Language Tortured. - Why is the inscription generally found in confectioners’ shops of ‘Water Ices and Ice Creams,” like a person attacked with hydrophobia - because when ‘Water I sees, I screams.’

The Sporting Magazine, Volume 5, N. S., Number 27, December 1819, page 134.

Grammar. - “James, decline ice cream.”

“Yes sir; I scream, thou screamest, he screams.”

Monmouth Inquirer (Freehold, New Jersey), June 3, 1847, page 1.

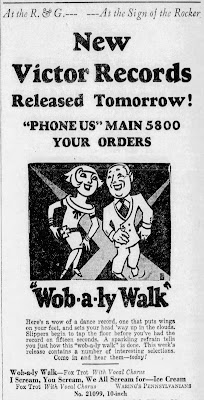

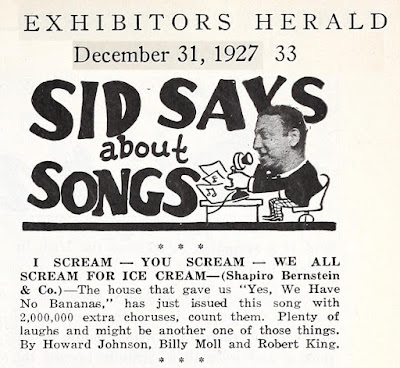

In 1927, the songwriter Billy Moll wrote the popular hit, “I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice Cream,” first released as the B-side of Waring’s Pennsylvanians’ record, with Wob-a-ly Walk on the A-side.

|

Evansville Press (Evansville, Indiana), December 29, 1927, page 2. |

Billy Moll’s song may have cemented the phrase in American pop-culture, but he does not deserve the credit (blame?) for coining the expression. It had been around in identical form since at least 1905.

|

Stevens Point Journal (Stevens Point, Wisconsin), May 13, 1905, page 4. |

|

Lebanon Daily News (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), June 21, 1905, page 6. |

And variants of the expression, with various combinations and permutations of pronouns, had been used in ice cream marketing since at least the 1840s.

The earliest example I found of the pun in an advertisement for ice cream appeared in 1846, in a small item with twice as many puns as sentences.

“I scream.” - A perfect bijou of an ice-creamery was opened by Mr. J. H. Cornwell, at No. 136 Fulton street last evening, treating his friends in the freest and most hospitable, though very cool manner. He gave a regular “house warming” though somewhat paradoxically with ice cream, and other delicacies of the season.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 16, 1846, page 2.

A slightly more high-brow pun appeared the following year, anticipating, perhaps, the now-familiar “I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream.”

Grammar. - “James, decline ice cream.”

“Yes sir; I scream, thou screamest, he screams.”

“Go up head.”

“Fourth class in Grammar, attention! How is Grammar divided?”

“In Ornothology, Etimography, Swinetax, and Mahogany.”

“School’s dismissed.”

Monmouth Inquirer (Freehold, New Jersey), June 3, 1847, page 1.

|

York Gazette (York, Pennsylvania), June 12, 1849, page 3. |

|

Daily American Telegraph (Washington DC), April 26, 1851, page 2. |

The Weekly Caucasian (Lexington, Missouri), July 19, 1873, page 3.

|

Messenger and Examiner (Owensboro, Kentucky), July 3, 1878, page 3. |

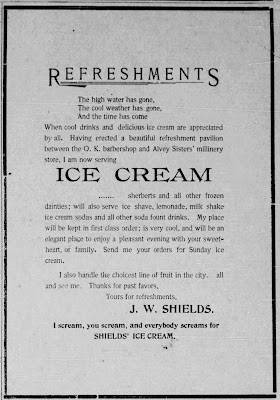

- I Scream, - You Scream, - We Both Scream!! Because Dickman keeps the best Ice Cream to be had in town. Large dish for 10 cents.

Chautauqua Democrat (Sedan, Kansas), Juen 12, 1884, page 3.

|

McPherson Republican (McPherson, Kansas), May 5, 1881, page 3. |

To the Dudes. - Take your best girl to Blodgetts’ Ice Cream Parlor and get a dish of ice cream that will curl the hair, sweeten the breath and put a smile on your girls face that will not wear off during ice cream season. . . .

I scream, you scream and everybody screams that Blodgetts’ ice cream takes the cake, which is furnished at 10 cents per dish.

The Frankfort Sentinel (Frankfort, Kansas), May 21, 1886, page 3.

|

| The Tampa Tribune (Florida), April 18, 1896, page 1. |

|

The Democrat Argus (Caruthersville, Missouri), May 6, 1897, page 5. |

|

The Vicksburg American (Vicksburg, Mississippi), April 18, 1903, page 4. |

Cameron County Press (Emporium, Pennsylvania), August 11, 1904, page 1.

Ice Cream/Rabies

The Ice cream/I scream pun predates its earliest known use in advertising. Jokes and humorous anecdotes based on punning “I scream” with “Ice cream” date to at least 1819. Surprisingly, perhaps, the earliest example is a joke about hydrophobia (rabies).

Language Tortured. - Why is the inscription generally found in confectioners’ shops of ‘Water Ices and Ice Creams,” like a person attacked with hydrophobia - because when ‘Water I sees, I screams.’

The Sporting Magazine, Volume 5, N. S., Number 27, December 1819, page 134.

The joke was still in circulation six years later, as evidenced by this article intended to shame comedians who steal old jokes.

Theodore Hook’s second-hand Jokes. - Some time since we showed that a new joke of the John Bull was a very old one, as a correspondent of ours had played off the Di-do-dum pun some years before it appeared in the John Bull as span new. We have now to take a similar liberty with Mr. Theodore Hook, who has lately been making free with another specimen of bathos, which appeared in the Kaleidoscope several years ago. We do not pretend to say that it was original with us, but we do say that it did not originate with Mr. Hook. We always gave credit to one of our correspondents for this chef d’oevre in the bathos, which we here repeat: -

“Why is a pastry-cook’s shop-window lke a man in hydrophobia?” - “Because its motto is, Water, ices, and ice-creams” - (water, I sees, and I screams.”) Oh! oh! oh! - Edits. Mercury.

Liverpool Mercury (Liverpool, England), June 24, 1825, page 6.

The joke was floating around the United States a decade later.

Excellent. - The following is too good to be lost, especially when such a pun is perpetrated in the dog days; therefore we secure this gem of wit in the Ledger.

“Water, Ices, and Ice Creams.” - Why are these words, which we sometimes see in a confectioner’s sign, like the ungrammaticla exclamation of a person in hydrophobia? D’ye give it up? It is because they sound like “Water I sees, and I screams!” - N. Y. Sun.

Public Ledger (Philadelphia), July 16, 1836, page 2.

Ice Cream/Confusion

A second line of humorous anecdotes played on the confusion an ice cream street vendor might create when hawking their wares screaming “ice cream.”

3 o’clock. The patrician dinner hour. The mart was abandoned - myself departing with the rest, to save appearances. Met a strong-lunged fellow with a large tin bucket, shouting with hideous gesticulations, “I scream!” - Found he had ice-cream for sale.

Long-Island Star (Brooklyn), March 3, 1825, page 1.i

A lengthier (and perhaps less plausible) anecdote out of New York City made a similar point a few years later. Whether it actually happened this way or not, it shows that the Ice cream/I scream pun was still making the rounds.

I-I-I-Screaming. At the corner of Fuloton and Nassau streets sits a black fellow, with an enormous mouth and strong lungs, bawling ice-cream, loud enough to be heard a mile. His voice is peculiarly harsh and shrill, and he pronounces the words so, that one would suppose, instead of notifying for sale the cool and dulcet article which composes his stock in trade, he was screaming merely for screaming’s sake. Thus -

“I-I-I-scream! I-I-I scream!”

This peculiarity of screaming ice-cream leads to some very amusing observations of the passers by, as well as to some little trouble and vexation to the African screamer.

Confound you! I think you do scream,” said Charley McQuiz, as he stopped to see what sort of a throat it could be that sent forth such sounds

“I-I-I scream! I-I-I scream!” repeated the negro.

“Well, rot you! don’t I know it?” said Charley, “I heard you scream a mile off.”

“Buy some I-scream, Massa?”

“Buy it! no, you fool - do you think I’ll buy your screaming, when I can get more than I want it for nothing!”

“No, Massa; I neber sells I-scream for nossing. Can’t possibly ‘ford it.”

“Can’t afford it! why, it costs you nothing except breath - and that’s as cheap as shingle nails at three-pence a yard.”

“Yes, masssa, but consider, besides de breff, dere is so much money to pay for stock in trade - so much money for rent - ”

. . .

[H]ere’s a shilling for you to buy a new breath in case your present one should ever fail - of which I fear there is no prospect.”

“Tankee you, massa, - hopes for your cons’ant custom. I-I-I scream! I-I-I- ”

“Confound you! don’t scream any more, if you don’t want my fist down your throat.”

“O Loddy, massa! I no want him in my troat.”

“No want him in your troat! then keep your troat shut, till I get out of hearing - don’t scream again till I’m a mile off.”

“I see you furder first, and den I wont.”

With this assurance, Charley went on, and Tony kept his mouth shut until he had doubled the first corner, when he began repeating as loud as ever - “I-I-I scream! I-I-I scream!” - and so he continues screaming every evening. N. Y. Constellation.

Philadelphia Album and Ladies Literary Port Folio, Volume 5, Number 32, August 6, 1831, page 256.ii

In 1839, boys in Baltimore annoyed a street vendor by hollering, “I scream” when the vendor yelled “Ice cream!” He preferred selling oysters for precisely that reason. But, ironically, it was his sale of oysters that gave rise to a misunderstanding which led to some undeserved bad press about his supposedly shady business practice of issuing (Flintstone-like) oyster shells as “shinplasters” (privately issued money), in lieu of legal tender.

The Baltimore Sun had published a rumor that “a distinguished gentleman of color named Moses, who hawks about

‘charming’ oysters, is about establishing an office where he will redeem such oyster shells as he gives in lieu of change.” Offended by the allegation, Moses showed up at their offices to set the record straight. The Sun printed his explanation and their retraction the next day.

Q. Well, Moses, why have you honored me with a visit, this morning?

A. Why, sir, I hearn they got me in the Sun.

Q. Got you in the Sun! What have you been doing to attract its notice? Whistling too loud - selling bad oyster,s, or issuing shinplasters?

A. That’s it, master, that’s it! them gent’men says, I isshers ohster shells for shin plaisters, tain’t no such thing - please God, I never gin a shell for money to any body in my life - I glad to git some one to take away the shells for nothin - I hearn lawyers eat the oshter and pass the shells to their clients - but nobody else ain’t going to cheat in that way. You axed me if I been whisling too loud - I whisles nothing but sams, hims [(psalms, hymns)] and sich like - and hollers ‘lilly, lilly, lilly, Le-la,’ ‘le-la, poor old Moses - poor old feller!’ . . . I likes to holler for oshters better than ice cream - caze the boys plagues me, and hollers, ‘I scream,’ - and some of the fellers kin holler ‘lilly, lilly, lilly,’ as well a most as I kin - but they hain’t got the voice, poor little things.

Q. Well, Moses, why did you come to me?

A. Caso I want you, if you please young master, to tell them gent’men of the Sun, that I think myself above issing shin plaisters, or any sich cheating work, and if they wants good oshters I can sell ‘em as good as they can find in town - and I thank ‘em to let my character alone.

With many apologies to the respectable colored gentleman, we publish the above in order to show that he is above bad company. He has our admiration of his uprightness and our wishes for his success. May he live a thousand years.

The Baltimore Sun, November 30, 1839, page 1.

I Scream/Pain

At about the same time, the ice cream/I scream pun served as the punchline for a joke in which the “scream” of the joke represented pain, not an inducement to the pleasures of ice cream.

One such story illustrated the dangers of showing off one’s children for company. A woman who had taught her children French from a young age, tries to impress her friends by having her son demonstrates his ability to pronounce French words correctly. After several successes, she promises a reward if he gets just one more right. He struggles, and winds up revealing embarassing details about his mother’s early-morning drinking habits, which gets him “I scream” instead of “ice cream.”

“Now Frank, say bouquet, and you shall have some ice cream. “

Frank thus encouraged, commenced - ‘boo,’ ‘boo,’ but getting no farther, the mother continued.

“That’s right so far. Vulgar people always say bo, but boo what, Frank?”

Upon a second trial the child kept ‘boo-booing’ until his mother, fearful that he would e set down for a booby, again came to the rescue with ‘come Frank, you say it. You certainly have not forgot what do I put in the glass every morning?”

“Oh, I know now - why b- b- brandy, mother!”

Frank got I scream, for ice cream, and was sent away to get up his French. He went out boo boo-booing to another tune.

The Mississippi Free Trader (Natchez, Mississippi), June 26, 1847, page 2.

The same pain/pleasure version of the pun appeared in small item about women in Mississippi who were able to make ice cream after collecting hailstones following a spring storm.

Several ladies were able to secure the hailstones in sufficient quantities to give their friends an unexpected treat of ice-cream in the evening. Those who were out in the storm enjoyed the luxury of I scream, with very little trouble.

The Port Gibson Herald and Correspondent, March 30, 1849, page 2.

Billy Moll

Wilbur (sometimes reported as Wilbert or William) “Billy” Moll, who wrote “I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice Cream,” was born and raised in Madison, Wisconsin, the son of Frank Moll, a carpenter for the University of Wisconsin. He was still an infant in 1904, when his mother died at the age thirty-one. His father and his step-mother (the former Mrs. Woerpel) lived for many decades in a home that still stands at 1915 University Avenue in Madison, Wisconsin.iii

Billy was not the first prominent person in his family. His first-cousin, Keckie Moll, played quarterback for the University of Wisconsin’s varsity football team in 1908, 1909 and 1911, leading the Badgers to a 13-3-2 record, with no more than one loss in each of his three seasons at the helm. His uncle William “Billy” Moll was a woodworker and contractor, credited with creating the woodwork for the Wisconsin State Capitol.

Billy’s first songwriting success appears to have been “The Memphis Maybe Man,” published in 1924, when he would have been about twenty years old. The song was recorded by (among others) “Cook” and his Dreamland Orchestra.

His next big hit seems to have been “Six Feet of Papa,” written with Art Sizemore in 1926, and recorded by Annette Hanshaw on Pathe Actuelle Records.

“Ice Cream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice Cream” was a big hit in 1927, with notable recordings by Harry Reser’s Syncopators and Waring’s Pennsylvanians.

Moll wrote more than 500 songs in Madison (including “I Scream”) before moving to New York City in August 1929, where he was offered a full-time position with the music publishing company, Shapiro, Bernstein and Co. Before leaving town, he married Loretta Radecke, of Stoughton, Wisconsin.

Once in New York, his employers put him to work writing theme songs for “talkie” movies; “Lil,” for the film, For the Love of Lil, “Seargeant Flagg and Sergeant Quirt,” for the film, “Cock-Eyed World,” and “Atta Boy,” for Howdy Broadway.

In 1930, they tasked his with writing the lyrics for a Broadway musical entitled, Have a Good Time, Jonica, scored by Joseph Meyer, who also wrote “California Here I Come.” Jonica had a short run at the National Theater in Washington DC in mid-March, 1930, before opening at the Craig Theater on Broadway, on April 7.

The “amusing and often ribald production”iv was about a young, innocent who leaves a convent in Buffalo to serve as maid-of-honor at a friend’s wedding in New York City. Before she leaves, she’s given a revolver named “Benjamin Franklin” to protect her from the big, bad world. Along the way, she is suspected of murder, stumbles into the groom’s bachelor party, meets his best friend (an artist who specialized in painting nudes), and joins her friend on the altar as the second bride in a double-wedding.

The songs received some positive reviews.

The production has some exceptionally good music - notably “I Want Someone” and “A MIllion Good Reasons.

Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey), May 12, 1930, page 9.

But not everyone agreed.

No colossal feature stands out in a humdrum of songs and music that takes to the old beaten path and follows it right along through to the finish of a tame love story.

Times Union (Brooklyn), April 8, 1930, page 13.

“Jonica” folded after five weeks.

Later that year, Bing Crosby introduced the song that would be one of Moll’s best known songs, “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams (and Dream Your Troubles Away),” singing it on the California Melodies program on KHJ radio station in Los Angeles on November 5, 1930.v Crosby’s recording of the song in 1931 helped launch his solo career.

One of Moll’s other big hits, “I Want a Little Girl,” was also released in 1930. Ray Charles recorded a bluesy version, Eric Clapton a funky version, and Nat King Cole a swingin’ version of the song.

Billy Moll’s career eventually slowed down, and he moved back to his wife’s hometown of Stoughton, Wisconsin. But he remained active, publishing his last big hit, “At the Close of a Long, Long Day,” first recorded by Jimmy Wakely in 1951.

He died in Stoughton in 1968.

The songs and the expression he helped popularize, “I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream,” live on.

i Barry Popik, “I scream for ice cream,” The Big Apple Online Etymological Dictionary, April 24, 2009 (“April 1962, New-York Historical Society Quarterly, “New York City in 1825: A Newly Discovered Description” by Bayrd Still, pg. 2: (Quoting a newspaper of 1825—ed.) Met a strong-lunged fellow with a large tin bucket, shouting with hideous gesticulations, “I scream!” Found he had ice-cream for sale.”).

ii Also reprinted in, Vermont Patriot and State Gazette (Montpelier, Vermont), August 22, 1831; Newbern Spectator (New Bern, North Carolina), September 23, 1831, page 4.

iii According to Zillow.com, the house was built in 1899.

iv Evening Star (Washington DC), March 26, 1930, page 22.

v Los Angeles Evening Express, November 5, 1930, page 9.

No comments:

Post a Comment