reading about them.

Defending the good name of Whitefish as the authentic habitat

of the authentic fish. I challenged the Salida

man, Wilbur Foshay to a duel “on the second Tuesday of any week in 1989” and

named as my seconds (without consulting them) Fiorello LaGuardia, mayor of New

York, and Joe Louis.

Great Falls Tribune (Montana), April 13, 1952, page 15.

She also encouraged the secretary of

the Whitefish Chamber of Commerce to engage in an extended letter-writing war

with Foshay (with carbon copies to Johnson).

The effort was successful, extracting a retraction from Foshay and

establishing a brief truce.

Everything was fine until she (as

editor of a business education magazine) arranged for the fur-bearing fish of

Whitefish, Montana to be featured as the subject of a national letter-writing

contest for students. Shortly afterward,

Foshay planted Salida fur-bearing fish stories in two magazines, This Week and World Digest; she countered with a mention in the Saturday Evening Post, after which they

“retired to neutral corners and growled at each other.”

In 1945, when Johnson

was the editor of a women’s magazine called, The Woman, she published an article about the whole affair

entitled, “The Feud of the Fur-Bearing Fish.”

Years later, when she recounted the whole

affair for the Great Falls Tribune,

she included a photo of her own fur-bearing fish alongside her collection of

pistols, perhaps sending Foshay one last, subliminal message about their feud.

|

| Great Falls Tribune (Montana), April 13, 1952, page 2. |

As compelling as the fish feud may

have been, it was not her best work. At

least three of her stories were adapted as screenplays for three classic

Westerns, The Man Who Shot Liberty

Valance, starring Jimmy Stewart, The

Hanging Tree, starring Gary Cooper, and A

Man Called Horse, starring Richard Harris.

In 1913, a press agent for the Great

Northern Railroad reported “polar trout” in Iceberg Lake, trout later said to

be fur-bearing. In 1925, two

taxidermists and a dispatcher for the Great Northern Railway created a physical

model of a “fur-bearing fish.” In 1928,

passersby saw an antlered jackrabbit in the window of a ticket agent for the

Northern Pacific Railway in St. Paul, Minnesota.

It seems appropriate, then, that a

railroad would play a role making “jackalope” the standard terminology and

establishing Douglas, Wyoming as the undisputed Jackalope Capital of the

World. But it wasn’t a press agent,

ticket agent or dispatcher who did it. It

was a whistle-stop tour by President Harry S. Truman.

“Jackalopes” – Douglas, Wyoming

In early 1950, officials in two

western states encouraged President Truman to attend the dedication of two

separate dams. The Chamber of Commerce

of Casper, Wyoming invited him to attend the dedication of the nearby Kortes

Dam, then scheduled to coincide with the June meeting of the Missouri Basin

Inter-Agency Committee in Casper the following June.[x] The Bureau of Reclamation hoped to have

former First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt and President Truman at the dedication of

the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State.[xi]

The President accepted both

invitations, announcing a “non-political” trip to Grand Coulee Dam, with

“whistle stops” along the way,[xii]

including a stop at the Burlington Station in Casper, with a brief excursion to

the dedication of Kortes Dam, now moved up to May to coincide with the

President’s visit.[xiii]

The Chamber of Commerce of Douglas,

Wyoming, which lies about 55 miles east of Casper, on the same Burlington rail

line that would carry the President to his whistle-stop in Casper, sensed an

opportunity for some national exposure. Their

own hoax-smiths took a page out of “Hoke Smith’s” book, getting the word out to

politicians, journalists, hangers-on, or anyone else coming to Wyoming, that

they might find something interesting to see in Douglas.

Their press-releases followed the

familiar pattern established by Whitefish, Montana; civic pride, photographs, fake-taxidermy,

and an elaborate “natural history” of a mythical animal. Whether coined for the purpose, or repeating

a designation already in common use locally, the story may also be the earliest

known example of the word, “jackalope,” in print.

. . . “The first white man to see this singular specimen was

a trapper named Roy Ball in 1829. When

he told of it later he was promptly denounced as a liar.

“An odd trait of the jackalope is its ability to imitate the

human voice. Cowboys singing to their

herds at night have been startled to hear their lonesome melodies often

repeated faithfully from some nearby hillside.

The phantom echo comes from the throat of some jackalope.

“They sing only on dark nights just before a

thunderstorm. Stories that they

sometimes get together and sing in chorus are discounted by those who know

their traits best.”

The News

(Paterson, New Jersey), March 1, 1950, page 21.

The plan seemed to work, with

numerous mentions in newspapers across the country, and an editorial in The Christian Science Monitor (May 15,

1950), then one of the leading news magazines in the country, which prompted a

new spate of news stories around the country.

|

| Casper Tribune-Herald, May 21, 1950, page 6. |

The Christian Science Monitor gave Truman’s “non-political” trip a political spin, imagining

another kind of mixed political animal, the “donkephant” – something that today

would more likely be called a RINO.

This is the general region through which President Truman has

passed recently on his “nonpolitical” speaking trip. We are waiting now for reports of political

naturalists to see whether they report the presence of any donkephants in the

area – that is, Republicans who were half-persuaded by folksy eloquence of the

Democratic chief executive from the party of the elephant to that of the

donkey.

Star-Tribune

(Casper, Wyoming), May 21, 1950, page 6 (from an editorial in The Christian Science Monitor).

Although the level of attention to “jackalopes,”

and the name itself, were new in 1950, stuffed trophies of jackrabbits with

antlers had been known in Wyoming and throughout the West for years, aside from

the several examples already discussed.

A woman in Wisconsin showed off her

postcard of one from her vacation in Wyoming in 1936.

Martha Cleveland, Mazomanie, has spent several summers on the

Horned Jackrabbit ranch in Montana, and if you don’t believe that there is such

a thing as a horned jackrabbit, she can show you the postal cards which the

ranch manager keeps on hand for the guests to send out to doubting friends

which show a photograph of a big jackrabbit with a pair of fine antlers

sprouting out of his head just in front of his tall flopping ears. The camera never lies, they say, but there is

something very odd about that rabbit.

The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), July 26, 1936, page 3.

A young man in Montana stuffed and

mounted his own jackrabbit with antlers in 1940.

Wayne Woodard of Roy, a young farmer boy who has been doing

taxidermy work during his spare moments, is attracting attention . . . .

He displayed a jackrabbit head, with very small deer horns so

cleverly placed that hunters stood in wonder when they first saw it, thinking

they were looking at a new species of deer.

Great Falls Tribune (Great Falls, Montana), June 9, 1940, Sunday Magazine, page 7.

Bert Clancy, a “great nimrod” and

Assistant District Attorney for Santa Fe, New Mexico, displayed one in his

office in 1944.

The mounted head of a jackrabbit with horns, four inches

long, hangs from the wall of his office at the country courthouse. “Seeing is believing,” said Clancy. “I’m not under oath and I refuse to be

cross-examined. There’s a New Mexico

jackrabbit.”

The Santa Fe New Mexican, October 17, 1944, page 8.

And a furniture

dealer in Indiana had one on display in his store in 1946.

A great lover of the outdoor life,

Mr. Gable has made frequent trips into the choice hunting spots in Quebec,

Colorado and Wyoming. . . . His trophies, all on display in the west room of

the store, include four moose heads, several deer heads, antlers, a sailfish,

and a large sea turtle. Not to be

forgotten, however, and most treasured of all his trophies is a rare species of

jackrabbit – with antlers!

The Muncie Star (Indiana), June 2, 1946, page 2.

“Antlered jackrabbits” had even

garnered some notice in the press in central Wyoming, just down the road from

Douglas, a few years earlier when Harold King, the President of the Natrona

County Game and Fish Association, put one on display in Casper, Wyoming in 1946. Comments in the article seem to suggest that jackrabbits

with antlers were not yet generally well known, even in central Wyoming, and

that they were not yet universally known as “jackalopes.”

Even an expert hunter cannot always believe his eyes, as the

above picture indicates. Many a Casper

sportsman looked twice when the “antlered jackrabbit” appeared in a store

window and caused considerable consternation among sportsmen, sportswomen and

children.

Tribune-Herald

(Casper, Wyoming), March 3, 1946, Annual Wyoming Edition Supplement, page 18.

Harold King also laid out an

elaborate origin story, different from the one sent out by the Douglas Chamber

of Commerce a few years later. King said

that the antlers were “an example of how Mother Nature tries to even up the

odds among her animals,” and that the modification was of recent vintage,

having developed in response to unique conditions following a cricket invasion in

1938.

The antlers provided a place for the crickets to sit besides

on the long ears. It seems that before

the crickets became so thick on rabbits’ ears that they weighted them down and

the rabbit couldn’t hear the coyotes sneaking up on them.

Tribune-Herald

(Casper, Wyoming), March 3, 1946, Annual Wyoming Edition Supplement, page 18.

The hard-news journalists from the

East who followed President Truman’s train through Douglas and Casper in 1950

somehow missed this discrepancy. But luckily,

a local reporter cleared up the confusion a year or so later. The specimen Harold King displayed in Casper

was no “jackalope,” it was a “jackrabbit with antlers,” a separate species, “possibly

a cousin, 43 and ¾ times removed from the jackalope” in Douglas.[xiv]

The same article also claimed that

King’s “jackrabbit with antlers” had been on display for “15 years,” dating it

to about 1936, a time when Douglas and Ralph Herrick would have been about 15

and 11 years old, respectively.

Today, Douglas, Wyoming is the

undisputed “Home of the Jackalopes.” Even if they weren’t first, it is a

well-earned honor. Not only did they put

“jackalopes” on the map, “jackalopes” put them on the map (with an assist from

a Presidential visit). The center of

town is called “Jackalope Square,” where you can see one of the world’s finest jackalope

sculptures (although

Wall Drug in Wall, South Dakota, might have something to say about

that), and they are the home of an annual “Jackalope Days” festival.

The Chamber of Commerce in Van Horn, Texas tried something similar with something called the “Antelabbit,” but it never caught on.

|

| Daily Mountain Eagle (Jasper, Alabama), December 18, 1958, page 16. |

Epilogue

Although the Herrick brothers may not

have made the original and first “jackalope” ever, they did make a lot of them,

and they played an important role in “jackalope” history, which would make

their first “jackalope” an important artifact.

Sadly, however, it is missing. It

suffered the same fate as the Karstetter brothers’ original, permanently mounted

“fur-bearing fish” from Whitefish, Montana – it was stolen.

The “original mounted fur-bearing fish” has been stolen from

Frenchy’s Chinese café here, L. G. (Frenchy) DeVall, the owner values the fish

at $100. Its value as the first of its

kind cannot be estimated, he said. The

existence of fur-bearing fish has been a subject of controversy for 30 years,

since the first one ever discovered was presented, to the author, Irvin S. Cobb

by Jim Hicken of Whitefish when both men were initiated into the Blackfeet

Indian tribe in ceremonies here. That fish was ffresh and, for course,

spoiled. Karstetter Brothers, local

taxidermists, have a patent on the process of preparing the fur-bearing fish

and only 12 have been mounted. The one

stolen from Mr. DeVall was the first prepared for permanent display.

Missoulian

(Missoula, Montana), June 17, 1951, page 11.

The Herrick’s first “jackalope” was

stolen in September 1977, shortly after attention was focused on it by an

article in the Wall Street Journal in

August.

[T]he original jackalope was sold 43 years ago to the late

[Roy] Ball, who put it on display in his La Bonte Hotel here. This jackalope was stolen from the hotel in

September and the culprit remains at large.

“Where the Deer and the Jackalope

Play,” The New York Times, November

26, 1977, page 26.

All of which just goes to show you .

. .

Hair/Hare today, gone

tomorrow.

|

| Detail from the back of a matchbook cover from the LaBonte Hotel. |

Links to

Further reading:

Update: Edited September 20, 2023, to add photographs of the Douglas, Wyoming Jacaklope statue in Jackalope Square.

[i] On

the occasion of his death in 2003, Douglas Herrick’s hometown obituary gave his

birth date as July 8, 1920. Casper

Star-Tribune (Casper, Wyoming), January 6, 2003, page 4.

[ii] A man named Ralph Herrick was 62 years old in February 1985 when he was sentenced to one

year in jail and five years of “stringent probation,” after pleading guilty to

fondling a 10-year-old girl the previous summer. When officers came to arrest him in January

1985, he held-off the police during a nine-hour standoff, threatening to blow

himself up with a fake explosive. Casper

Star-Tribune (Casper, Wyoming), February 21, 1985, page B1. Given the location, low population density, and similarity of name and age, it seems likely it is the same man as the taxidermist named "Ralph Herrick."

[iii] “Douglas

Herrick, 82, Dies; Father of West’s Jackalope,” New York Times, January 19, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/01/19/us/douglas-herrick-82-dies-father-of-west-s-jackalope.html

[iv] Frederick

William Pickard was originally from Portland, Maine, attended Bowdoin College

(Class of 1894) and became a Vice President of DuPont. The citation

for an honorary doctorate conferred on him by his alma mater describes him as an “expert fisherman.” He is the author of Trout Fishing in Ireland, Sixteen

British Trout Rivers, and Trout

Fishing in New Zealand in Wartime.

[v]

The name “Hoke Smith” raised the hoax antenna of at least one amateur

historian. The name had been used for

decades in punning reference to hoaxes, most commonly in association with

stories involving an actual person named “Hoke Smith,” a former Secretary of

the Interior and Governor of Georgia who served as a U. S. Senator from Georgia

from 1911-1920. Various references to

the press-agent or newspaperman named “Hoke Smith” who is credited with

devising several tall-tales about Glacier National Park, generally refer to him

as being from Minneapolis or St. Paul, or as a newspaperman from Chicago. Coincidentally, there was, in fact, a

journalist from Minneapolis named Roy “Hoke”

Smith, who later wrote for the Chicago

Evening Post. It is possible that

the seemingly fake name “Hoke Smith” for a wordsmith who devises hoaxes (“hoax-smith),

was actually his name, or at least the nickname he used when making up

fake-news stories.

[vi] Butte Miner (Butte, Montana), October 3,

1911, page 5.

[vii] Semi-Weekly Spokesman-Review (Spokane,

Washington), September 15, 1912, Magazine Section, page 1.

[viii]

In September 1912, the Karstetter brothers moved their taxidermy business to

Whitefish, Montana from their old home in what is now the ghost town of Java,

Montana (Whitefish Pilot, September

5, 1912, page 3). They stayed in

business as taxidermists and hunting guides for decades. In 1929, they stuffed and mounted perhaps

their second-most famous animal, a parachute-jumping chimpanzee that died in

1928 after his chute failed to open in a show at Great Falls, Montana. (The Independent-Record (Helena, Montana),

Janaury 20, 1929, page 10).

[ix] “Witty,

Gritty Taleteller: A Life of Dorothy M. Johnson,” Brian D’Ambrosio,

DistlinglyMontana.com, October 4, 2017 ( http://distinctlymontana.com/node/39920

).

[x] Casper Tribune-Herald, January 20, 1950,

page 4.

[xi] The Semi-Weekly Spokesman-Review

(Spokane, Washington), February 8, 1950, page 16.

[xii] Daily Herald (Provo, Utah), February 24, 1950, page 16.

[xiii]

Spokane Chronicle (Spokane,

Washington), March 9, 1950, page 1.

[xiv] Casper Herald-Tribune, September 14,

1951, page 9.